12

“It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data.” —Sherlock Holmes

Desired Outcomes

We conclude our examination of developing TISP competencies by tending to key themes ensuring its efficacy and sustainability. This chapter and the accompanying recommended readings and activities are designed to further develop educator trauma-informed competencies as demonstrated by:

- An awareness of internal and external factors that contribute to an educator’s commitment to TISP practice, along with the ability to identify strategies to strengthen sustained engagement in the TISP transition process

- The ability to identify the importance of gathering outcome data assessing the cumulative impact of trauma-informed practices

- A recognition that Person of the Educator knowledge, skills, and dispositions represent a commitment to the health and well-being of coworkers given the risks of compassion fatigue and burnout associated with the education profession

Key Concepts

We began our text with an acknowledgement that without proper training and support, TISP can easily become a fad or be viewed as impractical. But the severity of need and the trauma-informed literature are compelling us to act. Here we address Phase III Commencing activities to ensure that we continue in our TI transition processes. This chapter includes the following key concepts foundational to sustaining TISP practices:

- The interconnections between educators’ perceived need and urgency, attitudes and dispositions, trauma-informed knowledge, and larger system support in predicting and monitoring TISP interest and sustained application

- The importance of gathering data tracking student engagement and learning in a trauma-informed school setting

- The risks and prevention of compassion fatigue as part of Person of the Educator concerns

Chapter Overview

In Section II we identified that our strategic plans have immediate, short-range, and long-range agenda items. Sustaining TISP requires awareness of factors contributing to its long-term success as well as specific action items, and our initial glimpse of the long-term agenda items (congruent with TISP Tri-Phasic Model Phase III tasks) allowed us to lay the groundwork for tending to sustainability concerns. Now is the time to place these agenda items on the front burner.

We begin by revisiting the survey you took in the beginning of this text and identifying its elements that provide insight into vulnerabilities threatening sustained commitment to transforming schools throughout a district. We then address the role of data gathering, not just in support of key stakeholders who require evidence of our success, but to affirm for educators that our efforts are creating safety and stability prerequisite to student learning. We conclude our work with an awareness that educator burnout and compassion fatigue are professional risk factors that are both logical, given the severity of need in today’s schools, and preventable.

Tracking and Nurturing Staff Motivation and Resources

In the Preface of this text, you were invited to take a survey exploring your perceptions and concerns regarding the challenges of educating today’s students and the feasibility of changing school practices to a trauma-informed model. We invite you to pause now and retake this survey using this same link (TISP Implementation Predictors Survey).

In Section I, we examined key aspects of resilience as we introduced Antonovsky’s concept of the sense of coherence, that aspect of our core identity comprised of how we make sense of the world and how the world does or should work. This influences our sense of competence in figuring out how to act with intentionality to maximize the likelihood of successful coping. Whenever a system or an individual is asked to reorient their core understanding regarding how something works, it challenges their SOC creating varying amounts of dissonance and discomfort. Too little dissonance and we can ignore the discomfort as a passing trend. Too much dissonance and we will engage in a fight, flight, or freeze response. This is similar to Vygotsky’s window of tolerance (Kraus, 2009; Mooney, 2013; Wikipedia Contributors, 2018).

The explosion of insight into the mechanisms of unmitigated stress and trauma and the physiological, emotional, and social consequences to human development and functioning over the lifespan is such a challenge. It is requiring the profession of education to reorient itself from the ground up, including teacher and administrator content domains spanning classroom management strategies, pedagogy and related techniques, child development theories, leadership training, and supervision and mentoring processes. It is inviting change in how we view and work with each other, regardless of our role, and it is requiring change in the way we interact with our students. TISP is a big rock that has dropped into a very still pond, and the waves of dissonance are likely to create a stress response.

