X. Orchestration

Core Principles of Orchestration

Mark Gotham

Key Takeaways

- “simultaneously” (or “vertically” if you prefer) for voicing chords, doubling melody lines, and handling texture;

- “successively” (or “horizontally”) for effects like orchestral crescendos.

Simultaneous (Vertical) Combinations

To b(lend) or not to b(lend) … that is the question … for “simultaneous” orchestration. For most tonal orchestrators, the default answer is a very clear “yes, blend!”

Voicing chords

As a rule of thumb for tutti orchestration, blend by treating each section as if it were self-contained. This applies to the large sections (winds, brass, strings), and often also to the smaller sub-sections (e.g., flutes) in the case of larger orchestras where there are greater numbers of each. For each section, follow the principles you learned in four-part writing. That’s right, the principles you’ve already learned about chordal writing still apply. Specifically, you’ll need to consider:

- The inclusion of all (or at least the most important) harmonic pitches.

- The number and prominence of each pitch, including avoiding the overdoubling of the third in a triad.

- The gaps between voices:

- We now see the densest packing in the middle.

- Continue to use larger gaps in the bass register (e.g., the octaves given by cello and double bass notated on the same pitch but sounding an octave apart).

- Continue to use smaller gaps higher up in the treble clef range.

- We tend to see more activity in the very highest registers in orchestral scores than in most other contexts; it’s usually best to return to wider spacing in those highest registers.

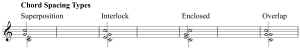

We have terminology for the different types of chord spacing as summarized in Example 1:

Example 1. Chord spacing types.

Context determines the best choice among these. For a blended sound, we often use integrated “interlocking” voicing, taking care to balance the different strengths of each instrument according to the register; conversely, to achieve a different color for each note, use wider spacing. [1]

Doubling lines

The approach to blending in doubling lines again involves finding a compatible balance of (equally strong) instruments and registers. The second part (m.1 4ff.) of Mozart 40/iii is effectively a two-part invention and an intriguing example of blended, balanced lines. Both of the two parts are played in each of the three octaves, and by both winds and strings.

As always, this default is not a law like that of gravity in physics; composers will diverge from this blended practice for creative and compositional effect in just the same way that they do with any other parameter. Perhaps the most famous example of an odd doubling is provided by Schubert 8/i. The first theme (m. 13) sees the extraordinary doubling of a single oboe and clarinet in unison. While some commentators have seen this as an error, it’s probably deliberate on Schubert’s part as a way of creating an unsettled feel that entirely befits the mood of the music. It also contrasts with a second theme (reh. A, m. 42): a cello theme accompanied by the optimally blended viola and clarinet in thirds.

Texture

The choice of instruments, register, and more can help support and define the wider texture. For instance:

- Polyphonic writing: Tends to see instruments and groups balanced and blended. Examples include fugues and the Mozart invention just discussed.

- Melody and accompaniment: Foregrounds the melodic instrument by placing it in its best range, often at the top of the texture (as in other contexts), and with other accompanimental parts contrasting in:

- Timbre, accompanying a solo woodwind line by full strings, for instance.

- Register (as discussed).

- Texture, with less or a different kind of rhythmic activity. This is similar to the kind of complementary rhythmic patterns you often find in polyphonic music: in both cases, we’re trying to have more than one element at once, but keep them noticeably distinct.

Successive (Horizontal) Combinations

We’ll look here at forms of succession on two timescales: at the level of individual notes (small scale) and of whole sections (large scale).

Firstly, once again, everything you’ve learned about voice-leading still applies. (Yes, this will be a recurring mantra.) Most of the time, it will be eminently possible to reduce apparently complex orchestral scores down to a two-, three-, or four-part texture with clear and consistent doublings and with “correct” voice-leading.

In handling successive sections, antiphony is a highly favored method for distributing material, creating timbral variety, and articulating the form. This can take the form of whole blocks of material being passed from strings to winds (common in early orchestral scores of the Baroque era), or of more subtle effects. For instance, look at the first page of “In the Hall of the Mountain King” from Grieg’s Peer Gynt suite:

At the repeat of the tune, the only variation is antiphony (strings-to-winds). The material (both tune and accompaniment) and register are identical. Later, this strings-to-winds principle continues to the upper voices as the register expands upward. Let’s take a closer look at that crescendo.

Crescendos

We have a range of tools at our disposal for achieving an effective orchestral crescendo. Apart from mere dynamic markings, we can:

- Add instruments, often moving from the “lightest” to “heaviest” instruments: broadly, strings-wind-brass-percussion (e.g., Grieg rehearsal mark A).

