Learning Objectives

- Identify why social workers might use single-subjects design

- Describe the two stages of single-subjects design

Single-subjects design is distinct from other research methodologies in that, as its name indicates, only one person is being studied. Since social work often involves one-on-one practice, single-subjects designs are often used by social workers to ensure that their interventions are having a positive effect. While the results will not be generalizable, they do provide important insight into the effectiveness of clinical interventions. Single-subjects designs involve repeated measurements over time, usually in two stages.

The baseline stage is the period of time before the intervention starts. During the baseline stage, a social worker would be looking for a pattern to emerge. For example, a person with substance misuse issues may binge drink on the weekends but cut down their drinking during the work week. A substance misuse social worker may ask a client to record their alcohol intake, and they would probably notice this pattern after a few weeks. Ideally, social workers would start measuring a client for a little while before starting their intervention to discover this pattern naturally. Unfortunately, that may be impractical or unethical to do in practice. A retrospective baseline can be attained by asking the client to recollect a few weeks before the intervention started, though it is likely to be less reliable than a baseline recorded in real time. The baseline is important because unlike in experimental design, there is no control group. Thus, we must see if our intervention is effective by comparing the client before and during treatment.

The next stage is the treatment stage, and it refers to the time in which the treatment is administered by the social worker. Repeated measurements are taken during this stage to see if your treatment is having the intended effect. But what exactly are we measuring in single-subjects design? Continuing with our example of substance misuse, we could measure the number of drinks that our client consumes in a night. In this example, we should assume that the client’s binge drinking is identified as a problem by the client and it’s a part of their treatment plan. By looking at the number of drinks they consume, we could evaluate the level of alcohol consumption— for example, by looking at how close they are to dangerously high levels of intoxication. We could look for trends— perhaps the client is in crisis and their drinking getting worse by the day. We may also look at variability, like when their binge drinking is most profound—on weekends or when they are around certain family members.

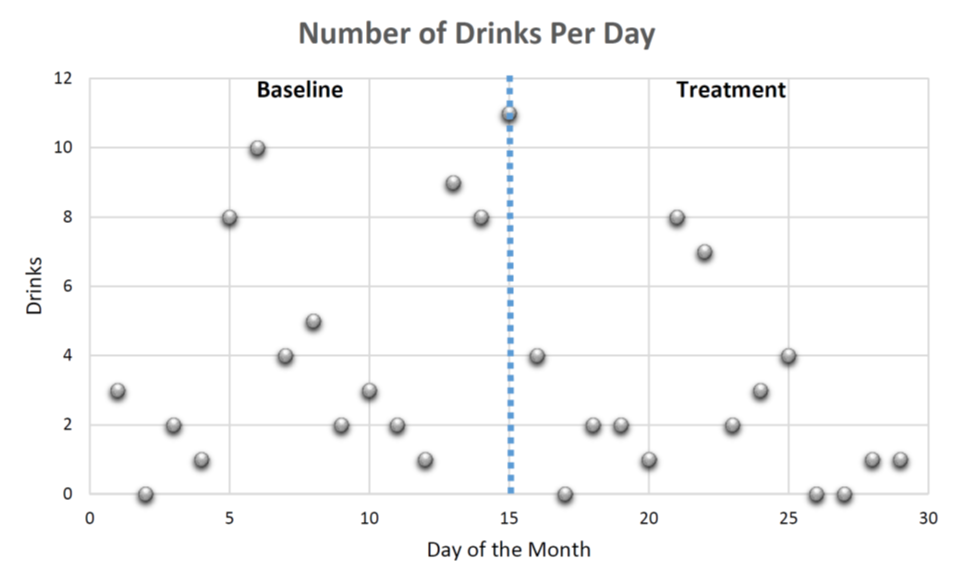

Generally, the measure is graphed on an X-Y axis like in Figure 15.1. The x-axis is time, as measured in days. The y-axis is the problem we’re trying to change, our dependent variable. In Figure 15.1 below, the y-axis is our client’s count of the number of drinks per day. Our client did not receive any treatment for the first fourteen days, or two weeks. This is the baseline phase, and we can see the pattern emerge in their drinking. They drink to excess on the weekends. Once our treatment has started on day 15, we can see that pattern decrease somewhat, indicating the treatment is starting to work.

