2

Chapter 2 Outline:

2.1 Legal Roots of Consumer Protection

2.2 Federal Entities

2.3 State Entities

Introduction

The government has a strong interest in ensuring that products consumers purchase are safe for their intended use. Imagine taking a product off the shelf, unsure whether or not the product contains sharp debris or toxic chemicals, or asking yourself whether or not the product will explode at any moment.

2.1 Legal Roots of Consumer Protection

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand the need for legally enforceable standards for products

- Describe the unfortunate tragedy that led to significant changes in federal legislation with respect to cosmetic and drug safety

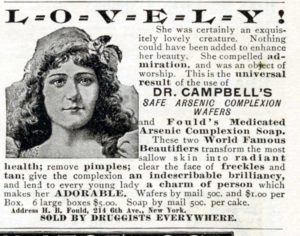

Before the development of consumer product safety standards based on scientific advances, numerous beauty products, for example, contained poisonous chemicals, including lead, arsenic, mercury, and even the radioactive element radium. Wallpaper, beer, wrapping paper, candles, ornaments, and even sweets all contained arsenic. These products were at their height of popularity in the late 1880s to the early 1900s, though these ads were still found in the U.S. as late as the 1920s, and finally banned from cosmetic use in 1938 with the passage of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act (See Figure).

This legislation, first introduced in 1933, took 5 years to make it through Congress. Like many pieces of languishing legislation, a disaster finally spurred Congress to take action. In 1937, a reputable Tennessee drug company, S.E. Massengill, advertised a new wonder drug, Elixir Sulfanilamide, that doctors used to treat strep throat and other ailments. Sulfanilamide had been used safely in powder and pill form, until the company’s chief chemist, Harold Cole Watkins discovered that sulfanilmaide would dissolve in dyethelyne glycol, creating a mixture satisfactory in appearance, smell, and flavor. Without testing for toxicity, in early September 1937 the company sent 633 shipments of the new compound all over the country.

Without any kind of required safety or pharmaceutical testing, Watkins failed to notice that dyethelyne glycol, a chemical used as an antifreeze, is a deadly poison. Thus, S.E. Massengill sent out a toxic “remedy” marketed to contain alcohol, which it did not contain, for use to treat sore throats in children. By mid October, an FDA inspector reported that 8 children and 1 adult had died from Elixir Sulfanilamide. Warning messages and inspectors were dispatched to stop the use and collect the poison that had been distributed. Often requiring detective work to track the salesmen and the products down, federal, state, and local officials were able to recover 234 gallons and 1 pint of the 240 gallons distributed. In all, more than 100 children and adults died in 15 states.

The FDA charged S.E. Massengill with “misbranding,” due to “Elixr” implying that the product contained alcohol, when in fact it did not. If the product had been called a “solution” rather than “Elixr”, no charge could have been brought under the FDA. In a call to strengthen the inadequate regulation of drugs, then FDA commissioner Walter Campbell said:

It is unfortunate that under the terms of our present inadequate Federal law, the Food and Drug Administration is obliged to proceed against this product on a technical and trivial charge of misbranding. …[The Elixir Sulfanilamide incident] emphasizes how essential it is to public welfare that the distribution of highly potent drugs should be controlled by an adequate Federal Food and Drug law. … We should not lose sight of the fact that we had many deaths and cases of blindness resulting from the use of another new drug, dinitrophenol, which was recklessly placed upon the market some years ago. Deaths and blindness from this [drug] are continuing today. We also should remember the deaths resulting from damage to the liver that have occurred from cinchophen poisoning, a drug often recommended in such painful conditions as rheumatism. We also have unfortunate poisoning, acute and chronic, resulting from thyroid and radium preparations improperly administered to the public. These unfortunate occurrences may be expected to continue because new and relatively untried drug preparations are being manufactured almost daily at the whim of the individual manufacturer, and the damage to public health cannot accurately be estimated. The only remedy for such a situation is the enactment by Congress of an adequate and comprehensive national Food and Drugs Act which will require that all medicines placed upon the market shall be safe to use under the directions for use.

