11

“The secret of change is to focus all of your energy, not on fighting the old, but on building the new.” —Socrates

Desired Outcomes

This chapter and the accompanying recommended readings and activities are designed to further develop educator trauma-informed competencies as demonstrated by:

- Understanding the importance of revising teacher preparation and educator and administrative credentialing standards in response to today’s student challenges

- Envisioning how current InTASC standards can incorporate the Trauma-Informed School Practices Tri-Phasic Model dispositions into their structure

- Advocating for change within academic institutions, legislative bodies, and professional accrediting organizations congruent with the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required for effective trauma-informed school practice

Key Concepts

This chapter contains a proposed revision to Interstate Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (InTASC) standards. Our goal is to initiate a conversation and inspire educators in all aspects of professional practice to advocate for systemic change in the way educators are prepared for practice. Key concepts detailed include the following:

- The role of InTASC in teacher and administrator credentialing processes

- The rationale for proposing a refresh of InTASC according to the Trauma-Informed School Practices Tri-Phasic Model as detailed in Chapter 6

- The role of advocacy on behalf of the education profession and the needs of students

Chapter Overview

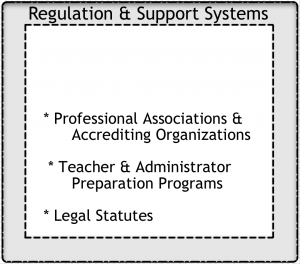

The final section of this text identifies additional systemic factors requiring change in order for educators to serve the needs of today’s students. This chapter specifically addresses the need to revise and update educator preparation and practice standards. This system element comprises three domains: (a) practice law as detailed in national and state legislation regarding educator competencies, student outcomes, and other issues related to education systems; (b) educator professional associations, including accreditation organizations; and (c) higher education programs training educators, including preservice teachers, administrators, and those seeking specialty credentials.

A trauma-informed educational approach represents the introduction of a multidisciplinary body of knowledge, skills, and dispositions not traditionally featured in current teacher and administrative credentialing programs. This creates a problematic domino effect, in that recently graduated educators are ill-equipped to understand and respond to the learning needs of students, and trauma-informed schools are unable to hire qualified staff. To solve this problem, educators, mental health professionals, and public school advocates within legislatures, professional organizations, and higher education need to work together to encourage the profession to incorporate TISP competencies.

In Chapter 6, we outlined the Trauma-Informed School Practices Tri-Phasic Model specifically detailing trauma-informed content domains and the knowledge, skills, and dispositions needed at all phases of trauma-informed educator practice. This document is suitable for use by higher education teacher and administrator preparation programs seeking to hire faculty trained to implement trauma-informed coursework into their existing curriculums. The document also serves as a guide for K-12 educational settings implementing trauma-informed practices.

In this chapter, to begin a conversation regarding how to address needed changes within accrediting associations, we explore what a revised InTASC standards document might look like. This proposed document, along with the TISP Tri-Phasic Model, invites you to advocate for change on all levels of teacher and administrator standards of practice, from professional accreditation standards, to practice law, to educational training programs.

Refreshing InTASC Standards: The Pre-Contemplation Stage

Recently, I (Brenda) was asked to speak to a group of preservice teachers in their second semester of student teaching. During introductions, two students stated they worked in “trauma-informed schools” and one said she had a cooperating teacher who was a “trauma-informed” teacher. I was curious to learn more. How did they know they were working in a trauma-informed school? How did they or their school define trauma-informed? What made this teacher trauma-informed? How does one know when they have developed trauma-informed competencies?

Accredited teacher preparation programs follow specific standards for what teachers must know and be able to do; many of these programs have used the Interstate Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (InTASC) standards as their guide. The InTASC standards include performances, essential knowledge, and critical dispositions teachers need in order to be successful in the profession (Council of Chief Operating State School Officers Interstate Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium, 2013). These standards were originally created in 1992 for beginning teachers. In 2010, they were updated to include professional practice standards for different stages of the educator’s development (Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010, p. 1).

In Table 11.1, we list the current standards, followed by our recommended trauma-informed dispositions. For your convenience, the trauma-informed educator dispositions from the TISP Tri-Phasic Model (Chapter 6) are listed in Appendix D.

Table 11:1: InTASC Model Core Teaching Standards with Trauma-Informed School Practices Dispositions

Standard 1: Learner Development

The teacher understands how learners grow and develop, recognizing that patterns of learning and development vary individually within and across the cognitive, linguistic, social, emotional, and physical areas, and designs and implements developmentally appropriate and challenging learning experiences.

Performances

1(a) The teacher regularly assesses individual and group performance in order to design and modify instruction to meet learners’ needs in each area of development (cognitive, linguistic, social, emotional, and physical) and scaffolds the next level of development.

1(b) The teacher creates developmentally appropriate instruction that takes into account individual learners’ strengths, interests, and needs and that enables each learner to advance and accelerate his/her learning.

1(c) The teacher collaborates with families, communities, colleagues, and other professionals to promote learner growth and development.

Essential Knowledge

1(d) The teacher understands how learning occurs—how learners construct knowledge, acquire skills, and develop disciplined thinking processes—and knows how to use instructional strategies that promote student learning.

1(e) The teacher understands that each learner’s cognitive, linguistic, social, emotional, and physical development influences learning and knows how to make instructional decisions that build on learners’ strengths and needs.

1(f) The teacher identifies readiness for learning, and understands how development in any one area may affect performance in others.

1(g) The teacher understands the role of language and culture in learning and knows how to modify instruction to be relevant, accessible, and challenging.

Critical Dispositions

1(h) The teacher respects learners’ differing strengths and needs and is committed to using this information to further each learner’s development.

1(i) The teacher is committed to using learners’ strengths as a basis for growth, and their misconceptions as opportunities for learning.

1(j) The teacher takes responsibility for promoting learners’ growth and development.

1(k) The teacher values the input and contributions of families, colleagues, and other professionals in understanding and supporting each learner’s development.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 6: Trauma-informed educators understand the primacy of attachment theory, and its emphasis on attunement, to the neural development of both students and adults throughout the lifespan.

Disposition 9: Trauma-informed educators understand the primacy of attachment theory, and its emphasis on mentoring, to the neural development of both students and adults throughout the lifespan.

Disposition 10: Trauma-informed educators understand that student behavior, in part, is often a reflection of unintegrated neural networks due to past and/or current unmitigated stress and trauma, and require the student to first establish a sense of safety and stability prior to commencing with here-and-now developmental expectations.

Disposition 11: Trauma-informed educators understand that persons all along the lifespan are influenced by past experiences shaping perceptions and emotional responses. It is a lifelong task to understand this connection while learning to self-regulate in the face of intense emotional responses to current events.

Disposition 12: Trauma-informed educators are aware that students process unmitigated stress and trauma in both direct and indirect ways as they engage in all aspects of the trauma-informed educational environment, and are able to offer an attuned and mentoring response.

Disposition 16: Trauma-informed educators understand the nature of a student’s academic and social-emotional functioning in the classroom, and how best to meet the individual needs of each student, whether in a traditional classroom or with additional assistance.

