IX. Música dodecafónica

Exemplos de análise – Op. 21 e 24 de Webern

Mark Gotham

Puntos principais

- Cando nos achegamos á música dodecafónica, é fácil caermos no erro de só identificar formas da serie e perder de vista o resto dos parámetros.

- Unha lista das formas da serie que se empregan nunha obra dodecafónica é o mesmo que unha lista de tonalidades nunha obra tonal, é útil, mais non é suficiente para consideralo unha análise.

- Este capítulo trata dúas obras icónicas da primeira música dodecafónica: As op. 21 e 24 de Webern, coa análise de

- detalles técnicos sobre a construción cunha serie simétrica e a composición dalgúns canons, e

- outros asuntos que cómpre considerar sobre a obra, como o significado de “sinfonía” e “concerto” neste contexto.

- Podes obter as partituras en IMSLP.org (Op. 21; Op. 24)

Webern: Symphonie Op. 21 (1928)

Mesmo o propio título da Sinfonía op. 21 de Anton Webern levanta dúbidas. Por que Webern decidiu chamar a isto “sinfonía”? Se pensamos nunha sinfonía como unha obra que ten unhas determinadas relacións entre tonalidades, será que a sinfonía atonal é un oxímoro? Os expertos reaccionaron de forma diversa a esta cuestión:

- “ao escoller os títulos máis tipicamente clásicos, Webern salientou o punto até o cal poden ser relevantes nunha obra en que só permanecen algúns dos principios estruturais” (Whittall 1977, 163).

- “Os seus procedementos formais conteñen poucos aspectos (ou ningún) que sexan comparables aos da sinfonía tradicional” (Taruskin 2010, 728).

Ten en conta estas cuestións ao considerar o resto de aspectos desta obra.

Forma da serie

Exemplo 1. The row of Op. 21, along with the trichordal and hexachordal divisions.

Webern escolle con frecuencia o que poderiamos denominar formas da serie “ben organizadas”, e esta obra non é unha excepción (ver o Exemplo 1). A serie pode ser dividida en dous hexacordos equivalentes que son dúas ocorrencias do mesmo conxunto de clases de altura, que é o conxunto 6-1: metade dunha escala cromática. En resuno, cada unha completa a colección cromática de metade do espazo dodecafónico.

Alén disto, cada un destes hexacordos ten unha aparición do tricordo (013) e outra do (014). No total, as catro células dos tricordos son (013), (014), (014), (013). Estes dous tricordos tamén están unidos pola súa configuración melódica: cada un ten unha terceira (maior ou menor) e un semitón.

Eis a matriz da serie, coa simetría entre P0 e R6 destacada. [1]

| I0 | I9 | I10 | I11 | I7 | I8 | I2 | I1 | I5 | I4 | I3 | I6 | ||

| P0 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | R0 |

| P3 | 0 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 6 | R3 |

| P2 | 11 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 | R2 |

| P1 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 11 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | R1 |

| P5 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 8 | R5 |

| P4 | 1 | 10 | 11 | 0 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 7 | R4 |

| P10 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 8 | 0 | 11 | 10 | 1 | R10 |

| P11 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 2 | R11 |

| P7 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 10 | R7 |

| P8 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 11 | R8 |

| P9 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 0 | R9 |

| P6 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 11 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 9 | R6 |

| RI0 | RI9 | RI10 | RI11 | RI7 | RI8 | RI2 | RI1 | RI5 | RI4 | RI3 | RI6 |

Example 2. Row matrix for Op. 21.

En xeral, a serie é equivalente na súa retrogradación, é dicir, se a interpretamos do revés (R), obtemos unha versión trasposta da orixinal (P). Cando temos equivalencias deste tipo, xa non hai 48 formas diferentes da serie. Aquí temos pares de series equivalentes, e por tanto hai 24 formas diferentes da serie (48 dividido entre 2).

Webern realza esta serie simétrica mediante ao sobrepor o final dunhas formas da serie co inicio da seguinte.