This tragic series of failures did hasten the passage of improved legislation, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 (FFDC), which is the current regulatory framework. Since its introduction, Congress has amended the FFDC dozens of times, creating, according to the FDA, “one of the world’s most comprehensive and effective networks of public health and consumer protections.”

Laws designed to protect the public from harms are rarely passed proactively. Much like the tragedy described above, other legal protections have come about after tragedies. The following table highlights important developments in consumer protection:

| 1890 | Sherman Antitrust Act |

| 1891 | First local Consumers’ League formed, New York City |

| 1898 | National Consumers’ League created |

| 1906 | Upton Sinclair’s book, The Jungle, exposes meat packing industry and prompts passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act |

| 1906 | Pure Food and Drug Act (The Wiley Act) |

| 1914 | Federal Trade Commission Act, to regulate unfair methods of competition in commerce |

| 1927 | Your Money’s Worth, written by Chase and Schlink attacks the advertising industry, calls for product testing and proposes “Consumers Club” |

| 1929 | Consumers’ Research, Inc. formed to test products |

| 1930s | Food and Drug Administration (FDA) dramatizes the need for new legislation with product exhibit called “Chamber of Horrors,” which includes items like an eyelash dye which causes blindness |

| 1937 | Liquid form of a new sulfa drug kills 100 people, prompting an FDA bill requiring manufacturers to prove the safety of new drugs before marketing |

| 1938 | Wheeler-Lea amendment gives FTC Act the power to protect consumers from unfair or deceptive acts or practices |

| 1946 | Ex-Madison Avenue copywriter Frederick Wakeman writes The Huckster, an exposé on the advertising industry, creating public outcry |

| 1950 | Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver’s investigation into drug industry reveals weakness in safety testing and calls for amendments to strengthen powers of FDA |

| 1957 | Hidden Persuaders, written by by Vance Packard exposes advertising industry |

| 1962 | President John F. Kennedy outlines Consumer Bill of Rights |

| 1962 | Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring exposes the dangers of pesticides and chemicals |

| 1964 | President Lyndon Johnson creates Office of Special Assistant to the President for Consumer Affairs |

| 1965 | Ralph Nader’s book, Unsafe at Any Speed, presents evidence of hazards in automobiles |

| 1966 | Highway Safety Act passed |

| 1966 | Truth-in-Packaging Bill |

| 1977 | Fair Debt Collection Practices Act |

| 1980 | Federal Trade Commission Improvement Act |

| 1991 | Truth in Savings Act |

| 1999 | Gramm-Leach Bliley Act Regulation, Privacy of Consumer Financial Information |

| 2011 | Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act creates the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau |

| Source: Connecticut State Department of Consumer Protection, https://portal.ct.gov/DCP/Agency-Administration/About-Us/History/The-1900s |

2.2 Federal Entities

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the missions of the federal agencies that create rules and systems that protect consumers

The federal government (i.e. the executive branch agencies) has an interest (and the authority from the Constitution through Congress) to create rules and systems that are designed to protect consumers. This section will cover a number of the federal agencies that serve to protect the interests of consumers.

- Federal Trade Commission (FTC)-established in 1914 as an anti-trust effort (to be discussed in detail in Chapter 4), the FTC’s mission is to protect “consumers and competition by preventing anticompetitive, deceptive, and unfair business practices through law enforcement, advocacy, and education without unduly burdening legitimate business activity.” The FTC benefits consumers in numerous ways. According to the FTC, it is the only federal agency with both consumer protection and competition jurisdiction in broad sectors of the economy. The FTC pursues vigorous and effective law enforcement; advances consumers’ interests by sharing its expertise with federal and state legislatures and U.S. and international government agencies; develops policy and research tools through hearings, workshops, and conferences; and creates practical and plain-language educational programs for consumers and businesses in a global marketplace with constantly changing technologies. FTC’s work is performed by the Bureaus of Consumer Protection, Competition and Economics. Source: https://www.ftc.gov/about-ftc/what-we-do

