21

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Use invention to understand problems and develop solutions. (SLO 2, 3, 4; GEO 1, 2)

- Organize a proposal by drafting the major sections separately. (SLO 1, 2, 4; GEO 1, 2)

- Choose a style that will be persuasive to your readers. (SLO 1, 4, 5; GEO 1, 2)

- Create a design that will make your proposal attractive and accessible. (SLO 4; GEO 1)

Student Example

Inventing Your Proposal’s Content

Inquiring: Defining the Problem

State your proposal’s topic and purpose.

The purpose of this proposal is to show how college students can help fight global climate change.

Narrow your topic and purpose.

The purpose of this proposal is to show how our campus can significantly reduce its greenhouse gas emissions, which are partly responsible for global climate change.

Find your angle.

We believe attempts to conserve energy offer a good start toward cutting greenhouse emissions, but these efforts will only take us part of the way.The only way to fully eliminate greenhouse gas emissions here on campus is to develop new sources of clean, renewable energy.

Inquiring: Analyzing the Problem

Identify the major and minor causes of the problem.

Keep asking, “What has changed?”

Analyze the major and minor causes.

Researching: Gathering Information and Sources

Your concept map will give you a good start, but you also need to do some solid research on your topic. When doing research, collect information from a variety of online, print, and empirical sources. You can then “triangulate” your research by drawing material from online, print, and empirical sources.

Electronic Sources

Choose some keywords from your concept map, and use Internet search engines to gather background information on your topic. Pay special attention to Web sites that identify the causes of the problem you are exploring. Also, look for documentaries, podcasts, or broadcasts on your subject. You might find these kinds of sources on YouTube, Hulu, or the Web sites of television networks.

Print Sources

For proposals, your best print sources will usually be newspapers and magazine articles, because most proposals are written about current or local problems. You can run keyword searches in newspaper and magazine archives on the Internet, or you can use the Readers’ Guide at your library to locate magazine sources. On your library’s Web site, you can use research indexes to find articles in academic journals. Or your local government or university may have published reports that directly address the problem you want to solve.

Empirical Sources

Set up interviews, do field observations, or survey people to gather empirical evidence that supports or challenges your online and print sources. Someone on your campus, perhaps a professor or a staff member, probably has expertise or insider knowledge about the topic you have chosen to study. So send that person an e-mail to set up an interview. If you aren’t sure who might know something about your topic, call over to the academic department that seems closest to your topic. The staff at that department can often help you locate a helpful professor.

Inquiring: Planning to Solve the Problem

With your preliminary research finished, you are ready to start developing a plan to solve the problem. A plan is a step-by-step strategy for getting something done.

List a few possible solutions.

Usually, there are at least a few different ways to solve the problem. List the possible solutions and then rank them from best to worst. Keep in mind that some of the “best” solutions might not work due to how much they cost.

Map out your plan.

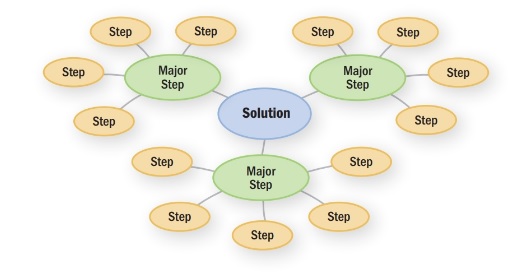

Again, a concept map is a useful tool for figuring out your plan. Start out by putting your best solution in the middle of your screen or a piece of paper. Then ask yourself, “What are the two to five major steps we need to take to achieve this solution?” Write those major steps around your solution and connect them to it with lines (Figure 21.1).

Explore each major step.

1. The university might look for grants or donations to help it do research on converting its campus to renewable energy sources like wind power or solar energy.2. The university might explore ways to replace the inefficient heating systems in campus buildings with geothermal heating and cooling systems.3. The university might convert its current fleet of buses and service vehicles to compressed natural gas or plug-in hybrids.

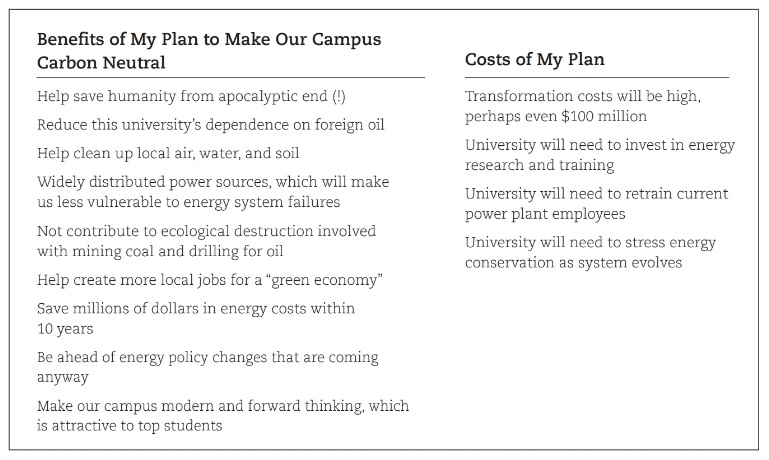

Figure out the costs and benefits of your plan.

Organizing and Drafting Your Proposal

separately. In other words, draft each major section as though it is a small argument on its own.

The Introduction

- State the topic. Tell your readers what the proposal is about.

- State the purpose. State the purpose of your proposal in one or two sentences.

- Provide background information. Give readers just enough historical information to understand your topic.

- Stress the importance of the topic to the readers. Tell readers why they should care about this topic.

- State your main point (thesis). Offer a straightforward statement that summarizes your plan and explains why it will succeed.

Weak: We think our campus should convert to alternative energy.Stronger: We propose the “Cool Campus Project,” which replaces our campus’s existing coal-fire plant with a local electricity grid that combines an off-campus wind farm with a network of solar panels on all campus buildings.

Description of the Problem, Its Causes, and Its Effects

The problem we face is that our campus is overly dependent on energy from the Anderson Power Facility, a 20-megawatt coal-fired plant on the east side of campus that belches out many tons of carbon dioxide each year. At this point, we have no alternative energy source, and our backup source of energy is the Bentonville Power Plant, another coal-fired plant 50 miles away. This dependence on the Anderson Plant causes our campus’s carbon footprint to be large, and it leaves us vulnerable to power shortages and rising energy costs.

The campus relies on coal-fired energy because, like many others in the United States, it was built in the early twentieth century when coal was cheap and no one could have anticipated problems like global warming. A coal-fired plant, like the one on the east side of campus, seemed like the logical choice. As our campus has grown, our energy needs have increased exponentially. Now, on any given day, the campus needs anywhere from 12 to 22 megawatts to keep running (Campus Energy Report 22).

Our dependence on fossil fuels for energy on this campus will begin to cost us more and more as the United States and the global community are forced to address global climate change. More than likely, coal-fired plants like ours will need to be completely replaced or refitted with expensive carbon capture equipment (Gathers 12). Also, federal and state governments will likely begin imposing a “carbon tax” on emitters of carbon dioxide to encourage conservation and conversion to alternative energy. The costs to our university could be many millions of dollars. Moreover, the costs to our health cannot be overlooked. Coal-fired plants, like ours, put particulates, mercury, and sulfur dioxide into the air that we breathe ( Vonn 65). The costs of our current coal-fired plant may seem hidden now, but they will eventually bleed our campus of funds and continue to harm our health.

Description of Your Plan

Draft your plan next. In this section, you want to describe step-by-step how the problem can be solved. The key to success in this section is to tell your readers how you would solve the problem and why you would do it this way.