Primeiro movemento

Webern describe o primeiro movemento como oun “canon duplo en movemento contrario”, onde “movemento contrario” significa o mesmo que “inversión”. Poderías pensar na forma xeral como un 𝄆A𝄇𝄆BA′𝄇 , do seguinte xeito:

- A: Do compás 1 até a barra dupla (mm. 23-25).

- B: palíndroma: o c. 35 é o punto medio dos c. 25–43 no clarinete (ou c. 26–42 no cello).

- A′: “recapitulación das series” desde o c. 43 (só as series, non o ritmo motívico, etc.).

Isto lembra á música das sinfonías? As indicacións de repetición e a distribución do material evocan vagamente as repeticións da Exposición e Desenvolvemento–Recapitulación das obras con forma sonata, ou polo menos á forma binaria circular ou reexpositiva.

Eses serían os puntos a favor de considerar que a obra corresponde ao esperable nunha sinfonía. Por outra parte, a simetría pura da serie non acaba aí. Bailey (1991, 96) describiu a sección central como un “tour de force” simétrico, unha proeza da simetría. As recapitulacións e as formas cíclicas son unha cousa, mais na música clásica occidental a utilización metódica da simetría é un concepto asociado ao século XX. Ao falar dunha versión deste asunto con acordes, o compositor británico Jonathan Harvey describiu a estratexia simétrica de mover o baixo cara ao medio como “a nosa revolución” (1982, 2).

Outra consideración importante que contradi a noción dea forma sonata é o uso frecuente de canons en cada sección. Por exemplo, no inicio hai un canon duplo entre varios pares de partes instrumentais (P0 e I0; I8 e P4), deste xeito:

| Forma da serie | Instrumentos | |

|---|---|---|

| Canon 1 | P0 | Trompa 2 → clarinete → cello; elisión co cello → clarinet → trompa 2 |

| I0 | Trompa 1 → clarinete baixo → viola; elisión coa viola → clarinete baixo → trompa 1 | |

| Canon 2 | I8 | Arpa → cello → violín 2 → arpa → trompa 2 → arpa → trompa 2 (…) |

| P4 | Arpa → viola → violín 1 → arpa → trompa 1 → arpa (…) |

Example 3. Canons in the beginning of Op. 21.

Repara nas secuencias de timbres similares nos dous pares. Por exemplo, no primeiro par, temos unha trompa, despois un clarinet, e finalmente un instrumento de corda grave, antes de volver de forma simétrica na mesma orde. Dividir a liña melódica desta forma é un proceso que ás veces é denominado Klangfarbenmelodie (melodía de timbres, ou de “cores sonoras”) e non é algo exclusivo do atonalismo. Mahler adoraba partir melodías deste xeito, por exemplo no exemplo do capítulo dedicado á orquestración (ver Orquestración). Se cadra o exemplo máis icónico de Webern para esta técnica sexa a súa orquestración do Ricercar da Ofrenda musical de J.S. Bach’s.

Segundo movemento: variacións, canon duplo con retrogradación

Co segundo movemento, o título déixao claro: “Variacións” é bastante adecuado, e a estrutura desenvólvese, como é habitual para Webern, en todos os parámetros. Eis unha breve sinopse esquemática do que está a acontecer:

Tema (relacionado coa coda)

- Compases 1–11.

- As frases están divididas en dous grupos de 5,5 + 5,5 compases; o c. 6 é o medio.

- A serie I8 está no clarinete; I2 no resto de partes.

- Emprega combinatoriedade de hexacordos.

Variación 1 (relacionada coa variación 7)

- Compases 11–23; o inicio únese co tema mediate elisión.

- Un canon duplo á negra: o violín 1 vai co cello; o violín 2, coa viola.

- Neses pares, o violín 1 (I3) está relacionado mediante R co violín 2 (I9); a viola (P7) tamén está relacionada mediante R co cello (P1).

- As frases están divididas en 6 + 6 compases; o medio é o c. 17 para os violíns, c. 18 para a viola e o cello. Os violíns intercambian as series, igual que viola e cello.

- O final únese coa variación 2 mediante elisión.

Variación 2 (relacionada coa variación 6)

- Compases 23–34.

- As frases están divididas en 6 + 6 compases (o medio é o c. 29).

