Introduction

One of the many challenges students face as they begin their college career is how to create and use study materials that ultimately lead to success in both classroom learning and high scores on assignments and exams.

Foremost in having effective study skills is to approach all your learning activities with a growth mindset. A growth mindset means you believe that intelligence is like a muscle—it gets stronger the more it’s used. The more we exercise our brains, the more neural networks are created and the “smarter” we become. We exercise our brain by engaging in studying and practicing what we are learning on a daily basis and having a positive belief about the value of what we are studying.

Working hard, using effective learning strategies, and creating and using study materials improves our ability to learn and ultimately, results in better outcomes and higher academic achievement. The strategies listed in the Creating and Using Study Materials chapter are six of the most effective strategies to use when learning new material, preparing for class activities, and/or studying for an exam.

This video provides information on how to study effectively with six essential skills.

Select the title of each section below to learn more about six of the most effective strategies to explore when creating and using study materials.

3.1 Create Outlines

Many students find that creating a formal outline helps them to identify the most important topics when listening to a lecture or reading a text. You can create a formal outline by using Roman numerals for each new topic. Then, move down a line, indent a few spaces to the right, and use a capital letter for concepts related to the previous topic. Next, move to the following line, indent a few more spaces over, and use an Arabic numeral to add details to support the concept. You can continue to add to a formal outline by following these rules.

The following sample formal outline shows this basic pattern:

- Dogs (main topic–usually general)

- German Shepherd (concept related to the main topic)

- Protection (supporting info about the concept)

- Assertive

- Loyal

- Weimaraner (concept related to the main topic)

- Family-friendly (supporting info about the concept)

- Active

- Healthy

- German Shepherd (concept related to the main topic)

You don’t absolutely have to use formal numerals and letters, but you have to then be careful to indent so you can tell when you move from a higher level topic to the related concepts and then to the supporting information.

The main benefit of an outline is how organized it is. However, you do have to be on your toes when you are taking notes in class to ensure you keep up with the organizational format of the outline. This can be tricky if the lecture or presentation is moving quickly or covering many diverse topics.

You would just continue on with this sort of numbering and indenting format to show the connections between main ideas, concepts, and supporting details. Whatever details you do not capture in your notetaking session, you can add after the lecture as you review your outline.

If you select this strategy for your Study Skills project, create an outline to assist you in studying for each quiz or exam that is assigned in your course(s). Use your course readings–including textbooks, articles, and websites–to assist you in creating your outlines. Identify the main ideas, concepts, and supporting details. Carefully organize your outline to identify higher-level topics, related concepts, and supporting information. Save your outlines so that you can submit them with your project.

3.2 Create Concept Maps

Concept mapping or mind mapping is a notetaking method that appeals to learners who prefer a visual representation of notes. Variations of this method abound, so you may want to look for more versions online, but the basic principles are that you are making connections between main ideas through a graphic depiction; some can get rather elaborate with colors and shapes, but a simple version may be more useful at least to begin. Main ideas can be circled or placed in a box with supporting concepts radiating off these ideas shown with a connecting line and possibly details of the support further radiating off the concepts. You can present your main ideas vertically or horizontally, but turning your paper long-ways, or in landscape mode, may prove helpful as you add more main ideas.

Watch the following video to see examples of concept mapping or mind mapping.

You may be interested in trying visual notetaking or adding pictures to your notes for clarity. Sometimes when you can’t come up with the exact wording to explain something or you’re trying to add information for complex ideas in your notes, sketching a rough image of the idea can help you remember.

According to educator Sherrill Knezel in an article entitled “The Power of Visual Notetaking,” this strategy is effective because “When students use images and text in notetaking, it gives them two different ways to pull up the information, doubling their chances of recall.” Don’t shy away from this creative approach to notetaking just because you believe you aren’t an artist; the images don’t need to be perfect.

If you select this strategy for your Study Skills project, create a concept may to assist you in studying for each quiz or exam that is assigned in your course(s). Use your course readings–including textbooks, articles, and websites–to assist you in creating your concept maps. Identify the main ideas, concepts, and supporting details. Carefully organize your concept map to identify higher-level topics, related concepts, and supporting information. Save your concept maps so that you can submit them with your project.