Standard 2: Learning Differences

The teacher uses understanding of individual differences and diverse cultures and communities to ensure inclusive learning environments that enable each learner to meet high standards.

Performances

2(a) The teacher designs, adapts, and delivers instruction to address each student’s diverse learning strengths and needs and creates opportunities for students to demonstrate their learning in different ways.

2(b) The teacher makes appropriate and timely provisions (e.g., pacing for individual rates of growth, task demands, communication, assessment, and response modes) for individual students with particular learning differences or needs.

2(c) The teacher designs instruction to build on learners’ prior knowledge and experiences, allowing learners to accelerate as they demonstrate their understandings.

2(d) The teacher brings multiple perspectives to the discussion of content, including attention to learners’ personal, family, and community experiences and cultural norms.

2(e) The teacher incorporates tools of language development into planning and instruction, including strategies for making content accessible to English language learners and for evaluating and supporting their development of English proficiency.

2(f) The teacher accesses resources, supports, and specialized assistance and services to meet particular learning differences or needs.

Essential Knowledge

2(g) The teacher understands and identifies differences in approaches to learning and performance and knows how to design instruction that uses each learner’s strengths to promote growth.

2(h) The teacher understands students with exceptional needs, including those associated with disabilities and giftedness, and knows how to use strategies and resources to address these needs.

2(i) The teacher knows about second language acquisition processes and knows how to incorporate instructional strategies and resources to support language acquisition.

2(j) The teacher understands that learners bring assets for learning based on their individual experiences, abilities, talents, prior learning, and peer and social group interactions, as well as language, culture, family, and community values.

2(k) The teacher knows how to access information about the values of diverse cultures and communities and how to incorporate learners’ experiences, cultures, and community resources into instruction.

Critical Dispositions

2(l) The teacher believes that all learners can achieve at high levels and persists in helping each learner reach his/her full potential.

2(m) The teacher respects learners as individuals with differing personal and family backgrounds and various skills, abilities, perspectives, talents, and interests.

2(n) The teacher makes learners feel valued and helps them learn to value each other.

2(o) The teacher values diverse languages and dialects and seeks to integrate them into his/her instructional practice to engage students in learning.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 1: Trauma-informed educators create environments that promote the neural integration of their members (students and educators) in order to maximize students’ academic and social success at each developmental stage.

Disposition 2: Trauma-informed educators commit to learning the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required to implement trauma-informed practices according to their role and context in order to promote safe and effective learning communities.

Disposition 3: Trauma-informed educators are committed to embedding trauma-informed rituals and practices within the daily, weekly, and seasonal routines of a school and classroom providing a sense of repetition that deepens internal safety and stabilization. Repetition also emphasizes that basic TISP building blocks are continual and constant, not merely a phase that is completed in order to move to the next phase.

Disposition 4: Trauma-informed educators are aware of socio-cultural factors that increase student risk or resilience, and are committed to creating an educational environment that is welcoming, safe, and inclusive of all persons.

Disposition 5: Trauma-informed educators are committed to a consistent ethic of care whereby the relational values offered to students are extended to self and one another.

Disposition 10: Trauma-informed educators understand that student behavior, in part, is often a reflection of unintegrated neural networks due to past and/or current unmitigated stress and trauma, and require the student to first establish a sense of safety and stability prior to commencing with here-and-now developmental expectations.

Disposition 11: Trauma-informed educators understand that persons all along the lifespan are influenced by past experiences shaping perceptions and emotional responses. It is a lifelong task to understand this connection while learning to self-regulate in the face of intense emotional responses to current events.

Disposition 12: Trauma-informed educators are aware that students process unmitigated stress and trauma in both direct and indirect ways as they engage in all aspects of the trauma-informed educational environment, and are able to offer an attuned and mentoring response.

Disposition 13: Trauma-informed educators are skilled in attuning to grief and mourning responses that often accompany academic engagement as neural networks integrate, which allow for deeper connection to memory and its meaning to occur.

Disposition 15: Trauma-informed educators understand how to weave Connecting and Coaching practices into academic lesson plans, as the learning process, both the process of learning and the content to master, is also crucial to the integration of neural networks impacted by unmitigated stress and trauma.

Disposition 16: Trauma-informed educators understand the nature of a student’s academic and social-emotional functioning in the classroom, and how best to meet the individual needs of each student, whether in a traditional classroom or with additional assistance.

Disposition 17: Trauma-informed educators advocate on local, state, and national levels for greater understanding of the neurobiological impacts on a student when either (a) the student cannot self-regulate or (b) the student is repeatedly exposed to peers unable to self-regulate, leading to frequent episodes of classroom disruption. This constant state of dysregulation and exposure to peers in such states cause more stress and trauma for all students.

Standard 3: Learning Environments

The teacher works with others to create environments that support individual and collaborative learning, and that encourage positive social interaction, active engagement in learning, and self-motivation.

Performances

3(a) The teacher collaborates with learners, families, and colleagues to build a safe, positive learning climate of openness, mutual respect, support, and inquiry.

3(b) The teacher develops learning experiences that engage learners in collaborative and self-directed learning and that extend learner interaction with ideas and people locally and globally.

3(c) The teacher collaborates with learners and colleagues to develop shared values and expectations for respectful interactions, rigorous academic discussions, and individual and group responsibility for quality work.

3(d) The teacher manages the learning environment to actively and equitably engage learners by organizing, allocating, and coordinating the resources of time, space, and learners’ attention.

3(e) The teacher uses a variety of methods to engage learners in evaluating the learning environment and collaborates with learners to make appropriate adjustments.

3(f) The teacher communicates verbally and nonverbally in ways that demonstrate respect for and responsiveness to the cultural backgrounds and differing perspectives learners bring to the learning environment.

3(g) The teacher promotes responsible learner use of interactive technologies to extend the possibilities for learning locally and globally.

3(h) The teacher intentionally builds learner capacity to collaborate in face-to-face and virtual environments through applying effective interpersonal communication skills.

Essential Knowledge

3(i) The teacher understands the relationship between motivation and engagement and knows how to design learning experiences using strategies that build learner self-direction and ownership of learning.

3(j) The teacher knows how to help learners work productively and cooperatively with each other to achieve learning goals.

3(k) The teacher knows how to collaborate with learners to establish and monitor elements of a safe and productive learning environment including norms, expectations, routines, and organizational structures.

3(l) The teacher understands how learner diversity can affect communication and knows how to communicate effectively in differing environments.

3(m) The teacher knows how to use technologies and how to guide learners to apply them in appropriate, safe, and effective ways.

Critical Dispositions

3(n) The teacher is committed to working with learners, colleagues, families, and communities to establish positive and supportive learning environments.

3(o) The teacher values the role of learners in promoting each other’s learning and recognizes the importance of peer relationships in establishing a climate of learning.

3(p) The teacher is committed to supporting learners as they participate in decision-making, engage in exploration and invention, work collaboratively and independently, and engage in purposeful learning.

3(q) The teacher seeks to foster respectful communication among all members of the learning community.

