10

“At the end of the day, the most overwhelming key to a child’s success is the involvement of parents.”

—Jane D. Hull

Desired Outcomes

This chapter and the accompanying recommended readings and activities are designed to further develop educator trauma-informed competencies as demonstrated by:

- An awareness of the role of a student’s family in the successful implementation of TISP by including parents or guardians on various strategic planning committees and addressing their training and support needs in short, intermediate, and long-term goal processes

- Providing training and support to caretakers congruent with their role, and being mindful of enlisting licensed trauma-informed systems-trained mental health professionals to partner with TISP strategic planners

- Envisioning how to invite TISP-oriented parents into classroom settings as not merely classroom volunteers, but co-facilitators in providing safety and stabilization, reflecting the classroom as a secure base

Key Concepts

This chapter provides recommended guiding principles for licensed mental health professionals (LMHPs) facilitating TISP orientation programs for parents and guardians desiring to know more about TISP and/or desiring to volunteer as classroom or school aides. It is also intended to serve Strategic Planning Teams as goals are designed to include parents in TISP processes. It includes the following key concepts foundational to addressing the Community level of system change, namely parent and guardian involvement:

- The recognition of the educator’s scope of practice while advocating to include parents as co-facilitators

- Enlisting licensed mental health providers trained in a systems-based approach to trauma-informed mental health services (such as marriage and family therapists or other systems-trained providers) familiar with TISP in order to ensure the provider’s trauma-informed competencies and congruence with how the education setting is implementing its trauma-informed approach

- A holistic view of the nature of the problem contributing to student dysregulation and academic struggle that does not pathologize or scapegoat parents or guardians

Chapter Overview

In Section II, we addressed the tasks of the District Strategic Planning Team, including its responsibilities to include parents in the training process and to utilize community resources, in this case LMHPs, to assist with parent processes. In this chapter we address the District’s responsibility to orient parents to TISP, in partnership with LMHPs who will help design the parent orientation process as well as facilitate parent trainings. The Educator does not hold responsibility to provide orientation and training for parents, but is asked to review this chapter to remain aware of the tasks of the larger system.

Throughout our process thus far, we have emphasized two key themes regarding students and their families:

- Do not scapegoat parents as the source of the student’s dysregulation, as to do so represents a misunderstanding of the complexity of the problem; and

- For TISP to be successful, we must recognize that parents and guardians are partners with us in this process.

In this chapter we address how to include parents in TISP orientation and training processes. We are primarily addressing LMHPs who will partner with schools on Strategic Planning Teams to include parents. But we want educators to peek into the world of systems’ therapists so you can better understand how they will prepare parents to serve as classroom aides or simply have curiosity about your TISP processes in the classroom. Just as educators are adjusting the lens through which we see our students, we begin with the lens that LMHPs embrace in our work with families.

What often separates a good movie or novel depicting human drama from a mere story is when our main heroes and villains are presented in their full complexity—those stories where no one person is pure evil or pure good. Such stories often start by capturing our empathy and outrage on behalf of a suffering or traumatized character, and we become fully engrossed in discharging our anger and disapproval at the villain. But, as we peek into the villain’s life or internal thinking processes, we are moved to great empathy on their behalf as well, whether the story’s events invite us to hold firm in our disgust at their behavior or the plot invites us to rethink right and wrong. The movie The Cider House Rules explores this very issue with each character presented in their complexity (Hallstrom & Gladstein, 1999). This aspect of our experience is also captured in the State domain of neural functioning (Figure 2.5).

So it is with the story of trauma-informed care as applied to the education environment. When the story first opened, we all felt great empathy and outrage on behalf of students, who we learned most often come from homes with significant stress and disruption regardless of the parents’ education, race, or socioeconomic background. As we moved deeper into their stories and learned about ACE data, right on cue, many of us felt anger directed toward their families and envisioned an antidote of simply fixing the parents. We hope that this text is helping you see the fullness of what it means to be trauma-informed; there is great complexity, but there are also logical, practical signposts along the way to make sense of it all. And while we cannot deny that there is much collateral damage that is ultimately the reason we are writing this text—damage to students, to society, and more—there is also reason for great hope.

But for our sign posts—our conceptual framework—to make sense, we need to expand our own internal schemas. We cannot problem solve unless we can access schemas for categorizing and hierarchically arranging information in our brain. Piaget and Vygotsky explain in great detail how this cognitive process works. Much of our adult continuing education is all about learning how our sorting and arranging processes constantly need to be informed by new or updated schemas. We can’t forgo that internal mentalization; it simply needs system updates now and then.

And so it is with popular schemas regarding the nature of student academic and social functioning struggles. There is no doubt that TISP is upending traditional and postmodern notions of good pedagogy. But we are also attempting to do a little bit of course correction in regard to trauma-informed principles as applied to the school setting. A simple approach to what is ailing students today is often reflected in those narratives that give us basic cause-effect answers: “If there is trauma in a student’s background, it is usually the parents’ fault; that student will not be able to function and is doomed to lifelong struggle.” End of story. Even if it were that simple, that answer, in and of itself, stands to cause further rupture between parents and their children, further perpetuating unmitigated stress and trauma, all but ensuring its toxic effects causing further harm to the next generation. We’ve invited a slight tweak to this equation designed to inspire safety, trust, and hope among all of us who have ever relationally hurt or failed another, yet desire to not cause others pain. That’s just about all of us!

We have unpacked the complexity of trauma and the ways we can maximize resilience, even as we are fragile and easily harmed and scarred. And we have alluded to the dangers, as well as the half-truths, embedded in the concept of blaming or scapegoating parents as the source of the problem. Our students and parents are part of an epic story with much complexity! We all inherited a mess of some kind or another for which we are responsible. We didn’t ask for it, but there it is. We carry the pain of our ancestors in our bones, or we were on the receiving end of neglect or abuse from our own families that left indelible marks on our psyches, and no one can work at responding to these pains and healing those injuries but us. We are all accountable for our choices, even if accountability starts with the simple statement “I can’t stop myself—help!”

While blame is a natural response to watching someone actively hurting another person, in this case a child, there is a subtle difference between blame and holding one another accountable. We are attempting to deeply understand what it means to affirm each person’s ability to be responsible and accountable without negating their personhood in all its complexity, so we can avoid lacing our interventions with shame and judgment.

In this chapter, we are going to unpack this concept a bit further as we focus on parents as co-facilitators of TISP. Our hope is to broaden our empathy to include parents as we prepare them to serve as resources in the classroom or merely satisfy their curiosity about TISP.