- Porén, hai unha terceira parte libre (trompa 1). As notas que coinciden coa pulsación teñen P8, mentres que os contratempos seguen a I7, de modo que as corcheas alternan entre dúas series.

- O final únese coa variación 3 mediante elisión.

Variación 3 (relacionada coa variación 5)

- Compases 34–44.

- As frases están divididas en 1 + 4 + 1 + 4 + 1 compases; o medio é o c. 39.

- Cada parte ten un elemento melódico simétrico, e movemento de semicorcheas.

Variación 4

- Compases 45–55.

- O propio Webern describe esta variación como a metade do movemento.

- As frases están divididas en 5 + 1 + 5; o c. 50 é o medio.

Variación 5 (relacionada coa variación 3)

- Compases 56–67.

- As alturas son presentadas en células de catro notas:

- Viola, cello: [5, 6, 7, 8]

- Violíns: [11, 0, 1, 2]

- Arpa: [3, 4, 10, 9]

- Estas células de catro notas crean un agregado dodecafónico, mais a composición non está baseada en series.

- Cada parte ten un elemento melódico simétrico.

Variación 6 (relacionada coa variación 2)

- Compases 67–77.

- Canon á negra entre clarinete baixo e clarinete.

- Terceira parte libre (trompa 1), a versión retrógrada da parte libre da Variación 2.

- A metade é o c. 73.

Variación 7 (relacionada coa variación 1)

- Compases 78–88.

- Canon triplo: cello/violín 1, viola/violín 2, e clarinete/clarinete baixo. Cada liña dos tres canons ten timbre e ritmo diferenciado.

- A metade é o c. 83.

Coda (relacionada co tema)

- Compases 89–99.

- As frases están divididas en 5,5 + 5,5 compases, e o c. 94 é a metade.

Problemas

Probablemente xa reparaches nalgúns asuntos recorrentes nesta análise. Se cadra o que máis aparece é a simetría que Webern adopta tanto na estrutura interna da serie como na organización dos movementos.

Será que isto a torna completamente moderna? Ou será que a simetría contribúe para unha nova música teololóxica (orientada para un fin), que é típica ao menos desde Beethoven? Que pensamos sobre do we feel about the occasional direct historical precedent like the entirely symmetrical Minuet and Trio in Haydn’s 47th symphony?

O máis importante é determinarmos cal é o efecto desta simetría na audición. Sorprendeute a cita de Harvey de antes? Ao final, hai razóns acústicas que fixeron que historicamente as composicións tendan a construír acordes desde o baixo real. Do mesmo xeito, non somos capaces realmente de “escoitar” a simetría lineal (escoitar do revés) do mesmo xeito que podemos ver a simetría nun cadro, por exemplo. Dito isto, Webern esforzouse moito (polo menos nalgúns fragmentos) por deixar clara a estrutura da obra. Para Cook, “todo [nesta Symphonie] está deseñado para facer que a serie sexa audible” (1987, 295).

Quizá deberiamos considerar que esta é outra sinfonía do século XX, coas súas particularidades. Pensa nas moitas sinfonías de Stravinsky (“en dó”, “dos salmos”, “de ventos”). Non hai ningunha que estea numerada ao xeito tradicional. No mínimo, parece que estas obras mostran unha sintonía coas tradicións musicais que estes compositores herdaron, doa mesma forma que Schoenberg quixo situar as súas obras, aparentemente radicais e modernistas, nesa tradición, em concreto como herdeiro da obra de Brahms.

Webern: Konzert Op. 24 (1934)

O Konzert (Concerto) de Webernsuscita as mesmas dúbidas técnicas e musicais que a Symphonie. Ten tamén unha serie moi “ben organizada” (Exemplo 4), e un título igualmente suxerente, que en principio alude unha tradición musical moi ampla.

A serie

Example 4. The row of Webern’s Konzert (Op. 24) along with the trichordal and hexachordal divisions.

Once again, we have two equal hexachords of set class (014589) and a meaningful division into four trichords. This time, those trichords are all instances of the same set class: (014). This structural division is made abundantly clear in the first few measures, in which the row is set out in its four parts in separate instruments, pulse values, and registers. This is followed by a rest in all instruments. You couldn’t hope to a see a clearer row “exposition.”