Zooming Our Lens Out for the Larger Context

Part of what has motivated us to create the TISP Tri-Phasic Model and to write this textbook is knowing that students and educators are suffering due to larger social forces eroding individual and community health and well-being, further affecting students’ readiness to learn. ACE scores are just the end product or the tip of the iceberg, in the same way as any indicator of an impending breakdown or disaster. We view trauma-informed advances as providing a window into how we can respond in our own small way to effect big change in the lives of the people we serve, regardless of our professional role.

But we see no way around this shift causing significant dissonance. We have watched a variety of dedicated trauma-informed educators make great strides in ushering schools through the trauma-informed change process, and we have also watched a significant number of schools and educators experience frustration or disbelief in the viability or wisdom of changing an entire system. It is all too common for classroom teachers to be sent to a seminar providing a list of strategies, and then for administrators to expect those strategies to be implemented the next day, with the expectation that great results will suddenly appear. In some of these scenarios, there is little awareness that perhaps the administrator needs to set up changes first, in support of classroom teachers who are being asked to re-evaluate their classroom practices from top to bottom. We have watched and experienced classroom teachers seeing this as yet another trend and bowing out of any such trainings; we have watched both new and experienced teachers resonate with the initial ethos and attend the speed trainings, only to ride a roller coaster of hope, frustration, and disillusionment. The dashed hope sometimes arises from a lack of clear or grounded trauma-informed training; the educator is given a set of techniques without a conceptual foundation, and those techniques wear out their welcome and no longer work. In other instances, it is the School or District system’s lack of understanding that a trauma-informed classroom has a very tenuous existence when the entire system is not engaged in the change process. The dashed hope sometimes arises from a lack of clear or grounded trauma-informed training; the educator is given a set of techniques without a conceptual foundation, and those techniques wear out their welcome and no longer work. In other instances, it is the School or District system’s lack of understanding that a trauma-informed classroom has a very tenuous existence when the entire system is not engaged in the change process.

The change process is further compounded by the fact that the Regulatory and Support Systems (accrediting and professional organizations, higher education training programs, and legal statutes governing the profession) responsible for maintaining professional educator standards have not yet required changes to training curriculums to adequately identify and facilitate TISP competencies in their graduates. Despite trauma-informed competencies arising from within the social and behavioral science professions, much work remains in changing mental health graduate training programs to require trauma-informed competencies (beyond psychotherapeutic practices common to everyday practice) as well.

We mention these challenges again, as we did in Section II, because the process of creating system change is complex and takes time. For every frustration, we see further movement ahead. None of the challenges we listed thus far are unexpected or even avoidable in the early stages of a paradigm change. Our aim is to clearly name these complex issues and target responses to help facilitate the next steps of the change process. We also want to validate your frustration and affirm that you, your school, and your district are not doing anything “wrong”; they are not to blame; you are not to blame. This is a new process; changing the direction of the Titanic is not going to occur without scrapes, bumps, and bruises. We want to prevent the education equivalent of a sinking ship by zooming out to see the big picture and then zooming in on our own pieces that we can control.

What you can control is congruent with your current role. If you are in a teacher or administrator preparation program, you can commit to mastering TISP competencies that you then bring to Districts who have made the transition or desire to do so. If you are currently an educator, of course TISP will change your mindset and give you ideas regarding how you can change your daily routines. But you may also have a larger field of influence than you think. We are inviting all educators, whether still in training or working in the profession, to see both the larger picture and your own backyard; it is not either/or but both/and, and you have the capacity to inspire system change. We hope that seeing the larger picture—it does get messy, it’s unpredictable, and it takes time to climb this mountain—actually inspires you to relax, think strategically, and take it step by step.

Elements of Successful and Sustainable TISP Implementation

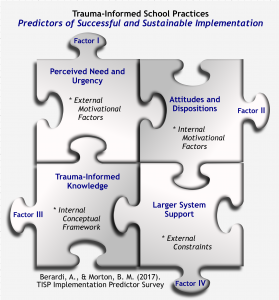

The Predictors of Successful and Sustainable TISP Implementation survey is designed to act as a tracking device to monitor the pulses of us mountaineers. The survey, used as a pre- and post-assessment device, is designed to observe District, School, and Educator processes, and to predict the likelihood of educational settings building sustainable trauma-informed cultures, given the complexity of this challenge as just highlighted. The survey identifies four elements of successful implementation and sustaining of TISP, summarized in Figure 12.1.