The Challenge Embedded in Our Agenda

One of our goals with parents is to dispel the myth that they, as parents, are 100% weak bad seeds, or inadequate adults beyond hope or the ability to change. “If I had better character, I would have made better choices; if I had better self-control, I would have resisted this bad habit; if I had more motivation, I would not be in this mess.” Such cause-and-effect thinking assumes that we fully understand what is driving our intense need states (thoughts, feelings, and sensations signaling deeper beliefs and needs that are so intense, we just want to fix them or forget about them as soon as possible). And it assumes that we have access to a wider range of internal and external resources needed to make health-promoting choices. The proverbial “snap out of it” doesn’t work when we can’t sort out the internal traffic jam or know how to access reliable help along the way. We all can make better choices, break bad or harmful habits, and unlock motivation (which is a chemical soup, not something we can just decide to have on any given day). But the process of getting there, the process of seizing responsibility for our lives, means listening to our need for emotional and physical safety and connection first, and trusting this unlocks the door to a whole set of additional options we didn’t know existed.

I (Anna) love listening to exercise motivators, those persons who cheer (or cajole, order, or shame) you to get yourself to that gym and suffer through these grueling workouts that will lead you to nirvana. This is effective for people whose neurochemistry is working just well enough to inspire the initial trust that something good awaits them if they dare. And those who stick with it most often feel the whole world open up to them in that runner’s high that may kick in during or shortly after a workout. “Everybody should be doing this!” they exclaim.

Well, not everyone has that little kick of dopamine needed to inspire hope and then the pursuit of that activity. And not everyone gets the feel-good endorphins during or after a workout. The thought of such activities may create sludge in their brains and lead in their feet. They feel nothing but misery during and well after. The benefits are there, but much delayed—too much delayed for many, as the benefit of today’s discomfort shows up days later, and the cause-effect relationship loses its motivating potential.

A different tactic is needed for those of us who are unmotivated and paralyzed by a routine, health practice, or activity in pursuit of a goal. This dynamic shows up in the choices we make to meet intimacy or financial needs, to practice self-care in going to bed on time or saying no to too much screen time, to fulfilling social obligations such as holding our tongue and temper, to being kind to a coworker or a family member despite being exhausted, to resist taking our rage out on invisible persons on the internet or that driver next to you on the freeway. Every choice we make in response to the demands of every waking hour, whether it is our own internal needs or the expectations of the social world, is influenced by our neurochemistry as it then reverberates throughout our body. It messes with our sense of right and wrong, of entitlement verses self-advocacy, of empathy toward the need states of others, leading to all sorts of justifications for acting in ways that, at the end of the day, are hurtful to self and/or others.

We can act in life-giving ways in spite of this internal traffic. And it begins with insight and compassion, the best tools for playing chess with the way our stressed brains speak to us, messing with our thoughts, feelings, and perceived choices. If I want to maximize my health, prepare to get a job, keep a job, raise my children, break an addiction, I have to find a way to do x, y, and z despite the fact that I have sludge and lead holding me down or yanking my chain with impulsive quick fixes. And step one is to anchor myself, to connect, whether internally through mindfulness practices (or whatever term you choose), or through connection with safe, caring others. If I can relax into the discomfort with compassion and curiosity, I will be able to find the reserves I need to tolerate discomfort until I sort it out, finding little breaks along the way, little spaces of joy and a lessening of the weight of the world in blue-sky moments. I will find the resources or ideas either from my own brainstorming processes or in the presence of others who can brainstorm along with me.

And that is what it comes down to: Our stressed brains feel discomfort that is disproportionate to the tasks before us, and we need to not just find the reserves to tolerate it, but find ways to empathically understand it while seeking solutions—the ultimate way to tame its intensity. Trauma-informed knowledge is explaining what that sludge and lead looks like on a biological level, and why solutions need to start with safety and stabilization as the primary tools in response, the themes and goals of Connecting and Coaching.

This is what TISP schools are helping students learn, and as we unpack this with parents, it is what we will be teaching them as well. You may never get a runner’s high, and your child may always be bored to tears by social science class, but we can all learn how to listen to that discomfort, lean into it with compassion, and find a reason to tolerate the discomfort for a greater good or goal that inspires hope. Frustration tolerance and delayed gratification then have meaning and purpose that are important to us, and with practice—lots of practice and reinforcement through strong connections—the discomfort lessens and is easier to hold until, one day, it doesn’t take so much effort to do the basics, opening up space for us to invest more in the things that matter most to us with greater ease. This is what we get to see with students: the building blocks of learning how to ride various internal and interpersonal challenges with greater confidence that they can do this, even if it means stumbling around at times.

As we talk about including parents, we need to remember that for those parents interested in learning more, this is the process we are inviting them into, the same process we highlight in the Person of the Educator work; we are all touched by these themes, as none of us escape the challenge of making sense of life when it throws us stressful and traumatic curveballs. Here, we are breaking this process down, examining a way to invite parents into this process according to their interest and window of tolerance. We are not looking for overwhelming interest, although that does happen. We are looking for a cadre of parents who long for greater connection and partnership with their children’s school on behalf of their children, and perhaps their own inner desire to be more connected in their community, and ultimately grounded in their own lives. We will take each parent where they are; it’s all good!

Designing TISP Parent Orientation and Training Programs

The following provides guiding principles for designing and implementing TISP parent orientation and training programs. The title and content of such programs are up to each facilitator to discern. Rather, this chapter intends to provide a conceptual guideline for school and mental health professionals collaborating to include parents in the school’s TISP approach as well as prepare parent school aides.

Rationale

TISP proposes that all members of the school community should be included in the TISP orientation and training processes. This includes parents and guardians for four interrelated reasons:

School Programming Transparency. TISP asks schools to update their conceptualization and practices according to trauma-informed data regarding the nature of unmitigated stress and trauma and their impact on brain development and executive functioning central to learning. Parents and guardians are a part of the school community, and they have a right to not only understand the culture and ethos of their child’s school, but to participate in TISP orientations, just as all other school community members are encouraged to do.

Home and School Partnership. TISP posits that attunement and mentoring are key to building the neural networks needed to learn the academic and social-behavioral tasks of the K-12 years. We also know that parents have the greatest impact on a child’s sense of well-being. The more parents understand and can practice TISP methods in the home, the greater chance a student has of benefiting from a TISP approach to learning.

