7.1.4 Research Paper

Introduction

Dating back to Western Europe in the 1600s, the Illuminati began as a small, secret organization seeking to change the influence of religion and government. Today, however, the perception of the Illuminati is larger-than-life and entirely fictitious. Rather than living through a few, select members as it once did, this society now lives in the minds of conspiracy theorists and is buffered through pop culture. Therefore, looking through the disciplinary lens of history is invaluable in this case to discover how and why the belief in the Illuminati has evolved in such an unusual way. It has become increasingly clear that belief in the Illuminati, like all conspiracy theories, must have a psychological rather than physical meaning behind it. With long-lasting effects of mistrust in the government, isolation, and alienation from the greater portion of society, the disciplinary lens of psychology is the next to be considered. The last disciplinary lens is that of Sociology, to delve into why the Illuminati conspiracy, along with many other similar theories, has such deep ties with Anti-Semitism and religious prejudice.

For a now-fictional concept, the Illuminati has a lot of ground to cover. So how and why did the organization even begin in the first place?

History

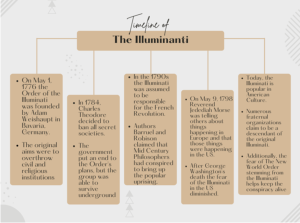

The Illuminati is a name given to many groups, both fictitious and real. On May 1, 1776, the Order of the Illuminati was founded by Adam Weishaupt in Bavaria, Germany. Weishaupt, known as Spartacus by members of the group, was a former Jesuit and law professor at the University of Ingolstadt (Britannica, 2022). The original organization “aimed to overthrow civil and religious institutions with the claim that ends justify the means,” while also keeping a charitable and philanthropic image in the public eye (O’Brien, 2003, p. 598). Nearly ten years following the formation of the Illuminati, the group had expanded from five members to almost three thousand (Waterman, 2005, p. 17).

By the late 1870’s, the Bavarian government seized papers belonging to the Illuminati. This was an attempt to eliminate the Order and secret societies as a whole (Waterman, 2005, p. 17). This strong action against secret societies quickly put an end to the Order’s plans, but the idea of the group’s secretive existence has “fueled conservative theories from the 1780s to the present” (Waterman, 2005, p.17). The Order was therefore forced to operate in secret because its members’ names had been revealed and were accused of various anti-religious acts.

In the 1790s, an anti-Illuminati crusade formed in response to the French Revolution. French Jesuit, Abbe Barruel, published an exposé accusing the Illuminati of being directly responsible for the French Revolution. Following Barruel’s exposé, American professor John Robison wrote a publication expressing similar views. Both authors implied that the Illuminati were still operating secretively and supported the conservative view that mid-century philosophers, such as Voltaire, Montesquieu, and Rousseau, conspired to provoke the popular uprising. According to Barruel and Robison, the mid-century philosophers were “not only responsible for the overthrow of religion and government in France, but also for conspiring to infiltrate and seize control of all the governments in the world” (Waterman, 2005, p.17). This included the emerging United States government. Thus, fear of the Illuminati was quickly instilled in the minds of the American people.

While the Illuminati existed in the past, there is no evidence that it exists today. Recently, however, the Illuminati has begun to reappear online. It has gained traction throughout popular culture and is featured in television shows, movies, and YouTube videos. In addition to the presence of the Illuminati in entertainment media, there are also many recent scammers and websites acting as the Illuminati. These misleading groups promise people money, housing, celebrity interviews, and more (Bitdefender, 2023). The name has become merely another well-known word used to fulfill the purposes of whomever may want to use it. Numerous fraternal organizations claim to be a descendant of the original Bavarian Illuminati, while also openly using the name “Illuminati” as a part of their organization’s title. However, there is no evidence to prove that any of these organizations have ties to the historic Order. All in all, this interesting and relatively isolated circumstance in history seems to have no further proof of its continuation today.