3.3 Create Cornell Study Sheets

One of the most recognizable notetaking systems is called the Cornell Method, a relatively simple way to take effective notes devised by Cornell University education professor Dr. Walter Pauk in the 1940s.

In this system, you take a standard sheet of paper and complete the following:

- Write the title of the course, the topic or objective, and your name at the top of the page.

- Draw a horizontal line across your paper about one to two inches from the bottom of the page (to create the summary area).

- Draw a vertical line to separate the rest of the page above this bottom area, making the left side about two inches (the recall column) and leaving the biggest area to the right of your vertical line (the notes column).

You may want to make one page and then copy as many pages as you think you’ll need for any particular class, but one advantage of this system is that you can generate the sections quickly. Because you have divided up your page, you may end up using more paper than you would if you were writing on the entire page, but the point is not to keep your notes to as few pages as possible.

The Cornell Method provides you with a well-organized set of notes that will help you study and review your notes as you move through the course. If you are taking notes on your computer, you can still use the Cornell Method in Word or Excel on your own or by using a template someone else created.

The beauty of the Cornell Method is its organized simplicity. Just write on one side of the page (the right-hand notes column)—this will help later when you are reviewing and revising your notes. During your notetaking session, use the notes column to record information over the main points and concepts of the lecture; try to put the ideas into your own words, which will help you not transcribe the speaker’s words verbatim. Skip lines between each idea in this column. You can use bullet points or phrases to convey meaning—we do it all the time in conversation. If you know you will need to expand the notes you are taking in class but don’t have time, you can put reminders directly in the notes by adding and underlining the word expand by the ideas you need to develop more fully.

The main advantage of the Cornell Method is that you are setting yourself up to have organized, workable notes. The neat format helps you move into study-mode without needing to re-copy less organized notes.

If you select this strategy for your Study Skills project, create Cornell Notes to assist you in studying for each quiz or exam that is assigned in your course(s). Set up your Cornell note-taking sheet as described above. Use your course readings–including textbooks, articles, and websites–to assist you in creating your Cornell notes. Identify the main ideas and concepts, and list these concepts on the left side of your note-taking sheet. Take notes on the right side of your note sheet. Finally, write a summary of the source at the bottom of the note sheet. Save your Cornell note sheets so that you can submit them with your project.

Using this strategy will also require you to use the strategy 4.2 Use Cornell Study Sheets in Chapter 4: Studying and Preparing for Tests.

Watch the following video to learn more about the Cornell method:

3.4 Annotate Your Notes

Annotating notes after the initial notetaking session may be one of the most valuable study skills you can master. Whether you are highlighting, underlining, or adding additional notes, you are reinforcing the material in your mind and memory.

Admit it—who can resist highlighting markers? Gone are the days when yellow was the star of the show, and you had to be very careful not to press too firmly for fear of obliterating the words you were attempting to emphasize. Students now have a veritable rainbow of highlighting options and can color-code notes and text passages to their hearts’ content.

The only reason to highlight anything is to draw attention to it, so you can easily pick out that ever-so-important information later for further study or reflection. One problem many students have is not knowing when to stop. If what you need to recall from the passage is a particularly apt and succinct definition of the term important to your discipline, highlighting the entire paragraph is less effective than highlighting just the actual term. If you don’t rein in this tendency to color long passages (possibly in multiple colors) you can end up with a whole page of highlighted text. Ironically, that is no different from a page that is not highlighted at all, so you have wasted your time. Your mantra for highlighting text should be less is more. Always read your text selection first before you start highlighting anything. You need to know what the overall message is before you start placing emphasis by highlighting.

Another way to annotate notes after initial notetaking is underlying significant words or passages. Albeit not quite as much fun as its colorful cousin highlighting, underlining provides precision to your emphasis.