Parental Right to Know the Science. Professionals, such as educators, participating in trauma-informed training are learning what all of us deserve and need to learn: We have increased scientific data explaining why so many of us suffer and struggle in response to our own unintegrated neural networks. For many, it is an accumulation of biological vulnerabilities we came into this world with, the wounds of unmitigated stress and trauma from our ancestors, combined with the suffering of our caretakers, contributing to our own encounters with adverse childhood experiences. This is the environment in which our own strengths and limits were born and nurtured, including the intensity of various internal need states, even as our responses to these needs are washed through our thoughts and beliefs about self and the world. Despite the complexity of these challenges, we have proven strategies for how we can responsibly act in response to our own histories and current states of dysregulation. And when we seize those tools, we can attune and mentor the next generation—our own children, our students—thereby stopping the generational transmission process. Whether a parent wants to volunteer in the classroom or not, they deserve to learn ways to protect their children.

The Need for TISP-Trained Parents in the Classroom. TISP in the classroom and broader school environment will not be successful unless schools are adequately staffed with adults occupying a variety of roles. Most specifically, teachers need TISP-trained parent volunteers to provide attunement and mentoring in the classroom. In many instances, the presence of additional adults in the classroom is due to class size. However, regardless of class size, students need access to more adults throughout the school day to personally attune to their challenges and respond in a caring, mentoring manner that facilitates a sense of safety and belonging.

Guiding Principles

Each school community committed to including parents in the TISP orientation and training process, and to nurturing parent-school partnerships, will accomplish these goals in their own manner, congruent with their context. However, there are a few guiding principles to incorporate to maximize parent engagement and support.

Use Licensed Mental Health Professionals. Imagine what might arise once a parent cohort understands that TISP is more than a school’s approach to learning, but a global trauma-informed movement of adults committed to using advances in science and child development to stop a generational transmission process of unmitigated stress and trauma. Such a network of parents can be self-driven through a peer mentor model whereby parents who have undergone a training or workshop and have participated in parent network groups can then share in facilitation processes. Peer-run volunteer groups are the most powerful community resources inspiring insight, growth, and change. We see this in action everywhere from self-help groups to volunteer organizations.

However your Strategic Planning Team envisions parent participation processes, LMHPs should participate in the strategic planning processes on District and School levels, co-facilitate parent TISP orientation sessions, and lead parent trainings for two reasons. First, the nature of the material requires insight into how to unpack provocative material in a manner that inspires curiosity and hope. It cannot be presented through matter-of-fact information dissemination. And, as already stated, parents deserve the fullness of the message, not just sound bites that may lead to fear and shame. We learn best by encounter, by being both participant and observer, so we need to go slow and steady, as parents will have a personal encounter with this material.

The second reason to use LMHPs as trainers is related to the first. Parents will engage with the material, their own history with unmitigated stress and trauma, and their own adult struggles including questions regarding what they are unknowingly passing along to their children. MHPs are trained to help us hear the truth of our own stories to facilitate greater levels of ownership, leading to compassion for self and others and an openness to change. At a school-sponsored event, there is also the need to provide safety mechanisms in case a participant needs more follow-up care. An MHP will know how to identify these issues and link parents with the appropriate resources.

Orientations can be co-facilitated by LMHPs and school personnel, while parent TISP trainings require LMHP facilitation. After a season of mentoring, many of these processes can be facilitated by peers as well. Once a cohort of parents self-identifies how they might want to continue nurturing their own trauma-informed skills, an MHP can serve as a co-facilitator or an on-call resource as needed, or as the go-to person to run the initial trainings.

Avoid Open Trainings. Once a district commits to orienting parents, it is logical to want to include parents in open school-sponsored TISP trainings. However, this is not advisable for two reasons. First, as a presenter unpacks the neurobiology of unmitigated stress and trauma, and the implications of ACE scores, parents who have had no advanced orientation to ACES or, more significantly, trauma-informed materials, may be overwhelmed and interpret TISP as a response to poor parenting. Sometimes this can be aggravated by how a presenter speaks of parents, but our defenses are usually activated when we hear someone explain how we might not be serving our children well. Without this material being presented in a fuller context with more attention paid to their receptivity and response, including parents could undermine the very goals prompting the invitation. They need a protected space to enter into the content with an attuned facilitator who can mentor them through the material at their own pace.

A second reason to avoid inviting parents to open trainings is that school personnel are also entering a learning process that includes an initial stage of discomfort. Many of us are frustrated that so many students are not able to display age-appropriate skills prerequisite to learning. As we unpack the heart- and brain-crushing blow to a child who is denied access to good-enough attachment, we are angry and, yes, resentful toward parents. Educators need an uncensored space to process these thoughts and emotions, and their own histories and current relationships are placed under the microscope as well.

There are two exceptions to this recommendation. First, many of the educators present in TISP trainings will be parents, and may have K-12 children attending the same districts in which they teach. But the school training environment is designed to attune to their responses. They work in a community of others participating in the same process. Ideally, space is provided for these educators to share how the material is challenging them as both educators and parents.

Another exception is those parents who are already well-known to the school through serving as classroom volunteers or in other roles. They may be familiar enough with trauma-informed literature to be excited about the school’s process and eager to participate. Just be sure to provide these parents with the same type of school support as that offered to school employees.

Crafting a Parent Orientation and Training Plan

Nurturing parent interest in TISP orientation meetings or events is much like building interest among educators. You are likely to have parents who are all in from the start. They are aware of the literature and eager to network with other parents committed to breaking generational patterns, or at least support their child’s school in whatever ways they can. Other parents may be quite unaware of the trauma-informed/ACE revolution, but once they read a short blurb about it and how schools are incorporating this material into their child’s education, they too are all in.

Then there are parents who will know about ACES or have heard about trauma-informed tips for health and well-being, and they want nothing of it! They may display outright avoidance or anger, and claim they lack the time, need, or interest for such nonsense. Other parents may claim interest yet actually wish to avoid all contact with the subject matter.

Our intent is to attune to each parent’s response, honoring their current level of interest, and keep our ears open to offering TISP orientation events in a manner meaningful to each parent. The key principles here are mindfulness of how promotional materials are presented and honoring constraints on parent availability.

Be Mindful of Promotional Materials. Promotional materials include the information you convey to parents about the nature and purpose of TISP, not just the invitation to an orientation meeting or training event. How might you describe TISP in a manner that raises interest but not defensive alarm; piques interest but not fear; and conveys that the school needs to partner with parents, not send parents to therapy or parenting classes?