But that’s not all. If you permute the order of those trichord cells, you can get other, related row forms:

- Obviously, reversing the order of the cells can give you a P/R pair of rows (P = 1234; R = 4321).

- Additionally in this case, the order 2143 gives you an I row, and so the reverse of that (3412) is an RI row.

That being the case, we have a set of four equivalent rows, and thus only twelve distinct row forms this time. For instance, P0 is the same as RI7 starting that rotation from the seventh note, as shown by the bold in the matrix below. This all amounts to a particularly clear and determined level of coherence.

Example 5 gives the row matrix. Again (and perhaps more surprisingly this time) this arrangement does not correspond to the allocation of P0 by Webern in the sketches.

| I0 | I11 | I3 | I4 | I8 | I7 | I9 | I5 | I6 | I1 | I2 | I10 | ||

| P0 | 11 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 9 | R0 |

| P1 | 0 | 11 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 10 | R1 |

| P9 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 10 | 6 | R9 |

| P8 | 7 | 6 | 10 | 11 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 9 | 5 | R8 |

| P4 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 0 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 1 | R4 |

| P5 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 2 | R5 |

| P3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 0 | R3 |

| P7 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 11 | 0 | 7 | 8 | 4 | R7 |

| P6 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 11 | 6 | 7 | 3 | R6 |

| P11 | 10 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 8 | R11 |

| P10 | 9 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 10 | 11 | 7 | R10 |

| P2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 11 | R2 |

| RI0 | RI11 | RI3 | RI4 | RI8 | RI7 | RI9 | RI5 | RI6 | RI1 | RI2 | RI10 |

Example 5. Row matrix for Op. 24.

Célula

Each cell can also be understood as an ordered trichord, like a miniature three-note row. Each iteration of the cell involves interval class 4 and interval class 1 in opposite directions. Across the four iterations in a row, we get each of the four ways of setting this out. In the case of P0, this involves <−1, +4>, <+4, −1>, <−4, +1>, and <+1, −4>.

That being the case (and at the risk of confusing matters), we could think of the P, R, I, and RI versions not just of each row, but of each cell. Continuing to work on the basis of P0, we have:

- P: <−1, +4>

- RI: <+4, −1>

- R: <−4, +1>

- I: <+1, −4>

In this way, each cell is related to every other as shown in Example 6:

| Tricordo 1 | Tricordo 2 | Tricordo 3 | Tricordo 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tricordo 1 | - | RI | R | I |

| Tricordo 2 | RI | - | I | R |

| Tricordo 3 | R | I | - | RI |

| Tricordo 4 | I | R | RI | - |

Example 6. Relationships between ordered trichords in the row for Op. 24.

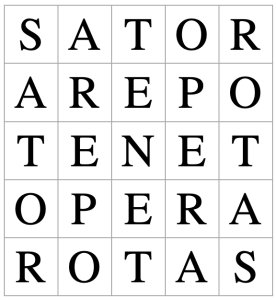

It’s hardly surprising given all of this that Webern was a fan of the “Sator Square”: a two-dimensional Latin palindrome that can be read in any direction and still make sense (Example 7).

That all said, the four-trichord approach is not the only way of using the row. It’s focal in the first movement, while the second movement primarily employs cells of two and four notes, highlighting interval class 1 (usually set out as a major seventh).

Debate

Once again, we have the looming question of a tradition with highly codified expectations. What kind of concerto might this be? The idea of a piano concerto finds some support in the distribution of row forms across the work. For instance, that first exposition of the row falls to instruments other than the piano, and then there’s the full-ensemble rest and a second exposition of the row on the piano alone. Conceptually at least, this is a neat fit for the double exposition of concerto first movements—one of the main hallmarks by which sonata form in concertos differs from other contexts.

Are we clutching at straws on the basis of just two statements of the row? Maybe, but then again, Webern is no stranger to the practice of cultivating comparable processes on the very small and large scale, so it’s worth paying attention to these kinds of clues as possible “statements of intention” in the same way that we should take notice of the first highly chromatic event in a Schubert sonata.