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-established in 1906, the Food and Drug Administration is responsible for protecting the public health by ensuring the safety, efficacy, and security of human and veterinary drugs, biological products, and medical devices; and by ensuring the safety of our nation’s food supply, cosmetics, and products that emit radiation. FDA also has responsibility for regulating the manufacturing, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products to protect the public health and to reduce tobacco use by minors. FDA is responsible for advancing the public health by helping to speed innovations that make medical products more effective, safer, and more affordable and by helping the public get the accurate, science-based information they need to use medical products and foods to maintain and improve their health. Source: https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/what-we-do

- Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC)-established in 1972, CPSC is charged with protecting the public from unreasonable risks of injury or death associated with the use of the thousands of types of consumer products under the agency’s jurisdiction. Deaths, injuries, and property damage from consumer product incidents cost the nation more than $1 trillion annually. CPSC is committed to protecting consumers and families from products that pose a fire, electrical, chemical, or mechanical hazard. CPSC’s work to ensure the safety of consumer products – such as toys, cribs, power tools, cigarette lighters, and household chemicals – contributed to a decline in the rate of deaths and injuries associated with consumer products over the past 40 years. Source: https://www.cpsc.gov/About-CPSC.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB)-established in 2011 in the wake of the housing crisis of 2009, the CFPB was created to provide a single point of accountability for enforcing federal consumer financial laws and protecting consumers in the financial marketplace. Before, that responsibility was divided among several agencies. Their work includes: rooting out unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts or practices by writing rules, supervising companies, and enforcing the law, enforcing laws that outlaw discrimination in consumer finance, taking consumer complaints, enhancing financial education, researching the consumer experience of using financial products, and monitoring financial markets for new risks to consumers. Source: https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/the-bureau/

- National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA)-established in 1970, the NHTSA is responsible for keeping people safe on America’s roadways. Through enforcing vehicle performance standards and partnerships with state and local governments, NHTSA reduces deaths, injuries and economic losses from motor vehicle crashes. Source: https://www.nhtsa.gov.

2.3 State Entities

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand that states have different consumer protection statutes

- Describe how the state of Illinois enforces consumer protection statutes

Each state has their own consumer protection oriented agencies/officers that serve to enforce their respective state consumer protection laws. These state laws are commonly referred to as unfair and deceptive acts and practices (UDAP) laws. The effectiveness of these laws varies greatly from state to state.

According to the National Consumer Law Center:

In many states, the deficiencies are glaring. Legislation or court decisions in dozens of states have narrowed the scope of UDAP laws or granted sweeping exemptions to entire industries. Other states have placed substantial legal obstacles in the path of officials charged with UDAP enforcement, or imposed ceilings as low as $1,000 on civil penalties. And several states have stacked the financial deck against consumers who go to court to enforce the law themselves.

Specifically to Illinois, the Consumer Protection Division of the state attorney general protects consumers and businesses victimized by fraud, deception, and unfair business practices. The work of the Division is carried out by the following bureaus: Consumer Fraud Bureau, Charitable Trust Bureau, Franchise Bureau, Health Care Bureau, and Military and Veterans Rights Bureau.

Endnotes

Carol Ballentine. Sulfanilamide Disaster, FDA Consumer magazine (1981), https://www.fda.gov/files/about%20fda/published/The-Sulfanilamide-Disaster.pdf.

Consumer Protection in the States, National Consumer Law Center (2018), https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/udap/udap-report.pdf.

Natalie Zarrelli. The Poisonous Beauty Advice Columns of Victorian England, Atlas Obscura (2015), https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-poisonous-beauty-advice-columns-of-victorian-england.