The opening paragraph of this section should be brief. Tell readers your solution and give them a good reason why it is the best approach to the problem. Give your plan a name that is memorable and meaningful. For example:

The best way to make meaningful cuts in greenhouse gas emissions on our campus would be to replace our current coal-fired power plant with a twelve-turbine wind farm and install solar panels on all campus buildings. The Cool Campus Project would cut greenhouse gas emissions by half within ten years, and we could eliminate all greenhouse emissions within twenty years.

The body paragraphs for this section should tell the readers step by step how you would carry out your plan. Usually, each paragraph will start out by stating a major step.

Step 3: Install a Twelve-Turbine Wind Farm at the Experimental Farm The majority of the university’s electricity needs would be met by installing a twelve-turbine wind farm that would generate 18 megawatts of energy per day. The best place for this wind farm would be at the university’s Experimental Farm, which is two miles west of campus. The university already owns this property, and the area is known for its constant wind. An added advantage to placing a wind farm at this location is that the Agriculture Department could continue to use the land as an experimental farm. The turbines would be operating above the farm, and the land would still be available for planting crops.

In the closing paragraph of this section, you should summarize the deliverables of the plan. Deliverables are the things the readers will receive when the project is completed:

When the Cool Campus Project is completed, the university will be powered by a twelve-turbine wind farm and an array of solar panels mounted on campus buildings. This combination of wind and solar energy will generate the 20 megawatts needed by the campus on regular days, and it should be able to satisfy the 25 megawatts needed on peak usage days.

Discussing the Costs and Benefits of Your Plan

A good way to round out your argument is to discuss the costs and benefits of your plan. You want to show readers the two to five major benefits of your plan and then argue that these benefits outweigh the costs.

In the long run, the benefits of the Cool Campus Project will greatly outweigh the costs. The major benefits of converting to wind and solar energy include—

A savings of $1.2 million in energy costs each year once the investment is paid off. The avoidance of millions of dollars in refitting costs and carbon tax costs associated with our current coal-fired plant.

The improvement of our health due to the reduction of particulates, mercury, and sulfur dioxide in our local environment.

A great way to show that this university is environmentally progressive, thus attracting students and faculty who care about the environment.

We estimate the costs of the Cool Campus Project will be approximately $60 million, much of which can be offset with government grants. Keep in mind, though, that our coal-fired plant will need to be refitted or replaced soon anyway, which would cost millions. So the costs of the Cool Campus Project would likely be recouped within a decade.

Costs do not always involve money, or money alone. Sometimes the costs of the plan will be measured in effort or time.

The Conclusion

Your proposal’s conclusion should be brief and to the point. By now, you have told readers everything they need to know, so you just need to wrap up and leave your readers in a position to say yes to your plan. Here are a few moves you might consider making in your conclusion:

- Restate your main point (thesis). Again, tell the readers what you wanted to prove in your proposal. Your main point (thesis) first appeared in the introduction. Now bring the readers back around to it, showing that you proved your argument.

- Reemphasize the importance of the topic. Briefly, tell readers why this topic is important. You want to leave them with the sense that this issue needs to be addressed as soon as possible.

- Look to the future. Proposal writers often like to leave readers with a description of a better future. A “look to the future” should only run a few sentences or a brief paragraph.

- Offer contact information. Give readers contact information in case they have questions, want more information, or are interested in discussing the proposal.

Your conclusion should not take up more than a couple of brief paragraphs, even in a large proposal. The goal of your conclusion is to wrap up quickly.

Choosing an Appropriate Style

Choose a style that will be persuasive to your readers. Proposals are persuasive documents by nature, so your style should be convincing to match your proposal’s content. Here are some strategies that will make your proposal sound more convincing:

Create an authoritative tone.

Choose a tone that expresses a sense of authority. Then create a concept map around it. Weave these terms from your concept map into your proposal, creating a theme that sets the desired tone.

Use metaphors and similes.

Metaphors and similes allow you to compare new ideas to things that are familiar to your readers. For example, calling a coal-fired plant a “dirty tailpipe” will make it sound especially unattractive to your readers, encouraging them to agree with your argument. Or, you might use a metaphor to discuss wind turbines in terms of “farming” (e.g., harvesting the wind, planting wind turbines in a field, gathering the savings) because farming is a familiar concept to most readers.

Pay attention to sentence length.

Proposals should generate excitement, especially at the moments when you are describing your plan and its benefits. To raise the heartbeat of your writing, shorten the sentences at these key places in your proposal. Elsewhere in the proposal, keep the sentences regular length (breathing length).

Minimize jargon.

Proposals are often technical, depending on the topic. So look for any jargon words that could be replaced with simpler words or phrases. If a jargon word is needed, make sure you define it for readers.

Designing Your Proposal

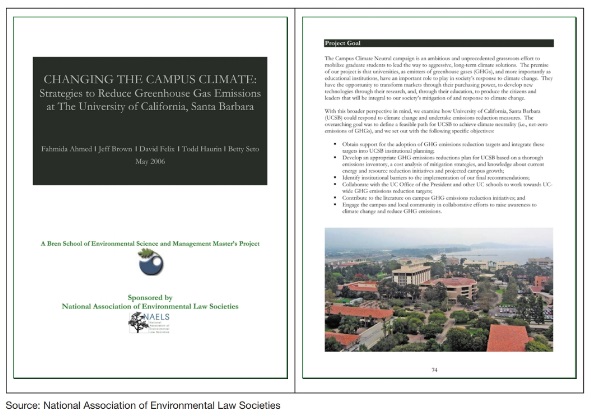

Your proposal needs to be attractive and easy to use, so leave yourself some time to design the document and include graphics. Good design will help your proposal stand out while making it easy to read. Your readers will also appreciate graphics that enhance and support your message.

Create a look.

Figure out what visual tone your proposal should set for readers. Do you want it to appear progressive or conservative? Do you want it to look exciting or traditional? Make choices about fonts, columns, and photographs that reflect that tone (Figure 21.3).

Use meaningful headings.

When your readers first pick up your proposal, they will likely scan it before reading. So your headings need to be meaningful and action oriented. Don’t just use headings like “Problem” or “Plan.” Instead, use headings like “Our Campus’s Global Warming Problem” or “Introducing the Cool Campus Initiative.”

Include relevant, accurate graphics.

Proposals often discuss trends, so you should look for places where you can use charts or graphs to illustrate those trends. Where possible, put data into tables. Use photographs to help explain the problem or show examples of your solution.

Use lists to highlight important points.

Look for places in your proposal where you list key ideas or other items. Then, where appropriate, put those ideas into bulleted lists that are easier for readers to scan.

Create white space.

You might want to expand your margins to add white space. Readers often like to take notes in the margins of proposals, so a little extra white space is useful. Also, extra white space makes the proposal seem less dense and easier to understand.

Microgenre: The Pitch

Pitches are brief proposals made to people who can offer their support (usually money) for your ideas. Pitches tend to be about one minute long, which means you need to be focused, concise, and confident. You’re promoting yourself as much as you are selling your idea. Here are some good strategies for making a persuasive one-minute pitch:

- Introduce yourself and establish your credibility. Remember that people invest in other people, not in projects. So tell them who you are and what you can do. Grab them with a good story. You need to capture your listeners’ attention right away, so ask them, “What if ?” or explain, “Recently, better way.”

- Present your big idea in one sentence. Don’t make them wait. Hit them with your best idea upfront in one sentence.

- Give them your best two or three reasons for doing it. The secret is to sell your idea, not explain it. List your best two or three reasons with minimal explanation.