- Expand the overall range, often upward from the bass or outward from the center (e.g., Grieg rehearsal marks A and B).

- Diversify the note values used, adding sustained, longer notes and/or tremolo, shorter ones, perhaps through note repetitions (e.g., Grieg rehearsal mark B).

Take a look at rehearsal mark B in the Grieg, and notice the:

- Forces and register: We now have the full orchestral and full register in use except for one instrument, the piccolo, which is reserved for the top C♯, four measures later. The piccolo is removed at rehearsal mark C and reintroduced at rehearsal mark D for a similar effect. Likewise, the final page briefly removes the bass for the piano passage before the final fff chord.

- Wider range of note values: The accompanimental figure (16th-16th-8th on the weak beats), first introduced by the viola part at rehearsal mark A, has now become focal, adding rhythmic density to the score. This is further enhanced by the upper strings playing the theme with repeated (sixteenth) notes and the timpani roll. Conversely, the horns introduce longer (half) notes, lending a more sustained sound to the previously staccato accompaniment.

As an aside, it’s worth noting that moving from lightest to heaviest instruments (strings-winds-brass-percussion) is related to overall playing time: the strings generally play the most, the percussion the least. This is partly for pragmatic reasons: brass players would keel over from exhaustion if you had them play the string parts—there’s just too much playing time and not enough resting time in between. You’ll find that the best choices for pragmatic reasons and musical ones often go together in this way.

Holding a timbre back for effect

Percussion parts are the clearest indication of the practice of holding a timbre back for effect. One of the essential skills of the percussionist is being able to count hundreds of measures of rest and then come in with a bang at the crucial, climatic moment. Here’s an extract from the triangle part for Mahler 4/iii. At reh. 12, a crash cymbal marks the moment of arrival, and the triangle leads a glorious texture, full of all the rich effects described above (register, texture, sustain, and note density). The triangle is one of those instruments that can be pretty well guaranteed to cut through most any texture and make an impact. The glockenspiel and piccolo are also good in this role.

This holding back of a timbre is very often for loud and/or climactic moments, but not always. For instance, reserving an entirely new sound until near the end of a work can be extremely effective. Perhaps the most iconic example is to be found in Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, where the antique cymbal is not used until near the end. (This is a “new” sonority for the piece, and even for Western audiences of the time.) The crucial moment comes at reh. 10, (8’56” in the following recording), but clearly the effect depends on listening to the wider context.

Dovetailing parts

Finally, in an approach somewhat complementary to antiphony, orchestrators will often “dovetail” parts: share a continuous line out between different voices. This can be:

- related to antiphony (the melodic line moves from part to part)

- or the opposite: ensuring continuity/cohesion within a line on instruments for which that would be impractical

- tailored in subtle ways to demarcate a rhythm

Take a look at Smetana’s Vltava to this effect:

- At the opening, the flutes dovetail by overlapping by one note on the downbeat. This is easy to play, and it allows them to share the long line. It could be more seamless, though, by slurring onto the downbeat, rather than separating that note with a staccato. The resultant effect is of a fluid line, but with the beats clearly demarcated.

- When the clarinets enter, we have dovetailing both within and between those subsections: the flute continues as before, the clarinets follow suit, and this leads to further pairs of Fl.1 + Cl.2 and Cl.1, Fl.2.

- The strings take a different approach at their entrance at m. 36. The line continues to be shared out among the string parts, but the groupings break it up into clear 6+3+3 (2+1+1) rhythms. This follows a period of syncopated accents in the winds.

This gives some sense of how much variety can be achieved within the simple dovetail pattern. It can get even more detailed, as in the following passage from Rachmaninoff 3/ii (reh. 42). This rhythm saturates the four options in the space. It is somewhat dovetailed: it is not dovetailed within either the wind or string sections, but is dovetailed between them. The texture makes great use of the resources at hand, sparkles with detail, and gives the players interesting parts to think about (an important and easily overlooked consideration).

- Dovetailing: transcribe the sixteenth-notes part (piano right hand) of Louise Reichardt’s Unruhiger Schlaf (12 Gesänge, no. 6) for two clarinets, dovetailing regularly every quarter or half note. A score is available here.

- For a recent article on this topic (even more recent than this chapter!), see McAdams, Stephen, Meghan Goodchild, and Kit Soden. 2022. ‘A Taxonomy of Orchestral Grouping Effects Derived from Principles of Auditory Perception’. Music Theory Online 28 (3). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.22.28.3/mto.22.28.3.mcadams.html.

Media Attributions

- C3 Chord Spacing Types

- For more textbook examples, see Adler (2002, 253); Piston (1955, 396). ↵

A call-and-response texture in which musical material is passed from group to group.