Figure 12.1 Predictors of Successful and Sustainable TISP Implementation

These four elements are proposed predictors of a successful and sustainable transition to TISP. The interlocking puzzle pieces in Figure 12.1 indicate that each element influences and is influenced by the other elements.

Perceived Need and Urgency is perhaps the most significant contributor to motivating us to change. While it expresses a subjective sense of discomfort, it is based on external realities. We know that America’s public education system is under assault. The more that classrooms are in crisis, the more parents with access pull their kids out of those schools, and the less the general public feels committed to investing in the next generation of citizens. To legitimize taking away funds, we blame schools for being inadequate stewards of taxpayer dollars. Most specifically, we blame classroom teachers, the front-line responders to this fast-moving train wreck.

TISP does not solve this recursive compounded problem of public sentiment and the defunding of education. It does hypothesize that the root of system failure is not high ACE scores and dysregulated students, but the cumulative effects of unmitigated stress and trauma leading to individual and community dysregulation. As we have stated, our students’ and their parents’ difficulties are a mirror of shifts in cultural attitudes and relational behaviors happening on a larger societal level; student self-regulation challenges are logical given the seen and unseen chaos of our larger communities.

We have known that many worldview and behavioral trends are not beneficial to creating and sustaining safe and productive communities. But we could avoid responding due to the impact of these realities not interfering with us “too much.”

For many educators and parents, we are no longer acclimated and oblivious to the discomfort. As we have stated, our students’ and their parents’ difficulties are a mirror of shifts in cultural attitudes and relational behaviors happening on a larger societal level; student self-regulation challenges are logical given the seen and unseen chaos of our larger communities.We have reached a tipping point; the subjective levels of distress experienced by educators and students are painfully high and many districts are willing to do whatever it takes, the sentiment that fueled Geoffrey Canada’s work with the Harlem Children’s Zone (Tough, 2009). Your awareness of the level of distress many students experience, and how its cumulative and progressive impact on their neurological development impairs academic and social functioning, has armed you with concrete evidence of the hunches many of you have had all along.

After you take the post-survey, compare your results on Perceived Need and Urgency. We expect that for many already in the profession, your level of need and urgency was likely high at the outset, maybe changing a little in intensity. In fact, your already high level of awareness of a critical problem for many students today was likely a prompt to work through this material.

Educator Attitudes and Dispositions reflect a person’s internal motivation and willingness to change in response to trauma-informed insight. For some, the logic of a need is motivation enough. For others, the higher level of felt distress (urgency) summons a willingness to move mountains. This is the energy we see in school districts with high levels of distress, and it is the energy we see once educators begin absorbing the trauma-informed literature. However, if an educator is not willing or open to change, it can thwart an entire system’s effort, especially if that person exerts influence over others and a groupthink begins to take hold.

There are a myriad of factors that contribute to low motivation to change, even if the desired change makes sense. Perhaps most pronounced and valid is resisting change because what we are currently doing is working for us. Nothing creates resentment more than being pressured into change because it suits the agenda of those above you, especially when the wisdom is flawed from your vantage point. A second logical reason is lack of time and energy. For educators in all roles, the demands of the school environment are stressful; it is a job that is never done. For classroom teachers, it is a job with few boundaries around the work: you work most evenings and weekends, and spend your six to eight weeks of summer break picking up a second job and/or preparing for the next academic year. Unless they are teachers or live with one, few people understand the intensity of the school day and the added time demands outside of school hours. Add to this the emotional exhaustion and its cumulative effect, and many teachers cannot summon the time or mental energy to engage in the TISP learning process.

