6

Chapter 6 Outline:

6.1 Consumer Credit

6.2 Payday and Predatory Loans

6.3 Financial Data and Disclosures

Introduction

According to the credit reporting agency, Experian, overall consumer debt in 2020 amounted to just under $14.8 trillion. That is more than all of the assets of the United States government ($6 trillion). Debt is not a new idea in the United States nor is it necessarily a bad one. Incurring debt enables us to purchase homes, cars, education, and countless other items in the present that we can pay for in the future. The system of capitalism is built in part on the extension of credit and the debt it creates. While there are federal and state laws and regulations that govern how lenders lend money and protections for consumers in repaying debts, as will be explored in this chapter, capitalism also seems to be built on a model of exploitation in the form of subprime and predatory lending practices. Consumers must be diligent in protecting themselves from falling into cycles of debt.

6.1 Consumer Credit

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the development and importance of credit

- Understand what a credit score is and how it is calculated

- Describe the contents of a credit report

- Describe what errors may be present in credit reports

The very idea of extending credit to someone so that person may purchase something only to pay back the lender is not a new concept. The idea of using a valueless instrument to represent a transaction dates back 5,000 years to the Indus Valley (Harappan) civilization, a bronze age civilization located in parts of modern day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India in existence from c. 3300 to c. 1300 BCE. Texts from ancient Mesopotamia, indicate the existence of clay tablets being used to record trade from members of the Indus Valley civilization. These clay tablets that contained the seals of both civilizations were a token of credit. Credit coins were used in the 19th century as a means of credit extension by merchants to farmers. Various advancements in the use of credit were found throughout the 20th century. The modern plastic credit card came about in 1959 with a card issued by American Express and in 1966 the Bank of America card with a revolving credit feature became the first credit card accepted in the continental United States. Three years later IBM invented the magnetic strip. Further advances in credit card security will be discussed in Chapter 8.

Credit rating agencies did not exist in the United States prior to 1864. Consumer credit worthiness traveled lender to lender by word of mouth until 1899. Today, there are three main credit reporting agencies: Equifax, TransUnion, and Experian. These agencies, along with others, essentially are in the business of collecting consumer data to give to lenders when the lenders are deciding how high the risk is for a potential borrower.

There are two main types of credit that an individual or business may take out: closed-end credit and open-end credit. Common types of closed-end credit includes mortgages and car loans. Both of these loans are taken out for a specific period of time during which the consumer is required to make payments. When financing an assed under closed-ended credit, the lender usually holds some ownership over the asset and can repossess it as compensation for the default, when the consumer fails to make payments. Open-end credit examples include credit cards and home-equity lines of credit (HELOC). The lender allows the consumer to utilize the credit in exchange for a promise to make payments. The amount a consumer may borrow depends on the credit score.

Credit Scores

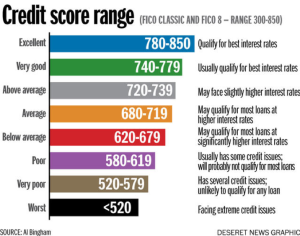

A credit score is a number, typically ranging from 300 to 850 that represents the risk a lender takes when they lend a consumer money, or from the consumer’s perspective how well they manage debt. The FICO score, created by the Fair Isaac Corporation, is the most widely used credit score. A credit score essentially acts as a financial label that indicates to lenders whether or not you should qualify for a loan. Consumers do not have just one credit score, rather FICO has dozens of credit score models for car loans, mortgages, and credit cards.

A single FICO credit score is comprised of credit data, from the credit report, grouped into five categories:

- Payment history (35%) – one of the most important factors in a FICO score. Lenders want to know if payments are made on time.

- Amounts owed (30%) – use of available credit may not mean you are a high-risk borrower, but using a lot of available credit may mean overextension and banks may interpret that to mean a higher chance of defaulting.

- Length of credit history (15%) – having older accounts is positive, but not required for a good credit score.

- New credit (10%) – opening several accounts in a short period of time may represent a higher risk.

- Credit mix (10%) – FICO considers the mix of credit cards, retail accounts, installment loans, finance company accounts, and mortgages.