Some people think of annotations as only using a colored highlighter to mark certain words or phrases for emphasis. Actually, annotations can refer to anything you do with a text to enhance it for your particular use (either a printed text, handwritten notes, or other sorts of documents you are using to learn concepts). The annotations may include highlighting passages or vocabulary, defining those unfamiliar terms once you look them up, writing questions in the margin of a book, underlining or circling key terms, or otherwise marking a text for future reference. You can also annotate some electronic texts.

Realistically, you may end up doing all of these types of annotations at different times. We know that repetition in studying and reviewing is critical to learning, so you may come back to the same passage and annotate it separately. These various markings can be invaluable to you as a study guide and as a way to see the evolution of your learning about a topic. If you regularly begin a reading session writing down any questions you may have about the topic of that chapter or section and also write out answers to those questions at the end of the reading selection, you will have a good start to what that chapter covered when you eventually need to study for an exam. At that point, you likely will not have time to reread the entire selection especially if it is a long reading selection, but with strong annotations in conjunction with your class notes, you won’t need to do that. With experience in reading discipline-specific texts and writing essays or taking exams in that field, you will know better what sort of questions to ask in your annotations.

What you have to keep in the front of your mind while you are annotating, especially if you are going to conduct multiple annotation sessions, is to not overdo whatever method you use. Be judicious about what you annotate and how you do it on the page, which means you must be neat about it. Otherwise, you end up with a mess of either color or symbols combined with some cryptic notes that probably took you quite a long time to create, but won’t be worth as much to you as a study aid as they could be. This is simply a waste of time and effort.

If you are annotating your own notes, you can make a habit of using only one side of the paper in class, so that if you need to add more notes later, you could use the other side. You can also add a blank page to your notes before beginning the next class date in your notebook so you’ll end up with extra paper for annotations when you study.

If you select this strategy for your Study Skills project, annotate your notes to assist you in studying for each quiz or exam that is assigned in your course(s). Using the notes you have taken during lectures or while reading, use a different color pen to annotate your notes. Highlight or mark key terms, add definitions for key terms, underline significant words or passages, and add additional notes to make connections between concepts or sources. Save your annotated notes so that you can submit them with your project.