Honor Parental Constraints. Parental constraints often occur along two themes: resistance to the topic and limitations in scheduling and availability. Resistance to the topic may be related to truly not wanting what is being offered. If it sounds like a parenting class when none was requested, it is unlikely many will want to participate. This is where the District and the LMHP need to be clear about the intent and goals of the activities offered. The rationale is all about including parents in the life of their child’s school, whether simply to enable informed consent, or as preparation to volunteer in the school. And yes, a TISP-informed home does promote the efficacy of TISP. It is similar to only training some teachers that come in contact with a student versus training all teachers; success is much more likely if that student experiences consistency among adult caretakers at school and home.

The District and LMHP need to craft a larger plan designed to build parental interest, and options for parents who want to go deeper into their own TISP training out of curiosity or a desire to volunteer. These two options (an orientation and training) allow parents control over when, how, and why they dig into material that will ultimately invite them to apply TISP concepts to their own life and history, all as precursors to implementing changes in home-based attunement and mentoring parental practices.

Promoting Your Orientation. Once your larger plan is in place, you are likely to begin building interest by letting parents know about your school’s transition to TISP. Parents are likely to positively respond to invitations to a TISP orientation meeting to better understand the changes occurring in their children’s classrooms, perhaps tagged onto student-teacher meeting events, as one of the stops on the circuit of office visits. Such invitations are mindful of how to describe the school’s approach, along with ways to access deeper information if desired. The title of such a program needs to be considered ahead of time, including the wise use of the words “trauma” and “trauma-informed.” The invitation might include elements of the following:

- A statement regarding how our school(s) have learned a great deal regarding the impact of stress on the brain, impacting behavior and learning. This information comes from studies on trauma. This body of knowledge is often called trauma-informed.

- We have incorporated the discoveries from these studies and created learning communities focused on providing a sense of emotional and physical safety, of building community with students, staff, and parents. These are factors that help children focus and learn.

- This orientation session is designed to offer parents the same information we have been providing staff at your child’s school, so you can understand what your child is experiencing at school.

- After this orientation, you might want more information about our new school community approach, how it works, and what staff members are learning and practicing. Or, you might want to serve as a trauma-informed (or whatever descriptor you might choose) class volunteer. If either of these are of interest to you, we will let you know about a parent network designed to provide deeper orientation and training.

- Our staff has found these orientations very informative and thought-provoking, since stress and trauma impact all of us—adults and students alike. So while you are learning about how stress impacts a child’s health and ability to learn, at times it may feel like you are learning about your own brain and recalling your own history as a student. You are not alone! Your child’s teachers are experiencing this same process.

- So, come join us for a one-hour orientation meeting on any one of the following dates. Here, you would offer multiple meetings designed to be most convenient for parents.

In the principles above, you see the concepts of “trauma” and “trauma-informed” being used in context, and descriptors of the program—a community characterized by safety and connection—being used rather than the term signifying the knowledge source informing the program. This is designed to avoid alarming a parent that this is a “mental health treatment” program while also speaking clearly and honestly. A dilemma in many professions is that our shorthand titles are originally designed to speed communication, but the essence of their meaning is soon lost. Judicious use of the word “trauma” invites us to never lose sight of what we are ultimately trying to convey.

The sample above also illustrates informed consent: We are doing this, and only this, and for this reason. Meanwhile, it allows parents to tuck in their memory that more is available, if interested. And, the ultimate informed consent is the acknowledgement that this new program evokes thoughts and feelings. In speaking this truth (one of the elements to helping us all summon good coping resources), it also models two TISP community values: We are all participating in this learning process, and you are not alone. This begins to emphasize collaboration, partnership, and the message that we are all in the same boat in our susceptibility to the impact of generational and unmitigated stress and trauma.

In the above sample, flexible programming honors the time constraints on parents. This may be a District’s biggest challenge, given that the days are gone when most adults had a common work schedule and most families are already stressed by overcommitment to various activities. While a simple orientation might only require an hour of a parent’s time, scheduling parent training will be more difficult. A few ideas might help manage this constraint as it relates to parent trainings:

- Survey your parents and find common times and meeting locations that work for the majority of interested respondents. Plan to offer a variety of trainings to accommodate these variances.

- Offer a small series of three to four meetings, with the option to continue after a break. This allows parents to tolerate the added stress in their schedules for short periods of time.

- After the initial training in TISP, allow the parents to identify ways they might want to network with other parents who have gone through the training for mutual support or friendship.

Parent Orientation and First Training Session Agenda

Your school may choose to offer parents an orientation to their child’s trauma-informed school, using language for “trauma-informed” suitable for your constituents, as highlighted here and in previous chapters. The goal is to enable informed consent to build trust and goodwill, and further develop partnerships with parents who may want to serve as volunteers especially as they become more interested in trauma-informed learning methods. Orientation sessions may be facilitated by school personnel while training sessions are facilitated by LMHPs.

To build trust and interest, parents first need to be informed about the learning methods at their child’s school through a simple one-hour orientation, blurbs in school-parent communications, and other methods. For parents who wish to learn more or are interested in serving as classroom aides, they need access to a TISP training process, a place to understand the methodology behind the school’s emphasis on Connecting, Coaching, and Commencing, and how they can play a significant role in assisting teachers with simple yet effective acts of care expressed through attunement and mentoring. Likewise, they can help classroom methods take hold by practicing some of the techniques used at school and adjusting them for use at home.

The following is intended not as a verbatim script, but as an outline for presenting an orientation to TISP for parents. Put the ideas in your own words to match the context of your students and parents. A TISP orientation session and first training session cover much of the same information; however, the training session includes more direct information about ACES, and is facilitated by a licensed LMHP. The outline below offers a sample progression of ideas for both an orientation and a first training session, due to their similar content.

- An introduction explaining the context inspiring the change in school programming: emerging data gaining the attention of schools around the world, as all of us—not just our district—know that our kids live in a very stressful world, and it has impacted their ability to learn and function in the school environment.

- Unpack with parents what we have learned about stress and learning in clear-cut, concise ways, using visuals or video clips. In a first training session, include space or an activity for parents to share their own observations about the relationship between stress and learning or being motivated.

- In an introductory orientation session, explain that educators (teachers, administrators, all staff) have been overwhelmed by these advances in our understanding of the relationship between stress and development, but truly inspired by little things we can all do to help our students learn and help ourselves manage the impact of stress as well. These sessions can be facilitated by school personnel.