As highlighted in our review of burnout below, another factor undermining educator internal motivation may be resentment, if it feels as if your work environment has not treated you justly or been a wise steward of your district or school, in any combination or manifestation of leadership needed to build and maintain trust. Human systems, whether a family or a school district, are messy, imperfect communities that go through seasons of chaos and relative stability. The culture of your district, the invisible blueprint that we spoke of earlier that enables attitudes and patterns of behaviors to persist even as personnel change, is difficult to name or deal with at times; you are not imagining these things. And it does rip away at our motivation.

A final factor undermining motivation is our own burnout, a relative of compassion fatigue, which is primarily caused by repeated response to the trauma of others, a risk factor for educators we address further in this chapter. Burnout occurs for any number of reasons, including the following:

- We long for greater freedom in our daily lives; work, even work we enjoy, is something merely tolerated until we can retire.

- As stated above, we have felt used or taken advantage of, either relationally or economically in the work environment.

- We truly are in a profession that is a misfit for our talents and interests.

- The intensity of our work, including an unrealistic job description, exhausts our physical and emotional reserves.

- We are not taking frequent enough breaks from our work throughout the day, week, and seasons.

We imagine that you can add to this list and see a combination of issues contributing to your own moments or seasons of burnout.

Burnout is a significant factor impairing our health and well-being. In May 2019, the World Health Organization updated its classification of burnout in the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), listing it as an occupational phenomenon (not a health condition). WHO (2019) defines burnout as follows:

- Burnout is a syndrome resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterized by three dimensions:

- feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion;

- increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; and

- reduced professional efficacy.

- Burnout refers specifically to phenomena in the occupational context and should not be applied to describe experiences in other areas of life.

Notice that burnout does not impact other areas of our life when our work environment is the source of stress and other contributing factors are not impairing our health. The most significant sign of burnout is lack of work motivation, experienced as low physical energy and poor morale even in the face of positive change. We can’t “will” the interest or energy, as there is none to be had; our tanks are empty. The solutions to burnout are highly relative, depending on you and the factors contributing to it. The strategies we offer in response to compassion fatigue serve us well in responding to burnout; but ultimately, we must assess its meaning and make adjustments as we are able. In light of the fact that much burnout is due to poor working conditions, whether unrealistic job descriptions or toxic work cultures, WHO provides workplace guidelines to address issues that are often beyond the individual person’s ability to influence (WHO, 2019).

In your survey results, what are your Attitude and Disposition scores telling you? Do you see a connection between these scores and your Larger System Support scores? It is likely that most educators have fewer positive feelings about their jobs during high-stress seasons of the academic year, including that long stretch of time in the spring before school ends for the summer. Regardless of precipitating factors influencing your initial motivation score, many educators see a bump in their Educator Attitudes and Disposition scores because they see TISP as a ray of hope in a fairly bleak landscape. This is growth-producing energy we want to harness and protect, not exploit, as is captured in the two remaining factors. Regardless of precipitating factors influencing your initial motivation score, many educators see a bump in their Educator Attitudes and Disposition scores because they see TISP as a ray of hope in a fairly bleak landscape. This is growth-producing energy we want to harness and protect, not exploit, as is captured in the two remaining factors.

Educators displaying a low sense of urgency and high burnout are likely to be highly resistant to anything related to TISP; they may resent the push and negate its importance or their need to learn this new content domain. Here, we get to practice our Person of the Educator skills, responding with a consistent ethic of care as we apply TISP relational values in our relationships with each other. We saw Rachel model this in her reflection in Chapter 7. Here, we recognize the logic of this response, responding with empathy and respect (attunement) even as the system continues to move forward without shaming or shutting them out (mutuality).