3(r) The teacher is a thoughtful and responsive listener and observer.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 1: Trauma-informed educators create environments that promote the neural integration of their members (students and educators) in order to maximize students’ academic and social success at each developmental stage.

Disposition 2: Trauma-informed educators commit to learning the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required to implement trauma-informed practices according to their role and context in order to promote safe and effective learning communities.

Disposition 3: Trauma-informed educators are committed to embedding trauma-informed rituals and practices within the daily, weekly, and seasonal routines of a school and classroom providing a sense of repetition that deepens internal safety and stabilization. Repetition also emphasizes that basic TISP building blocks are continual and constant, not merely a phase that is completed in order to move to the next phase.

Disposition 4: Trauma-informed educators are aware of socio-cultural factors that increase student risk or resilience, and are committed to creating an educational environment that is welcoming, safe, and inclusive of all persons.

Disposition 5: Trauma-informed educators are committed to a consistent ethic of care whereby the relational values offered to students are extended to self and one another

Disposition 6: Trauma-informed educators understand the primacy of attachment theory, and its emphasis on attunement, to the neural development of both students and adults throughout the lifespan.

Disposition 10: Trauma-informed educators understand that student behavior, in part, is often a reflection of unintegrated neural networks due to past and/or current unmitigated stress and trauma, and require the student to first establish a sense of safety and stability prior to commencing with here-and-now developmental expectations.

Disposition 12: Trauma-informed educators are aware that students process unmitigated stress and trauma in both direct and indirect ways as they engage in all aspects of the trauma-informed educational environment, and are able to offer an attuned and mentoring response.

Disposition 13: Trauma-informed educators are skilled in attuning to grief and mourning responses that often accompany academic engagement as neural networks integrate, which allow for deeper connection to memory and its meaning to occur.

Disposition 15: Trauma-informed educators understand how to weave Connecting and Coaching practices into academic lesson plans, as the learning process, both the process of learning and the content to master, is also crucial to the integration of neural networks impacted by unmitigated stress and trauma.

Disposition 16: Trauma-informed educators understand the nature of a student’s academic and social-emotional functioning in the classroom, and how best to meet the individual needs of each student, whether in a traditional classroom or with additional assistance.

Disposition 17: Trauma-informed educators advocate on local, state, and national levels for greater understanding of the neurobiological impacts on a student when either (a) the student cannot self-regulate or (b) the student is repeatedly exposed to peers unable to self-regulate leading to frequent episodes of classroom disruption. This constant state of dysregulation and exposure to peers in such states cause more stress and trauma for all students.

Standard 4: Content Knowledge

The teacher understands the central concepts, tools of inquiry, and structures of the discipline(s) he or she teaches and creates learning experiences that make these aspects of the discipline accessible and meaningful for learners to assure mastery of the content.

Performances

4(a) The teacher effectively uses multiple representations and explanations that capture key ideas in the discipline, guide learners through learning progressions, and promote each learner’s achievement of content standards.

4(b) The teacher engages students in learning experiences in the discipline(s) that encourage learners to understand, question, and analyze ideas from diverse perspectives so that they master the content.

4(c) The teacher engages learners in applying methods of inquiry and standards of evidence used in the discipline.

4(d) The teacher stimulates learner reflection on prior content knowledge, links new concepts to familiar concepts, and makes connections to learners’ experiences.

4(e) The teacher recognizes learner misconceptions in a discipline that interfere with learning, and creates experiences to build accurate conceptual understanding.

4(f) The teacher evaluates and modifies instructional resources and curriculum materials for their comprehensiveness, accuracy for representing particular concepts in the discipline, and appropriateness for his/her learners.

4(g) The teacher uses supplementary resources and technologies effectively to ensure accessibility and relevance for all learners.

4(h) The teacher creates opportunities for students to learn, practice, and master academic language in their content.

4(i) The teacher accesses school and/or district-based resources to evaluate the learner’s content knowledge in their primary language.

Essential Knowledge

4(j) The teacher understands major concepts, assumptions, debates, processes of inquiry, and ways of knowing that are central to the discipline(s) s/he teaches.

4(k) The teacher understands common misconceptions in learning the discipline and how to guide learners to accurate conceptual understanding.

4(l) The teacher knows and uses the academic language of the discipline and knows how to make it accessible to learners.

4(m) The teacher knows how to integrate culturally relevant content to build on learners’ background knowledge.

4(n) The teacher has a deep knowledge of student content standards and learning progressions in the discipline(s) s/he teaches.

Critical Dispositions

4(o) The teacher realizes that content knowledge is not a fixed body of facts but is complex, culturally situated, and ever evolving. S/he keeps abreast of new ideas and understandings in the field.

4(p) The teacher appreciates multiple perspectives within the discipline and facilitates learners’ critical analysis of these perspectives.

4(q) The teacher recognizes the potential of bias in his/her representation of the discipline and seeks to appropriately address problems of bias.

4(r) The teacher is committed to work toward each learner’s mastery of disciplinary content and skills.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 6: Trauma-informed educators understand the primacy of attachment theory, and its emphasis on attunement, to the neural development of both students and adults throughout the lifespan.

Disposition 15: Trauma-informed educators understand how to weave Connecting and Coaching practices into academic lesson plans, as the learning process, both the process of learning and the content to master, is also crucial to the integration of neural networks impacted by unmitigated stress and trauma.

Standard 5: Application of Content

The teacher understands how to connect concepts and use differing perspectives to engage learners in critical thinking creativity, and collaborative problem solving related to authentic local and global issues.

Performances

5(a) The teacher develops and implements projects that guide learners in analyzing the complexities of an issue or question using perspectives from varied disciplines and cross-disciplinary skills (e.g., a water quality study that draws upon biology and chemistry to look at factual information and social studies to examine policy implications).

5(b) The teacher engages learners in applying content knowledge to real world problems through the lens of interdisciplinary themes (e.g., financial literacy, environmental literacy).

5(c) The teacher facilitates learners’ use of current tools and resources to maximize content learning in varied contexts.

5(d) The teacher engages learners in questioning and challenging assumptions and approaches in order to foster innovation and problem solving in local and global contexts.

5(e) The teacher develops learners’ communication skills in disciplinary and interdisciplinary contexts by creating meaningful opportunities to employ a variety of forms of communication that address varied audiences and purposes.

5(f) The teacher engages learners in generating and evaluating new ideas and novel approaches, seeking inventive solutions to problems, and developing original work.

5(g) The teacher facilitates learners’ ability to develop diverse social and cultural perspectives that expand their understanding of local and global issues and create novel approaches to solving problems.

5(h) The teacher develops and implements supports for learner literacy development across content areas.

Essential Knowledge

5(i) The teacher understands the ways of knowing in his/her discipline how it relates to other disciplinary approaches to inquiry and the strengths and limitations of each approach in addressing problems, issues, and concerns.

5(j) The teacher understands how current interdisciplinary themes (e.g., civic literacy, health literacy, global awareness) connect to the core subjects and knows how to weave those themes into meaningful learning experiences.

5(k) The teacher understands the demands of accessing and managing information as well as how to evaluate issues of ethics and quality related to information and its use.