- In a first training session, the LMHP would introduce the work of Felitti and Anda (1998), medical researchers and practitioners who noticed how stressed many adults were, regardless of education, where they lived, or the types of jobs they had. They wondered about the connection between our adult struggles and our childhood stress. By making it personal (our struggles and stress), you illustrate we are all in this boat. By going “generic” (their struggles and stress), you put some distance between these other, unknown adults and the parents present at this moment. Either choice could have wisdom for your group. The key is to think through the messages that might build safety and trust the most with your parents. I (Anna) have found it helpful to let people know that we are all cut from the same cloth, that what I might ask them to unpack and how I might be inviting them to respond holds true for me as well.

- In the first or second session, describe the ACE study: simply, 10 questions designed to see how many types of stressful experiences an adult may have encountered in childhood. And then describe how the ACE researchers learned that persons who experienced stressful events in childhood reported more struggles in adulthood than persons who did not have as many stressful experiences.

- But what we also know is that for many of us, stressful experiences teach us how to be resilient, when we have caring others to help us make sense of those stressful times. We just know more clearly now that stressful events do take a toll on our bodies and brain development.

- And while it is a little uncomfortable realizing that we are impacted by stress in ways we know and don’t know, educators have also learned that the antidote, the protective fix, is simple: When we help students feel loved and cared for, they can start to make sense of the fact that even though life has hard challenges, they matter and they have worth and potential. And when their stressed brains begin to feel safe and calm down, it allows their learning brains to kick into high gear.

- We know this is true for adults too. Even though we face many challenges in life, when we know that others see and care about us, we don’t feel so alone. This helps us access our inner strength and hope, and all the skills we’ve learned over the years, to cope with our hard challenges.

- This is what our teachers are learning—yes, they are going back to school! As they understand the impact of stress on the mind and body and that the best medicine is love and care, they are excited about what this means for their students if we change just a few things at school. Our teachers have always loved and cared for our students, but we are learning new and different ways to provide care that help protect their brains from stress so they can be successful in school.

- And, all of these new discoveries about how the brain works in response to stress are inviting them to make a few changes in their own lives so they are more protected from the impact of adult stress.

- Proceed to give examples of what the school and classrooms are doing to emphasize not just the care of teachers for students, but nurturing care and trust between classmates.

- In a one-hour orientation, invite feedback and questions. Then be sure to offer an avenue for them to learn more or to participate in a TISP training (using your school’s language for the relationship-focused learning community you are creating).

- Be sure to provide the names and contact information for personnel at their children’s school, where they are invited at any time to visit with questions or to observe a school or classroom in action. A member of the school’s Strategic Planning Team is often a good contact source.

- In a first training session, invite feedback and questions; ask what might be inspiring or disconcerting. What is it like hearing that your teachers are learning about stress and the brain? What is inspiring them to learn about stress and the brain?

- If time allows, or in the second meeting, invite them to take the ACE. There are methods to do this rather quickly and simply, so a parent can keep their own scores private. Enough time must remain so you can unpack scores. If not, then let your parents know that they can take the survey the next time you meet if anyone is interested.

- To unpack the scores, be mindful that you need a parent’s trust before you overwhelm them with ACE score correlation data. So, until greater trust is built, simply explain that high scores are not uncommon, and health and relationship struggles are common regardless of how many childhood stressors we experienced. We just know that those of us who have lots of adult challenges also had some fairly tough stressors when we were kids.

- Here is where you introduce the neurobiology of stress that would be unpacked in greater detail in a second session. Parents need to hear some of the most validating news: We can’t just simply tell ourselves to feel happy, or to not be angry, or to never make bad choices, or to know when to trust and when not to trust. Our physical bodies changed due to stress, and we carry all sorts of messages in our bodies that impact how we think and feel, what we want and need, how we perceive safety and danger. Explain how next time you meet, you will unpack some of these physiological challenges and how we are learning the key to taming some of these stress side effects.

- With each mini-lesson into the nature of unmitigated stress and trauma, remember to connect it to how children display these concepts in the classroom.

Parent Training Curriculum Development

The content of a parent training in TISP-based schools is not about the TISP competencies of the educator; it focuses on the science underlying trauma-informed data regarding what undermines and promotes healthy development, followed by practical steps to strengthen attachment skills at home. Each LMHP familiar with trauma-informed practices, family therapy, and parent education skill basics can develop a suitable curriculum. The following are key topics to build into your curriculum.

NEAR Agenda Model. A great resource that offers a glimpse into the content domains of a short TISP training program is the NEAR (Neurobiology-Epigenetics-ACES-Resources) model, a trauma-informed parent education curriculum used to orient home health care workers in trauma-informed practice (Region X ACES Planning Team, 2016). The model is based on two guiding values: Families have a right to know what research has verified regarding the ingredients for healthy development; and families have a right to know the devastating consequences of unmitigated stress and trauma so they can prevent harm to themselves and their children. The acronym is designed to simplify the parent education process, a deep-enough look at research findings without overwhelming parents or monopolizing too much of their time. The program also includes a simple method for sharing the information with parents focusing on Asking, Listening, and Accepting. A a quote from Vincent Felitti expresses a discovery many of us make as we learn the power of active listening: “Slowly, I have come to see that Asking, and Listening, and Accepting are a profound form of Doing” (p. 17).

