169

Overview & History

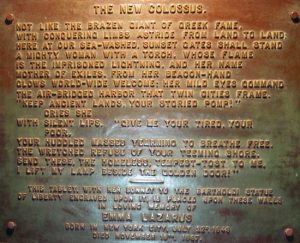

Few poems have slipped into American culture as fundamentally as Emma Lazarus’ “The New Colossus”. Written in 1883, this poem was created for an auction to raise money for the construction of the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal, a famous statue gifted to the United States from France to honor America’s Centennial. Being Jewish and having helped Jewish immigrants who fled from pogroms in Russia, Lazarus knew the affects of xenophobia and the importance of the United States being a symbol of Freedom and refuge. You can see this message throughout “The New Colossus”, portraying the ideal that the United States take in all sorts of persecuted peoples, and that this land holds a “golden door” to safety. This message is particularly impactful when you take into account the time-frame of these events. A year prior to Lazarus writing this poem the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act had been passed and signed by President Chester A. Arthur. This act, meant to appease middle and lower-class Americans who felt as if Chinese laborers were taking jobs away from them, greatly restricted future immigration from China. Additionally, the act impacted Chinese immigrants already inside the country making it so if they left they had to obtain a certificate of reentry prior to leaving, a complicated and difficult task, as well as prohibiting Federal and State courts from granting Chinese immigrants citizenship. Lazarus’ “The New Colossus” became enshrined on a plaque on the Statue of Liberty in 1903, a year after Congress made the Exclusion Act permanent and strengthened it requiring all Chinese immigrants to have a certificate of residence or face deportation.

Textual Summary & Analysis

The poem starts out with a deified description of the Statue of Liberty, glorifying its elegance above that of the famous Greek statue the Colossus of Rhodes, one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Lazarus draws the distinction between how the Colossus of Rhodes symbolized conquest with “limbs astride from land to land”. Meanwhile, her New Colossus, the Statue of Liberty, is portrayed as a symbol of refuge for the persecuted, referring to America’s shores as “sunset gates” and dubbing the Statue of Liberty as the “Mother of Exiles”. While benevolent and kind, this symbol of America is also portrayed as strong and mighty, characterizing Lady Liberty as “A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame, Is the imprisoned lightning.” This worked as an appeal to the patriotism of Americans, allowing for Lazarus to make her more political statement in the following lines. In the final five lines of her most famous work, Lazarus issued a call for the United States to be the idealistic symbol of freedom people now commonly claim it to be. Having Lady Liberty utter the now famous lines, “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free”.

Legacy

Lazarus’ “The New Colossus” was memorialized on the Statue of Liberty in 1903 and has since entered into United States’ consciousness as a defining piece of literature for American identity. Its lines and inspirational message has since become a sort of rallying cry for refugee and immigration activist movements throughout American history, being a common symbol used to criticize legislation and political actions meant to negatively impact immigrants and refugees. Recently her words have been used to criticize actions taken by President Donald Trump such as his alleged persecution of Hispanic immigrants and his controversial travel ban. Regardless of political beliefs, Lazarus’ poem undoubtedly helped cement the concept of the United States as a symbol of freedom for the world into the American narrative.

“The New Colossus Text”

Sources:

Lazarus, Emma. “The New Colossus.” 1883. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46550/the-new-colossus.

“Emma Lazarus.” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Emma-Lazarus.

United States. Cong. Chinese Exclusion Act. 47th Cong. 1st sess. The Library of Congress. Web. https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/47th-congress/session-1/c47s1ch126.pdf.

“The Chinese Bill Passed.” New York Times, 10 March 1882. p. 1. https://www.nytimes.com/1882/03/10/ archives/the-chinese-bill-passed-a-vote-of-nearly-two-to-one-in-the.html

Media Attributions

- Good Statue of Liberty

- Plaque