Numerous third party websites give consumers the ability to easily check their credit scores on a regular basis without harming it. The credit reporting agencies (Experian, TransUnion, and Equifax) also provide the ability to check credit scores.

Credit Reports

A credit report is a summary of personal credit history that greatly impacts the ability for a consumer to make purchases. Some information in the credit report is used to calculate the credit score (as described above). A credit report will include 4 types of information:

- Personally Identifiable Information (PII)-This information is not used to calculate the credit score. PII includes the name, address, social security number, date of birth, and employment information used for identification.

- Credit accounts-Lenders report on accounts established, the type of account (credit card, auto loan, mortgage, etc), the date the account was opened, credit limit or loan amount, account balances, and payment history.

- Credit inquiries-lenders request credit reports when they receive a loan application. The inquiries section lists everyone who has accessed the credit report in the last two years. There are two types of inquiries. A soft inquiry is one in which a lender may order the credit report to send an offer of pre-approval. A soft inquiry does not impact the FICO credit score. Only the consumer can see soft inquiries on the credit report. A hard inquiry means that the consumer has requested credit. Multiple hard inquiries can negatively impact the FICO score as it is indicative of potential higher risk to the lender.

The Fair Credit Reporting Act

Congress passed the Fair Credit Reporting Act in 1970 to promote accuracy, fairness, and privacy of information in the files of consumer credit reporting agencies. The rights of consumers with respect to credit reporting may be summarized as follows:

- You must be told if information in your file has been used against you.

- You have the right to know what is in your file.

- You have the right to ask for a credit score.

- You have the right to dispute incomplete or inaccurate information.

- Consumer reporting agencies must correct or delete inaccurate, incomplete, or unverifiable information (usually within 30 days).

- Consumer reporting agencies may not report outdated negative information.

- Access to your file is limited.

- You must give your consent for reports to be provided to employers.

- You may limit “prescreened” offers of credit and insurance you get based on information in your credit report.

-

You have a right to place a “security freeze” on your credit report, which will prohibit a consumer reporting agency from releasing information in your credit report without your express authorization.

- You may seek damages from violators.

Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA)

Passed by Congress in 1974, this law prohibits creditors from discriminating against any applicant on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, marital status, age, public assistance the applicant may receive, or because they exercise a right under the Consumer Credit Protection Act. Under the ECOA, the Department of Justice can file charges against the creditor if they are found to have partaken in a pattern or practice of discrimination. An individual who believes they have been discriminated against during a credit transaction involving property, may filed a complaint with the Department of Housing Development (HUD) or file their own private lawsuit. Other federal agencies have the general authority to regulate certain types of lenders under the ECOA and are required to refer matters to the Department of Justice any of the agencies have reason to believe that a creditor is engaged in a pattern or practice of discrimination.

Credit Report Errors

Despite the FCRA’s role to promote accuracy and fairness, credit reports may contain errors that can negative impact the credit score. According to the non-profit Consumer Reports, more than one-third credit reports may contain errors. These errors can be disputed, though sometimes consumers may find it difficult to have certain errors corrected. The three most common errors are 1) mistakes in PII such as incorrect names and addresses, 2) credit accounts that do not belong to the consumer, and 3) accounts that were supposed to be in forbearance. However, sometimes an error can be much more severe and detrimental to the consumer. According to the Social Security Administration’s Office of the Inspector General, there are approximately 6,000 people who are inaccurately reported as dead per year. This can cause lenders to deny credit to any one of those “decease” people should they apply for it.

Some common errors in credit reports are:

Identity errors

- Errors made to your identity information (wrong name, phone number, address)

- Accounts belonging to another person with the same or a similar name as yours (this mixing of two consumers’ information in a single file is called a mixed file)

- Incorrect accounts resulting from identity theft

Incorrect reporting of account status

- Closed accounts reported as open

- You are reported as the owner of the account, when you are actually just an authorized user

- Accounts that are incorrectly reported as late or delinquent

- Incorrect date of last payment, date opened, or date of first delinquency

- Same debt listed more than once (possibly with different names)

Data management errors

- Reinsertion of incorrect information after it was corrected

- Accounts that appear multiple times with different creditors listed (especially in the case of delinquent accounts or accounts in collections)

Balance Errors

- Accounts with an incorrect current balance

- Accounts with an incorrect credit limit

If you find errors, you should contact the credit reporting company who sent you the report, and the creditor or company that provided the information (called the “furnisher” of the information). Your credit report includes directions about how to dispute inaccurate or incomplete information or you can use sample dispute letters for furnishers and credit reporting companies.