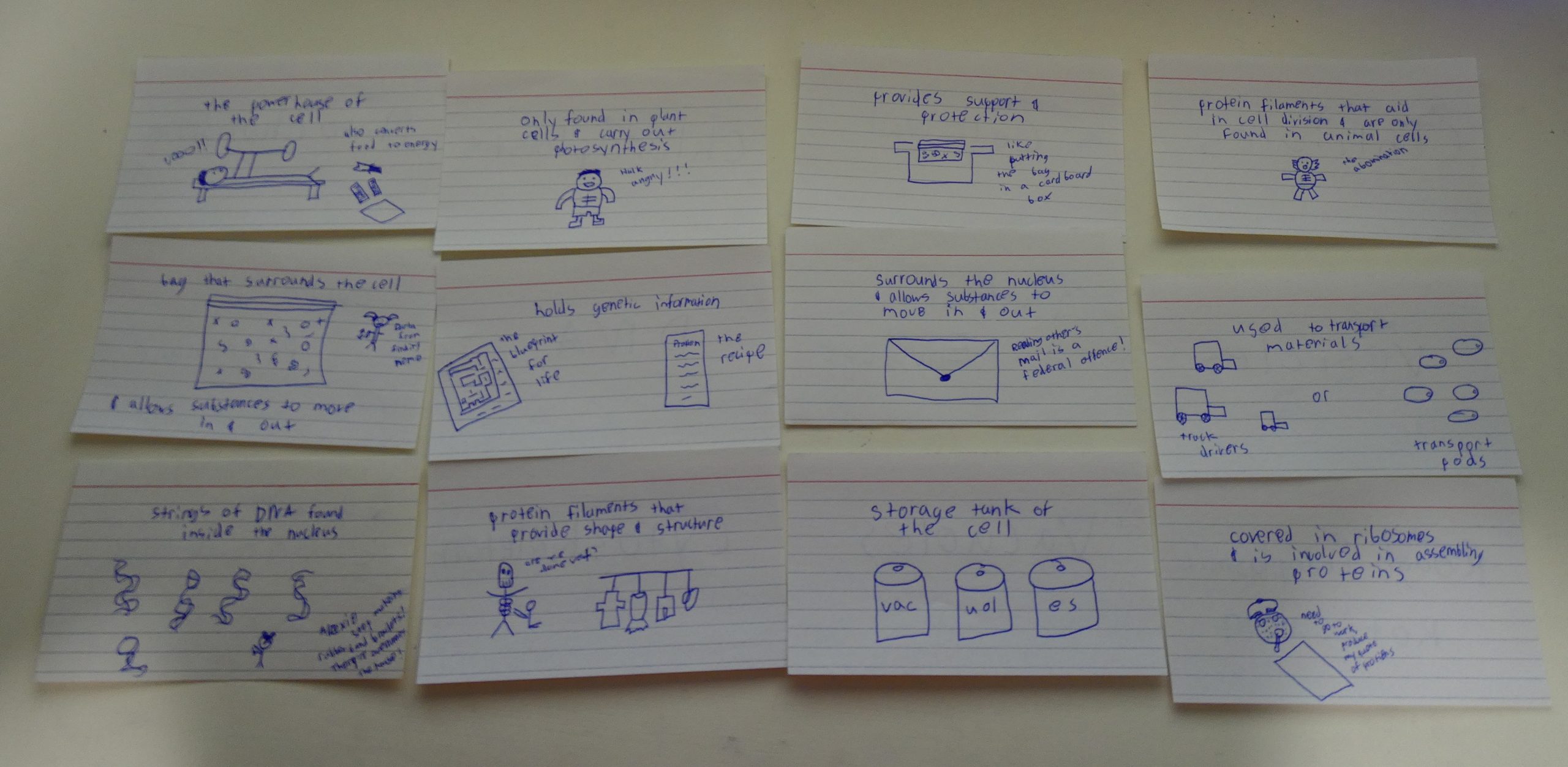

3.5 Create FlashCards

Flashcards are an easy-to-use and versatile study tool. In addition to using them to learn simple facts, you can use them to learn complex information and processes throughout your academic career.

A flashcard is a card with information on both sides. Each flashcard contains a word or question on one side and the definition or meaning of the word or answer to the question on the other. Flashcards are often used to memorize vocabulary, historical dates, formulas, or any content that can be learned via a question-and-answer format.

To maximize your effectiveness in creating flashcards, here are some basic strategies to use:

- Make your own flashcards.

- Mix pictures and words.

- Write only one question per card.

- Use mnemonics—memory aides—whenever possible.

Review the following flashcards created by an FYEX student.

For a more descriptive and in-depth video on how to create and effectively use flashcards to study and learn material, watch the following video:

If you choose this strategy for your Study Skills project, you will need to select at least one of the classes you are taking and create flashcards for this class on a weekly basis. You will need to keep all flashcards you create.

Using this strategy will also require you to use the study strategy 4.3 Study with Flashcards, in Chapter 4: Studying and Preparing for Tests.

3.6 Create Audio Recordings

Have you ever wanted a quicker, easier way to take notes? By creating audio notes you will save time and engage your brain in ways that will produce lasting learning. It’s a simple concept; instead of organizing your notes on paper, you will record them using audio files.

If you select this strategy for your Study Skills project, create weekly voice notes for at least one of your courses. If you have a windows-based computer you can use Voice Recorder. Or you can use your phone (you may need to download an app). Once you have your device set up, you should talk to your device as if it is your ‘study buddy.’ Making the recordings is a great way to evaluate what you know (and what you don’t!), and what you can explain (and what you can’t!). See the accompanying video for more details:

You’ll want to organize your audio files into a folder system and name them by topic or class so you can keep track of them. For your study logs, you can reflect on how you made recordings, how you have felt about learning materials this way, and how useful the voice files have been.

If you choose this strategy, it is strongly recommended that you also choose strategy 4.4 Listen to Self-Made Audio Recordings, in Chapter 4: Studying and Preparing for Tests. That way you will receive credit for both creating and using the audio files.

Licenses and Attribution

Sections 3.1-3.4 were adapted from OpenStax College Success, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/college-success/pages/1-introduction.