- Mention something that distinguishes you and your idea from the others. What is unique about your idea? How does your idea uniquely fit in with your listeners’ prior investments?

- Offer a brief cost-benefit analysis. Show them very briefly that your idea is worth their investment of time, energy, or money. If relevant, tell them what you need to make this project a reality.

- Make sure they remember you. End your pitch by telling them something memorable about you or your organization. Make sure you put your contact information in their hands (e.g., a business card or résumé). If they allow it, leave them a written version of your pitch.

Elevator Pitch: “Mini Museum” by Hans Flex

What exactly is the mini museum? The mini museum is a portable collection of curiosities where every item is authentic, iconic, and labeled. It’s been carefully designed to take you on a journey of learning and exploration. The idea is simple. For the past 35 years I have collected amazing specimens specifically for this project. I then carefully break those specimens down into smaller pieces, embed them in resin, and end up with an epic museum in a manageable space. Each mini museum is a handcrafted, individually numbered limited edition. And if you consider the age of some of these specimens—it’s been billions of years in the making. The majority of these specimens were acquired directly from contacting specialists recommended to me by museum curators, research scientists, and university historians.

The collection starts with some of the oldest matter ever collected in the known universe—matter collected from carbonacious chondrites. These meteorites contain matter that is over 4 billion years old. Other meteors include some that have skimmed off the surface of Mars or the moon and then landed on Earth—each containing matter from those celestial bodies.

What’s next? Specimens from the strelly pool stromatolites that contain the earliest evidence of life on Earth. Also, a piece of a palm tree from Antarctica—yes, Antarctica. Everybody loves dinosaurs and the mini museum contains plenty of unique specimens from hundreds of millions of years ago, including favorites like the T-Rex and Triceratops. Even dinosaur poop.

As we migrate from the beginning of the universe to early life on Earth, we discover Homo Sapiens. Naturally, the mini museum also has many amazing and rare specimens documenting human history and culture. Mummy wrap, rocks from Mt. Everest, Trinitite, coal from the Titanic, and even a piece of the Apollo 11 command module to name just a few.

It’s space and time in the palm of your hand.

There is nothing else quite like it. The universe is amazing. I really wanted to remind people of that with this collection. How awesome would it be to own a group of rare meteorites, dinosaur fossils, and relics of some of the most talked about places and events in human history—all in the palm of your hand?

Key Takeaways

- Identify the problem you want to solve. In one sentence, write down the topic and purpose of your proposal. Then narrow the topic to something you can manage.

- Analyze the problem’s causes and effects. Use a concept map to analyze the problem’s two to five major causes. Then use another concept map to explore the effects of the problem if nothing is done about it.

- Do your research. Search the Internet and your library to collect sources. Then use empirical methods like interviews or surveys to help support or challenge the facts you find.

- Develop your plan for solving the problem. Using a concept map, figure out the two to five major steps needed to solve the problem. Then figure out what minor steps will be needed to achieve each of these major steps.

- Figure out the costs and benefits of your plan. Look at your plan section closely. Identify any costs of your plan. Then list all the benefits of solving the problem your way. You want to make sure the benefits of your solution outweigh the costs.

- Draft the proposal. Try drafting each major section separately, treating each one like a small document on its own.

- Your introduction should include a main point or thesis statement that expresses your solution to the problem in a straightforward way.

- Design your proposal. Your proposal needs to look professional and easy to read. Make choices about fonts, graphics, and document design that best suit the materials you are presenting to your readers. Revise and edit. Proposals are complicated documents, so leave plenty of time to revise and edit your work.

Proposal Example #1: “Ethical Chic: How Women Can Change the Fashion Industry” by Elizabeth Schaeffer Brown (Forbes 14 January 2014)

Globalization has made it easier than ever to ignore where our clothes come from. Are the workers paid equitably? Are their working conditions safe? Are their communities healthy? Many consumers may find it difficult to answer these questions, in part because most retail clothing makers don’t disclose adequate information about production.

Here’s the truth: When a garment is made in the developing world, the average percentage of the final retail cost that goes to the garment worker ranges from 0.5 – 4 percent. Most of us accept this status quo as the norm. Even the U.S. government, one of the largest consumers on the planet, orders clothing from the kind of factories that have killed so many people in Bangladesh.

For a long time, men have opened doors for each other in business. I believe that if we are to solve this issue, then we need more women to rise to leadership positions in the fashion industry. Women like Joey Adler from Industrial Revolution II (a client of mine at Uncommon Union) — and even celebrities like Olivia Wilde — are already opening doors and putting more ethical plans into action. As more women take on more authority as leaders in the fashion industry, they are poised to challenge the long-standing assumption that our ethics are limited by market forces.

The world is ready for women to remake the fashion of fashion — to bring into vogue putting people first. Here are a few ways we can get started:

Brand Ethical Fashion as Cool

Begin to educate consumers about the importance of ethical fashion. Social entrepreneurs on the sourcing side of the equation know that, in order to change how we think about commerce and how we conduct business as entrepreneurs, leaders and consumers, the industry needs to work hard to develop customers who will make ethical choices.

Start by identifying public figures and entertainment stars — e.g., trendsetters like Donna Karan (Urban Zen) and Hugh Jackman (Laughing Man) — who care about developing an ethical framework for capitalism. Leverage their authority and influence to bring ethical fashion into the forefront of public attention. Rather than trying to appeal to people’s conscience, begin to make the ethical choice the fashionable one.

Consider the Product

Develop a product with a clearly defined ethical pedigree. To do so, you need to be able to document the life cycle of the product from inception to the store shelf. Who designed the product? Who made it? What is it made from? To what extent was the welfare of the people involved in the process taken into account?

The answers to all these questions need to serve the purpose of marketing the product. Some stages of a product’s lifecycle (especially in the developing world) can be difficult to verify and control, so be careful. You need to offer proof.

Market Smart

Lastly, use both the quality and appeal of the product and its pedigree as a marketing tool. Many if not most people want to make the ethical choice — they just need help getting there. Educate consumers about the long chain of events starting with textile production and ending with the store purchase. Whenever possible, show public figures wearing the product or discussing the product.

Make it personal: Use photographs and story to creative a narrative about the product so that consumers feel that they are not just buying an object but becoming part of a story.

If consumers then begin to ask questions and demand accountability — if humanitarian, health, and environmental concerns start to drive the fashion industry — ethically sourced fashion will become the norm. The status quo will change. In the end, change depends on the willingness of workers, consumers, and entrepreneurs to step into the unknown. Let us be some of the first to insist on a better world.

Proposal Example #2: “Ban Cars” by Alissa Walker (Gizmodo 1 June 2016)

In December of 2015, 195 countries announced that even a global effort to reduce emissions probably won’t prevent the catastrophic warming of the planet. But there is a way we can reach our climate goals. It’s not a pledge. It’s not a tax. It’s easier than that. We ban cars.

Aside from a single panel discussion, the historic COP21 summit didn’t address cars much at all. The United Nations issued one statement, reminding us that 25 percent of all energy-related emissions in the atmosphere are from transportation, a percentage which is expected to grow to a third. To attempt to reach the climate goals, it says, at least a fifth of all vehicles worldwide should be electric by 2030.

Now consider that there are about a billion cars crawling the Earth’s surface right now, a number which might double as soon as 2030. How fast that figure grows depends on how dramatically developing nations like China and India experience increases in vehicle ownership. But no single country is currently driving more cars around this planet than the United States of America. 2015 was a year of record-breaking auto sales.