Psychology

If there is no logical reason to believe in the Illuminati, why does it currently have such a presence in our society, and what compels people to hold onto their belief so fervently? The first reason is one that all conspiracies share. Belief in the Illuminati (or any conspiracy) provides an explanation for some idea or event that is “confusing or threatening to self-esteem”, or in other words, is out of one’s control, reports Sophia Galer in “The accidental invention of the Illuminati conspiracy” (Galer, 2020). This explanation involves some evil power, usually the government, being responsible for a large-scale coverup of some kind. Angelo Fasce explains this type of explanation, an idea called conspiracy ideation, which promotes a “threatening, non-random, and immoral worldview”, and is a key aspect of all conspiracies (Fasce, 2019, pg.8). Naturally, conspiracy ideation often gives rise to a very strong political stance, and conspirators more often than not become unwavering in their beliefs, considering themselves to be an enlightened minority. The irony here is that they refuse to acknowledge any other point of view. There are psychological reasons behind the belief in events or ideas that reject the standard explanation behind them. Social exclusion creates a feeling of meaninglessness within, and the search for meaning can often lead people to notice patterns in randomness. Isolation leads to individual distrust in society, fear that the world is out to get them, and a worldview that shuts out change in any form. There are many cognitive contributions behind believing in conspiracies, and more specifically believing in secret societies like the Illuminati.

The recent COVID-19 pandemic has had an extreme effect on numerous individuals due to the quarantine period that occurred alongside the virus. This was a time of increased social isolation for many, and “societies have also witnessed the spread of other viral phenomena like misinformation, conspiracy theories, and general mass suspicions about what is really going on” (De Coninck et al., 2021). Conspiracy theories and their associated beliefs are a way of coping to satisfy thwarted needs and fulfill a lost sensation of significance. Nevertheless, these kinds of subsistence are not expected to truly satisfy the basic needs; they can only temporarily compensate for them. A study published in Frontiers in Psychology shows how empirical data suggests that conspiracy theories may “cultivate the thwarting of the basic needs, creating a feedback loop in which the person is further reinforced to support and expand their beliefs in conspiracy theories” (Leonard and Philippe, 2021). It was also mentioned how the exposure to conspiracy theories decreases the feelings of control and autonomy by increasing one’s perception of powerlessness. The concept of Herd Mentality applies when a good portion of society begins to tout the same ideas. When one has an irrational belief and finds others that support their belief, it helps to satisfy the psychological craving of loneliness and reinforces the idea that they are correct. However, conspiracies cannot completely relieve the psychological distress of loneliness as increasing practice in such wild fantasies will generally increase the amount of distrust in society as a whole. Social isolation is both a cause and effect of believing in conspiracy theories and secret societies like the Illuminati.

Much of the supposed proof that is behind the current existence of the Illuminati is popular culture– videos, photos, the news, celebrity behavior, etc. When people see these obscure sources of information, they will often find a way to render the “evidence” to support their beliefs, which is a form of confirmation bias.

Conspiracy theories in general are associated with a range of negative consequences, mostly stemming from violence. An article written by Karen Douglas from Cambridge University Press evaluated several different studies and concluded that people who were predisposed to conspiracy theories were more likely than others to agree that “violence is sometimes an acceptable way to express disagreement with the government” (Douglas, 2021). Conspiracy theories change people’s attitudes. When initially learning about information from a conspiratorial source rather than a reliable and tested one, it is more than likely that such information will be emotionally held on to and will not receive further exploration. There are also negative consequences involving political engagement and political behavior. It has been found that people who were asked to read anti-government conspiracy theories were less inclined to vote in the next election (Douglas, 2021). Conspiracists have a more relaxed attitude towards gun ownership and are more likely to commit routine crimes. They also tend to indicate that their trust in politics has diminished. Apart from this political apathy, conspiracy theories may also be associated with radicalization and extremism. They have been linked to non-normative political actions such as protests and illegal actions such as occupying buildings. Online extremist groups, both right-wing and left-wing, frequently engage in conspiracy theories. Conspiracy theories may therefore be a “radicalizing multiplier” (Bartlett & Miller, 2010) that serves to reinforce ideologies and psychological processes within extremist groups. These relationships tend to be stronger for individuals who have low self-control and are socially isolated. Ironically, however, such distrust in the government may seem to have the opposite effect desired by the individual. Quoting social psychology professor Viren Swami in Sophia Galer’s article, after mentioning how several governments in Asia have used conspiracies to control their people: “In the West, it’s typically been the opposite; (conspiracies) have been the subject of people who lack agency, who lack power, and it’s their lacking of power that gives rise to conspiracy theories to challenge the government…The big change now is that politicians…are starting to use conspiracies to mobilize support” (Galer, 2020).

