3

Chapter 3 Outline:

3.1 Consumer Product Safety Commission

3.2 Product Safety Standards

3.3 Product Recalls

3.4 Product Liability

3.5 Consumer Arbitration

Introduction

The principle of caveat emptor, “let the buyer beware,” dates back to the period in which Roman Law served as the legal system of ancient Rome from the 8th century to the 7th century A.D. The tradition and use of Roman law lasted well into the 18th century, carrying with it the principle of caveat emptor. During the Middle Ages, however, caveat emptor was not a principle found among the church and feudal authorities.

Churchmen established the order of obedience and imposed religious purposes upon all human activities, to include wealth and trade. The teaching of the gospel directed Christians to sell what he had and give to the poor, while above all, avoid the pursuit of monetary gain. Thus, in the early Middle Ages, trade was deemed worldly, not heavenly. Influential theologian and philosopher, Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225 – 1274) composed questions and formulated answers to those questions about the ethics of sales and faulty items, showing that selling faulty items or misleading in sales in conflict with passages in the Bible.

Summa Theologica, II, q. 77, a. 2 (in part)

Question 77, cheating which is committed in buying and selling

Article 2. Whether a sale is rendered unlawful through a fault in the thing sold?

I answer that, A threefold fault may be found pertaining to the thing which is sold. One, in respect of the thing’s substance: and if the seller be aware of a fault in the thing he is selling, he is guilty of a fraudulent sale, so that the sale is rendered unlawful. Hence we find it written against certain people (Isaiah 1:22), “Thy silver is turned into dross, thy wine is mingled with water”: because that which is mixed is defective in its substance.

Another defect is in respect of quantity which is known by being measured: wherefore if anyone knowingly make use of a faulty measure in selling, he is guilty of fraud, and the sale is illicit. Hence it is written (Deuteronomy 25:13-14): “Thou shalt not have divers weights in thy bag, a greater and a less: neither shall there be in thy house a greater bushel and a less,” and further on (Deuteronomy 25:16): “For the Lord . . . abhorreth him that doth these things, and He hateth all injustice.”

A third defect is on the part of the quality, for instance, if a man sell an unhealthy animal as being a healthy one: and if anyone do this knowingly he is guilty of a fraudulent sale, and the sale, in consequence, is illicit.

In all these cases not only is the man guilty of a fraudulent sale, but he is also bound to restitution. But if any of the foregoing defects be in the thing sold, and he knows nothing about this, the seller does not sin, because he does that which is unjust materially, nor is his deed unjust, as shown above (II-II:59:2). Nevertheless he is bound to compensate the buyer, when the defect comes to his knowledge. Moreover what has been said of the seller applies equally to the buyer. For sometimes it happens that the seller thinks his goods to be specifically of lower value, as when a man sells gold instead of copper, and then if the buyer be aware of this, he buys it unjustly and is bound to restitution: and the same applies to a defect in quantity as to a defect in quality.

In so-called modern times, the law has swung from no legal requirement to provide relief (i.e. caveat emptor) to near absolute liability, meaning that sellers, merchants under the uniform commercial code, manufacturers, and distributors can be held liable for injuries caused by products they sell, produce, or distribute.

Federal and state agencies have an interest in ensuring products sold to consumers meet safety standards. The Consumer Product Safety Commission is one such federal agency responsible for investigating, testing, and communication issues related to unsafe products.

3.1 Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC)

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand the role of the CPSC

- Illustrate the dangers of counterfeit products

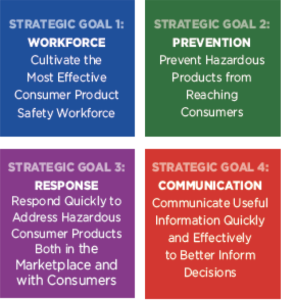

As described in Chapter 2, early product safety legislation dealt primarily with food, drug and cosmetic products. President Richard Nixon signed the Consumer Product Safety Act (CPSA) into law in 1972, creating the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). The CPSC’s mission is “keeping consumers safe” and their vision is “a nation free from unreasonable risks of injury and death from consumer products.” To achieve their mission and realise the vision, the agency has four strategic goals. (See Figure).

The CPSC is empowered through their enabling statute, to meet their objectives through consumer monitoring, research, investigations, safety standard-setting, and enforcement powers. The CPSC’s jurisdiction is primarily governed by the definition of “consumer product.” Though broad in scope, this definition contains a number of products regulated by other agencies that are carved out of the definition.

