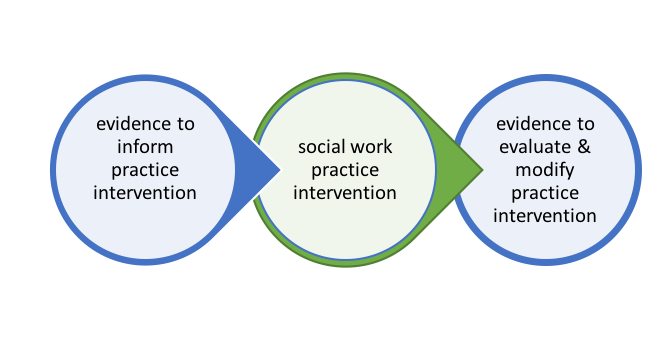

The left-hand side of the evidence-intervention-evidence figure (Figure 1-1) is the focus of this chapter: informing practice decisions with evidence.

This effort could be referred to as addressing “avoidable ignorance” (Gambrill and Gibbs, 2017, p. 73). Selecting an intervention strategy should be guided by evidence of “its potential to achieve the desired goals for clients” (Briar, 1974, p. 2). In this chapter you will learn:

- Definition and elements of evidence-based practice

- How evidence-based practice compares to other types of practice informed by evidence

Defining Evidence-Informed Practice, Evidence-Based Practices, & Evidence-Based Practice in Social Work

As you move through your social work education, you are likely to encounter the term “evidence-based practice” and the expectation that social workers engage in practice based on evidence. On the surface, this seems like a simple concept: social workers engage in practice that is informed by or based on evidence and that evidence evaluating practice is used, as well. The concept of evidence-based practice, however, is considerably more complex and nuanced than it seems on the surface. It is helpful to distinguish between evidence-informed practice, evidence-based practices (note this is pluralized with the letter “s”), and evidence-based practice (not pluralized).

Evidence-Informed Practice. In our earlier course you learned about the ways that social work interventions might be developed based on empirical evidence. Informative evidence included epidemiology, etiology, and prior studies of intervention results: efficacy studies and effectiveness studies. Together, these sources of information, when applied to practice, comprise what is meant by the term evidence-informed practice. The term evidence-informed practices (EIPs) is sometimes used, as well.

Evidence-Based Practices. The concept of evidence-based practices (EBPs) is pretty much what it sounds like: practices based on empirical evidence. When professional practices are based on evidence, practitioners utilize empirical evidence concerning the outcomes of specific intervention approaches as the basis for designing their own interventions. The key to EBPs is that the practices utilized have an evidence base supporting their use, and that they are being implemented with a good deal of fidelity to the interventions as originally studied. The more there is “drift” from the studied intervention, the less relevant the supporting evidence becomes, and the more the practices look to be evidence-informed (EIPs) rather than evidence-based practices (EBPs).

Consider the example of the Duluth Model for a coordinated community response to domestic violence that emerged in the intervention literature during the 1970s and 1980s (see Shepard & Pence,1999). Duluth Model advocates provided a great deal of detail concerning the components of their coordinated community response model, and evidence of its effectiveness in addressing the problem of intimate partner (domestic) violence. Subsequently, many communities adopted the model as representing EBPs, describing themselves as being “Duluth Model” programs. In many cases they integrated only the batterer treatment program approach; many programs incorporated their own tools and local flair into the batterer treatment programs, as well. Unfortunately, the Duluth Model approach to intervening around intimate partner violence included batterer treatment programs alongside a coordinated community response model. What many programs left out was the intensive community organization and empowerment work that was also part of the model—leading to significant changes in local policy, as well as policing and court practices. The evidence supporting implementation of the Duluth Model was not relevant to the truncated intervention approach (batterer treatment only), nor was it relevant when the treatment program was modified with different tools. Communities disappointed that their own outcomes did not match those reported in Duluth were often communities where there had been considerable loss of fidelity to the full model—their practices might or might not have been evidence-informed (EIPs), but they were not the EBPs knows as the Duluth Model. Evidence from the original Duluth Model programs lost its relevance the more the programs changed the shape of their practices—pieces of the puzzle no longer fit together.