Like there is no clean coal, there is no clean car. So we don’t have to get more electric cars on the road. We have to get more cars off the road. Fast.

Banning cars is as simple as it sounds: It’s restricting private automobiles from entering a geographic area. You might have already seen how this works in a pedestrian-prioritized historical district, which is common in bigger cities. So we start the ban there, in the biggest cities: Where about half the world’s population lives now, where car ownership is already low, and where existing housing density and transit infrastructure allow people to easily live without automobiles. These are also the places you can make the greatest impact as the population in cities is growing—70 percent of the world will live in a city by 2050, as part of multiple urbanizing trends around the world.

But it’s not just about banning cars. Cities also have to help their citizens live without a car. This means they must approve taller buildings, get rid of parking minimums, and expand public transit options. Build rail instead of roads. Turn gas stations into bike kiosks. Convert parking lots to sidewalks. Provide a fleet of low-speed zero-emission vehicles (like golf carts!) to make deliveries and help residents get around. And introduce better technology solutions to help everyone navigate the city more efficiently.

Does it sound impossible? It’s already happening in a lot of places. Oslo is working on banning all cars from its city center by 2019. So are Helsinki, Madrid, and Hamburg. London has heavily restricted them in its downtown. Paris has not only restricted vehicular access, but is also prohibiting cars built before 1997. A thriving business district in Johannesburg got rid of all its cars for a month. Even the US has done this, on a smaller scale: New York City has barred them from Times Square, and San Francisco has kicked them off a stretch of its Market Street.

In fact, on any given weekend, cities all over the planet set aside large swaths of their neighborhoods for walkers and bikers as part of regularly scheduled car-free festivals. These are bringing about permanent change: Bogotá began banishing cars from its streets every Sunday and used that momentum to develop one of the most inspiring, low-cost transportation systems on the planet in less than 20 years.

Cities are doing this because we know it’s better for the humans who live there. Science has proven that almost every other way of getting around is better for our bodies and our minds. Banning cars from major cities worldwide would save millions of lives, and not just by reducing crashes: Removing cars from roads shows a drastic and immediate improvement in both carbon emissions and in dangerous particulate matter—the kind that kills about three million people globally a year. Banning cars part of the time, like on alternate days, doesn’t work in the long run because cities are still allowing some cars in. People find ways to get around the rules and cities don’t have the money to enforce them. All cars must go.

Although we can see with our own eyes how much better the air in our cities will be without cars, there’s another crisis happening on the ground. Cities that are built for cars require goods and services to be moved across farther and farther distances. Each building’s carbon footprint includes not only the materials and methods which are required to build it, but all the infrastructural systems required to sustain it. If those systems are served primarily by cars—deliveries, workers, residents, visitors—the building’s carbon footprint balloons. A city built for cars requires far more energy to power it.

Making too much room for cars is also making our cities more expensive. Parking, for example, takes up as much as 14 percent of all land-use in some cities. In Los Angeles County, that’s 3.3 spaces for every vehicle. Less room devoted to cars frees up more space for the additional housing we so desperately need. A city instantly becomes more accessible to all when it plans for the well-being of its citizens, without the assumption that everyone has an extra $9,000 per year to pay for a way to get around it.

The promise of autonomous, zero-emission vehicles can be part of the solution, but only if we think about them as another form of public transit: As shareable, summonable vehicles which will replace taxis (or other on-demand rides). By some estimates, when autonomy arrives, cities will need to dramatically reduce the overall space allotted to cars.

But wait! What if autonomous cars don’t happen—or at least not as quickly as we’d like? That’s exactly why the process of evicting cars from all major cities right now is more critical than ever—because this is really about remaking cities into more livable places long before that future arrives.

And if you don’t live in a city—or don’t want to—banning cars benefits you, too. Besides the obvious health benefits, more efficient transportation systems will make it easier to get where you need to go and reduce the overall costs of goods and services brought to your door. If you need a vehicle out where you live, you can simply borrow one from a local zero-emission fleet. It will take many years and a lot of work to reverse the US away from decades of engrained commuting culture, but it can happen. We start with the cities, where more of the population lives, and let the positive impacts ripple out.

In addition to the 195 heads of state, 1000 mayors were in Paris for the climate talks, pledging to move their communities towards a renewable energy future—even if an international accord wasn’t reached. City leaders have a lot more power to bring about change than 195 countries trying to strike an agreement. A mayor may not be able to shut down a power plant even if it’s inside city limits. But she can make it impossible to bring one more car into her downtown.

If you don’t think that one car will make a difference, consider this. Right now, about three percent of all trips globally are taken by bike. A big study by UC Davis and the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy says that reducing car use enough to double that figure to six percent by 2050 could make a game-changing impact. Cities would save $24 trillion and the planet would reduce CO2 emissions by nearly 11 percent. That’s enough to prevent the increase in transportation-related emissions that the UN predicts. And the world would be happier and healthier for it.

A generation from now we’ll look back on this one-hundred year blip in human history and shake our heads. We’ll remember this failed experiment, our temporary lapse in judgement. But we have to reverse this trend now, before we hand over any more of our cities to an antiquated, dying technology that’s killing us right along with it.

Cars are an old idea from the past. But believing that cars are the future could destroy our entire civilization.

Alissa Walker is the former urbanism editor at Gizmodo. She connects people with where they live through writing, speaking, and walking. As the urbanism editor at Curbed, she authors the column “Word on the Street,” highlighting the pioneering transit, clever civic design, and game-changing policy affecting our cities.

Alissa has been named a USC Annenberg/Getty Arts Journalism Fellow for her writing on design and urbanism, Journalist of the Year by Streetsblog Los Angeles, and in 2015 received the Design Advocate award from the LA chapter of the American Institute of Architects. She is also the co-founder of design east of La Brea, a nonprofit that has received two National Endowment for the Arts grants supporting its LA design events.

Alissa lives in Los Angeles, where she is a mom to the city’s two most enthusiastic public transit riders.

Proposal Example #3: “Solving Twitter’s Abuse Problem” by Haje Jan Kamps (Medium 29 February 2016)

Twitter is awesome, but unless it gets its abuse problem under control, it’s going to struggle to attract new users.

![]() Trigger Warning: This article is about abuse and harassment online. As you might expect, it contains some strong language and some unpleasant concepts.

Trigger Warning: This article is about abuse and harassment online. As you might expect, it contains some strong language and some unpleasant concepts.

Edited: Most of the profanity and offensive language of the original article has been edited. To see the original article with its explicit content, go to https://haje.medium.com/solving-twitter-s-abuse-problem-3f1f8ac1a0d2.

I was born in the early 1980s. Bullying was something that happened. A lot. To me, to people around me, to my friends, and to people I knew. Throughout all of this, there was reprieve. With a few very rare exceptions, as soon as the bullying victim got home, threw their backpack into the corner of their bedroom and sunk into the sofa to bury themselves in a book, they were safe. Bullying was something that happened in the playground. On the way to and from school. In the youth centre. In the shop. At school. At work.

But once you were home, you were safe. That was the 1990s. And then everything changed.

Enter the Internet

The internet happened. A new world of information, entertainment, and a chance to escape, for sure. But also an avenue for abuse, harassment, and bullying, with an additional pinch of insidious venom added to the mix: A combination of availability and anonymity.

The 24/7 nature of the internet meant that in a period of time spanning less than a generation, people moved a large portion of their lives from meatspace to cyberspace. You’d be crazy not to, really: There’s such a vibrant, incredible world on the internet. There are hobbies to share, and conversations to be had. But it also meant that closing your home’s door behind you was no longer a guarantee that you were safe from bullying.