5(l) The teacher understands how to use digital and interactive technologies for efficiently and effectively achieving specific learning goals.

5(m) The teacher understands critical thinking processes and knows how to help learners develop high-level questioning skills to promote their independent learning.

5(n) The teacher understands communication modes and skills as vehicles for learning (e.g., information gathering and processing) across disciplines as well as vehicles for expressing learning.

5(o) The teacher understands creative thinking processes and how to engage learners in producing original work.

5(p) The teacher knows where and how to access resources to build global awareness and understanding, and how to integrate them into the curriculum.

Critical Dispositions

5(q) The teacher knows where and how to access resources to build global awareness and understanding, and how to integrate them into the curriculum.

5(r) The teacher values knowledge outside his/her own content area and how such knowledge enhances student learning.

5(s) The teacher values flexible learning environments that encourage learner exploration, discovery, and expression across content areas.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 2: Trauma-informed educators commit to learning the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required to implement trauma-informed practices according to their role and context in order to promote safe and effective learning communities.

Standard 6: Assessment

The teacher understands and uses multiple methods of assessment to engage learners in their own growth, to monitor learner progress, and to guide the teacher’s and learner’s decision making.

Performances

6(a) The teacher balances the use of formative and summative assessment as appropriate to support, verify, and document learning.

6(b) The teacher designs assessments that match learning objectives with assessment methods and minimizes sources of bias that can distort assessment results.

6(c) The teacher works independently and collaboratively to examine test and other performance data to understand each learner’s progress and to guide planning.

6(d) The teacher engages learners in understanding and identifying quality work and provides them with effective descriptive feedback to guide their progress toward that work.

6(e) The teacher engages learners in multiple ways of demonstrating knowledge and skill as part of the assessment process.

6(f) The teacher models and structures processes that guide learners in examining their own thinking and learning as well as the performance of others.

6(g) The teacher effectively uses multiple and appropriate types of assessment data to identify each student’s learning needs and to develop differentiated learning experiences.

6(h) The teacher prepares all learners for the demands of particular assessment formats and makes appropriate accommodations in assessments or testing conditions, especially for learners with disabilities and language learning needs.

6(i) The teacher continually seeks appropriate ways to employ technology to support assessment practice both to engage learners more fully and to assess and address learner needs.

Essential Knowledge

6(j) The teacher understands the differences between formative and summative applications of assessment and knows how and when to use each.

6(k) The teacher understands the range of types and multiple purposes of assessment and how to design, adapt, or select appropriate assessments to address specific learning goals and individual differences, and to minimize sources of bias.

6(l) The teacher knows how to analyze assessment data to understand patterns and gaps in learning, to guide planning and instruction, and to provide meaningful feedback to all learners.

6(m) The teacher knows when and how to engage learners in analyzing their own assessment results and in helping to set goals for their own learning.

6(n) The teacher understands the positive impact of effective descriptive feedback for learners and knows a variety of strategies for communicating this feedback.

6(o) The teacher knows when and how to evaluate and report learner progress against standards.

6(p) The teacher understands how to prepare learners for assessments and how to make accommodations in assessments and testing conditions, especially for learners with disabilities and language learning needs.

Critical Dispositions

6(q) The teacher is committed to engaging learners actively in assessment processes and to developing each learner’s capacity to review and communicate about their own progress and learning.

6(r) The teacher takes responsibility for aligning instruction and assessment with learning goals.

6(s) The teacher is committed to providing timely and effective descriptive feedback to learners on their progress.

6(t) The teacher is committed to using multiple types of assessment processes to support, verify, and document learning.

6(u) The teacher is committed to making accommodations in assessments and testing conditions, especially for learners with disabilities and language learning needs.

6(v) The teacher is committed to the ethical use of various assessments and assessment data to identify learner strengths and needs to promote learner growth.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 2: Trauma-informed educators commit to learning the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required to implement trauma-informed practices according to their role and context in order to promote safe and effective learning communities.

Disposition 12: Trauma-informed educators are aware that students process unmitigated stress and trauma in both direct and indirect ways as they engage in all aspects of the trauma-informed educational environment, and are able to offer an attuned and mentoring response.

Disposition 15: Trauma-informed educators understand how to weave Connecting and Coaching practices into academic lesson plans, as the learning process, both the process of learning and the content to master, is also crucial to the integration of neural networks impacted by unmitigated stress and trauma.

Standard 7: Planning for Instruction

The teacher plans instruction that supports every student in meeting rigorous learning goals by drawing upon knowledge of content areas, curriculum, cross-disciplinary skills, and pedagogy, as well as knowledge of learners and the community context.

Performances

7(a) The teacher individually and collaboratively selects and creates learning experiences that are appropriate for curriculum goals and content standards, and are relevant to learners.

7(b) The teacher plans how to achieve each student’s learning goals, choosing appropriate strategies and accommodations, resources, and materials to differentiate instruction for individuals and groups of learners.

7(c) The teacher develops appropriate sequencing of learning experiences and provides multiple ways to demonstrate knowledge and skill.

7(d) The teacher plans for instruction based on formative and summative assessment data, prior learning knowledge, and learner interest.

7(e) The teacher plans collaboratively with professionals who have specialized expertise (e.g., special educators, related service providers, language learning specialists, librarians, media specialists) to design and jointly deliver as appropriate effective learning experiences to meet unique learning needs.

7(f) The teacher evaluates plans in relation to short- and long-range goals and systematically adjusts plans to meet each student’s learning needs and enhance learning.

Essential Knowledge

7(g) The teacher understands content and content standards and how these are organized in the curriculum.

7(h) The teacher understands how integrating cross-disciplinary skills in instruction engages learners purposefully in applying content knowledge.

7(i) The teacher understands learning theory, human development, cultural diversity, and individual differences and how these impact ongoing planning.

7(j) The teacher understands the strengths and needs of individual learners and how to plan instruction that is responsive to these strengths and needs.

7(k) The teacher knows a range of evidence-based instructional strategies, resources, and technological tools and how to use them effectively to plan instruction that meets diverse learning needs.

7(l) The teacher knows when and how to adjust plans based on assessment information and learner responses.

7(m) The teacher knows when and how to assess resources and collaborate with others to support student learning (e.g., special educators, related service providers, language learner specialists, librarians, media specialists, community organizations).

Critical Dispositions

7(n) The teacher respects learners’ diverse strengths and needs and is committed to using this information to plan effective instruction.

7(o) The teacher values planning as a collegial activity that takes into consideration the input of learners, colleagues, families, and the larger community.

7(p) The teacher takes professional responsibility to use short- and long-term planning as a means of assuring student learning.

7(q) The teacher believes that plans must always be open to adjustment and revision based on learner needs and changing circumstances.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 3: Trauma-informed educators are committed to embedding trauma-informed rituals and practices within the daily, weekly, and seasonal routines of a school and classroom providing a sense of repetition that deepens internal safety and stabilization. Repetition also emphasizes that basic TISP building blocks are continual and constant, not merely a phase that is completed in order to move to the next phase.

