5

Chapter 5 Outline:

5.1 Deceptive Advertising

5.2 MLM-Legitimate Scheme or Pyramid Scheme?

5.3 Ponzi Schemes

5.4 Scams and Robo Calls

Introduction

Advertising in the United States is a multibillion dollar industry, with expenditures amounting in 2019 to over $240 billion. Advertising can take on many forms to include television, internet, print, outdoor, mobile, radio, and film. With the amount of money spent on advertising and the number of outlets for it, it is safe to say that consumers are flooded with advertising on a daily basis. Therefore, the government, in particular the FTC, as well as state governments, have a strong interest in ensuring ads are not deceptive and misleading.

5.1 Deceptive Advertising

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the FTC’s definition of an unfair deceptive act or practice (UDAP)

- Explain the difference between fact, opinion, and puffing

- Discuss the deception of MyPillow

The Federal Trade Commission Act allows the FTC to act in the interest of all consumers to prevent deceptive and unfair acts or practices. In interpreting Section 5 of the Act, the Commission has determined that a representation, omission or practice is deceptive if it is likely to:

- mislead consumers and

- affect consumers’ behavior or decisions about the product or service.

In addition, an act or practice is unfair if the injury it causes, or is likely to cause, is:

- substantial

- not outweighed by other benefits and

- not reasonably avoidable.

The FTC Act prohibits unfair or deceptive advertising in any medium. That is, advertising must tell the truth and not mislead consumers. A claim can be misleading if relevant information is left out or if the claim implies something that’s not true. For example, a lease advertisement for an automobile that promotes “$0 Down” may be misleading if significant and undisclosed charges are due at lease signing.

In addition, claims made in the ads must be substantiated, especially when they concern health, safety, or performance. The type of evidence may depend on the product, the claims, and what experts believe necessary. If the ad specifies a certain level of support for a claim – “tests show X” – the advertiser must have at least that level of support.

Sellers are responsible for claims they make about their products and services. Third parties – such as advertising agencies or website designers and catalog marketers – also may be liable for making or disseminating deceptive representations if they participate in the preparation or distribution of the advertising, or know about the deceptive claims.

The FTC has the authority to file lawsuits against companies that make false claims in advertisements. For example, in October 2021, the FTC filed suit against Xlear, Inc., for alleged violations of the COVID-19 Consumer Protection Act and the FTC Act. Passed by Congress in December 2020, the COVID-19 Consumer Protection Act prohibits deceptive acts or practices with respect to the treatment, cure, prevention, mitigation, or diagnosis of COVID-19. According to the lawsuit, since March 2020, Xlear marketed and sold “Xlear Saline Nasal Spray with Xylitol” as prevention and treatment of COVID-19 without competent and reliable scientific evidence that Xlear Nasal Spray treats or prevents COVID-19.

Fact or Opinion or Puffing?

False advertising is one of the most common claims brought by a consumer. As described above, truth is central to advertising. Truth can come in the form of facts or opinions. If the advertiser makes a factual claim, such as that the pillow can cure diseases, they must be able to prove that scientifically. If the advertiser makes that claim that their pillow is the most comfortable pillow that consumers will ever use, that is an opinion, which could be considered puffing. An advertisement that contains puffing is one in which, in general terms, the product or service is superior. Some classic product slogans considered puffing are: “BMW: the ultimate driving machine,” “Maxwell House: good to the last drop,” or “Miller Lite: taste great, less filling.” These statements are general enough to not be misleading. However, also as seen above, there can be a fine line between facts, opinion, or puffing.

Lanham Act False Advertising

A claim of false advertising can also be brought by a competitor of a business against another business. Under the Lanham Act (a federal law governing trademarks, unfair competition, among other things), the plaintiff must show:

- The ads of the opposing party were false or misleading;

- the ads decieved, or had the capacity to deceive consumers;

- the deception had a material effect on purchasing decisions;

- the misrepresented product or service affects interstate commerce; and

- the movant has been-or is likely to be injured as a result of the false advertising.