Trauma-Informed Knowledge provides an internal conceptual framework that gives educators the language to describe what they already know, and to be able to trust that what they are experiencing requires new knowledge bases and skill sets. It intensifies Perceived Need and Urgency and increases Educator Attitudes and Dispositions. Compare your scores on Factors I, II, and III: As you are completing this course of study, if your knowledge base score has increased (Factor III), do you also see an increase in your Factor I and II scores? Successful and sustainable implementation of TISP does not require everyone to immediately be on board with a 100% level of commitment; energy grows over time, and exposure to the trauma-informed literature is a contributor to nurturing insight and commitment. It also becomes a primary tool for navigating moment-to-moment application of TISP, as strategies need to change on a dime, congruent with what a particular student or group of students is telling you through their verbal and nonverbal behaviors.

Larger System Support highlights the external constraints that make this work so tenuous and risky. This fourth factor can kill emerging motivation to change or allow its roots to deepen and strengthen over time. An Educator sold on TISP is stranded if the School’s administration is merely agreeable rather than an active participant and leader. A District will spin its wheels and waste good grant money and time if Educators are forced to participate without prior nurturing of interest. And Educators needing access to quality training may be led to believe something is trauma-informed when it is not, or is not truthfully presented. This factor alone can sink the ship at any point in time, and is why our Strategic Planning Teams need to be envisioned as multi-armed agencies whose work is measured (titrated) and sequenced over time.

What constraints did your initial survey results reveal, and what changes are you noticing on your post-survey? For some, this text may have sharpened your view of the potential barriers. Or your colleagues’ participation in this process may be giving you signs of hope that the external systems may be more reliable or accessible than you previously thought. And then there is your subjective sense of distress regarding the systemic limits of your setting. Envisioning these barriers as common, and knowing you have a team of trauma-informed educators, does affirm that a way around these constraints can most often be found.

Our fear is that TISP has all the earmarks of merely being experienced as a fad due to the typical confusion that inaugurates most shifts in established systems—a sense of quick training, immediate implementation, the expectation of great results that produces initial excitement and then crashes. We saw trauma-informed language being affixed to everything, from universities claiming trauma-informed educator coursework to pre-existing school discipline packages suddenly claiming to be trauma-informed. All of these observations are congruent with how systems proceed through change. Have you ever watched a disturbed ant colony? The frenzy of activity looks like mayhem. This is similar to what happens in our adolescent students’ brains— they are under major construction, and those neural circuits and the chemicals traveling along those pathways function as if in sheer chaos. But eventually the ant colonies and our neural transmitters sort themselves out if the conditions are optimized. And that is what we are seeking to do: provide a road map in the midst of natural and expected chaos to help steer the transition process into a calmer state of existence.

We urge you to use these four factors as a simple way to nurture interest and sustained efforts, especially as the survey will unearth educator motivation along with larger system constraints that could undermine our best hopes and intentions. This survey will be referred to again as we identify a full-range TISP evaluation process.

Re-Examining Our Research Questions: Data Collection and Analysis

Standard Outcome-Based Assessment Expectations

Assessing the efficacy of TISP is important to our work for all the typical reasons. First, Districts are being asked to invest time and financial resources into training and implementation processes. Vested stakeholders—such as grant and government funding sources, taxpayers, and each student’s parents—have a right to know if TI education methods are producing the desired results. Such data is crucial when seeking additional grant opportunities, often funding sources crucial to initial TISP implementation support. In addition, whenever we are building a new structure, much is unknown until we test out new skills and processes; course corrections are commonly needed along the way.

The most basic outcome measures seek improvement along the following indicators. The list also includes what we hypothesize to be the role of TISP contributing to these improvements:

- Increased daily student attendance rates. This would indicate an increased sense of belonging (Connecting) inspiring traditionally disenfranchised students to prefer school attendance.

- Increased academic success evidenced in grades and graduation rates. This would indicate that Coaching strategies helped academically struggling students increase access to executive functioning. Academic indicators may also show improvements because TISP Connecting and Coaching strategies increase the overall calmness of the classroom, minimizing episodes of class disruption.

- Decreased office referral and in-school detention/discipline rates. TISP hypothesizes that many episodes of student dysregulated behavior reflect internal need states a student does not understand, let alone know how to manage. Coaching processes, built upon a foundation of trust, help increase a student’s level of insight while also increasing self-regulation skills.