CPSC does not have jurisdiction over the safety standards for the following: 1) automobiles and motorcycles (Department of Transportation), 2) drugs and cosmetics (Food and Drug Administration), and 3) alcohol, tobacco, and firearms (Department of Treasury-Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau). Still, the CPSC has jurisdiction over 15,000 product types.

Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act

In 2008, Congress passed the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act (CPSIA) that restricts the levels of hazardous materials in products either imported or made in the U.S, especially products made for children. The CPSIA included provisions addressing, among other things, lead, phthalates, toy safety, durable infant or toddler products, third-party testing and certification, tracking labels, imports, ATVs, civil and criminal penalties, and SaferProducts.gov, a publically-searchable database of reports of harm. The CPSIA also repealed a challenging agency funding limitation and increased the number of authorized CPSC commissioners from three to five.

The CPSIA defines the term “children’s product” and generally requires that children’s products:

- Comply with all applicable children’s product safety rules;

- Be tested for compliance by a CPSC-accepted accredited laboratory, unless subject to an exception;

- Have a written Children’s Product Certificate that provides evidence of the product’s compliance; and

- Have permanent tracking information affixed to the product and its packaging where practicable.

The CPSIA also requires domestic manufacturers or importers of non-children’s products to issue a General Certificate of Conformity (GCC). These GCC’s apply to products subject to a consumer product safety rule or any similar CPSC rule, ban, standard or regulation enforced by the Commission.

Counterfeit Products

While not a new phenomenon, counterfeit products have proliferated as a result of ecommerce. In years past, a consumer would need to go to bootleg stores to purchase knockoff items but since the advent of the internet, counterfeiters have found ways to access American consumers through Amazon as well as many other sites, and Chinese consumers through Alibaba.

Amazon did not always take steps to police the authenticity of the products sold by third party distributors. However, in 2020, Amazon revealed that it blocked 10 billion attempted counterfeit listings and destroyed 2 billion counterfeit items in its warehouses. Despite this high number, counterfeit products are still easily listed on Amazon. Counterfeit products flooding the market on Amazon and other retailers are estimated to be worth nearly $1 trillion. Many of these products are not knockoff designer handbags or shoes, but are everyday products like soap, baby formula, and reusable metal water bottles. Other counterfeit products may have tragic consequences for the consumer.

Counterfeit safety equipment like bicycle and motorcycle helmets, and automotive parts including airbags, can have devastating consequences for consumers and can be difficult to distinguish from the real thing. However, there are ways to help spot fake products. Be aware of the following:

-

- Prices that are too good to be true. An authentic Specialized Evade bicycle helmet retails for $275. A counterfeit model can be obtained for less than $21.

- An untrusted or dubious looking website. Online marketplaces, such as Amazon, Ebay, and AliExpress are havens for counterfeit products. Authentic items are obtained from the manufacturers websites or reputable dealers.

- Customer reviews and seller profiles. Certainly not all sellers are fraudulent. Reading customer reviews of not only the product, but also that mention the seller can be a good indicator of the legitimacy of the seller.

- Country. An estimated 72% of counterfeit goods bound for sale in the U.S., European, and Japanese markets are produced in China. Other countries that export counterfeit goods include Turkey, Thailand, Singapore, and Malaysia.

- Imagery/product features. Counterfeit products may look substantially similar to the authentic item, but to the discerning consumer, differences may be significant. Safety items, such as bicycle helmets, authorized to be sold in the U.S. will contain safety certification stickers, whereas counterfeit safety items may not contain the proper certification stickers or may contain incorrect labels. A counterfeit product may also be indicated by:

- Poor construction quality from poor quality materials

- Flimsy, poorly printed packaging

- Large fonts, misspelled words

- Loose stitching

- Abnormally large logos

- Includes other brands logos (Source: https://www.specialized.com/ca/en/counterfeit.

- Item descriptions. The description of the item is an area counterfeiters will often neglect. Carefully cross-referencing the item descriptions of the counterfeit with the authentic product can reveal inconsistencies. Source: https://www.incoproip.com/how-to-spot-counterfeit-goods/.