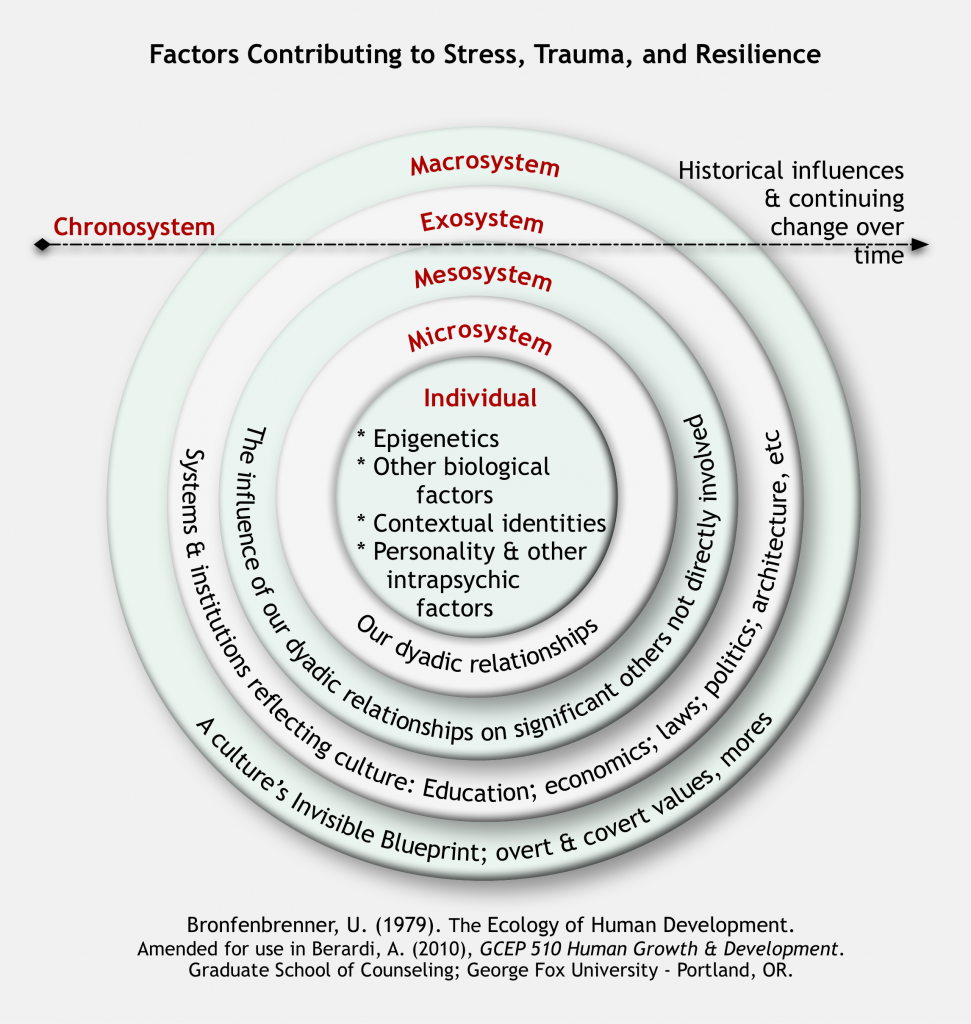

Remember the Broader Picture. The above blueprint is a useful guideline even though LMHP parent facilitators need to be aware of developing additional content pieces as needed. Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) model of factors shaping personal health and wellbeing is helpful. (see Figure 10.1). At this point in our history, we have many open ears responding to the pervasiveness of dysregulated Microsystem relationships, the picture that is emerging through Adverse Childhood Experiences data. Advances in neurobiology add to the chorus by illuminating not just psychological implications, but biological correlates, all comprising the impact on the individual. But systems therapists and social science theorists remind us to pull the lens out to see broader issues driving the pervasiveness of dysregulated behavior. And lest we think ACES are the only source of an adult or child’s trauma, we know that this is not the full story. We saw this juxtaposition in Section I in the stories of Charlotte and Ben.

Most notable is the role of contextual factors influencing risk and resilience. This includes the acknowledgment of historical legacies, cultural attitudes and practices, and social systems reflecting what is privileged or marginalized around personal identity traits such as race, ethnicity, religion, gender identity, gender roles, national identity status, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, appearance, age, and ability. What makes these personal identifying traits a risk factor is directly related to Chronosystem legacies, Macrosystem blueprints, and Exosystem structures shaping public attitudes and behaviors. Most notable is the role of contextual factors influencing risk and resilience. This includes the acknowledgment of historical legacies, cultural attitudes and practices, and social systems reflecting what is privileged or marginalized around personal identity traits such as race, ethnicity, religion, gender identity, gender roles, national identity status, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, appearance, age, and ability. What makes these personal identifying traits a risk factor is directly related to Chronosystem legacies, Macrosystem blueprints, and Exosystem structures shaping public attitudes and behaviors. These issues are reflected in the ways we organize ourselves as a society; we see covert and overt values, attitudes, and beliefs expressed in our public institutions, our economic system, politics, even our architecture. These Exosystem factors not only reflect the invisible blueprint (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), but keep systems of power, a sense of what is good and desired, firmly in place, no matter their utility or influence over those conscripted to play a role or not even acknowledged as participants in the process.

When we struggle to feel safe, included, or worthy, we are taught first to ask, “What am I doing wrong?” or “How has another person done me wrong?” We are not often guided to look around at how we might be in a toxic stew chipping away at everyone’s sense of self. This is what an ecosystemic view does: It helps us put words to a larger issue at play. By putting words to the crazy-making dynamics we experience or see on a daily basis, issues or events that others might be oblivious to, it provides the type of attunement we need to feel safe and anchored so we can move on to proactively respond in health-promoting ways. By putting words to the crazy-making dynamics we experience or see on a daily basis, issues or events that others might be oblivious to, it provides the type of attunement we need to feel safe and anchored so we can move on to proactively respond in health-promoting ways. Many of our students’ parents suffer directly or indirectly due to Chrono-, Macro-, and Exosystem dynamics that do influence social-emotional functioning. In fact, researchers from a variety of disciplines surmise that Macrosystem factors have the single-most influence over our identity formation process (Alexander, 2012; Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler, & Tipton, 2007; Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Coates, 2015; DiAngelo, 2018; Woodley, 2019). From an attachment perspective, this makes perfect sense, since these invisible attitudes and values creep into our psyche in a pervasive yet subtle way from the moment we are born. An mental health professional needs to see this broader picture of factors influencing our encounters with unmitigated stress and trauma in order to attune to parents suffering not so much from ACES, but a larger toxic process.

A facilitator will also want to identify resilience traits often born in the face of stress and adversity. A significant part of the curriculum should also include basic attunement skills parents are invited to strengthen to mirror the strategies used at school.

Unpacking ACES—Should We or Should We Not? Whether you adopt the NEAR model as an outline or create your own, inevitably a significant aid for people to fully grasp the impact of unmitigated stress and trauma on biopsychosocial health throughout the lifespan is a review of the ACE survey. The mental health profession is built on the understanding that most families we work with are manifesting the impact of both generational trauma and here-and-now (adverse) experiences that are causing physical, emotional, and social harm to all family members, especially children. And, as detailed above, we know these dysregulated relational behaviors are influenced by larger social forces.