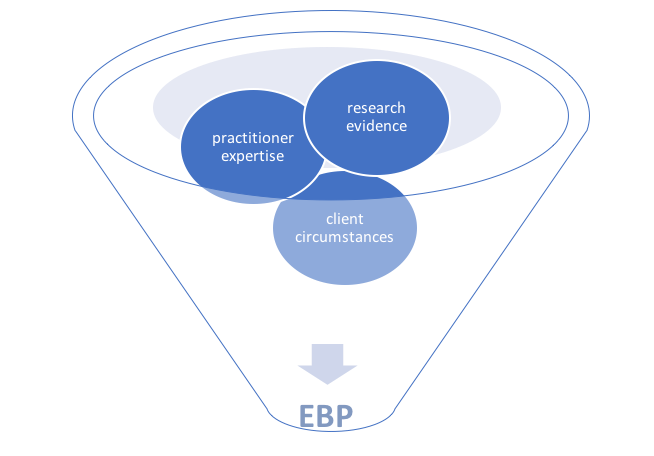

Evidence-Based Practice. Evidence-based practice (EBP), without the “s,” is where further complexity is introduced. EBP is both an ideology and a social work methodology (Gibbs, 2003). As an ideology, EBP involves a commitment to applying the very best available, relevant evidence to problems encountered in practice. “It requires changes in how we locate and integrate research into practice” (Gibbs & Gambrill, 2002, p. 453). This means engaging with evidence at all points of contact with clients, throughout the entire course of the helping relationship. As a methodology, EBP involves applying a very specific process to practice decision-making—assessing what is known and what is unknown about a practice problem (Gambrill & Gibbs, 2017). In the EBP process, empirical evidence is integrated with the practitioner’s professional experience and the client’s (or patient’s) circumstances, values, and preferences (Strauss et al., 2019), as depicted in Figure 2-1. Hence, more sources of knowledge inform practice decisions.

Figure 2-1. The EBP model

Engaging in EBP requires the practitioner to engage in a sequence of six steps which have been modified here from clinical medicine (Strauss et al., 2019) to social work practice at multiple intervention levels (see Gibbs, 2003). Engaging in the EBP process is appropriate when practice situations are uncertain or ambiguous, when routine practice decisions seem inappropriate or inadequate. EBP is about how to approach practice thinking and decision-making in uncertain situations; it is not about what to think or decide.

Step 1: Specifying an answerable practice question.

Step 2: Identifying the best evidence for answering that question.

Step 3: Critically appraising the evidence and its applicability to the question/problem.

Step 4: Integrating results from the critical appraisal with practice expertise and the client’s or client system’s unique circumstances.

Step 5: Taking appropriate actions based on this critical appraisal of evidence.

Step 6: Monitoring and evaluating outcomes of (a) the practice decision/intervention and (b) effectiveness and efficiency of the EBP process (steps 1-5).

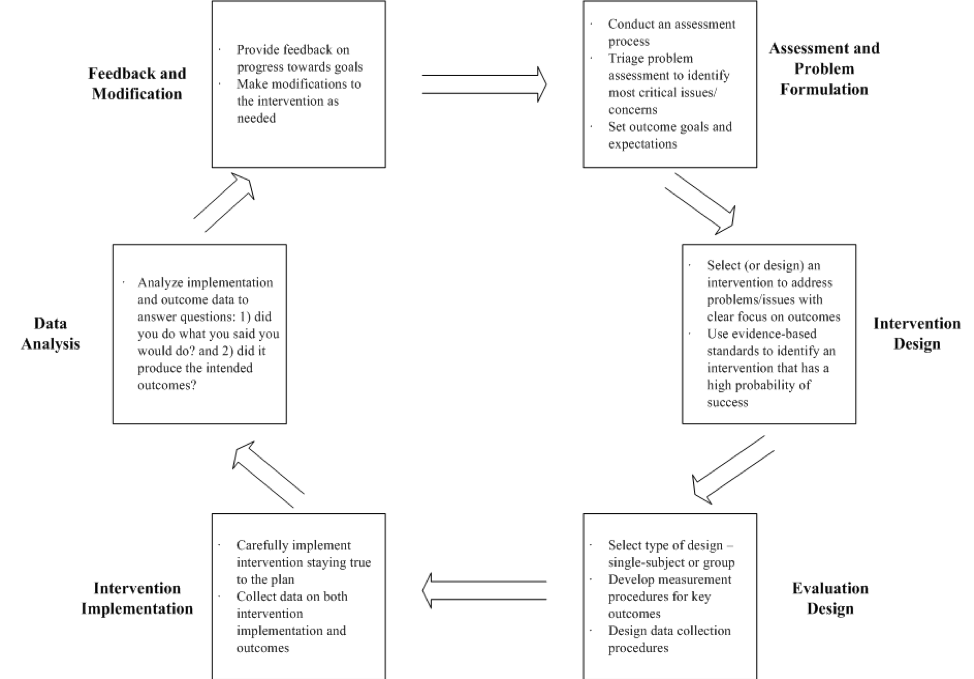

We examine each of these steps in greater detail in Module 2. For now, let’s look at how these steps might fit into the social work problem-solving process overall—regardless of the “micro” to “macro” level of intervening in which a social work is engaged. The Figure 2-2 problem-solving process diagram is provided for us by Dr. Jerry Bean (unpublished), and adjunct instructor with the Ohio State University College of Social Work.

