A major difference between social work and many other disciplines is our profession’s emphasis on intervening to help create or influence change. Social workers go beyond trying to understand social issues, social problems, social phenomena, and diverse populations: we also apply this knowledge to tackle social problems and promote social justice. This chapter provides a context for understanding whether the things we do in social work practice are helpful. We begin with a brief review of major concepts learned in the first course that have direct application to the learning objectives of this second course, SW 591.

In this chapter you will:

- Revisit key concepts from SW 590 related to aims of SW591;

- Explore basic concepts about social work intervention;

- Discover how empirical evidence fits into social work practice.

Review of Key Concepts

It is impossible to rehash all the important material from our previous course. However, it is helpful to revisit a few concepts with great relevance to our current course:

- The first important set of concepts that carry over from our previous course is the role played by empirical evidence and critical thinking in the social work profession. This theme carries through our current course. We will see, once again, the importance of this form of knowledge for informing professional practice decisions, as well as for evaluating intervention impact.

- Among the topics explored in SW590 was the set of relevant standards in our professional Code of Ethics. The points concerning the social workers’ Code of Ethics continue to provide an important context for understanding and appreciating the role played by research and evidence in understanding social work intervention.

- You learned about the ethical and responsible conduct of research, including what is discussed in the NASW Code of Ethics. The points from Standard 5.01 (d) through (q) all continue to have great relevance as we explore intervention research in our current course.

- The role of theory in developing social work knowledge represented another key topic from SW 590 . As you will see in this course, theory continues to play a significant role as we think about social work intervention.

- Another topic that retains its relevance between our previous and current courses involves developing a research question. While this content is relevant to designing and assessing research for and about social work intervention, skills related to “causal” questions are relevant for practice, program, and policy evaluation, as well.

- A great deal of emphasis in our current course is dedicated to locating and assessing evidence available in the research literature. What you learned in our earlier course in relation to understanding social work problems and diverse populations (Module 2) is directly applicable to locating and assessing evidence about and to inform social work interventions.

- In our present course, we continue to extend what you learned about research approaches and study designs (Module 3) to the design and implementation of research studies. This includes topics related to study participants and measuring variables of interest (research methodology). As before, we explore how each study design decision is related to the nature of the research questions being addressed.

- Finally, we extend in our current course what you learned about presenting evidence about social work problems and diverse populations to presenting evidence about social work intervention.

In summary, a great deal of content learned about research for understanding social work problems, diverse populations, and social phenomena forms the base for understanding social work intervention. We begin our new voyage by examining what is meant by “social work intervention.”

Understanding Social Work Intervention

When we act to facilitate the process of change, we are engaging in intervention.

“In social work, interventions are intentionally implemented change strategies which aim to impede or eradicate harm, or introduce betterment beyond harm eradication, thus social work intervention encompasses a range of psychotherapies, treatments, and programs. Interventions may be single or complex” (Sundell & Olsson, 2017, p. 1).

The important aspects of this quote are that social work interventions:

- are intentional

- are implemented to create change

- aim to prevent or eliminate harm and/or to promote positive outcomes

- include a range of strategies at the individual, dyad, group, community, policy, and global level

- include strategies with different degrees of simplicity and complexity.

A major defining characteristic of social work intervention is our profession’s practices of intervening at all levels of functioning and social systems—other disciplines or professions generally focus on one or two levels. Here are examples of the multiple ways that social workers intervene at different levels.

Human Biology. Social workers use evidence related to human biology to further their understanding of human behavior, to inform their intervention strategies, and evaluate their intervention efforts. For example, social workers in the maternal and child health arena have a long history of working to improve child development outcomes by intervening to ensure that mothers, infants and young children have access to the basic nutritional and environmental resources necessary for children to grow up healthy and to reach their greatest developmental potential.

Individual. Social workers utilize evidence concerning the “whole” person—biology, psychology, and social world—to assess, intervene, and evaluate interventions with individuals at all ages and stages of life (this combines the biopsychosocial and lifespan perspectives). One branch of “micro” social work practice, called psychiatric social work, addresses the intrapsychic needs of individuals who experience or are at risk of emotional, behavioral, or mental disorders. This is often accomplished through individual counseling and other psychiatric services but may include a host of preventive and environmental interventions, as well.

Interpersonal. Social work professionals are acutely aware of the significance that the social environment plays in human experience, and that individuals function within a system of close interpersonal relationships. Evidence concerning interpersonal relationships is used by social workers both to understand individuals’ experiences and how individuals influence others, as well. This evidence informs their intervention strategies, as well as their evaluation of the interventions they implement. A great deal of social work intervention is aimed at improving functioning in human relationships, including (but not limited to) couples, parents and children, siblings, extended family systems, and other important social groups. For example, one of the Grand Challenges for Social Work (see aaswsw.org) is dedicated to eradicating social isolation and another to stopping family violence—two significant aspects of interpersonal relations.

Communities. Facilitating change within neighborhoods and communities is a long-standing tradition in social work. Community development, community organization, community empowerment, and capacity building are “macro” approaches in which social workers are engaged to improve community members’ well-being. Communities are often self-defined, rather than defined by geography, policy, or other externally imposed authority. Social change efforts that impact larger segments of society often begin with change at the community level. Social workers apply evidence concerning social indicators and other community behavior evidence in planning, implementing, and evaluating intervention at this level.

Organizations and Institutions. Social workers often intervene with organizations, agencies, programs, service delivery systems, and social institutions to effect change both on behalf of the health of the organization and on behalf of the clients these organizations and institutions serve. This type of intervention might be in the form of change agent with the organization or advocacy on behalf of clients affected by the organization. Organizations have both formal and informal systems in operation, and both types have powerful influences on the behavior of individuals in the system. Thus, social workers engage with evidence about individuals, interpersonal relations, and organizational behavior to inform and evaluate their organization and institution level interventions.