Sociology

Anti-Semitism is considered a form of racism. This is an act of open discrimination and prejudice against individuals of Jewish descent. Wilhem Marr, a German Publicist, first introduced the term in the late 19th century. “Marr’s intention was to find a term that would explain more persuasively the need to exclude Jews from European secular society than the older religiously based Jew-hatred still popular at the time” (Krondorfer, p. 294). This idea indicated the exclusion of Jews on racial stances. Krondorfer says that the term cannot refer only to the Jewish culture, religion, politics, or racial characteristics, but rather a hatred that encompasses it all.

Several decades after Anti-Semitism was coined, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was published, which is a falsified Jewish text. The book details the fraudulent plan for Jewish world domination and describes the conspiracy to take control of the banking system, political institutions, and the media. This idea of Jewish domination is the epitome of Anti-Semitism. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was used by Adolph Hitler to justify the Holocaust and it is also presently used to condemn individuals of Jewish descent. The origin of the book is unknown; however, it is believed that it had been “created by a governing body of the Jews” (Dice, Pg. 25). Despite the lack of evidence that backs up the validity of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, it became one of the most notable Anti-Semitic publications.

An example found in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion is the plan to control the banking system. The Rothschild family is a famous household from the 1800’s. Mayer Rothschild and his five sons created a “multinational enterprise” and their wealth allowed them to be quite influential. With the Rothschild family being of Jewish descent, they quickly became a target to conspiracy theorists as a “prime example of Jews allegedly using their money to control global financial institutions” (Hudson, 2020). The original five brothers became barons of the Austrian Empire, the first Jewish member of Parliament was a Rothschild, they were bankers of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars, and other members of the family were also able to garner noble status (Hudson, 2020). Due to their success across countries, the Rothschilds fell perfectly into the standard set forward by Anti-Semitic theories. To many, this seems to equate with the notion that the Rothschilds were a part of the Illuminati’s plan to control the world; however, their dedication, diligence, willpower, and determination is what sparked their success.

While it would be delightful to claim that these prejudiced ideas are now long behind modern society, niche internet groups and opinions provide people with a way to hide behind their harmful beliefs. To keep themselves relevant, one of the primary functions social media platforms use are algorithms that function as “filter bubbles” for the purpose of creating personalized “ecosystems of information” (Fasce, 2019, pg. 9). These filters, referred to as a cycle of “expression-response-satisfaction” and “expression-response-dissatisfaction” create digital boundaries that essentially restrict what people can see and learn about the world through these platforms based on what sort of content they have shown to prefer or not prefer in the past. From an entertainment aspect, this is perfectly logical, but when social media only provides certain types of controversial content consistently, it becomes easy to forget there are other points of view not being accurately represented. This is especially true since social media is notorious for amplifying extreme views, fake news, and emotionally appealing content more efficiently than moderate, factual information. When it comes to conspiracies, especially the Illuminati, people often only see their conspiratorial points of view online and interact with many more people who think alike online: leading them to have stronger conspiratorial beliefs. As the old saying goes, where there is smoke there is fire, and these groups are often coupled with racist and prejudiced views. According to a study done by the AJC, “69% of Jews surveyed reported they have experienced antisemitism online, either as a target or by seeing antisemitic content” (“American Jewish Committee Urges Social Media Firms to Confront Antisemitism on Platforms”, 2023).

The connection between the Illuminati and Anti-Semitic views is detrimental to the function of a unified society. When two parties, such as the Illuminati and Jewish people, are linked together negatively, it encourages hate and distrust between those involved. The Illuminati and its connection to Jewish people are both examples of pseudo-theory promotion. When individuals are advocating that a religion has been corrupted with the intention for world domination, they are presenting an idea that relies on anecdotal evidence. For something to be relied upon and trusted, it requires substantial evidence, which is certainly not present in relation to Jewish ties with the Illuminati.