Disposition 6: Trauma-informed educators understand the primacy of attachment theory, and its emphasis on attunement, to the neural development of students and adults throughout the lifespan.

Disposition 9: Trauma-informed educators understand the primacy of attachment theory, and its emphasis on mentoring, to the neural development of students and adults throughout the lifespan.

Disposition 10: Trauma-informed educators understand that student behavior, in part, is often a reflection of unintegrated neural networks due to past and/or current unmitigated stress and trauma, and require the student to first establish a sense of safety and stability prior to commencing with here-and-now developmental expectations.

Disposition 11: Trauma-informed educators understand that persons all along the lifespan are influenced by past experiences shaping perceptions and emotional responses. It is a lifelong task to understand this connection while learning to self-regulate in the face of intense emotional responses to current events.

Disposition 12: Trauma-informed educators are aware that students process unmitigated stress and trauma in both direct and indirect ways as they engage in all aspects of the trauma-informed educational environment, and are able to offer an attuned and mentoring response.

Disposition 15: Trauma-informed educators understand how to weave Connecting and Coaching practices into academic lesson plans, as the learning process, both the process of learning and the content to master, is also crucial to the integration of neural networks impacted by unmitigated stress and trauma.

Standard 8: Instructional Strategies

The teacher understands and uses a variety of instructional strategies to encourage learners to develop deep understanding of content areas and their connections, and to build skills to apply knowledge in meaningful ways.

Performances

8(a) The teacher uses appropriate strategies and resources to adapt instruction to the needs of individual and groups of learners.

8(b) The teacher continuously monitors student learning, engages learners in assessing their progress, and adjusts instruction in response to student learning needs.

8(c) The teacher collaborates with learners to design and implement relevant learning experiences, identify their strengths, and access family and community resources to develop their areas of interest.

8(d) The teacher varies his/her role in the instructional process (e.g., instructor, facilitator, coach, audience) in relation to the content and purposes of instruction and the needs of learners.

8(e) The teacher provides multiple models and representations of concepts and skills with opportunities for learners to demonstrate their knowledge through a variety of products and performances.

8(f) The teacher engages all learners in developing higher-order questioning skills and metacognitive processes.

8(g) The teacher engages learners in using a range of learning skills and technology tools to access, interpret, evaluate, and apply information.

8(h) The teacher uses a variety of instructional strategies to support and expand learners’ communication through speaking, listening, reading, writing, and other models.

8(i) The teacher asks questions to stimulate discussion that serves different purposes (e.g., probing for learner understanding, helping learners articulate their ideas and thinking processes, stimulating curiosity, and helping learners to question).

Essential Knowledge

8(j) The teacher understands the cognitive processes associated with various kinds of learning (e.g., critical and creative thinking, problem framing and problem solving, invention, memorization and recall) and how these processes can be stimulated.

8(k) The teacher knows how to apply a range of developmentally culturally, and linguistically appropriate instructional strategies to achieve learning goals.

8(l) The teacher knows when and how to use appropriate strategies to differentiate instruction and engage all learners in complex thinking and meaningful tasks.

8(m) The teacher understands how multiple forms of communication (oral, written, nonverbal, digital, visual) convey ideas, foster self-expression, and build relationships.

8(n) The teacher knows how to use a wide variety of resources, including human and technological, to engage students in learning.

8(o) The teacher understands how content and skill development can be supported by media and technology and knows how to evaluate these resources for quality, accuracy, and effectiveness.

Critical Dispositions

8(p) The teacher is committed to deepening awareness and understanding the strengths and needs of diverse learners when planning and adjusting instruction.

8(q) The teacher values the variety of ways people communicate and encourages learners to develop and use multiple forms of communication.

8(r) The teacher is committee to exploring how the use of new and emerging technologies can support and promote student learning.

8(s) The teacher values flexibility and reciprocity in the teaching process as necessary for adapting instruction to learner responses, ideas, and needs.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 3: Trauma-informed educators are committed to embedding trauma-informed rituals and practices within the daily, weekly, and seasonal routines of a school and classroom providing a sense of repetition that deepens internal safety and stabilization. Repetition also emphasizes that basic TISP building blocks are continual and constant, not merely a phase that is completed in order to move to the next phase.

Disposition 9: Trauma-informed educators understand the primacy of attachment theory, and its emphasis on mentoring, to the neural development of students and adults throughout the lifespan.

Disposition 10: Trauma-informed educators understand that student behavior, in part, is often a reflection of unintegrated neural networks due to past and/or current unmitigated stress and trauma, and require the student to first establish a sense of safety and stability prior to commencing with here-and-now developmental expectations.

Disposition 11: Trauma-informed educators understand that persons all along the lifespan are influenced by past experiences shaping perceptions and emotional responses. It is a lifelong task to understand this connection while learning to self-regulate in the face of intense emotional responses to current events.

Disposition 15: Trauma-informed educators understand how to weave Connecting and Coaching practices into academic lesson plans, as the learning process, both the process of learning and the content to master, is also crucial to the integration of neural networks impacted by unmitigated stress and trauma.

Standard 9: Content Knowledge

The teacher engages in ongoing professional learning and uses evidence to continually evaluate his/her practice, particularly the effects of his/her choices and actions on others (learners, families, other professionals, and the community), and adapts practice to meet the needs of each learner.

Performances

9(a) The teacher engages in ongoing learning opportunities to develop knowledge and skills in order to provide all learners with engaging curriculum and learning experiences based on local and state standards.

9(b) The teacher engages in meaningful and appropriate professional learning experiences aligned with his/her own needs and the needs of the learners, school, and system.

9(c) Independently and in collaboration with colleagues, the teacher uses a variety of data (e.g., systematic observation, information about learners, research) to evaluate the outcomes of teaching and learning and to adapt planning and practice.

9(d) The teacher actively seeks professional, community, and technological resources, within and outside the school, as supports for analysis, reflection, and problem-solving.

9(e) The teacher reflects on his/her personal biases and accesses resources to deepen his/her own understanding of cultural, ethnic, gender, and learning differences to build stronger relationships and create more relevant learning experiences.

9(f) The teacher advocates, models, and teaches safe, legal, and ethical use of information and technology including appropriate documentation of sources and respect for others in the use of social media.

Essential Knowledge

9(g) The teacher understands and knows how to use a variety of self-assessment and problem-solving strategies to analyze and reflect on his/her practice and to plan for adaptations/adjustments.

9(h) The teacher knows how to use learner data to analyze practice and differentiate instruction accordingly.

9(i) The teacher understands how personal identity, worldview, and prior experience affect perceptions and expectations, and recognizes how they may bias behaviors and interactions with others

9(j) The teacher understands laws related to learners’ rights and teacher responsibilities (e.g., for educational equity, appropriate education for learners with disabilities, confidentiality, privacy, appropriate treatment of learners, reporting in situations related to possible child abuse).

9(k) The teacher knows how to build and implement a plan for professional growth directly aligned with his/her needs as a growing professional using feedback from teacher evaluations and observations, data on learner performance, and school-and system-wide priorities.