Source: What are Common Credit Report Errors That I Should Look For on my Credit Report?, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (2020), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/what-are-common-credit-report-errors-that-i-should-look-for-on-my-credit-report-en-313/.

6.2 Predatory Loans

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify types of predatory lending practices

- Describe payday loans

Payday loans, loans meant to be paid back on the consumer’s next payday, and other types of loans made in an unethical manner by lenders are all too common in the United States. This section will discuss a few of the types of lending practices that can be considered predatory.

- Equity Stripping

The lender makes a loan based upon the equity in your home, whether or not you can make the payments. If you cannot make payments, you could lose your home through foreclosure. - Bait-and-switch schemes

The lender may promise one type of loan or interest rate but without good reason, give you a different one. Sometimes a higher (and unaffordable) interest rate doesn’t kick in until months after you have begun to pay on your loan. - Loan Flipping

A lender refinances your loan with a new long-term, high cost loan. Each time the lender “flips” the existing loan, you must pay points and assorted fees. - Packing

You receive a loan that contains charges for services you did not request or need. “Packing” most often involves making the borrower believe that credit insurance must be purchased and financed into the loan in order to qualify. - Hidden Balloon Payments

You believe that you have applied for a low rate loan requiring low monthly payments only to learn at closing that it is a short-term loan that you will have to refinance within a few years. (source: Washington State Department of Financial Institutions, https://dfi.wa.gov/financial-education/information/predatory-lending).

James v. National Financial LLC (Del. Ch. 2016)

Gloria James is a resident of Wilmington, Delaware. From 2007 through 2014, James worked in the housekeeping department at the Hotel DuPont. In May 2013 James earned $11.83 per hour. As a part-time employee, her hours varied. On average, after taxes, James took home approximately $1,100 per month. James’ annualized earnings amounted to roughly 115% of the federal poverty line, placing her among what scholars call the working poor. Contrary to pernicious stereotypes of the poor as lazy, many work extremely hard. James exemplified this attribute. She got her first job at age thirteen and has been employed more or less continuously ever since. Her jobs have included stints in restaurants, at a gas station, as a dental assistant, as a store clerk, and at a metal plating company. In 2007, she obtained her position with the Hotel DuPont. She was laid off on December 31, 2014, when the hotel reduced its part-time staff.

James is undereducated and financially unsophisticated. She dropped out of school in the tenth grade because of problems at home. Approximately ten years later, she obtained her GED.

Around the same time, she obtained her position with the Hotel DuPont, James attempted to improve her skills by enrolling in a nine-month course on medical billing and coding. For seven months, she worked from 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. at the hotel, then attended classes starting at 5:00 p.m. She was also taking care of her school-age daughter. Two months before the end of the program, the schedule became too much and she dropped out. James thought she received a grant to attend the program, but after dropping out she learned she actually had taken out a student loan. She eventually repaid it. James does not have a savings account or a checking account. She has no savings. She uses a Nexis card, which is a pre-paid VISA card.

In May 2013, James had been using high interest, unsecured loans for four to five years. She obtained loans from several finance companies. She used the loans for essential needs, such as groceries or rent. On at least one occasion, she used a loan from one provider to pay off an outstanding loan from another provider. James had obtained five prior loans from National. James believed that she repaid those loans in one or two payments. The payment history for the loans shows otherwise.

In May 2013, National Financial LLC, a payday loan company, loaned $200 to Gloria James. National described the loan product as a “Flex Pay Loan.” In substance, it was a one-year, non-amortizing, unsecured cash advance. The terms of the loan called for James to make twenty-six, bi-weekly ,interest-only payments of $60, followed by a twenty-seventh payment comprising both interest of $60 and the original principal of $200. The total repayments added up to $1,820, representing a cost of credit of $1,620. According to the loan document that National provided to James, the annual percentage rate (“APR”) for the loan was 838.45%.