Conclusion

Although the Illuminati, as it was originally, is a long-gone relic of history, there still exists much consternation and conjecture about the nature of the society’s influence. One may even say that the modern-day members of the Illuminati are not, as suspected, powerful government officials or planted celebrities, but rather the people who still cling to the idea and live in fear of such imaginary forces. In many ways, the Illuminati conspiracy has severely depleted many sociological, psychological, and trusting mannerisms and traits of its current members. This skepticism and imaginary persecution can easily lead to a feeling of isolation, which is often the natural response to suspecting that the world has it out for like-minded people. Through changes across time and societal means, the views and beliefs in the Illuminati have altered to a more pop-culture and governmental-focused perspective, but the effects and negative consequences still lay. In some ways, it almost seems as though the Illuminati is merely a cover story for the Antisemitism, suspicion, and governmental fear that falls within its bounds. The name and meaning of this influential group started with an underground organization, and now continues buffered only by terror and hatred.

References

American Jewish Committee urges social media firms to confront antisemitism on platforms. AJC. (2023, February 21). https://www.ajc.org/news/american-jewish-committee-urges-social-media-firms-to-confront-antisemitism-on-platforms

Bartlett, J., & Miller, C. (2010). The power of Unreason: conspiracy theories, extremism and counter-terrorism. Demos. https://demos.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/Conspiracy_theories_paper.pdf

Bebergal, P. (2014, December 16). Decoding those Lingering Jay-Z Illuminati Rumors. Vulture. https://www.vulture.com/2014/12/jay-z-illuminati-satan.html

Bitdefender. (2023, June 1). The Anatomy of Illuminati Scams: We spoke to the grand masters so you don’t have to. Hot for Security. https://www.bitdefender.com/blog/hotforsecurity/the-anatomy-of-illuminati-scams-we-spoke-to-the-grand-masters-so-you-dont-have-to/

Bouvier, J. (2023, November 3). Rothschild family. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Rothschild-family

Conway O’Brien, J. (2003). The good society: The Illuminated, Karl Marx and Adam Smith. International Journal of Social Economics, 30(5), 598–612. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068290310471862

De Coninck, D., Frissen, T., Matthijs, K., d’Haenens, L., Lits, G., Champagne-Poirier, O., Carignan, M.-E., David, M. D., Pignard-Cheynel, N., Salerno, S., & Généreux, M. (2021, March 26). Beliefs in conspiracy theories and misinformation about COVID-19: Comparative perspectives on the role of anxiety, depression and exposure to and trust in information sources. Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646394/full

Dice, M. (2009). The Illuminati: Facts & fiction. Google Books. https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Illuminati.html?id=GeXBzJBJe1wC

Douglas, K. M. (2021, February 22). Are conspiracy theories harmless?: The Spanish Journal of Psychology. Cambridge Core. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/spanish-journal-of-psychology/article/are-conspiracy-theories-harmless/FA0A9D612CC82B02F91AAC2439B4A2FB

Fasce, A. (2020, June 30). The upsurge of irrationality: Post-truth politics for a polarised world. Semantic Scholar. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-upsurge-of-irrationality%3A-post-truth-politics-a-Fasce/14014b1a3658288be452ff1dd69a5f0f8c33e82d

Galer, S. (2022, February 24). How the Illuminati was invented. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20170809-the-accidental-invention-of-the-illuminati-conspiracy

Hansson, S. O. (2017, May 31). “Science Denial as a Form of Pseudoscience,” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0039368116300681.

Hudson, M. (2020). Where do Anti-Semitic conspiracy theories about the Rothschild family come from?. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/story/where-do-anti-semitic-conspiracy-theories-about-the-rothschild-family-come-from

Krishnan, N. (2019, February 11). The Illuminati Conspiracy Theory. The Psychology of Extraordinary Beliefs. https://u.osu.edu/vanzandt/2019/02/11/the-illuminati-conspiracy-theory-2/

Krondorfer, B. (2015). Introduction: Anti‐semitism and islamophobia. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26605697

Leonard, M.-J., & Philippe, F. L. (2021, June 28). Conspiracy theories: A public health concern and how to address it. Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.682931/full

McIlhany, W. (2009, June 12). A primer on the Illuminati. The New American. https://thenewamerican.com/us/culture/history/a-primer-on-the-illuminati/

Saltarelli, K. (2015, June 8). 11 unbelievable conspiracy theories that were actually true. HowStuffWorks. https://history.howstuffworks.com/history-vs-myth/11-unbelievable-conspiracy-theories-that-were-actually-true.htm

Van Cleave, M. (2016). Introduction to logic and critical thinking \. Open Textbook Library.

Waterman, B. (2005, January). The Bavarian Illuminati, the early American novel, and histories of the public sphere. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3491620.pdf