Critical Dispositions

9(l) The teacher takes responsibility for student learning and uses ongoing analysis and reflection to improve planning and practice.

9(m) The teacher is committed to deepening understanding of his/her own frames of reference (e.g., culture, gender, language, abilities, ways of knowing), the potential biases in these frames, and their impact on expectations for and relationships with learners and their families.

9(n) The teacher sees him/herself as a learner, continuously seeking opportunities to draw upon current education policy and research as sources of analysis and reflection to improve practice.

9(o) The teacher understands the expectations of the profession including codes of ethics, professional standards of practice, and relevant law and policy.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 2: Trauma-informed educators commit to learning the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required to implement trauma-informed practices according to their role and context in order to promote safe and effective learning communities.

Standard 10: Leadership and Collaboration

The teacher seeks appropriate leadership roles and opportunities to take responsibility for student learning, to collaborate with learners, families, colleagues, other school professionals, and community members to ensure learner growth, and to advance the profession.

Performances

10(a) The teacher takes an active role on the instructional team, giving and receiving feedback on practice, examining learner work, analyzing data from multiple sources, and sharing responsibility for decision making and accountability for each student’s learning.

10(b) The teacher works with other school professionals to plan and jointly facilitate learning on how to meet diverse needs of learners.

10(c) The teacher engages collaboratively in the school-wide effort to build a shared vision and supportive culture, identify common goals, and monitor and evaluate progress toward those goals.

10(d) The teacher works collaboratively with learners and their families to establish mutual expectations and ongoing communication to support learner development and achievement.

10(e) Working with school colleagues, the teacher builds ongoing connections with community resources to enhance student learning and well-being.

10(f) The teacher engages in professional learning, contributes to the knowledge and skill of others, and works collaboratively to advance professional practice.

10(g) The teacher uses technological tools and a variety of communication strategies to build local and global learning communities that engage learners, families, and colleagues.

10(h) The teacher uses and generates meaningful research on education issues and policies.

10(i) The teacher seeks appropriate opportunities to model effective practice for colleagues, to lead professional learning activities, and to serve in other leadership roles.

10(j) The teacher advocates to meet the needs of learners, to strengthen the learning environment, and to enact system change.

10(k) The teacher takes on leadership roles at the school, district, state, and/or national level and advocates for learners, the school, the community, and the profession.

Essential Knowledge

10(l) The teacher understands schools as organizations within a historical, cultural, political, and social context and knows how to work with others across the system to support learners.

10(m) The teacher understands that alignment of family, school, and community spheres of influence enhances student learning and that discontinuity in these spheres of influence interferes with learning.

10(n) The teacher knows how to work with other adults and has developed skills in collaborative interaction appropriate for both face-to-face and virtual contexts.

10(o) The teacher knows how to contribute to a common culture that supports high expectations for student learning.

Critical Dispositions

10(p) The teacher actively shares responsibility for shaping and supporting the mission of his/her school as one of advocacy for learners and accountability for their success.

10(q) The teacher respects families’ beliefs, norms, and expectations and seeks to work collaboratively with learners and families in setting and meeting challenging goals.

10(r) The teacher takes initiative to grow and develop with colleagues through interactions that enhance practice and support student learning.

10(s) The teacher takes responsibility for contributing to and advancing the profession.

10(t) The teacher embraces the challenge of continuous improvement and change.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 2: Trauma-informed educators commit to learning the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required to implement trauma-informed practices according to their role and context in order to promote safe and effective learning communities.

Disposition 8: Trauma-informed educators recognize that the success of trauma-informed practices requires involvement and support from all levels of the school system: administration, school, staff, classroom (including students), and community (school board and caretakers).

Table 11.1

There is a similar set of standards for building- and district-level administrators, titled the National Educational Leadership Preparation (NELP) standards; these are listed in Table 11.2. For brevity, we chose to focus on building-level administrators only, as these and the District Strategic Planning Team tasks highlighted in Chapter 7 illuminate parallel district-level standards. We specifically chose to highlight administrative standards since trauma-informed leadership is paramount to successfully transforming District and School practices. Like the InTASC standards, the NELP standards do not specifically identify the impact of unmitigated stress and trauma on a student’s readiness to learn. As with the InTASC standards, we recommend the inclusion of trauma-informed dispositions in administrator standards and preparation programs.

Table 11.2: NELP Standards with Trauma-Informed School Practices Dispositions

Standard 1: Mission, Vision, and Improvement

Candidates who successfully complete a building-level educational leadership preparation program understand and demonstrate the capacity to promote the current and future success and well-being of each student and adult by applying the knowledge, skills, and commitments necessary to collaboratively lead, design, and implement a school mission, vision, and process for continuous improvement that reflects a core set of values and priorities.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 17: Trauma-Informed educators advocate on local, state, and national levels for greater understanding of the neurobiological impacts on a student when either (a) the student cannot self-regulate or (b) the student is repeatedly exposed to peers unable to self-regulate, leading to frequent episodes of classroom disruption. This constant state of dysregulation and exposure to peers in such states cause more stress and trauma for all students.

Standard 2: Ethics and Professional Norms

Candidates who successfully complete a building-level educational leadership preparation program understand and demonstrate the capacity to promote the current and future success and well-being of each student and adult by applying the knowledge, skills, and commitments necessary to understand and demonstrate the capacity to advocate for ethical decisions and cultivate and enact professional norms.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 5: Trauma-informed educators are committed to a consistent ethic of care whereby the relational values offered to students are extended to self and one another

Disposition 7: Trauma-informed educators are committed to attending to Person of the Educator wellness practices in recognition of their vulnerability to secondary trauma and compassion fatigue. This includes a commitment to understanding their own relational and developmental history influencing their own neural integration, foundational to strengthening resilience and well-being.

Disposition 8: Trauma-informed educators recognize that the success of trauma-informed practices requires involvement and support from all levels of the school system: administration, school, staff, classroom (including students), and community (school board and caretakers).

Disposition 17: Trauma-informed educators advocate on local, state, and national levels for greater understanding of the neurobiological impacts on a student when either (a) the student cannot self-regulate or (b) the student is repeatedly exposed to peers unable to self-regulate, leading to frequent episodes of classroom disruption. This constant state of dysregulation and exposure to peers in such states cause more stress and trauma for all students.

Standard 3: Equity, Inclusiveness, and Cultural Responsiveness

Candidates who successfully complete a building-level educational leadership preparation program understand and demonstrate the capacity to promote the current and future success and well-being of each student and adult by applying the knowledge, skills, and commitments necessary to develop and maintain a supportive, equitable, culturally responsive, and inclusive school culture.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 1: Trauma-informed educators create environments that promote the neural integration of their members (students and educators) in order to maximize students’ academic and social success at each developmental stage.

Disposition 2: Trauma-informed educators commit to learning the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required to implement trauma-informed practices according to their role and context in order to promote safe and effective learning communities.

Disposition 3: Trauma-informed educators are committed to embedding trauma-informed rituals and practices within the daily, weekly, and seasonal routines of a school and classroom, providing a sense of repetition that deepens internal safety and stabilization. Repetition also emphasizes that basic TISP building blocks are continual and constant, not merely a phase that is completed in order to move to the next phase.

