According to surveys conducted by the Minneapolis Institute of Arts,[1] visitors are most interested in reading and/or hearing about, in this order:

- Subject (a location, an environment, a person, a concept)

- Content (beauty, personality, repression)

- Function (a memorial, a portrait, worship, education)

- Cultural and historical context (the Italian Renaissance, the Mende people of west Africa, ancient Greece)

- Why the work is considered art and why it’s in the museum

- The artist (statements that pertain to the work, intention and/or style, other related work by the same artist)

- Technique (materials, innovations, specialized methods)

- Economics (commissioned by …, created for sale, created for trade)

Not helpful are

- Unsubstantiated assertions of aesthetic quality or judgments (masterpiece, most profound, naïve, primitive)

- Stylistic development (genre, “influenced by the Mannerists,” Japonisme, in the Gothic style)

- Discussions of art theory (“…critical to the development of Analytic Cubism.” “New class identities.” “Included in the salon of 1866.”)

- Lengthy artists’ biographies

- Provenance (“the painting remained in the Valpinçon family until it was sold to …”)

Consider this sentence, written for the public about the Charleston period room at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts: “The outstanding quality of the rococo carving over the fireplace and the precise classical proportions of the woodwork were probably executed by the English-trained craftsman Ezra Waite, who was responsible for numerous other pre-revolutionary Charleston interiors.” It covers every point on the unhelpful list, leaving the reader to wonder: so what?

A word about using artists’ quotes. Visitors love to hear from artists, or at least that’s what they will tell you. Often I think visitors ask for this information because they know to ask for it. They logically assume that since an artist made it, the artist must be able to explain what it means. People know to ask for what they know about, they can’t ask for what they don’t know about. Confirming my suspicion, Reach Advisors report that in a survey of 40,000 visitors, what museum visitors say they want is different from what they actually found meaning in.[2]

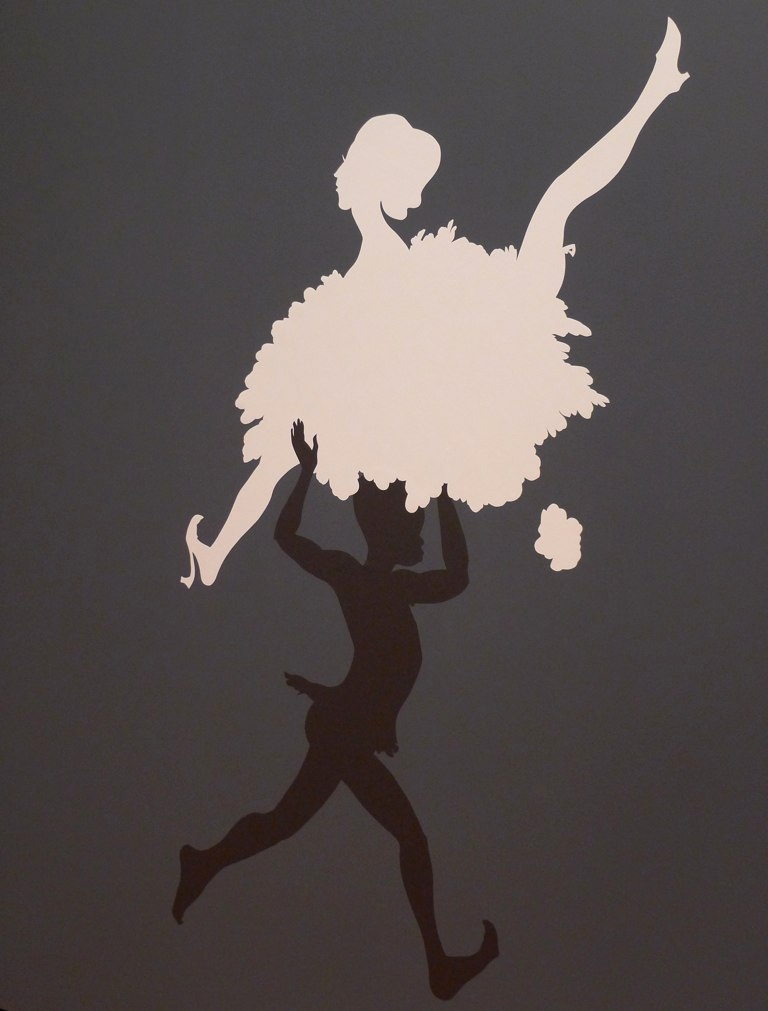

Image courtesy of Lori L. Stalteri, Flickr

“Silhouettes are reductions, and racial stereotypes are also reductions of actual human beings.” – Kara Walker

If you think about it, giving people what they ask for misses the opportunity to use our specialized expertise to amaze and astound them with fascinating new information. Of course if you have an artist’s quote that actually sheds light on a work of art, by all means use it. But not all artists are great at talking or writing about their work. If they were, they might be writers or performers instead of visual artists.

Regarding unsubstantiated assertions of aesthetic quality or judgments, visitors do not like to be told what to think or how to feel. Put the emphasis on unsubstantiated here. If you’d like to tell people that something is a masterpiece, or that a work of art is designed to create discomfort, tell them why and/or how. Taking the time to explain these things moves your writing from unsubstantiated assertions of aesthetic quality or judgments (the not helpful list) into explaining why something is considered art and why the museum decided to display or own it (the helpful list).

- Interpretation at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 34. ↵

- Reach Advisors, "The Lens of Meaningful Experience," accessed September 1, 2013. http://reachadvisors.typepad.com/museum_audience_insight/2012/10/the-lens-of-meaningful-experiences.html ↵