3.2 Product Safety Standards

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand the development and role of Underwriters Laboratories

- Describe when mandatory and voluntary standards apply

In May 1893, the World’s Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World’s Fair), opened as a celebration of the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ so-called discovery of the new world. The fair featured nearly 200 buildings spread over 600 acres along Chicago’s southern lakeshore. The buildings and exhibits were a mixture of grand classical architecture and modern (yet unsafe) technology. The achievement, known as the “White City,” which was lit by electricity at night received glowing reviews. Yet underneath the grand buildings were miles of criss-crossing electrical wires and untried electrical connections routed in close proximity to the flammable plaster and jute (a glossy plant fiber) facades. The danger juxtaposed to the horror of the Great Chicago fire of 1871 caused great hesitancy with the insurance underwriters and led the exposition director to beef up the fire department presence far more than he had initially planned for. The Chicago Underwriter’s Association decided to contract their counterpart in Boston who sent a promising young electrical engineer, William H. Merill, to review the wiring and exhibits to understand the risks the Palace of Electricity and White City posed. Despite a few tragic fires and serial killer H.H. Holmes (see Devil in the White City by Erik Larson), the fair was considered a success with 27 million visitors. After the close of the fair the buildings continued to pose a hazard. A massive fire broke out in 1894 destroying most of the White City.

In the aftermath of all that happened, electrical contractors began to ask William H. Merill how to confirm the safety of their technology. Seeing an opening, Merill founded the Underwriters’ Electrical Bureau in Chicago. The first laboratory began safety testing arc lamps, switches, sockets, and wires. After several years of work, ready for the national stage, Merill incorporated the Bureau as Underwriter Laboratories, Inc. (UL). A key component of UL’s early work was the development a label service that certified that the individual products met UL’s safety standards. Over the next hundred years, UL continued to develop services and standards that today mark credibility and offer value to insurance underwriting entities, which ultimately keep consumers safe.

Voluntary v. Mandatory Standards

Underwriter Laboratories and the ASTM International (formerly known as the American Society for Testing and Materials) are two private organizations that set voluntary standards for importers and manufacturers. Founded in 1898, ASTM International has over 12,000 standards that cover a wide range of industries and products. These standards are typically voluntary for manufacturers. However, some government regulations may require adherence to some standards written by UL, ASTM, ANSI, and other organizations.

Various federal laws, passed by Congress, set standards for the manufacturing, labeling, packaging, and distribution of a wide variety of products. The following federal laws, in addition to the CPSA and CPSIA (described above) set product standards:

- Poison Prevention Packaging Act of 1970 requires household substances to be packaged in child-resistant packaging.

- Federal Hazardous Substances Act of 1960 requires precautionary labeling on the immediate container of hazardous household products to help consumers safely store and use those products and to give them information about immediate first aid steps to take if an accident happens. The Act also allows the Consumer Product Safety Commission to ban certain products that are so dangerous or the nature of the hazard is such that the labeling the act requires is not adequate to protect consumers.

- Flammable Fabrics Act of 1953 allows the CPSC to issue mandatory standards for clothing textiles, vinyl plastic film, carpet and rugs, children’s sleepwear, mattresses, and mattress pads.

3.3 Product Recalls

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Describe the role of the CPSC in required and voluntary recalls

- Understand the ethical issues of the Takata airbag scandal

The government agencies responsible for ensuring products for consumer consumption are safe, have the authority to issue recalls when they receive complaints from consumers, or conduct their own investigations to determine if products under their jurisdiction violate the law and are therefore unfit for consumers. The CPSC, for example, can issue a recall for products they deem to be unsafe. The CPSC issues up to 400 recalls a year. The process for determining whether or not a product is safe often starts at ports where 8,000 shipments a year are examined by CPSC employees box by box. Products flagged at the port are sent to a laboratory in Maryland for further testing. The CPSC also looks at consumer complaints as well as issues that are required to be reported by companies. Around half of the reports from the CPSC result in a recall, with most being voluntary. Even when a recall is issued only around 65 percent of products are returned or repaired. Rather than solely relying on the government to issue a recall, filling out the product registration card for the product a consumer purchases may help that manufacturer notify the consumer when they have discovered an issue with that product.

Takata Airbags: Ticking Time Bombs

The Japanese auto parts manufacturer, Takata Corporation, began manufacturing airbags used in cars and trucks in 1988. In 2013, aware of 6 deaths and hundreds of injuries, Honda recalled 3.6 million cars with the defective airbags. Other manufacturers issued subsequent recalls after the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) received complaints of three deaths. Takata did not issue a recall until they were compelled to by the NHTSA in November 2014. By May 2015, Takata recalled 53 million vehicles. Most of the models of cars were from 2002 to 2015.