Figure 2-2. Social work problem-solving process and engaging with evidence.

As you can see, engaging with evidence occurs at multiple points in the problem-solving process—from initial assessment of the problem to be addressed, to developing solutions or interventions, to evaluating the impact of those interventions. Good social work interventions are informed by evidence, appropriate for the social work populations to whom they will be delivered (regarding diversity characteristics, past history and experiences), feasible given the resources available (time, skills, space, and other resources), acceptable to the social work professional (in terms of values, beliefs, ethics), and acceptable to the recipient clients.

Critics of Evidence-Based Practice

Before considering criticism of EBP it is important to repeat that the process is not engaged with routine practice matters. EBP is engaged when a practice situation does not fit the typical or routine. For example, a substance abuse treatment program may routinely provide (evidence supported) cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to clients whose goal is to become free of substance misuse. There is no need to engage a search for evidence in this scenario, only to provide clients with their options and the evidence behind them. However, what happens when the social worker encounters a client who experiences significant cognitive limitations resulting from traumatic brain injury (TBI) following an accident, sports-related, or military service injury? The social worker in this scenario could engage in the EBP process to determine the intervention strategies that have the greatest likelihood of successful outcomes for this client experiencing co-occurring problems. However, you should be aware that there are critics who do not entirely embrace the EBP process as a professional standard practice (see Gibbs & Gambrill, 2002).

External constraints. One limitation experienced with strict adherence to the EBP method is concern over a lack of information as to how practitioners account for constraints and opportunities associated with policies or service delivery system structures (Haynes, Devereaux, & Guyatt, 2002). For the most part, the EBP method emphasizes the decision-making process that takes place between the practitioner and the client (or patient). However, practice decisions and decision-making processes are heavily influenced by the context in which they take place. This remains an important practical concern that should be accounted for in both the sphere of practitioner experience and sphere of client circumstances/preferences.

For example, there exists considerable evidence to support sober housing as a desirable placement for individuals in recovery from a substance use disorder. However, there also exist constraints in many communities that include a lack of sufficient sober housing units, sober housing not being adapted for persons with co-occurring mental or behavioral health concerns, and restrictions on eligibility for persons with an incarceration history. Or, for example, a social worker may practice within an agency dedicated to a specific practice philosophy; implementing an innovative approach may not be supported by the agency, regardless of the evidence supporting its use. Some addiction recovery programs, for example, are founded on a philosophy that does not support the use of prescribed medications to support behavioral counseling or therapy (medication assisted therapy, or MAT). A social worker in such a program would be constrained to making a referral to another provider for clients who would benefit from or desire MAT. Thus, practice decisions are influenced by boundaries imposed from the contexts where they happen—the EBP process may not be adaptable to some of these constrains, barriers, or boundaries.

Access to Empirical Evidence. Another possible limitation of the EBP model is that it is heavily dependent on the degree to which empirical evidence might exist related to the practice questions at hand. This issue has several inter-connected parts.

It is difficult and time consuming to locate evidence. The search for relevant evidence can be time and labor intensive. However, degree of difficulty in locating evidence does not excuse a failure to search for evidence. Related arguments reported by Gibbs and Gambrill (2002) include concerns expressed about implementing EBP when practitioners no longer have access to academic libraries at the institutions where they were educated. The counter-argument to this concern: technology has opened access to interacting with a great deal of information, globally.

Being able to search effectively is not the problem it once was; being able to search efficiently is the greater problem—there is often too much information that needs to be sorted and winnowed.

A related argument concerns high caseloads (Gibbs & Gambrill, 2002) and that a practitioner may not be paid for the time spent in this aspect of practice since it is not “face time” spent with clients. Social workers should be advocating for these activities to be reimbursable as client-services. Regardless, our professional code of ethics requires social workers “…to search for practice-related research findings and to share what is found with clients (including nothing)” (Gibbs & Gambrill, 2002, p. 463). It is a professional activity engaged on behalf of, and perhaps with, clients.