- Decreased expulsion rates. Students who commit an offense resulting in expulsion are often well known to school personnel long before the event precipitating school removal. The same processes decreasing in-school discipline rates apply here; we would have already reached out to these students, and in so doing, helped circumvent a behavioral spiral. In addition, TISP emphasizes the need to not force students into environments that are beyond their capacity to handle, even with the aid of educational assistants. We have an ethical responsibility to protect that student from repeated episodes of stress-induced dysregulation, as well as protect the emotional well-being of peers whose classroom experiences are often interrupted by students who cannot adequately respond to Coaching processes. As Districts examine their screening processes and classroom assistance options for students requiring greater assistance, classroom settings matching a student’s need would need to be more accessible. We understand that access to adequate resources is crucial, and not always possible. But TISP advocates that we never walk away from speaking up about the needs of students to be protected. In this case, all students suffer when we do not provide appropriate classroom settings for students who are in chronic states of dysregulation indicating they are in need of more skilled services.

This data is also useful to Schools and Educators as they evaluate their methods of implementing TISP. Less than desired outcomes invite Strategic Planning Teams and Educators to re-examine their Action Plans for gaps in their District, School, Educator, and Classroom implementation strategies. A common assessment process is examining discipline policies, specifically the direct and meta messages we are conveying in our methods. Likewise, examining the need for additional classroom assistance, or examining how teachers can better coordinate their Connecting and Coaching practices with students they share in common, also invites re-evaluation.

Typical data points, as listed above, will invite us to examine not just what we are doing, but how we are reasoning out our choices. Sometimes the needed changes are beyond our capacity, while in other instances, the wisest course of action is easily accessible. The next section walks educators through a process of evaluating TISP implementation progress to aid in our assessment of the level of influence of TISP on overall District and School outcomes.

TISP-Specific Assessment Needs

The nature of TISP asks educators to assess the efficacy of our efforts according to its basic premises. For example, each phase of the TISP Tri-Phasic Model invites us to design ways to assess student engagement with our processes. This is both to make course corrections and to affirm that your efforts are producing desired outcomes.

The method in which we collect TISP efficacy data differs from standard measures as well, which are primarily a School or District task. Assessing the day-to-day success of TISP varies according to one’s role. The primary challenge here is for classroom teachers, as it is difficult to discern data-gathering methods that are quick and effective given the limits of time and the volume of students under their care. But persons in all roles will benefit from engaging in this same process of assessing student engagement in TISP processes.

The following details a process to assess the veracity of TISP implementation efforts. It begins with an assessment of School and Educator TISP engagement and practice, followed by strategies for identifying signs of student engagement in TISP activities. The TISP evaluation process is not directly focused on learning outcomes, as the basic premise is that engagement in TISP Schools and Classrooms enables a student to access executive functioning required for academic engagement. The data you collect here is designed to help monitor accurate application over a long enough time across multiple grade levels; the results can then be compared to standard school outcome measures, including academic progress.

Assessing TISP Stage of Development. Reliable and valid TISP evaluation requires a School and its Educators to first develop TISP competencies and implement changes in the culture of the school, evidenced in daily routines, rituals, and practices throughout the school system. Assessing the stage of development includes examining the following:

- Accurate application in ethos and practice

- Implementationof TISP in multiple systems within the school

- Implementation of TISP in multiple successive grades

When evaluating the effectiveness of TISP in helping schools achieve desired outcomes for students, you need a realistic picture regarding pockets of the school day and the school progression process where students are or are not experiencing consistency in TISP ethos and practice. The gaps in TISP implementation are helpful clues to understanding less than desired TISP-related student engagement data, as well as marginal changes in overall district and school outcome data. Assessing the developmental stage of TISP implementation also helps you distinguish expected developmental processes yet to unfold from areas where adjustments need to be made in current implementation strategies and practices.