Policy. Policy is a form of intervention, and social workers are often engaged in activities that help shape policy decisions or how policy is implemented. Social work interventions include policy established by organizations and social institutions, as well as public policy at the local, regional, state, national, and global/international level. Evidence at all levels is used to engage in policy practice, in terms of shaping, implementing, and evaluating policy that influences the way social workers practice and clients’ lives.

While the breadth of practice domains contributes to the power of social work as a profession, it also contributes to certain challenges. Consider the wide array of practice contexts where social workers intervene:

- child welfare

- corrections/criminal justice systems

- schools and education

- gerontology

- health care systems

- hospice

- intimate partner/domestic/relationship violence

- mental health

- military/veterans affairs

- developmental disabilities

- public health

- substance misuse/addiction

- housing

- food security

- income maintenance/assistance

- workplace/employee assistance

- disaster relief

- community development

- government/policy

- and more…

Now consider the challenge that this diversity creates in terms of the profession’s developing an intervention knowledge base. Some knowledge is relevant across this wide spectrum of levels and settings for social work practice, but a great deal of the knowledge on which social workers depend is specific to a particular social problem, social system, or population. For example, knowledge needed to protect young children from caregiver maltreatment may both overlap and differ from knowledge needed to protect vulnerable older adults and adults with intellectual disabilities from neglect or abuse by their care providers.

Social work intervention is rooted in the principles, values, and ethics of our profession. This includes adopting at least six central perspectives:

- a biopsychosocial perspective

- a lifespan developmental perspective

- a person-in-environment perspective

- a strengths perspective

- an emphasis on client self-determination

- an emphasis on evidence-informed practice.

Where Empirical Evidence Fits into Social Work Practice

In our earlier course, you learned to recognize empirical evidence as one form of knowledge used by social workers in understanding social work problems, diverse populations, and social phenomena. Empirical evidence is equally important to informing and understanding social work interventions.

Briar (1974) identified five expectations regarding the fit between empirical evidence and social work practice. These expectations include:

- “Social work practice is not random but guided by a body of knowledge and skills that are discernible and transmittable and that facilitate attainment of its socially worthwhile and publicly sanctioned goals.

- Social work is responsible for maintaining the institutions necessary to update its knowledge base, to train its practitioners, and to oversee the proper and ethical discharge of its services.

- Practicing as part of a publicly sanctioned profession, social workers must be accountable—to clients, to peers, and to a variety of sanctioning bodies. Accountability is most rudimentarily expressed by a commitment to and a responsibility for demonstrating that practice is effective and efficient. Demonstrating the effectiveness of practice requires evidence that service goals have been achieved and that goal attainment was causally linked to the activities (programs, methods) undertaken to reach the goals. Demonstrating efficient practice also requires evidence that service goals are attained with the least possible cost—in time, money, effort, and client suffering. Thus, in order for social work practice to be accountable it must be subject to scrutiny according to acceptable evidentiary standards.

- A fourth basic premise is that professional knowledge in general, and knowledge that guides intervention in particular, must be tested and supported by empirical evidence obtained and evaluated according to prevailing scientific standards. Such standards must include, at the minimum, an explicit and systematic procedure for defining, gathering, and analyzing relevant evidence.

- Finally, human behavior, individually and in the aggregate, as well as the process of behavior change, is complex and multi-determined. Hence, interventions cannot be viewed as or expected to be uniformly applicable or universally effective. Their effectiveness is likely to vary in relation to the outcomes that are pursued, to the problem and other client characteristics, and to factors of the helping and in vivo situation” (pp. 2-3).

What This Means for Social Work. In summary of Briar’s points, the global questions we always ask are:

- what works,

- for whom does it work, and

- under what conditions does it work?

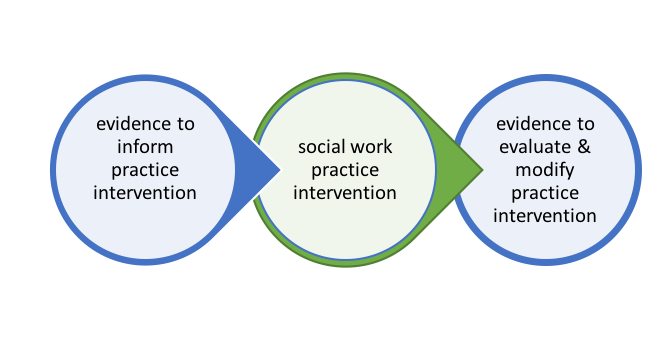

There exist two sides to the evidence “coin” regarding the social work profession. First, social workers seek and utilize evidence to inform our practice decisions. Second, we seek and utilize evidence to evaluate the impact of our intervention efforts and modifying our strategies when indicated by the evidence. Figure 1-1 depicts the relationships between these two facets of social work intervention and evidence.

Figure 1-1. Relationships between social work evidence and intervention

Why this matters so much to our profession was noted in our module introduction: the statement, “good intentions don’t always lead to good results” (Miron, 2015). An example suggested by Briar (1974) was a study of an intensive services intervention provided with the best of intentions to frail elderly clients, but in the end, was associated with a higher mortality rate than the treatment-as-usual condition: 25% compared to 18% (Blenkner, Bloom, & Nielsen, 1971). It was not the services provided by social workers that caused the higher rate of death; the group receiving the intensive services intervention was more likely to be moved to a nursing home setting (34% compared to 20%) than the other group, and this change in placement was likely responsible for the increased mortality. An unintended harmful outcome brought forth by the person trying to help or heal is called an iatrogenic effect of intervention. And, at the very least, we need to be sure that in intervening we are doing no harm.