In this work, the relationship between piano and orchestra continues to reward analytical attention. After those first few measures, the first major section of the movement moves from that initial clear, successive separation of piano from ensemble to a situation where they remain separate in terms of row forms, but sound simultaneously. You can analyze the whole work in terms of this relation, and there are many moments where there appears to be both a structural boundary and a change in the relation between piano and ensemble. Examples include the separation in m. 50 and rejoining in m. 63.

Even if you find this line of reasoning compelling, you still face choices at every turn. For instance, you may see the piano’s ubiquity in the slower, quieter second movement (highly reminiscent of the traditional second movement) as a lyrical, dominant, soloistic part, or the opposite – in an accompanimental role. Alternatively, if you reject all of this in favor of an equality among the instruments (matching the equality among the tones, perhaps), then you may find more palatable the idea of reading this as a Concerto for Orchestra?

As with all music, there’s more than one way to look at this piece, and as with all analysis, we’re much more concerned with a view (“a way” of understanding the work) than trying to find comprehensive solution (“the way”). In short, the analysis of twelve-tone music is just like other forms of analysis: understanding the technical elements is necessary but not sufficient, and there’s always plenty of room for creative vitality.

- Bailey, Kathryn. 1991. Twelve-Note Music of Anton Webern: Old Forms in a New Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cook, Nicholas. 1987. A Guide to Musical Analysis. London: Dent.

- Harvey, Jonathan. 1982. “Reflection after Composition.” Tempo, no. 140, 2–4.

- Taruskin, Richard. 2010. “In Search of Utopia.” In Music in the Early Twentieth Century, chapter 12. New York: Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordwesternmusic.com/view/Volume4/actrade-9780195384840-div1-012010.xml

- Whittall, Arnold. 1977. Music since the First World War. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Try your own analysis of another work from this time, such as Webern’s Variations for piano, Op. 27, using a similar combination of technical row analysis with contextual discussion.

Media Attributions

- Sator square

- Note that this is sometimes set out in an alternative format, with P and I the other way around. Bailey (1991, appendix II) after Webern’s sketches uses this alternative format. These kinds of decisions are often not clearly "better" one way or the other. ↵

A particular version of a row in serial music; that is, prime, transposed, inverted, or retrograded.

A six-note collection. In serial music, "hexachord" is typically used to refer to either the first or last six notes of a twelve-tone row.

A group of pitch classes.

A collection of three notes.

The first large section in a sonata-form work. It usually establishes the main themes of a work and sets up a conflict that is later resolved in the work. This conflict often takes the form of differing key centers (such as when the primary theme of a sonata is in tonic and the secondary theme is in the dominant).

A section of a sonata form that is unstable, and that may or may not explore thematic material established in the exposition.

A section of a sonata-form work that brings back themes from the exposition and resolves the conflict established in the exposition.

A complex large-scale musical form that can be understood as an elaborate version of rounded binary form with a balanced component. The larger level names are as follows: Exposition (≈A), Development (≈B), and Recapitulation (≈A′). In general terms, the exposition contains two main sections (primary and secondary) separated by a transition. The secondary theme is presented in a non-tonic key in the exposition, and crucially, it is restated in the recapitulation in the tonic key. The exposition and recapitulation often end with a large suffix (closing section).

A type of form that has two core sections. These sections are often called "reprises" because each is typically repeated. There are two main types of binary form: rounded and simple.

A property of a row in which combining one hexachord from a version of a row with a hexachord from another version of a row creates the chromatic collection.

Contrapuntal writing without any specific thematic content.

The complete chromatic collection (i.e., all twelve pitch classes).

A group of pitch-class sets related by transposition or inversion. Set classes are named by their prime forms; for example, (012) is a set class.

Unordered pitch-class intervals; that is, the smallest possible distance in semitones between two pitch classes. Thus, mi2 and ma7 are both IC 1; ma2, mi7, +6 are IC 2; mi3, ma6, +2 are IC 3, etc. The largest interval class is six semitones, because if order is disregarded, the tritone is the largest possible interval.

The first part of a fugue, in which each voice states the subject or answer.