My Pillow

In addition to the FTC, states also can enforce their own deceptive act or practice laws. In 2016, the state of California filed a lawsuit against Minnesota based pillow company, MyPillow, alleging multiple violations of California advertising laws for airing misleading TV commercials. In the commercials, MyPillow claimed that the pillows could “help with” or improve the symptoms of a variety of conditions, including but not limited to fibromyalgia, insomnia, migraines, Temporomandibular Joint Disorder (TMJ), restless leg syndrome (RLS), sleep apnea, and snoring. These claims were not supported by “competent and reliable scientific evidence.” The lawsuit filed by California resulted in MyPillow and the State agreeing to a stipulated judgment and injunction. MyPillow was prohibited from making unsubstantiated claims about the health benefits of its pillows. Under the stipulated judgment MyPillow could make claims about the health benefits of its pillows, so long as it did so by using an “adequate and well-controlled human clinical study.”

In November 2018, MyPillow started airing TV commercials that promoted the benefits of using their pillows, this time claiming that their pillows were clinically proven to help with a variety of conditions. According to the advertisement, the double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled sleep study proved the benefits of their pillows. California disagreed, and filed a lawsuit alleging MyPillow violated the 2016 stipulated judgment and injunction, the terms of which they had agreed to abide by.

According to California, the sleep study was not double-blind. In a true double-blind study, neither the participant nor the administrator knows what pill or product is being tested and which is the placebo. In the “sleep study” the treatments in question were completely distinguishable since the MyPillow was stuffed with foam and the goose down pillow stuffed with feathers. The participants could easily distinguish between the pillows, and according to the study itself, many participants refused to switch to the placebo down pillows, which is an obvious sign that the participants could tell between the two products, defeating the claim that the study was double blind.

The “sleep study” and supporting advertising campaign were false and misleading in other ways. The advertisement claimed that 100 % of the participants of the study increased their amount of deep sleep with MyPillow. The study however did not find that claim to be true, and midway during the advertising campaign, MyPillow changed their claim to say that there was a “significant increase in the amount of sleep.”

The sleep study was also executed in a highly flawed manner. The pool of participants consisted of adults over the age of 50 from Brooklyn who were primarily of Russian ethnicity. The study did not disclose this fact nor provide any scientific rationale. As a result of the evidence presented that MyPillow violated the stipulated agreement, MyPillow agreed to pay $100,000 in civil penalties to settle the lawsuit filed by California.

5.2 MLM-Legitimate Scheme or Pyramid Scheme?

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe what an MLM is

- Discuss how an MLM differs from a Pyramid Scheme

Multi-Level Marketing (MLM) refers to a strategy used by some direct sales companies, such as Amway, Beauty Counter, LuLaRoe, and Herbalife to sell products or services. The MLM as a business model is predicated on the continuous recruitment of participants, who unbeknownst to most are really the customers. In the MLM model, distributors are the non-salaried workforce that can in theory earn profit from the commission of the items they sell. These companies make convincing presentations to people who seek higher income, flexibility, and perks as the owners of their own business. Herbalife and other MLM’s entice people to become distributors by making it seem like you will be starting your own business where you can be your own boss, set your own hours, sell quality products with low start-up costs, and of course, make lots of money. This however, is far from reality.

According to a report published by the FTC based on a study of 350 MLMs, 99% of people who joined an MLM lost money. In order to sell, the distributor, or consultant, as they are sometimes referred to, must keep investing what little they may actually earn back into their inventory. MLMs will often turn the lack of profit back onto the consultant by saying that they did not try hard enough or did not want it badly enough. In the recent documentary, LulaRich, Mark Stidham, co-founder of LuLaRoe said, “we’re not in the clothing business, we’re in the people business.” In other words, the clothing does not matter as is evidenced by the poor product quality. But the people, sometimes stay at home mothers, having to pay $5,000 to $10,000 for the “start-up” costs, do matter.