As for anonymity… It doesn’t take a lot of imagination to see how, when the risk of being caught is taken away, that bullying can become a much more effective pursuit for those so inclined.

Why is this such a big problem for social media?

For this article, I’ve largely focused on Twitter, both in thinking and in research, not least because it’s the platform closest to my heart — 2016 marks my 10th anniversary as a Twitter user.

Twitter is the #1 platform for breaking news. Facebook dreams to have even a fraction of the influence Twitter has on this front. Twitter is the must-have platform for journalists and media professionals. The public frequently learn of breaking news stories via twitter, and — come to think of it — rarely does a news broadcast go by without mentioning Twitter. Never has this been more obvious as when the presidential hopefuls are meeting to debate ahead of the 2016 elections here in the US.

But there’s a dark side too: Imagine if you stumble onto twitter for the first time and start looking at the #GOPdebate hashtag. You’ll be met with stuff like this:

There’s an excellent reason why most people avoid reading ‘below the fold’ (i.e. the comments) on the internet. The comment section is where, from behind a veil of anonymity, people’s personality quirks come to play with impunity, whether that’s racism, wild rumours based on very little indeed, name-calling, or any number of other sins.

The blessing and the curse for Twitter is that they an oft-used medium for online debate to offline events. Sports events, political events, breaking news stories; the live commentary is a huge part of why Twitter is awesome. At the Oscars, for example, when the Best Actor was announced, Twitter peaked at 440,000 tweets per minute. That’s mental.

But that’s also the problem: The nature of these events means that this might well be someone’s first interaction with the platform, and when it is, you’re likely to come across a tremendous amount of content that might make you think twice about signing up for an account. It’s easy to imagine someone reading the three tweets listed above, and doing the digital equivalent of peeking into a bar you’re not familiar with. One quick look, and you’ll go “You know what? I don’t like the look of this, let’s go somewhere else”.

It’s no secret that Twitter is struggling to continue to grow, and I’d suggest that the above is at least part of the reason for this.

In this article, I’m exploring abuse and harassment on social media — especially on Twitter. I’m doing so in an effort to see whether it’s possible to come up with some solutions, or at least some suggestions, for how to help reduce what is a huge problem — big enough, in fact, that it may be a significant hindrance to further growth of my favourite social media platform.

Part 2 — Why creating a sensible policy on online abuse is complicated

Everybody agrees they want freedom, but they can’t agree what ‘freedom’ means.

Whenever you talk about considering to do something about online abuse, you’ll generally find that people are split into two camps.

Both camps agree that what they want is freedom, and you’d think that means they want to the same thing; but that’s not the case. They disagree on the type of freedom they want; they disagree on what freedom means.

In short, it’s a dichotomy between freedom to and freedom from.

Freedom to Speak

One side of the argument believes in the freedom to say anything — Freedom of Speech. As a journalist, I’m an ardent believer in freedom of speech. A government that tries to repress the free sharing of opinions, ideas, and information is inherently problematic.

Those arguing for unfettered freedom of speech on social media will often argue that freedom of speech should be unabridged and unrestricted, without any limits. The argument goes that freedom of speech is protected by the constitution (in the US) and various other laws (elsewhere), and that preventing anyone from saying anything is an infringement on those rights.

Suggestions that some types of content aren’t welcome on a platform are often met with comments such as this one:

Freedom from Abuse

The other camp wants a different type of freedom: They are usually also believers in freedom of speech, but with certain limitations. Those limitations are usually related to threats, abuse, and illegal activities.

Put simply, they argue for a freedom from certain types of communication, especially when it is aimed at them, and when it causes harassment, distress or alarm. This includes abusive language, threats of violence, or threats to have personal information shared (‘doxxing’).

As I’ll discuss in Abusive or Not below, there are cases where something is obviously not abuse (although it might seem so at first glance), and where something is very obviously abusive. Those matters are less problematic than the gray areas in between — It is hard to find a consensus about where the limits are for where a conversation crosses over from a heated debate into abuse or harassment, for example.

The friction is where the freedoms clash

Neither on the internet nor offline (e.g. Schenck v United States) is anyone granted complete freedom of communication. Sharing a database of stolen credit card details, peddling child pornography, and joking about blowing up an airline will all result in police knocking on (or, in some cases, knocking down) your door.

In addition, being banned from expressing certain things from a site like Twitter or Facebook, is not an infringement on one’s freedom of speech. Social media platforms are private companies, and they are within their right to determine what they think is appropriate behaviour for the platform. In fact, there are already differences between Facebook and Twitter in this regard: Facebook has a strict no-nudity rule, whereas Twitter doesn’t. Seen from a freedom of speech / first amendment perspective, nobody is prevented from starting their own social network, where the types of communications banned from other platforms is welcome.

If we agree that absolute freedom isn’t wanted, and it’s impracticable to manually review every dubious tweet, the solution has to lie somewhere in between those two extremes.

I’ve discussed earlier in this article about the technology challenges of automatically trying to determine what is abusive and what isn’t, but policies go far beyond what is possible; it’s about what you should be doing.

Creating an abuse policy

I helped moderate the comments at a major news site for a while, and I was part of the team that put together a user-generated content policy for a major UK broadcaster. The most important lesson I learned in the process is that policing content is immensely complicated.

The content that causes the most problems is the same content that people are emotionally attached to. When that content is removed, it evokes some rather extreme reactions, from the type of people who were likely to post abusive content in the first place. Creating policies and policing them is a thankless, horrible job — but it’s an important one.

Moreover, the act of creating a policy in the first place is contentious. A site such as Twitter has a decade’s worth of unwritten rules and a culture of sorts. The first time a comprehensive policy is created and disseminated, it will be the first time the site draws a circle around what is OK and what is not, which will almost certainly cause a huge amount of debate and upheaval — especially among the users who operate close to, and occasionally beyond, the lines of acceptability.

There’s also a consideration around the different types of abuse — or the wider ‘safety’ element of social media. Phishing, scamming, doxxing, threats, harassment, impersonation, encouraging people who are already suicidal to ‘go through’ with the deed, Swatting, sharing / distribution of illegal content, facilitation of crime (i.e. advertising illegal goods and services), aiding / encouraging illegal activity, and even potentially going into copyright infringement and plagiarism issues. It’s hard to overstate how big the topic is, but it would be of great help to at least clarify some of the Twitter Rules as a start.

My policy experience is relatively limited, so I’ll leave the specifics to a group of people more qualified and experienced than myself. I will weigh in on this, however:

- It’s crucial that any actions that are taken as a response to abuse are taken transparently.

- There must be a way to correct mistakes made in the process of implementing the policy.

- There needs to be a clear set of guidelines for what is OK and what isn’t.

- Reported content must be dealt with as quickly as possible. In the case of Twitter, a news source that operates in the fractions-of-a-second timeframe, rather than the hours or days of most other websites, I’d suggest that ‘as quickly as possible’ should mean ‘less than an hour’.

- The people dealing with abuse need a strong suite of tools to help draw contextual information from the posts they’ve had reported.

An aside on public figures

A complication in the creation of an abuse policy is the discussion of ‘public figures’ — people who actively invite public attention, including musicians, artists, and political figures.

An abuse policy would probably need to address all of these issues, both for private citizens participating in a public debate, and for public figures, who — for better or worse — often have different expectations around the sort of things they ought to be able to tolerate.

Conclusion

- Creating an abuse policy is difficult, and impossible to make ‘correct’ for everyone involved: Emotions run high.