By visualizing the data in this way, we can identify patterns for analysis. For example, it looks like our client engages in binge drinking on a weekly basis. Days 5-6, 12-15, and 21-22 all contain the highest number of drinks. Their level of drinking is more moderate on other days, though the total amount is still worrying. This is known as a trend in the data. Our client’s baseline trend is curvilinear, going up for a few days and dipping back down. The baseline phase should extend until a trend is evident. Establishing a trend can prove difficult in clients whose behaviors vary widely. The curvilinear trend reappears in the treatment stage once but does not appear again as expected. This suggests that our intervention may have stopped the client from binging again, though certainly further measurement is warranted to make sure.

Although it may be difficult to see visually, if you do the math, our client consumed about one less drink per day after we started the treatment. On average, the client consumed 3.65 drinks per day in the baseline phase and 2.64 drinks in the treatment phase. While this decrease is encouraging, our client is still engaging in excessive use of alcohol. We may want to further refine and target our intervention. If we were to begin a new course of treatment or add a new dimension to our existing treatment, we would be executing a multiple treatment design. For example, let’s say we revised our treatment on day 30. Our graphing would continue as before, but with another vertical line on day 30, indicating a new treatment began. Another option would be to withdraw our treatment for fifteen days and continue to measure the client, reestablishing a baseline. If the client continues to improve after the treatment is withdrawn, then it is likely to have lasting effects. While I don’t think this is advisable for our client, given their problematic use and the short time in treatment, it may make sense after a period of sobriety has been achieved.

Single-subjects designs, much like evaluation research in the previous section, are used to demonstrate that social work intervention has its intended effects. There was a time in the history of social work in which single-subjects designs were thought to be a method of creating a new scientific foundation for social work (Kirk & Reid, 2002). [1] Social workers were to be practitioner-researchers whose practice would empirically test various interventions, ensure competence and effective practice, and demonstrate measurable change to clients. Most social workers do not receive extensive training in single-subjects designs. More importantly, practitioners may be too overworked or undercompensated to conduct data collection and analysis, given that it is not a reimbursable activity for insurance companies. This is in contrast to evaluation research, for which data collection and analysis are incorporated as part of the grant funding system. For this reason, the practitioner-researcher divide has been bridged mostly through evaluation research and partnerships between practitioners and academic researchers. Agency administrators partner with researchers to implement and test academic ideas in the real-world.

Single-subjects designs are most compatible with clinical modalities such as cognitive-behavioral therapy which incorporate client self-monitoring, clinician data analysis, and quantitative measurement as parts of treatment. In this therapeutic model, it is routine to track behaviors such as the number of intrusive thoughts experienced between counseling sessions. Moreover, practitioners spend time each session reviewing changes in patterns during the therapeutic process, using it to evaluate and fine-tune the therapeutic approach. Although researchers have used single-subjects designs with less positivist therapies, such as narrative therapy, the single-subjects design is generally used in therapies with more quantifiable outcomes. The results of single-subjects studies are not generalizable to the overall population, but they help ensure that social workers are not providing useless or counterproductive interventions to their clients.

Key Takeaways

- Social workers conduct single-subjects research designs to make sure their interventions are effective.

- Single-subjects designs use repeated measures before and during treatment to assess the effectiveness of an intervention.

- Single-subjects designs use a graphical representation of numerical data to look for patterns.

Glossary

Baseline stage- the period of time before the intervention starts

Multiple treatment design- beginning a new course of treatment or adding a new dimension to an existing treatment

Treatment stage- the time in which the treatment is administered by the social worker

Trend- a pattern in the data of a single-subjects design

Image attributions

counseling by tiyowprasetyo CC-0

- Kirk, S. A. & Reid, W. J. (2002). Science and social work: A critical appraisal. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ↵