The Japanese auto parts manufacturer, Takata Corporation, began manufacturing airbags used in cars and trucks in 1988. In 2013, aware of 6 deaths and hundreds of injuries, Honda recalled 3.6 million cars with the defective airbags. Other manufacturers issued subsequent recalls after the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) received complaints of three deaths. Takata did not issue a recall until they were compelled to by the NHTSA in November 2014. By May 2015, Takata recalled 53 million vehicles. Most of the models of cars were from 2002 to 2015.

In 2016, the Department of Justice to file criminal charges against the Takata Corporation and three of its employees were charged with wire fraud and conspiracy. According to the indictment, in the late 1990’s Takata developed airbag inflators that relied upon an unstable, highly combustable propellant, ammonium nitrate. From 2000 to 2015, though company executives, employees, and agents knowingly devised and participated in a scheme to sell faulty, inferior, and non-conforming inflators to car manufacturers. In the U.S., there were 19 deaths and 400 injuries as a result of the faulty airbags. As a part of a plea agreement, Takata agreed to pay $1 billion in criminal penalties.

The Takata Recall Spotlight at NHTSA.gov provides a list of vehicles affected and the ability to check the Vehicle Identification Number (VIN) to see if it is affected by the recall.

https://www.nhtsa.gov/equipment/takata-recall-spotlight

Agencies with the authority to recall products include the FDA, CPSC, NHTSA, EPA, USDA, and the U.S. Coast Guard. Recalls.gov serves as a one-stop shop for consumers to obtain the latest recall information.

3.4 Product Liability

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the tort basis for product liability

- Explain the contract basis for product liability

- Discuss strict liability and how that differs from contract and tort basis

While the CPSC, FTC, and state consumer protection agencies work to protect consumers from products through passing and enforcing standards, conducting investigations and inspections, and imposing appropriate penalties on manufacturers and sellers, individual consumers have the ability to file lawsuits against manufacturers and sellers of defective products. The next three sections will discuss the legal bases (or theories) to obtain recovery when injured by a product. A plaintiff may rely on one or more of these theories upon which to base his or her product liability claim.

Tort Law Basis for Product Liability

Product liability is mainly derived from tort law, of which negligence forms the central part of product liability law. In order to prove a product liability claim under the theory of negligence, the plaintiff must prove 5 elements:

- Duty: the manufacturer of the product in question owed a duty of care to the plaintiff;

- Breach of duty: the manufacturer breached the duty of care owed to the plaintiff;

- Actual cause: the breach of duty was the actual cause of the plaintiff’s injury;

- Proximate cause: where liability is cutoff (foreseeability);

- Damages: the plaintiff suffered actual damages as a result of the negligent act.

Contract Law Basis for Product Liability

A warranty is a guarantee that a product meets certain standards of performance. In the United States, warranties are established by the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), a system of statutes designed to make commercial transactions consistent in all fifty states. Under the UCC, a warranty is based on contract law and, as such, constitutes a binding promise. If this promise—the promise that a product meets certain standards of performance—is not fulfilled, the buyer may bring a claim of product liability against the seller or maker of the promise.

- Express Warranties

An express warranty is created when a seller affirms that a product meets certain standards of quality, description, performance, or condition. The seller can make an express warranty in any of three ways:

- By describing the product

- By making a promise of fact about the product

- By providing a model or sample of the product

Sellers are not obligated to make express warranties. When they do make them, it is usually made through advertisements, catalogs, and so forth, but they do not need to be made in writing; they can be oral or even inferred from the seller’s behavior. They are valid even if they are made by mistake.

2. Implied Warranties

There are two types of implied warranties—that is, warranties that arise automatically out of transactions:

- In making an implied warranty of merchantability, the seller states that the product is reasonably fit for ordinary use. In selling a product, the merchant affirms that the product satisfies any promises made on its packaging, meets average standards of quality, and should be acceptable to other users.

- An implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose affirms that the product is fit for some specific use.

| Type of Warranty | Means by Which the Warranty May Be Created | Promises Entailed by the Warranty |

| Express warranty | Seller confirms that product conforms to:

|

Product meets certain standards of quality, description, performance, or condition |

| Implied warranty of merchantability | Law implies certain promises | Product:

|

| Implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose | Law implies certain promises | Product is fit for the purpose for which the buyer acquires it if

|

Source: Adapted from Henry R. Cheesman, Contemporary Business and Online Commerce Law: Legal, Internet, Ethical, and Global Environments, 5th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2006), 366.