Which relates to another of the concerns addressed by Gibbs and Gambrill (2002): EBP as a hinderance to therapeutic alliance or rapport in the practitioner-client relationship. As a counter-argument, this should not be the case if the practitioner engages appropriately in the process. What could be more important to clients than learning about the best alternatives for addressing their concerns? As noted above, the search for evidence can be engage with clients, not only for them. Engaging with evidence is also a professional development activity that may relate to maintaining professional licensure, at least in some states. And, the more you engage in these activities, the more efficient you are likely to become in the process of locating and analyzing this kind of information. It is no longer considered best practice to simply rely on practice traditions (Gibbs & Gambrill, 2002), nor is the search limited to what is available in brick-and-mortar libraries.

Evidence is based on aggregated data, not individuals. This observation means that empirical evidence is typically presented about a group of individuals or cases, not about individuals—and the client or client system with whom the social worker practices is an individual. So, this observation about aggregated data is mostly true, but not necessarily a liability if the information is properly evaluated.

As you may recall from our prior course, social and behavioral science develops theory and evidence based on observations of “samples” made up of individuals who (hopefully) represent the population of interest. The knowledge developed is generalizable from the sample to the population. The disadvantage in aggregating information about a sample of individuals is that we lose specificity about what is going on for any one individual. This loss of individual specificity increases as a function of increasing individual variation (diversity or heterogeneity). So, the criticism is valid up to a point. Evidence from aggregated data gives us some initial good guesses about what to expect, but is not predictive of every individual in the population. Our initial good guesses based on aggregated data improve the more representative the sample is of the population—that the studies included representative diversity. For example, if evidence about the effectiveness of a combined medication/behavioral intervention for substance use disorders is based on a sample of men treated through their Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs), that evidence tells us relatively little about what to expect from the intervention with women or with individuals incarcerated for substance-related offenses—not only might these individuals differ in life circumstances, they may differ in other important ways, such as race/ethnicity, age, and severity of the problem being treated.

The EBP process needs to include attention to representativeness of the samples in the reported studies and how well those studies represent the circumstances of the individual clients with whom we are working. And, the EBP process needs to include an on-going monitoring mechanism so that we can be attuned to points where our individual client experiences diverge from the expected.

Evidence is based on controlled experimental conditions, not real-world conditions. This criticism is partially accurate. Efficacy studies involve carefully controlled experimental conditions that reduce variance as means of enhancing internal validity—the very variability that we see in real-world practice conditions (risking external validity). The rationale is that these approaches ensure that conclusions about the study results accurately reflect the impact of the intervention itself, and not the influence of other explanatory variables. For example, up until the 2000’s, a great deal of breast-cancer research was focused on the population of post-menopausal women. Not only was this the largest group of persons diagnosed with breast cancer, introducing younger, pre-menopausal women and men with breast cancer meant that intervention study results were confounded by these other factors—including them in the studies would make it difficult to determine what was working. However, this also meant that there was little evidence available to inform practice with pre-menopausal women and men who contracted breast cancer. Furthermore, many intervention studies early on were conducted in centers where practitioner-investigators were breast cancer specialists, well-prepared to provide treatment with a high degree of fidelity to the treatment protocols being tested.

For this reason, the next step in the knowledge building process about intervention involves effectiveness studies—testing those efficacy conclusions under more diverse, real-world conditions. As previously noted, this work includes more diverse populations of clients and more diverse practitioners, working under less artificially controlled conditions. Consider, for example, the evolution of Motivational Interviewing (MI), originally developed for addressing alcohol use disorders and now applied across many different physical and behavioral/psychological health conditions (Rubak, Sandbæk, Lauritzen, & Christensen, 2005). When MI was first studied, the supporting evidence was based on intervention provided by practitioners specifically and highly trained in the approach. As evidence for its efficacy and effectiveness expanded, a wider range of practitioners began applying the approach. The originators of MI created a certification process for training practitioners (Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers, or MINT, certification) as a means of reducing variability in its application (enhancing fidelity), but there is no requirement that trainers have this certification (see http://www.motivationalinterviewing.org/for more information). The rarified practice conditions of the initial intervention studies can be equated with a sort of virtual world, somewhat divorced from real-world practice conditions.

The evidence is not necessarily about social work interventions. There should be no disciplinary boundaries placed on the search for evidence related to a particular practice problem—perhaps the relevant practice questions have been tackled by psychology, medicine, nursing, public health, criminal justice, education, occupational therapy, or another profession. We can tap into that potentially rich, diverse knowledge base to inform social work intervention. Many arenas in which social workers practice are interdisciplinary fields, areas such as:

- substance misuse

- gerontology

- developmental disabilities

- corrections

- health care

- education

- mental health

As such, social workers intervene as members of teams where the interventions are not exclusively “social work” interventions.