Disposition 4: Trauma-informed educators are aware of socio-cultural factors that increase student risk or resilience, and are committed to creating an educational environment that is welcoming, safe, and inclusive of all persons.

Disposition 5: Trauma-informed educators are committed to a consistent ethic of care whereby the relational values offered to students are extended to self and one another.

Disposition 6: Trauma-informed educators understand the primacy of attachment theory, and its emphasis on attunement, to the neural development of students and adults throughout the lifespan.

Disposition 7: Trauma-informed educators are committed to attending to Person of the Educator wellness practices in recognition of their vulnerability to secondary trauma and compassion fatigue. This includes a commitment to understanding their own relational and developmental history influencing their own neural integration, foundational to strengthening resilience and well-being.

Disposition 8: Trauma-informed educators recognize that the success of trauma-informed practices requires involvement and support from all levels of the school system: administration, school, staff, classroom (including students), and community (school board and caretakers).

Disposition 10: Trauma-informed educators understand that student behavior, in part, is often a reflection of unintegrated neural networks due to past and/or current unmitigated stress and trauma, and require the student to first establish a sense of safety and stability prior to commencing with here-and-now developmental expectations.

Disposition 11: Trauma-informed educators understand that persons all along the lifespan are influenced by past experiences shaping perceptions and emotional responses. It is a lifelong task to understand this connection while learning to self-regulate in the face of intense emotional responses to current events.

Disposition 12: Trauma-informed educators are aware that students process unmitigated stress and trauma in both direct and indirect ways as they engage in all aspects of the trauma-informed educational environment, and are able to offer an attuned and mentoring response.

Disposition 13: Trauma-informed educators are skilled in attuning to grief and mourning responses that often accompany academic engagement as neural networks integrate, which allow for deeper connection to memory and its meaning to occur.

Disposition 14: Trauma-informed education systems include licensed mental health professionals available for students requesting or needing access to professional trauma-informed recovery services.

Disposition 15: Trauma-informed educators understand how to weave Connecting and Coaching practices into academic lesson plans, as the learning process, both the process of learning and the content to master, is also crucial to the integration of neural networks impacted by unmitigated stress and trauma.

Disposition 16: Trauma-informed educators understand the nature of a student’s academic and social-emotional functioning in the classroom, and how best to meet the individual needs of each student, whether in a traditional classroom or with additional assistance.

Disposition 17: Trauma-informed educators advocate on local, state, and national levels for greater understanding of the neurobiological impacts on a student when either (a) the student cannot self-regulate or (b) the student is repeatedly exposed to peers unable to self-regulate leading to frequent episodes of classroom disruption. This constant state of dysregulation and exposure to peers in such states cause more stress and trauma for all students.

Standard 4: Learning and Instruction

Candidates who successfully complete a building-level educational leadership preparation program understand and demonstrate the capacity to promote the current and future success and wellbeing of each student and adult by applying the knowledge, skills, and commitments necessary to evaluate, develop, and implement coherent systems of curriculum, instruction, supports, and assessment.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 1: Trauma-informed educators create environments that promote the neural integration of their members (students and educators) in order to maximize students’ academic and social success at each developmental stage.

Disposition 2: Trauma-informed educators commit to learning the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required to implement trauma-informed practices according to their role and context in order to promote safe and effective learning communities.

Disposition 3: Trauma-informed educators are committed to embedding trauma-informed rituals and practices within the daily, weekly, and seasonal routines of a school and classroom providing a sense of repetition that deepens internal safety and stabilization. Repetition also emphasizes that basic TISP building blocks are continual and constant, not merely a phase that is completed in order to move to the next phase.

Disposition 4: Trauma-informed educators are aware of socio-cultural factors that increase student risk or resilience, and are committed to creating an educational environment that is welcoming, safe, and inclusive of all persons.

Disposition 5: Trauma-informed educators are committed to a consistent ethic of care whereby the relational values offered to students are extended to self and one another

Disposition 8: Trauma-informed educators recognize that the success of trauma-informed practices requires involvement and support from all levels of the school system: administration, school, staff, classroom (including students), and community (school board and caretakers).

Disposition 10: Trauma-informed educators understand that student behavior, in part, is often a reflection of unintegrated neural networks due to past and/or current unmitigated stress and trauma, and require the student to first establish a sense of safety and stability prior to commencing with here-and-now developmental expectations.

Disposition 11: Trauma-informed educators understand that persons all along the lifespan are influenced by past experiences shaping perceptions and emotional responses. It is a lifelong task to understand this connection while learning to self-regulate in the face of intense emotional responses to current events.

Disposition 12: Trauma-informed educators are aware that students process unmitigated stress and trauma in both direct and indirect ways as they engage in all aspects of the trauma-informed educational environment, and are able to offer an attuned and mentoring response.

Disposition 14: Trauma-informed education systems include licensed mental health professionals available for students requesting or needing access to professional trauma-informed recovery services.

Disposition 15: Trauma-informed educators understand how to weave Connecting and Coaching practices into academic lesson plans, as the learning process, both the process of learning and the content to master, is also crucial to the integration of neural networks impacted by unmitigated stress and trauma.

Disposition 16: Trauma-informed educators understand the nature of a student’s academic and social-emotional functioning in the classroom, and how best to meet the individual needs of each student, whether in a traditional classroom or with additional assistance.

Disposition 17: Trauma-informed educators advocate on local, state, and national levels for greater understanding of the neurobiological impacts on a student when either (a) the student cannot self-regulate or (b) the student is repeatedly exposed to peers unable to self-regulate leading to frequent episodes of classroom disruption. This constant state of dysregulation and exposure to peers in such states cause more stress and trauma for all students.

Standard 5: Community and External Leadership

Candidates who successfully complete a building-level educational leadership preparation program understand and demonstrate the capacity to promote the current and future success and well-being of each student and adult by applying the knowledge, skills, and commitments necessary to engage families, community, and school personnel in order to strengthen student learning, support school improvement, and advocate for the needs of their school and community.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 5: Trauma-informed educators are committed to a consistent ethic of care whereby the relational values offered to students are extended to self and one another

Disposition 8: Trauma-informed educators recognize that the success of trauma-informed practices requires involvement and support from all levels of the school system: administration, school, staff, classroom (including students), and community (school board and caretakers).

Disposition 14: Trauma-informed education systems include licensed mental health professionals available for students requesting or needing access to professional trauma-informed recovery services.

Disposition 17: Trauma-informed educators advocate on local, state, and national levels for greater understanding of the neurobiological impacts on a student when either (a) the student cannot self-regulate or (b) the student is repeatedly exposed to peers unable to self-regulate leading to frequent episodes of classroom disruption. This constant state of dysregulation and exposure to peers in such states cause more stress and trauma for all students.