What is new is discovering the percentage of families experiencing profound disruptions to providing safe and stable attachment bases for children, the general public’s increased awareness of this phenomenon, data verifying its costs to individuals and communities, and the ethical obligation we face to share this information with all adults. In addition, ACE data is merging with advances in epigenetics—the field of science that explores biophysical changes that occur idue to unmitigated stress and trauma and are passed on to future generations (DeSocio, 2018; Ptak & Petronis, 2010). We are now gaining rapid and startling knowledge into how the damaging side effects of trauma attach to our genes, basically programming how our genes will act. These alterations are often passed down. Your students might have low ACE scores, but still be suffering from the side effects of inherited trauma in a compromised immune system, physical struggles, or neurological difficulties ranging from cognitive functioning to a propensity for chronic anxiety, depression, or other mental health struggles. We truly do carry the memories of our ancestors in our bones. (See the Resources for Further Reading at the end of this chapter for more information.)

This complexity is most salient as we are appalled at the relational distress many of our students experience at home. It can be difficult to summon respect and empathy, even though many of us have struggled in our family relationships as well. In this chapter, we are giving you a glimpse into the mindset of systems therapists who see these struggling families with great empathy even as they too are feeling the urgency on behalf of children.

What the ACE data has inspired is a renewed effort to intervene in families. Health care providers of varying professions are now being overtly asked to talk with families about ACES. Even trauma-informed educators (us included!) are being asked to loop parents in on ACE-inspired changes to their child’s school approach. Here, we invite all school personnel to proceed with caution.

When someone tells us that the way we are sailing along in life is hurtful, in fact inspiring lifelong pain, a logical reaction is to feel shame. We might respond to it in a variety of ways that mask the reaction, but it is as if some spotlight now shines on us and all of our flaws and inadequacies are seen, including the toxic effect we’ve had on those we love most. It’s overwhelming. But just as educators are in the business of coaching students to learn from mistakes, to not implode with shame each time they are corrected or redirected, a similar process unfolds with each of us when we are confronted with aspects of our relational or personal functioning that need to change for our own health and the health of our children.

As your TISP-transitioning school seeks to contract with licensed mental health providers to sponsor parent training in TISP, interview these providers and ask how they will share the historical origins inspiring TISP, and how they would describe to parents the correlation of ACES with a student’s academic functioning. Listen for an awareness of truth-telling but within the whole truth, of inclusive language rather than “us non-ACE-producing adults” versus “those high-ACE-producing parents.”

As your school or district decides to gently ease into building interest among parents, we recommend that in a one-hour orientation to your TISP schools, unpacking ACES is not appropriate. More time needs to be given to that study in particular, and in one hour you want to present their child’s emerging school environment as a welcoming place for their child and them as the parent. However, it is very appropriate to explain the findings of ACE in a non-threatening manner.

Above, we identified a process for unpacking the ACE survey and the correlation between scores and lifespan struggles that would comprise one of the first TISP training sessions for parents who want to go deeper. Most of the information covered in that first training session would be a repeat of the one-hour parent orientation session. And again, our main goal is to invite parents into the topic, not overwhelm them with fear and shame, or provide provocative information with no opportunity to ask questions or process their reactions.

Nurturing Parental Trust. The last principle to incorporate into our work with parents is the idea of holding gently the vulnerabilities and hopes of parents when they need our help with their children. We’d like to share a few thoughts from one of Anna’s students. Jennifer chose to become a systems-based therapist due to her own experience as an adoptive parent. She gravitated toward attachment-based family therapy intervention models, and then decided to complete a trauma-informed research project exploring a hunch. She is intimately acquainted with the exhaustion of parenting and the microscope that she is placed under each time she works with the education, medical, and mental health systems on behalf of her family. She can easily discern if they assume she is somehow causing the problem or contributing to making it worse. Meanwhile, in her clinical practice, Jennifer works with many parents who have experienced their own unmitigated stress and trauma, and are also parenting high-needs children with complex struggles. Her hunch was, if we help parents nurture their own connections, their own attachment relationships, might that result in an internal sense of safety, inspiring hope and greater coping skills? After all, there is no magic bullet out there that is going to make life less stressful in this moment. Might we increase resilience if we help parents spend less time trying to figure out how to do it faster or better, and first nurture their own need to feel safe, loved, and valued?

Sound familiar? This is the same approach we are taking with our students: nurturing connection and then trusting we will have a firmer foundation to tolerate the day’s challenges and find the resources to cope.

In the course of Jennifer’s research, we’d often discuss what various professionals can do to ease the pressure, to lessen the shame and blame, whether real or imagined, that parents and guardians often feel when they are caring for children with complex struggles. Her advice is simple and practical.

Four Tips for Communicating with a Student’s Parent or Guardian

- Parents, regardless of their role in their child’s behavior, are coming to you, whether you are their teacher, administrator, or school counselor, feeling judged and ashamed. They may appear to be defensive, blaming, or simply exhausted. But understanding their underlying shame and finding empathy for them will go a long way in creating a respectful and collaborative relationship.

- Parents are the experts on their child— even when they may not feel or appear that way to others. Be curious about what does and does not work at home. Many parents have excellent ideas, but may not know how to explain them in the best way.

- Listen first, and reflect what you are hearing rather than assuming you know how they feel. When you let parents know you hear them, they will be much more likely to join the team in a more meaningful way. Many parents may not have an emotional vocabulary, especially in regard to their feelings toward parenting a child with high needs. By reflecting what you hear, you are giving them a chance to understand themselves as well.

- Many teachers already highlight strengths of the student in meetings with parents, but it is important that you do so in a way that helps the parent understand you really are trying to get to know their child in a meaningful way. Letting parents know you really see their child, good and bad, will help them respect you more.

—Jennifer Pond, Marriage and Family Therapist Intern

Parents as TISP Partners: Final Thoughts

Teachers need more adults in the classroom. Gone are the days when children were programmed to sit in tidy neat rows of desks, folding their hands when not at work, and sitting straight up quietly at attention. My (Anna’s) primary school class pictures remind me of how large our classes were—40, 50, or more students—and each of us knew that strict consequences awaited if we didn’t keep our hands to ourselves, spoke out of turn, or didn’t complete our nightly homework. Those expectations worked to create quiet, compliant students. We still hear pockets of community members who think we should return to those swift and clear law-and-order days. But that orderly-looking classroom came at a great cost to many of its students, pairing learning with fear and shame. Its side effects went hidden for many of us. Luckily, enough has changed in our culture that those types of practices are no longer tolerated by educators, students, and their families.

Including parents in TISP orientation and training processes seems like a daunting task; we can’t imagine some of our most vulnerable parents ever choosing to participate. TISP trusts that deeper, lifelong learning, or tackling an emotionally challenging subject, is of interest to most of us when it occurs within an environment of Connecting and Coaching. And to provide this type of attention to each student, most often we need more than one adult in the classroom. Teaching is exhausting work, and it is impossible when you have a dozen or more students needing you to provide that sense of attunement so crucial to their learning process. We need parent partners not just to help with tasks, but to help each student feel connected, seen, and valued.