Strict Liability

Strict liability is the third standard or basis that can be proffered for a claim of a defective product. In product liability cases based on negligence (see above), the plaintiff must prove that the defendant breached their duty, which implies fault. Strict liability imposes no such requirement for proof of fault. In a successful claim for strict liability, the defendant is liable for the harms caused regardless of fault. Strict liability applies in three categories of cases: 1) where the defendant keeps wild animals that cause injury, 2) where the defendant engages in abnormally dangerous activities (such as dynamite blasting, crop dusting, storing gasoline, etc.), and 3) certain product liability actions. The Restatement (Second) of Torts Section 402A summarizes how the law defines strict product liability.

402A. SPECIAL LIABILITY OF SELLER OF PRODUCT FOR PHYSICAL HARM TO USER OR CONSUMER

(1) One who sells any product in a defective condition unreasonably dangerous to the user or consumer or to his property is subject to liability for physical harm thereby caused to the ultimate user or consumer, or to his property, if

(a) the seller is engaged in the business of selling such a product, and

(b) it is expected to and does reach the user or consumer without substantial change in the condition in which it is sold.

(2) The rule stated in Subsection (1) applies although

(a) the seller has exercised all possible care in the preparation and sale of his product, and

(b) the user or consumer has not bought the product from or entered into any contractual relation with the seller.

Caveat:

The Institute expresses no opinion as to whether the rules stated in this Section may not apply

(1) to harm to persons other than users or consumers;

(2) to the seller of a product expected to be processed or otherwise substantially changed before it reaches the user or consumer; or

(3) to the seller of a component part of a product to be assembled.

3.5 Consumer Arbitration

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain arbitration with respect to consumer products

- Describe the problems associated with mandatory arbitration

Arbitration is a method of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) intended to encourage parties in a dispute to work it out outside of the court system. Congress has endorsed the public policy of encouraging arbitration, through passage of the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA). Passed in 1925, the FAA provides the legal principles applicable to arbitration in the U.S. The core principle of the FAA is that arbitration agreements involving foreign or interstate commerce must be considered valid, irrevocable, and enforceable (except on legal or equitable grounds for revocation of a contract). In other words, if two parties enter into an agreement to arbitrate a dispute, the U.S. government (to include the courts) takes the position that the agreement is enforceable unless either party can show that the contract should be unenforceable based upon principles of contract law or equity.

More and more consumer contracts contain clauses mandating that a dispute that could arise from a product purchase be resolved through arbitration. Due to the FAA and principles of contract law, courts are reluctant to not enforce agreements to arbitrate. The problem is that not all consumers are aware that they have agreed to arbitrate. When a consumer purchases an item from a website, they agree to the terms and conditions, which often includes a mandatory arbitration clause. These terms and conditions are also often not readily visible to consumers, requiring the consumer to click on a “terms and conditions” link on the bottom of the page.

The 2019 case of Nicholas v. Wayfair highlights the challenges consumers face when seeking resolution of defective products sold to them during a consumer transaction. The plaintiff purchased a headboard from Wayfair.com only to find bedbugs in her home. After failing to resolve the issue with Wayfair’s customer service, she filed a lawsuit seeking damages for having to debug her home through extermination. Wayfair, then moved to compel arbitration arguing that she voluntarily acceded to the terms when clicking on the “Submit Order” button under which was the text “By placing this order, you are agreeing to our terms and conditions,” that precluded her from filing a lawsuit against them. The terms and conditions contain the following:

YOU AND Wayfair AGREE TO GIVE UP ANY RIGHTS TO LITIGATE CLAIMS IN A COURT OR BEFORE A JURY OR TO PARTICIPATE IN A CLASS ACTION OR REPRESENTATIVE ACTION WITH RESPECT TO A CLAIM. OTHER RIGHTS THAT YOU WOULD HAVE IF YOU WENT TO COURT, SUCH AS ACCESS TO DISCOVERY, ALSO MAY BE UNAVAILABLE OR LIMITED IN ARBITRATION.