On May 8, 2013, the day after obtaining the loan, James broke her hand while cleaning a toilet at the Hotel DuPont. After missing an entire week of work, she asked her supervisor to allow her to return because she could not afford to remain out any longer. As James explained at trial: “I don’t get paid if I don’t work.” Her supervisor agreed that she could work two or three days per week on light duty. On May 17, 2013, James went to the Loan Til Payday store and made the first interest payment of $60. She spoke with Brian Vazquez, the store manager. She told him that she had broken her hand and would not be able to work, and she asked him to accommodate her with some type of arrangement. Vazquez told her that she would have to make the scheduled payments and that National would debit her account if she did not pay in cash. Vazquez then suggested that James increase her payment from $60 to $75. James was nonplussed and asked him, “How can I pay $75 if I can’t pay $60 interest.” Vazquez responded that being able to work fewer hours was not the same as losing her job.

In the above case, Gloria James was able to obtain help through a legal clinic to file a lawsuit against National Financial in a Delaware chancery court. The Court found for James, holding that the contract she signed for the payday loan was unconscionable. The doctrine of unconscionability is a rarely invoked way to hold a contract unenforceable as contrary to public policy. Courts generally favor the freedom of contract, which means that people are free to contract with certain legal limits depending on the industry and the principles of contract law. Thus, to render a contract unenforceable typically requires exceptional circumstances.

Predatory Borrowing?

Critics of blaming only the lenders for predatory practices point out that borrowers may also partake in predatory practices. Borrowers taking on a loan, such as a mortgage, that was too much for them to handle financially (and aided some by hard to understand disclosures and hidden terms that make a mortgage seem more affordable than it really is), seems to have at least contributed to the housing market crash of 2008. This perhaps bolsters the argument that some borrowers are to blame and may have no business taking out loans they cannot afford to pay back. Payday loan borrowers sign the contracts perhaps with some knowledge of how bad they really are, but knowing how bad they are does not pay the bills. According to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 3 out of 4 payday loans go to borrowers that take out 10 or more loans per year. Consequently, payday loans cost 12 million Americans more than $7 billion a year, with $4 billion alone in fees.

6.3 Financial Data and Disclosures

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand the concept of “mandated disclosure”

- Identify the key information in a “Schumer Box”

Whenever a consumer borrows money or is in another way extended credit, numerous federal and state laws mandate that the lenders give the consumer specific information with respect to the terms and conditions of the contract. These laws are based on the concept of “mandated disclosure,” which has served as the lynchpin for legislation designed to provide consumers with the information they need to make the appropriate decision.

One such legislative measure, introduced by then Representative Charles Schumer of New York, requires disclosure of the important terms and conditions for credit card offers.

Truth in Lending Act (TILA)

Another important piece of legislation, the Truth In Lending Act (TILA) requires creditors who deal with consumers to disclose information in writing about finance charges and related aspects of credit transactions, including finance charges expressed as an annual percentage rate. In addition, the Act establishes a three-day right of rescission in certain transactions involving the establishment of a security interest in the consumer’s principal dwelling (with certain exclusions, such as interests taken in connection with the purchase or initial construction of a dwelling). The Act also establishes certain requirements for advertisers of credit terms.

Endnotes

Christina Majaski, Closed-End Credit vs. an Open Line of Credit: What’s the Difference?, Investopedia (2021), https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/062915/what-difference-between-closed-end-credit-and-line-credit.asp.

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act, Department of Justice (2021), https://www.justice.gov/crt/equal-credit-opportunity-act-3.

Meredith Hoffman, The History of Credit Cards, Bankrate (2021), https://www.bankrate.com/finance/credit-cards/the-evolution-of-credit-cards/.

What’s in My FICO Scores?, MyFICO (n.d.), https://www.myfico.com/credit-education/whats-in-your-credit-score

Will Kenton, Truth-in Lending Act, Investopedia (2021), https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/tila.asp.

Bill Fay, What is Predatory Lending?, Debt.org (n.d.), https://www.debt.org/credit/predatory-lending/.