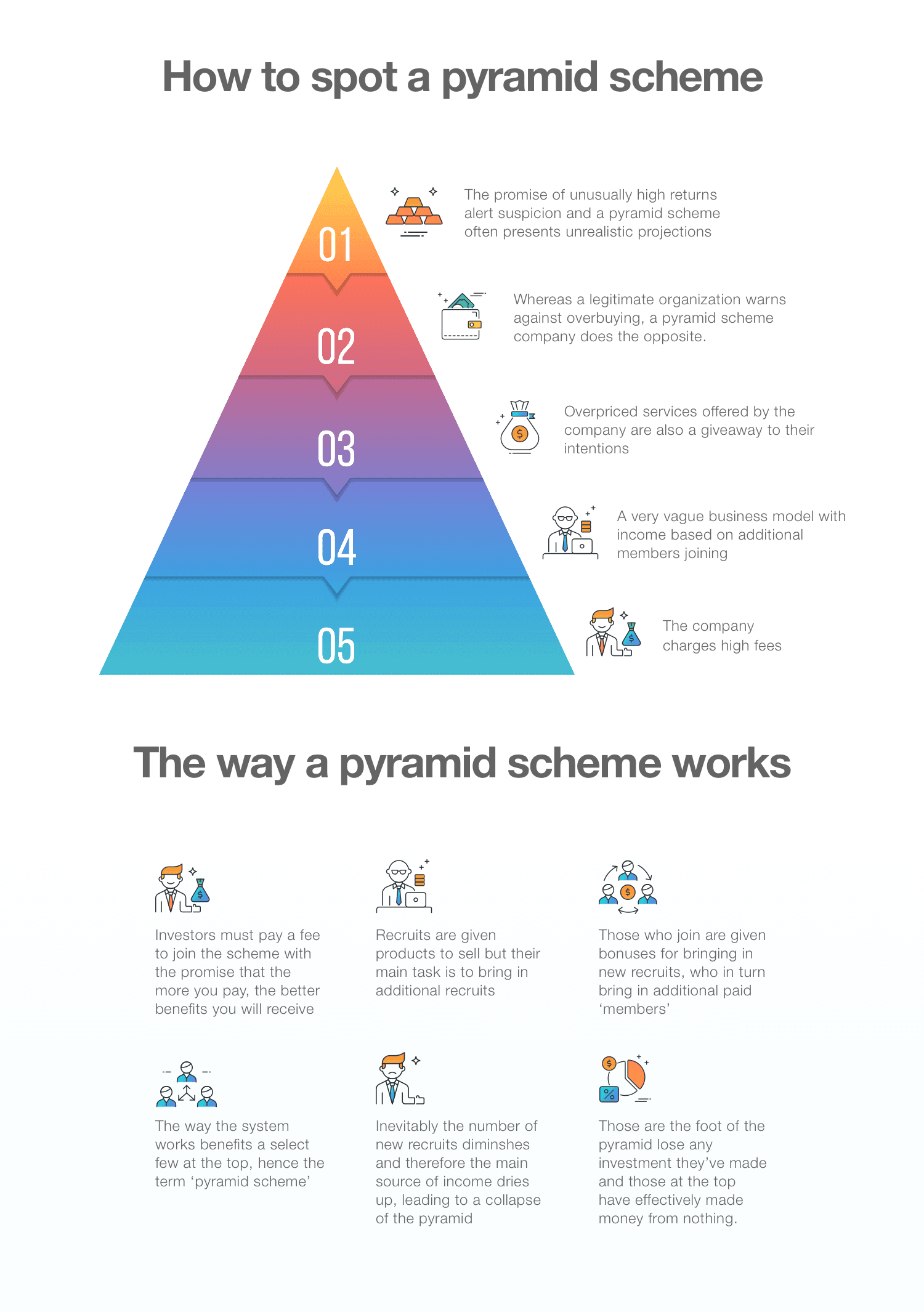

While not all MLMs are pyramid schemes, detecting the difference may be difficult. A pyramid scheme is one in which the schemer promises consumers or investors large profits based primarily on recruiting others to join, not based on profits from any real investment or product sales. The first telltale sign that a business opportunity is really a pyramid scheme is inventory loading. The company’s incentive structures are based around forcing recruits to buy more products than they can sell. The second telltale sign may be the lack of sales. Many schemes may claim high sales, but the sales may only primarily occur between people inside the pyramid structure or to new recruits.