Any dispute between you and Wayfair, its agents, employees, officers, directors, principals, successors, assigns, subsidiaries or affiliates (collectively for purposes of this section, ‘Wayfair ’) arising from or relating to these Terms of Use and their interpretation or the breach, termination or validity thereof, the relationships which result from these Terms of Use, including disputes about the validity, scope or enforceability of this arbitration provision (collectively, “Covered Disputes “) will be settled by binding arbitration in Suffolk County, Commonwealth of Massachusetts administered by the American Arbitration Association (AAA) under its Commercial Arbitration Rules, in effect on the date thereof. Prior to initiating any arbitration, the initiating party will give the other party at least 60-days’ advanced written notice of its intent to file for arbitration. Wayfair will provide such notice by e-mail to your e-mail address on file with Wayfair and you must provide such notice by e-mail to [legal@wayfair.com].

During such 60-day notice period, the parties will endeavor to settle amicably by mutual discussions any Covered Disputes. Failing such amicable settlement and expiration of the notice period, either party may initiate arbitration. The arbitrator will have the power to grant whatever relief would be available in court under law or in equity and any award of the arbitrator(s) will be final and binding on each of the parties and may be entered as a judgment in any court of competent jurisdiction. The arbitrator will not, however, have the power to award punitive or exemplary damages, the right to which each party hereby waives, and the arbitrator will apply applicable law and the provisions of these Terms of Use and the failure to do so will be deemed an excess of arbitral authority and grounds for judicial review. Wayfair and you agree that any Covered Dispute hereunder will be submitted to arbitration on an individual basis only. Neither Wayfair nor you are entitled to arbitrate any Covered Dispute as a class, representative or private attorney action and the arbitrator(s) will have no authority to proceed on a class, representative or private attorney general basis. If any provision of the agreement to arbitrate in this section is found unenforceable, the unenforceable provision will be severed and the remaining arbitration terms will be enforced (but in no case will there be a class, representative or private attorney general arbitration). Regardless of any statute or law to the contrary, notice on any claim arising from or related to these Terms of Use must be made within one (1) year after such claim arose or be forever barred. For purposes of this section, these Terms of Use and related transactions will be subject to and governed by the Federal Arbitration Act, 9 U.S.C. sec. 1 – 16 (FAA).

The court found that the agreement was enforceable and granted Wayfair’s motion to compel arbitration on the basis of principles of contract law and public policy preferring arbitration over litigation. As can be seen from the language above, the terms and conditions are not easy reading and are understandably easily overlooked. However, these conditions can have consequences for the consumer that unwittingly agrees to abide by them.

Endnotes

Engineering Progress: The Revolution and Evolution of Working for a Safer World, Underwriters Laboratories (2016), https://www.ul.com/sites/g/files/qbfpbp251/files/2019-05/EngineeringProgress.pdf.

Elizabeth Sergan. ‘The Volume of the Problem is Astonishing’: Amazon’s Battle Against Fakes May Be Too Little, Too Late, FastCompany (2021), https://www.fastcompany.com/90636859/the-volume-of-the-problem-is-astonishing-amazons-battle-against-fakes-may-be-too-little-too-late

Federal Hazardous Substances Act Requirements, CPSC (n.d.), https://www.cpsc.gov/Business–Manufacturing/Business-Education/Business-Guidance/FHSA-Requirements

Flammable Fabrics Act, CPSC (n.d.), https://www.cpsc.gov/Regulations-Laws–Standards/Statutes/Flammable-Fabrics-Act.

Jennifer Schlesinger & Andrea Day, How the CPSC Keeps Consumers Safe From Products That Get Recalled, CNBC (2017), https://www.cnbc.com/2017/09/09/how-the-cpsc-keeps-consumers-safe-from-products-that-get-recalled.html

How to Spot Counterfeit Goods: The Six Warning Signs, INCOPRO, https://www.incoproip.com/how-to-spot-counterfeit-goods/

FY 2021 Annual Financial Report, CPSC (2021), https://cpsc-d8-media-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/FY-2021-US-CPSC-Agency-Financial-Report_1.pdf?VersionId=_OE75MjPtOteHnFmQ7y7lVBd1cyl__VY

Nicholas v. Wayfair, 410 F.Supp. 3d. 448 (E.D.N.Y. 2019).

Poison Prevention Packaging Act, CPSC (n.d.), https://www.cpsc.gov/Regulations-Laws–Standards/Statutes/Poison-Prevention-Packaging-Act.

The Ancient Maxim of Caveat Emptor, Walton Hamilton (1931).

Takata Corporation Agrees to Plead Guilty and Pay $1 Billion in Criminal Penalties for Airbag Scheme, Department of Justice (2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/takata-corporation-agrees-plead-guilty-and-pay-1-billion-criminal-penalties-airbag-scheme.