Standard 6: Operations and Management

Candidates who successfully complete a building-level educational leadership preparation program understand and demonstrate the capacity to promote the correct and future success and well-being of each student and adult by applying the knowledge, skills and commitments necessary to improve management, communication, technology, school-level governance, and operation systems to develop and improve data-informed and equitable school resource plans and to apply laws, policies, and regulations.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 17: Trauma-informed educators advocate on local, state, and national levels for greater understanding of the neurobiological impacts on a student when either (a) the student cannot self-regulate or (b) the student is repeatedly exposed to peers unable to self-regulate leading to frequent episodes of classroom disruption. This constant state of dysregulation and exposure to peers in such states cause more stress and trauma for all students.

Standard 7: Building Professional Capacity

Candidates who successfully complete a building-level educational leadership preparation program understand and demonstrate the capacity to promote the current and future success and well-being of each student and adult by applying the knowledge, skills, and commitments necessary to build the school’s professional capacity, engage staff in the development of a collaborative professional culture, and improve systems of staff supervision, evaluation, support, and professional learning.

Trauma-Informed Dispositions

Disposition 2: Trauma-informed educators commit to learning the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required to implement trauma-informed practices according to their role and context in order to promote safe and effective learning communities.

Disposition 3: Trauma-informed educators are committed to embedding trauma-informed rituals and practices within the daily, weekly, and seasonal routines of a school and classroom providing a sense of repetition that deepens internal safety and stabilization. Repetition also emphasizes that basic TISP building blocks are continual and constant, not merely a phase that is completed in order to move to the next phase.

Disposition 4: Trauma-informed educators are aware of socio-cultural factors that increase student risk or resilience, and are committed to creating an educational environment that is welcoming, safe, and inclusive of all persons.

Disposition 8: Trauma-informed educators recognize that the success of trauma-informed practices requires involvement and support from all levels of the school system: administration, school, staff, classroom (including students), and community (school board and caretakers).

Disposition 14: Trauma-informed education systems include licensed mental health professionals available for students requesting or needing access to professional trauma-informed recovery services.

Table 11.2

Advocating for Change

While Districts, Schools, and Educators need training in trauma-informed practice, we propose that ultimately training must take place in teacher and administrative preparation programs, taught by higher education faculty with proven competencies in trauma-informed content and practice domains. Training educators during a preparation program would not only be most cost-effective, but it would allow schools to hire educators trained and ready to meet the needs of all learners.

We are not alone in recognizing the significance of preparing educators in trauma-informed practices. While many U.S. states, as we discuss below, have enacted legislation requiring schools to incorporate trauma-informed practices, movement is also occurring on the national level. For example, in 2017, U.S. Congressman Rodney Davis from Illinois introduced H.R. 1757, the Trauma-Informed Care for Children and Families Act. The bill included multiple strategies to address the impact of trauma and the support families need in response. One of these strategies was requiring higher education programs to expose preservice teachers to trauma-informed curricula in an effort to ensure that all teachers enter the classroom with the ability to recognize and support students impacted by unmitigated stress and trauma. While several aspects of this bill were passed, the higher education trauma-informed training for teachers did not move forward. However, U.S. Senator Durbin from Illinois and Representative Davis are working on reintroducing this, which is encouraging to hear!

While this bill could support all students by requiring trauma-informed education in their preparation programs, it is critical to acknowledge that not all educator preparation programs have faculty who are capable of providing adequate training in this content domain. Additionally, as noted earlier, while mental health providers are expected to be skilled in treating persons impacted by trauma, not all are trained in recent advances in the knowledge and skills comprising the trauma-informed specialty. Therefore, in order for us to train educators capable of implementing trauma-informed practices in schools and classrooms, more higher education faculty (in the fields of education and mental health) would need to develop trauma-informed competencies as they apply to educational settings, and then collaborate together to train the next generation of educators capable of trauma-informed practice.

In addition to the legislation mentioned, we wanted to point out other significant work being done in several states. As of 2019, 12 states (California, Illinois, Indiana, Massachusetts, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, and Washington) and the District of Columbia have either initiated or passed legislation to support their citizens impacted by trauma. The scope of these bills ranges from trauma-informed care for communities to specific training for in-service teachers on trauma-informed practices. Our own state of Oregon passed a bill focused on reducing absenteeism by providing trauma-informed training in a pilot model. The goal was to advance educator knowledge regarding the impact of unmitigated stress and trauma in an effort to reduce the dropout rate by encouraging school attendance.

Chapter 11: Exercise

Exercise: Conceptual Application—Questions to Ponder

Details of a competency, whether listed according to specific knowledge, skills, and dispositions such as in the Trauma-Informed School Practices Tri-Phasic Model detailed in Chapter 6, or thematically summarized as proposed here within current InTASC standards, are content-dense materials. The TISP Tri-Phasic Model identifies how trauma-informed educator practice is a scaffolded and iterative three-phase education approach, embedded with its own content domains and practice standards; it is a paradigm shift revealed in school culture, not just classroom management strategies. It guides higher education teacher preparation programs in crafting specific elements of trauma-informed coursework, and educational settings when transitioning districts and schools to a trauma-informed model. The InTASC proposed standards in Table 11.1 summarize the dispositions of the TISP specialty as they might appear in accreditation documents.

Take a moment to reread Table 11.1 as well as the TISP Tri-Phasic Model in Chapter 6, and reflect on the following questions:

- Consider the trauma-informed dispositions listed in the TISP Tri-Phasic Model and woven into the InTASC proposed standards. We have also listed these dispositions in Appendix D. These dispositions represent key outcomes acquired as a result of mastering the content domains of trauma-informed practice.

- Identify dispositions you see as a fit for trauma-informed educator practice.

- Likewise, identify dispositions that you question its fit for TISP.

- Identify dispositions not listed.

- Identify dispositions you would recommend adding.

- As you review the InTASC proposed standards, do you agree with the placement of dispositions for each standard? This cross-checking process may also help you identify revisions to the list or wording of various dispositions.

- Each person reading this text is in a unique role. Some of you may be in teacher or administrator credentialing programs; some may be preparing for mental health practice within school settings; others may be engaged in various stages of trauma-informed educator practice as credentialed or unclassified educators; some may not be working with students directly, but assume administrative roles. Others may be higher education professionals preparing education and mental health professionals, or legislators or lobbyists serving the public education needs of your community. Based on your current professional identity, role, and context, ponder the following questions:

- What does professional advocacy mean to you, and how do you see the education profession expecting or needing its members to be advocates for the profession as a whole, for its members, and for the students we serve?

- What types of advocacy are your strengths and preferences?

- This text illustrates that trauma-informed educator practice is more than merely adopting new classroom strategies: it requires the entire educational system to update its preparation and practice standards. What type or level of advocacy do you think is currently needed for the education profession to update its current preparation and practice standards in response?

- What type of advocacy might you engage in, and whom might you network with for support and camaraderie?

A Look Forward

Our concluding chapter addresses data-gathering needs, with an emphasis on evaluating staff and student engagement with trauma-informed education environments. We close our time together with a look at specific ways you can respond to the personal stress and challenges of serving students often overwhelmed by the stress and uncertainty in their own lives.

Resources for Further Reading

- American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education. This website provides resources for teacher education programs, and focuses primarily on policy.

- Association of Teacher Educators. This website provides resources for teacher preparation.