5.3 Ponzi Schemes

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe how a Ponzi scheme works

- Discuss the difference between Pyramid and Ponzi scheme

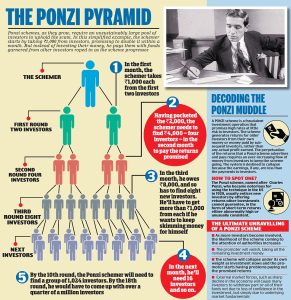

A Ponzi scheme is closely related to a pyramid scheme due to revolving around continuous recruiting, but in a Ponzi scheme the promoter has no product to sell and does not pay commission to investors who recruit new members. Rather, the promoter collects payment from streams of people, promising them a high rate of return for their short-term investments. However, in a Ponzi scheme, there is no investment. Rather the schemer, just uses some of the money to pay out some obligations owed to longer-standing members, to keep them satisfied. The expression “robbing Peter to pay Paul” fits the description of a Ponzi scheme nicely.

Named after Charles Ponzi, who became notorious for the scheme in the 1920s, others that came after him have used the scheme to dupe people into “investing” millions of dollars. Bernie Madoff perpetrated the largest Ponzi scheme in history in which he defrauded thousands of investors out of nearly $65 billion. Madoff pled guilty in 2009 to 11 felonies including, securities fraud, wire fraud, mail fraud, money laundering, making false statements, perjury, theft from an employee benefit plan, and making false filings to the SEC. Madoff was sentenced to 150 years in prison and died in prison in 2021 at the age of 82.

Ponzi schemes have common characteristics. Some warning signs include:

- High returns with little not risk

- Overly consistent returns

- Unregistered investments

- Unlicensed sellers

- Secretive, complex strategies

- Issues with paperwork

- Difficulty receiving paperwork

5.4 Scams and Robocalls

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe how scammers avoid the National Do Not Call Registry

- Identify what a robocall is

Scammers from around the world use the internet to call consumers. The National Do Not Call Registry was created to prevent sales calls from real companies by telling telemarketers what numbers to not call. It does not prevent calls from scammers that ignore the registry. Thus, the best methods for avoiding scam or robocalls are call blocking and call labeling. The type of blocking or labeling used depends on the phone used (cell, landline, or voice-over IP).

One of the best ways to block calls on a cellphone is to download a call-blocking app. Additional ways include looking to see what built-in call blocking features the cellphone contains and what services the cellphone service provider may offer.

A robocall is a recorded message instead of a live person. If that robocall contains a message attempting to sell something to the consumer, that call may be illegal unless the company obtained written permission to contact the consumer in that way.

Endnotes

California Sues MyPillow For Deceptively Advertised Sleep Study Following TINA.Org Complaint, Truth-In-Advertising.org (2019), https://www.truthinadvertising.org/california-sues-mypillow-for-deceptively-advertised-sleep-study-following-tina-org-complaint/

Enforcement Policy Statement on Deceptively Formatted Advertisements, FTC (n.d.), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/896923/151222deceptiveenforcement.pdf

FTC Sues Utah-based Company for Falsely Claiming Its Nasal Sprays Can Prevent and Treat COVID-19, FTC (2021), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2021/10/ftc-sues-utah-based-company-falsely-claiming-its-nasal-sprays-can.

Michael Kim, Advertising: When Does “Puffing” Become False and Misleading?, CKB Vienna (2017), https://www.ckbvienna.com/blog/2017/2/20/advertising-when-does-puffing-become-false-and-misleading

Multi-Level Marketing Businesses and Pyramid Schemes, FTC (2021), https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/articles/multi-level-marketing-businesses-and-pyramid-schemes.

Ponzi Scheme, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (n.d.), https://www.investor.gov/protect-your-investments/fraud/types-fraud/ponzi-scheme

Robocalls, FTC (2021), https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/articles/robocalls