- You cannot placate both the people who believe they deserve the freedom to say anything, and the people who believe they deserve freedom from abuse. A good abuse policy is likely to impinge on what both of these groups perceive as their rights.

- Not easy, but it’s important that any policy that is implemented is transparent, easy to understand, and hard to misinterpret.

- People have different tolerances and expectations for abuse, and a policy should either reflect that, or pick an appropriate middle ground.

Part 3 — Abusive or not — A challenge of sentiment analysis

For the purposes of learning more about abuse and harassment online, I decided to take a deep dive into social media’s murky waters.

Given that I’ve done a few projects using Twitter’s API in the past (I analysed who Twitter’s Verified users are, and did a project on racism on Twitter), I decided to limit my analysis t0 Twitter.

Abusive or not, here I come…

Trying to determine whether any given tweet is abusive is largely a problem of sentiment analysis. It is the step between “I can transcribe your words” and “I understand what you mean”.

For example, when you ask Siri “What is 5 degrees in Fahrenheit”, and Siri responds with “5 degrees Fahrenheit is 5 degrees Fahrenheit”, it sounds quite philosophical, really, but it isn’t actually all that useful. While Siri correctly heard what I said, she didn’t understand what I meant.

I ran into similar problems when trying to analyse tweets and determine whether or not they were to be considered ‘abusive’ or not. I already suspected that I would need to look beyond the words per se, but I hadn’t realised quite how much of a challenge that would be.

It turns out, for example, that there’s a sizeable group of people on Twitter who say absolutely horrendous things to each other. On first glance, it seems like these people are very close to digging out the machetes and having at each other… Except the torrents of abuse that are unleashed on each other is a sociolect of sorts, where the people communicating with each other use a vocabulary that would make a late-night sysadmin blush.

This isn’t even close to the worst of the worst: This is a perfectly normal day on Twitter.

For example, early on in my research, my abuse analysis bot picked up a conversation because of a tweet that said ‘you f***ing slut’. It received a rather high abuse score, as you might imagine, but I had to laugh when I looked into the context:

This tweet was the epiphany for me, and reminded me of a situation I like to refer to as the James is a c*** problem — more about that in just a moment.

People do say all sorts of things to each other, and while one phrase may be acceptable among your closest friends after a few beers, you wouldn’t tweet it at your acquaintances or workmates. And even then, that isn’t necessarily true either: maybe you do have a group of acquaintances between whom coarse language is OK.

Imagine, for a moment, then, that you’re trying to understand all of the above from a tweet that just reads @username is a c***. How do you determine whether this tweet is abusive, just from those four words? You couldn’t. You can’t.

I probably wouldn’t tweet that exact phrase, even at my best friends. But others might. In fact, they do. Frequently.

Sometimes, spotting abuse is easy.

I’ve read more than 100,000 abusive tweets over the past couple of months. Suffice to say that it gets a little disheartening after a while. There are a lot of… You know, this is already a pretty explicit-laden blog post, and I think this is one of those times where using a soupçon of strong language might just be warranted… There are a lot of hate-filled users out there.

But, most importantly… don’t fool yourself into thinking that the above is cherry-picking. It isn’t even close to the worst of the worst: This is a perfectly normal day on Twitter.

The abuse ranges from name-calling to death and rape threats, and everything in between. The above tweets all have something in common: My little Twitter bot correctly identified these tweets as abusive. That’s the good news.

Given that it’s relatively easy to identify tweets like these on Twitter, it is another matter what Twitter can or should do about these posts. And, considering that there are thousands of them, it’s not going to be a small job to clean that mess up.

The bad news is that it’s this easy to determine something as abusive in just 20% of cases. 15% of the time, it’s downright impossible, and in the remaining 65%, it becomes incredibly, deceptively hard to determine whether what appears to be abuse, harassment, and bullying, actually is.

Allow me a digression to explain why actually determining whether a given 140-character string of characters is abusive is such a hard problem:

The ‘James is a c***’ problem

Whenever I speak on the topic of context and abuse, I tend to refer to the challenge of context as the ‘James is a c***’ problem. The challenge is as follows:

Is it OK to call your co-worker a c***?

In the US especially — where that word is usually referred to only as the ‘c word’, I’d hazard that for many — probably most — people, the answer is an emphatic and enthusiastic ‘no’. In England, it’s still one of the less acceptable swearwords, but it’s in more regular circulation.

Is it OK to have a T-shirt made that says ‘James is a c***’, and then give it as a gift to James?

In some work places, this is par for the course. I once worked somewhere where this exact interaction happened: I had a t-shirt made for my co-worker that had his name on it, then ‘is a c***’. Not only did he love it, he wore it. Proudly. At work. At a company with well over a thousand employees. The CEO spotted it, sighed, shook her head, and went on with her business.

At this point, you’re probably wondering whether I’m completely insane (you might just be onto something), or whether you’re missing something.

You are. Missing something, I mean.

The ‘something’ that’s missing from the above narrative is a thick layer of context.

The job in question was well over a decade ago; one of my very first jobs straight out of university, as the online editor for a magazine focusing on modified cars. When they decided to give me the job, the then-editor nervously asked me “er, are you OK with a bit of banter?” “How do you mean?” I asked. “Well, you know… Banter.” “I give as good as I get, I suppose”, I replied, and that was the first flag in the ground for what was to become one of the most outrageous jobs I’ve ever had. The pay was terrible, but I travelled all over the world, got to drive all sorts of bonkers cars, and got myself into all manner of insane situations. It was tremendous fun.

You’ll have to forgive the aside, but I’m trying to explain that there is a backdrop against which giving a t-shirt that reads ‘James is a C***’ to a colleague is actually a pretty normal thing to do, but to understand why, you’ll need a lot of context.

All of which can be summarised as follows:

Sometimes, it’s hard to determine abuse

If you are just scanning for phrases like ‘you’re a c***’ (or misspellings thereof), as I was doing when I first started the research project, the above triggers the abuse bot, with a high score. But in this particular case, it probably isn’t abusive — both the to-and-fro seems relatively jocular, and there is metadata available that contra-indicates the abuse status (more about meta-data a bit later).

What if we make things more complicated?

In this case, user 1 calls user 2 a whore, but user 2 favourites user 1’s tweet. Then they go back and forth for a while. Abusive? Not abusive? On the face of it, it’s hard to say, but I’d err on the side of ‘probably not’. Interactions like this happen by the thousands every week on Twitter.

Only by analysing all the factors (see adding context to analysis, below) do you stand a chance of identifying whether these tweets are actually abusive.

Sometimes, it’s complicated…

Sometimes, my little bot successfully identified barrages upon barrages of abuse against a particular person.

Martin Shkreli, for example, has been in the media a fair bit recently, for hiking the price of a drug, for being under investigation for a Ponzi scheme, for buying the only copy of a Wu Tang album for $2m, and for supposedly causing a multi-day delay to Kanye West’s most recent album.

Whether you love or him or loathe him, Shkreli apparently revels in the attention, and his Twitter stream would be ill-advised for someone who is trying to stay out of the limelight.

And yet, while Shkreli does appear to fuel the fire at times, egging on his detractors, some of the attacks move from what I learned to be regular run-of-the-mill abuse, and over into something more sinister…

The challenge becomes one of policy rather than one of automatic detection: While the attention aimed at Shkreli is abusive in nature (“Fuck you you piece of shit making money off defenseless people fucking cocksucker scumbag asshole”, for example, is relatively unlikely to be meant as a phrase of endearment), is there a limit where a not-so-gentle ribbing turns into actual abuse? This is a challenge both for automated abuse detection algorithms and for the policy team.