Orienting parents to TISP is also a strengths-based strategy for helping parents understand the health crisis schools are responding to by embracing TISP. As parents learn more about the generational legacy of unmitigated stress and trauma, their own sense of hope is activated by knowing there is a way to be proactive and involved with all of us trying to do the same. We are assuming that changes will happen not only at home, but in community hope and cohesion as well. To help parents understand the full nature of the problem, they deserve to see a wide-angle view of how it impacts all of us and is bigger than any one person or family. In response, they also deserve to see the beauty in the microscopic, closeup view found in the healing influence of attuned relationship. Parent involvement in classrooms is the solution in action. To help parents understand the full nature of the problem, they deserve to see a wide-angle view of how it impacts all of us and is bigger than any one person or family. In response, they also deserve to see the beauty in the microscopic, closeup view found in the healing influence of attuned relationship. Parent involvement in classrooms is the solution in action.

Exercises

Chapter 10: Exercise 1

Create TISP Orientation Activities

Context

Imagine you are part of a district committed to building parent/guardian support and interest in your school’s trauma-informed culture and practices. You have partnered with a trauma-informed licensed mental health practitioner trained in systems-based family services, and you have the broader commitment of your education system to nurture parental buy-in.

The first phase is sharing information about your trauma-informed school approach and nurturing further interest. This is the orientation phase; it is not one event, but a series of communications over time. Three of the most common forms of school-parent communication are e-newsletters or announcements on your school’s website; paper announcements sent home with students; and parent-teacher open house meetings each term, which may span a few days during a given term to accommodate parent schedules.

Instructions

- It is not always wise to call a school’s approach “trauma-informed” or “trauma-sensitive” due to the confusing message it may convey to those unfamiliar with the literature. Research or professional terms do not always sit well with recipients of, in this case, a trauma-informed approach. What might you want to call your trauma-informed district, school, or classroom? This would become the descriptor used in your parent communications.

- Construct the narrative for each of the following communication items:

- General TISP Introduction: E-newsletter blurb or take-home note: The narrative announcing and describing the school or classroom TI approach.

- TISP Orientation Meeting: Construct an announcement or e-brochure promoting a short orientation meeting for parents that will describe in greater detail your school’s trauma-informed culture.

- Create an agenda for a one-hour parent orientation meeting.

- Identify roughly how much time might be spent on each element.

- Assemble the content for each element as is congruent with your class assignments or the readiness of your current school or district to implement this activity.

- Share your responses to this exercise with others working with you. How might their examples strengthen your own ideas?

Chapter 10: Exercise 2

Develop a TISP Parent Training Program

Context

Imagine that you have a small group of parents interested in knowing more about your school’s trauma-informed programming. Some want to become or are already working as classroom aides, and others are just curious. For this scenario, let’s imagine the group can easily find a common meeting time.

As in the above scenario, imagine you are working with a trauma-informed systems therapist. If you are an educator, having a general idea of the content to be covered is good practice seeing in action with adults what you are putting into practice with students. It also helps you be sure that the MHP covers material you need them to address, as this is the birth of an idea you hope can spread to other parents, effecting change in the home.

Also imagine that you are calling it a “training” because it will be in service to parents who want to work as classroom aides, and for the curious who want to go through some of the same materials (concepts) as their child’s teacher. This avoids creating or promoting it as a parenting training or group therapy process, both of which are presumptuous, implying that the parents are the problem. With this caution in mind, what other terms or descriptors might you use, if “training” sounds too difficult or formal? Once TISP parent involvement takes hold, the parents themselves may wish to rename the process to fit their vision of how to grow a TISP parent network.

If you are an MHP, imagine that you are co-constructing your training agenda with educators serving the students of the parents in your training. As more parents participate in the training, imagine that these parents become part of the planning team as well.

Instructions

- Create a general topic list while deciding how many sessions an introductory TISP training might take. Adjust your topic list or depth of each topic to accommodate parent time demands, giving plenty of space for parent interaction in each session.

- Identify a theme for each meeting, arranging the themes in a developmental, scaffolded sequence that makes conceptual sense and is mindful of the process parents may go through as they digest the material.

- Identify the agenda for each themed meeting.

- Identify tools or methods of engagement you might use to keep the sessions interactive and training-focused rather than a group therapy or parent training workshop in disguise.

- What local physicians or researchers might you bring in to describe epigenetics or ACE data? How might you screen their approaches to be sure they do not lecture the participants to change, but share scientific data in a approachable way that is informative?

- What school staff, from a variety of roles, might you invite to your meetings to share their learning process and the “aha” moments they have observed with students?

- As more parents complete TISP training, how might you include parents as co-facilitators?

- What visuals (videos, pictures, etc.) might you want to track down to illustrate various concepts?

- Once the shell of your program is created, share your ideas with others working through this material to generate more ideas.

Resources for Further Reading

- ACES Infographics.

- ACES Connection Resources Center.

- ACES: ACE Study video. Three-minute trailer by Academy on Violence and Abuse.

- ACES: “Video: Toxic Stress Derails Healthy Development” by Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University.

- ACES: “Video: How Childhood Trauma Affects Health Across a Lifetime,” TED Talk by Dr. Nadine Burke Harris.

- NEAR is an acronym to denote the roles neuroscience, epigenetics, ACES, and resilience play in our vulnerabilities to unmitigated stress and trauma. This website offers resources to home health care workers to discuss ACES with families.

- Epigenetics: “Grandma’s Experiences Leave Epigenetic Mark on Our Genes,” Discover article by Dan Hurley.

- Epigenetics: “Holding Infants—or Not—Leaves Traces on Their Genes,” University of British Columbia Faculty of Medicine.

- Epigenetics: https://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/epigenetics/rats/.

- Epigenetics: https://bigthink.com/videos/epigenetics-explained.

- Epigenetics: WhatIsEpigenetics.com. News site covering epigenetics.

- Epigenetics: “Epigenetics” by Learn.Genetics. Explainers and backgrounders about epigenetics.

- Neurodevelopment: Brain Story Certification Course by Alberta Family Wellness Initiative.

- Neurodevelopment: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/.

- Neurodevelopment: “Brains: Journey to Resilience” by The Palix Foundation.

- Neurodevelopment: “First Impressions: Exposure to Violence and a Child’s Developing Brain“.