And sometimes, it’s impossible…

“If you get a blade sharp enough, it’ll cut through anything”

Some tweets are extremely hard to analyse as to whether or not they are abusive, and highlight why even the most sophisticated algorithms are bound to get stumped from time to time.

One particularly heart-breaking example of that is illustrated by Lindy West in This American Life’s episode 545 (there’s a transcript, too, but do listen to it, it is incredible storytelling). In short: Lindy’s father suddenly created a Twitter account and started tweeting at her. Except her father had recently passed away, and the twitter account was created by one of her abusers. “I thought I was coping”, Lindy says in the episode, “But if you get a blade sharp enough, it’ll cut through anything”

Taking a step back from the human side how horrendous it must be to receive such a message, there’s another challenge: No amount of technology can catch this type of abuse.

Imagine being Beck and receiving the tweet “I may just take your advice at your show tomorrow”. On the surface, that looks like a supportive tweet, but there’s an off-line context here: his most famous song includes the phrase ‘i’m a loser baby, so why don’t you kill me’, and ‘taking your advice’ could, in fact, be a death threat.

Or put yourself in the shoes of David Axelrod, a political commentator who has been candid about his father’s suicide, receiving the following:

Actually, this tweet is a bad example, by virtue of the fact that my Twitter bot did correctly identify this tweet as potentially abusive — but it only did so because it at some point learned that ‘kill yourself’ is an indicator for abuse. If the tweet had read “I hope you follow in your father’s footsteps”, it wouldn’t have turned up on anyone’s radar — except, most crucially, David’s.

The point I am trying to make here is that, with the volume of tweets every day, even if they wanted to, it’s simply impossible to filter out all the abuse.

And then there’s images

All of the above continues to be true — but gets a hell of a lot more complicated — when you start considering Twitter’s image-as-text problem. This one, for example, is hard to analyse on several levels:

Is it a quote from a TV show? (i.e. innocent)? Is it banter among friends (i.e. neutral)? Is it a tweet to a person who is depressed and expressing a desire to end their life (i.e. deeply troubling)?

For my research, I decided to give images a slight score for likelyhood of abusive, but realistically, it’s neutral: An image is as likely to be of a kitten as it is of a corpse or a rape threat. Doing image recognition and OCR is possible, of course, but with the volume of images being sent through social media, that particular challenge was beyond the scope of this project.

Adding context to abuse analysis

The biggest — and in retrospect most obvious — conclusion I drew from my research is that it isn’t the tweets themselves that are a strongest indicator for most of the internet abuse — it is their context.

In fact, it turned out that I was more successful in identifying abusive tweets when I turned my algorithm inside out: Instead of trying to find tweets that were abusive, and then determine whether they were from context, it was easier to find tweets that score high for abuse by taking context into consideration first, and then dropping any tweets that didn’t contain abusive text in the tweet body.

In part, that can be explained by the simple fact that 140 characters isn’t a lot of text to analyse. Even just digging into the metadata, there was a wealth of information — far more than you can deduce from the tweet itself.

The below indicators were ones that came up after considering the data sources I had available to me as part of Twitter’s APIs, and an educated guess as to whether each data items were of use in determining abuse. Subsequently, I ran a large series of experiments on the data set to try to determine the weighting of each indicator. I do have a stab at precise weightings, but I anticipate that a more experienced data scientist than myself could write an automated algorithm to help educate how influential each variable is. For the purpose of this article, I’ve abstracted the specific weightings to more generalised descriptions.

Note: For clarity, I’m using the phrases Abuser and Target to identify the sender and recipient of a public tweet, even if the tweet/metadata determines that the tweet is not abusive.

Contextual indicators of abuse:

- How many followers does the abuser have? (Fewer than 50 is bad news, and fewer still increases the abuse risk)

- How many friends does the abuser have? (Fewer than 50 is bad news, and fewer still increases the abuse risk)

- How old is the account the abuser is using? (Less than a month is bad, less than a week is worse, less than a day is really bad news)

- What is the ratio of followers-to-friends? (If the abuser follows more people than what follows them, that’s an indicator of abuse. If their friend-to-follower ratio is 3:1 or above, it’s a strong indicator)

- What is the followers-to-followers ratio between the abuser and the target? (A ratio is 100:1 or higher is a strong indicator of abuse)

- How many times has the abuser tweeted? (Fewer than 100 tweets is bad, and it gets worse the fewer tweets there are)

- Is the abuser an ‘egg’? (i.e. did they set a picture? Yes is bad news)

- Has the bot caught the abuser been being abusive before? (Once is usually a strong indicator. Habitual abuse sends the risk of abuse off the charts)

- Has the target of abuse been abused before? (The more, the higher the risk of future abuse)

- Is the tweet part of a conversation? (If it is an at-mention out of the blue, that’s bad news.)

- Does the abuser follow the target? (If no, it’s a weak indicator of abuse, but there is some correlation)

- Is the target verified? (If yes, it can help inform some of the other indicators of the algorithm. Verified users also seem to get a disproportionate amount of abuse)

Contextual contra-indicators of abuse:

- Is the tweet part of a conversation? (The more tweets back-and-forth in that conversation, the less likely it is to be abusive)

- Has the abuser and the target had interactions in the past? (Yes is usually a contra-indication, but not always; it could mean two people constantly at each other’s throats, or two people who used to be friends but are no longer)

- Does the target follow the abuser? (If yes, it’s much less likely to be abusive)

- Do the target and abuser follow each other (If yes, it’s dramatically less likely to be abusive)

- Is the abuser verified? (If so: unlikely to be abusive. In fact, in the six weeks my bot was running, it only found a couple of instances of abuse by verified users, as I’m writing this, those users are no longer bearing the blue tickmark.)

- Did the target favourite the abusive tweet? (A favourite is usually a strong contra-indicator of abuse).

- Did the target retweet the abusive tweet? (A retweet can go either way; It is usually positive, but some that are in the crosshairs of abuse retweet their abusers, presumably to shame them).

And that’s just the beginning…

And that is just the information I had access to via Twitter’s APIs — Twitter itself has access to a metric tonne of additional information.

A few, just off the top of my head:

- I wouldn’t be surprised if users with a verified phone number are much less likely to be abusive.

- If the twitter account is tied to a mobile app, it may be possible to identify what other accounts are tied to that mobile device, and draw conclusions from that.

- Does the target block the abuser? Blocking, muting, and reporting tweets as abusive would likely be strong indicators of abuse, and could be added to the algorithms.

- It may be possible to do IP analysis on new accounts, and see whether they are likely to be abusive or not.

Findings

This section is a summary of some of my findings from running a gradually-refining bot against Twitter’s API over six weeks, to determine whether it’s possible to categorically identify abusive tweets or not.

The bot scores tweets on a scale from -50 (i.e. definitely not abusive) to +250 (i.e. yeah, I’m gonna need you to take a seat over here, son). From my research, anything scoring lower than -20 is >95% unlikely to be abusive, and anything scoring over +130 is >95% likely to be abusive. Any tweet scoring over 200 is abusive; I haven’t identified a single false positive for tweets scoring that high so far, but more research is required.

Tweets scoring less than -20 and more than +130 cover roughly 30% of all tweets analysed, which is, well, a bit disappointing: A 30% determination rate is not ideal — my goal was to successfully categorise more than 90% of tweets.

There is a silver lining, however: The tweets scoring over 150 or so are the vast bulk of the horrendous abuse going on on Twitter. Using this scoring system in combination with a pattern-matching system tied to the ‘report abuse’ system means that you could leverage the various systems to quash abuse. For example, in the case of the person receiving dozens and dozens of the same abusive tweets; they all followed a very particular pattern. If one of those tweets is reported and removed by Twitter, it’d be possible to feed that one into an algorithm to also automatically remove all the other abusive posts (at a minimum) and consider taking further action against the accounts in question.

Of course, all of this research is done in isolation; I haven’t had help from Twitter — on the contrary, in fact: at 180 API requests every 15 minutes, the bottleneck of my analysis was largely Twitter’s API limitations. The reason for this is that some of the analysis was ‘expensive’ in terms of API calls (to find out how many tweets are in a conversation, you have to ‘walk up the tree’. Each post in a conversation takes a separate call, so on the few occasions I ran into conversations that were 80–90 tweets back and forth, that munched up half my API quota for a 15-minute period. To find out whether two arbitrary Twitter users follow each other, that’s an additional API call. To find out whether two users have interacted in the past, that’s another search API call). On the flipside, if Twitter is interested in doing this research in more depth, they could very easily do so, either by commissioning a data analytics team in-house, or by allowing a team of researchers access to an API key with more API calls, say, during non-peak hours.

Conclusion

- Analysing tweets for abuse is a surprisingly difficult problem

- Context is everything, and the historical relationship between the users in question is often a better indicator for abuse than the tweets themselves

- The Twitter API is too restrictive to really be able to analyse a big enough dataset to draw more conclusive, er, conclusions.

Part 4 — Solving Twitter’s abuse problem

There is no doubt in my mind that on *my* Twitter, there is no space for threats, abuse, and harassment.

In this final section, I’m trying to pull together some suggestions for how Twitter can tackle its abuse problems.

Step 1 — Outline the problem, create a good policy & set clear goals

A strong response to abuse and harassment starts with a trio of obvious places to start: For one thing, Twitter needs to clearly articulate what the problem is, and why it is a problem worth solving for the organisation. Without this piece of work, you may as well not go any further: It’s crucial; the foundation for everything that happens next.

As discussed earlier, creating a good abuse policy isn’t easy. Quite the opposite, but having a clear policy in place is important both for internal communications to the teams that will implement the solutions, and for external communications as a line in the sand: X is fine, but Y is not.

Finally, a set of metrics and goals to track whether all of this is working, and to identify where more thought, tech, or resources are needed.

Step 2 — Full buy-in or bust.

Once a solid policy draft is in place, it’s crucial that there’s a 100% buy-in from the senior team at Twitter, possibly even at a board level. As discussed in the piece on why creating a policy is hard, I anticipate some strong disagreements towards whether Twitter wants to be leaning towards safety or 1st amendment rights.

It takes a strong CEO to champion a fight against abuse and harassment, and Jack has stated on several occasions that he’s willing to pick that fight — but at least from the outside, it appears that not nearly enough has been done so far.

But, assuming that there is a clear policy, and a comprehensive buy-in to put an end to harassment and abuse on Twitter, it’s possible to start the work…

Step 3 — Run strong post-moderation

The first part of implementation is to overhaul the post-moderation process, i.e. how do you deal with posts that have been reported? This includes creating a set of tools and comprehensive training for the people dealing with reported posts.

It becomes crucial to empower the operators to take whatever action necessary to deal with an abuser, whether that’s a warning, the deletion of a tweet, the suspension of an account, or whether it triggers a more serious action, such as starting a police investigation.

The tools should include automated ways of doing contextual analysis (as discussed in more depth in ‘Abusive or Not’ above), good ways to discover systematic abusers, ways to offer additional layers of protection to particularly vulnerable targets, and clear policies for when and how to include external agencies for mental health assistance (in the case of suicide prevention) or law enforcement (serious threats, terrorism, etc).

On top of that, post-moderation needs a solid set of metrics, measuring and prescribing how quickly reported tweets are dealt with, whether appropriate actions were taken, and as potential escalation points in case a user feels that they weren’t dealt with fairly in the process.

Step 4 — Implement better preventative moderation

The final step of this is to get ahead of the curve: My hastily-assembled abuse bot was able to determine conclusively whether something was or wasn’t abusive in 30% of cases.

Twitter has access both to the raw data and better coders than me (just my little joke — I’m a data-enabled journalist at best, and no sane person would let me anywhere near a live code base), and I suspect that a team at Twitter could get up to 70–80% correct, conclusive determination as to whether a particular tweet is abusive or not. What is done from there goes back to the policy question above, but even if you skim off the 10% most abusive tweets (either by taking automatic action, or by sending them into a separate moderation queue for manual moderation), that makes Twitter a significantly nicer place to be.

One way to do this would be to have switch under your Safety settings, much like the quality filter that verified users have had access to for a year:

Step 5 — Close the feedback loop

Of course, the final thing to do is to close the feedback loop.

There are too many examples of users who are trying to work within the current system who are showing off blatant cases of abuse that, even after using Twitter’s reporting functionality, are met with either an absence of action, or what appears to be obviously wrong decisions to keep instances of heinous abuse live on the platform.

Not only is that embarrassing to Twitter, it means that the most vulnerable users on Twitter are in a semi-permanent state of wondering whether it’s time to leave the platform.

Of course, not all posts that are reported should be deleted; that is, in itself, an avenue of abuse potential; but a user should at least have the opportunity to be heard, and receive an explanation for why a particular post is not against the policies that are in place. From there, if it seems that a policy is wrong, inaccurate, or incomplete (it happens…), there should be a process for refining and adjusting the policies to match the intended outcomes.

It won’t be easy, but it must be done.

Abuse, harassment, impersonation, bullying, threats, terrorism, doxxing, illegal pornographic content… There is no shortage of challenges Twitter is facing on the content side.

Solving the problems is not going to be easy, but I feel that if Twitter wants to be the place where the global conversation continues to happen, it needs to be a place where people can discuss, share, and explore together. They need to be able to do so safely, with an explicit agreement for what the parameters are of how you interact. Ideally, this ‘agreement’ should include provisions so groups of friends who do talk to each other largely in explicit language should be able to continue to do so.

Having said that, I’m all for spirited discussions and passionate opinions, but there is no doubt in my mind that on my Twitter, there is no space for threats, abuse, and harassment.

It’s time for a social network to step up and show the world how you can be the venue for a global conversation on every topic under the sun, without alienating the voices belonging to people who are less inclined to accept that ‘abuse is just part of it’.

I do hope that Twitter takes a plunge, and decides to go through the undoubtedly painful process of becoming that social network; if not Twitter, then who?

Try the bot yourself

By popular demand, I’ve created a public version of the bot. It’s very limited compared to the bot I used myself (it doesn’t store info between sessions etc). You can try it out here, if you want.

The broad idea or issue that a message deals with.

The goal or objective that the creator of a message is trying to achieve by communicating that message.

The unique viewpoint, new information, or interesting take on a topic.

A diagram that depicts suggested relationships between concepts.

The systematic investigation into and study of materials and sources in order to establish facts and reach new conclusions.

A beginning section which states the purpose and goals of the following writing, generally followed by the body and conclusion. The introduction typically describes the scope of the document and gives the brief explanation or summary of the document.

The main idea, point, or claim of a written work. Plural: theses.

The last paragraph in an academic essay that generally summarizes the essay, presents the main idea of the essay, or gives an overall solution to a problem or argument given in the essay.

The manner of expressing thought in language characteristic of an individual, period, school, or nation.

The general feeling or attitude of a piece of writing.

Special words or expressions that are used by a particular profession or group and are difficult for others to understand.