At the conclusion of this section, we provide a detailed exercise in which we invite you to assess your stage of TISP development at the District, School, and Educator levels. Collaborate on the exercise with others working through this textbook, or with coworkers also implementing TISP.

Assessing Student TISP Engagement

In Chapter 7, we invited you to place on your radar the importance of capturing data regarding student engagement with TISP culture and practices. It included watching for the following behavioral indicators:

- Student attitudes displayed in classroom atmosphere

- Behavioral challenges in frequency and intensity

- Student response to your interventions when having behavioral challenges

- Student use of self-regulation resources and techniques

- Your sense of efficacy when dealing with challenging encounters

- Student engagement in the rituals and other learning moments

- Student feedback on how they felt heard or tended to during a difficult encounter

Basically, we are seeking to identify how a student is responding to our efforts to promote an emotionally and physically safe environment where they are seen and valued, and have their own acts of care and concern valued as well. (Yes, when we give another person the gift of kindness, it promotes feelings of safety, well-being, purpose, and worth, reinforcing that we matter and can make a difference.)

Next, we are looking for signs that a student is incorporating the lessons they are learning about how the brain functions; how to tune into the thoughts, feelings, and sensations rippling through their bodies; and how to calm their circuitry long enough to respond to these inner need states with more clarity and intentionality. This is a lifelong course of study and practice, but we are building these skills one moment, one activity, one season at a time. What might be signs that the student is absorbing your social-emotional tutorials and practice strategies? Are they using the skills, and what is the impact?

And finally, we are looking to see how these individual responses are reverberating throughout the group, and what kind of community energy is emerging. Empathy is recursive: the more we receive care from others, the more we can understand our own internal processes, and the more we can then show that same level of empathy for others. Empathy and responsibility go together. Initially, we act responsibly because we are told to do so, and we may fear some negative consequence or the loss of a positive reward if we do not comply. These are the characteristics of the law-and-order stage of moral development (Kraus, 2009; Wikipedia Contributors, 2018). But responsible action ultimately requires insight and compassion toward self and others, so when we are expected to put aside our own needs in the moment, we understand why and have the inner confidence that we are anchored and internally “OK” as we respond to the relational demands of the environment. This is a Phase III task in which we nurture community relationships reflecting the cumulative and transformative effects of Connecting and Coaching growth processes.

You are likely already observing signs of student engagement with TISP. As you collate your observations, here are a few preliminary considerations to help give shape to your data collecting processes:

- What do you want to know, and how might you design a simple method of charting your observations?

- What students are most challenged by the academic environment, and how might you and other classroom teachers or school staff brainstorm together on methods of tracking the engagement of these students in a more detailed manner?

- How might you invite students to give direct feedback? Students are partners with you in this process; the more they know why the class engages in these activities and can help create these processes, the more invested they become in participating, benefiting, and evaluating the impact.

- Once you identify a variety of methods suitable to your TISP engagement and learning goals, how might you design checklists, surveys, and other data collecting methods that are co-created by your peers who may also be able to use these same tools? This begins allowing your school to collect hard data for presentation to your administrators, school board, and professional educator conferences and publications.

Next, identify the purpose and goals of each phase of TISP implementation. For a review of trauma-informed tri-phasic concepts and response rationale, revisit Chapter 5. Then re-examine each phase of the TISP Tri-Phasic Model, as detailed in Chapter 6, to assist in this process.

- Phase I: Connecting: Are students enjoying the rituals and routines you implemented to create a sense of emotional connectedness and safety? How might you document direct signs of student engagement? How might you document signs of discomfort, boredom, or disinterest? For those uninterested or not engaged, what might be your hunch as to why? What are you noticing in the student when you practice more overt attunement, focusing on hearing their experience first before rushing to a solution?

- Phase II: Coaching: Here you are looking for signs that students are eager to learn about their inner need states and respond with situation-appropriate strategies (whether in a classroom or a cafeteria setting). Are students using the self-assessment and regulation tools you have taught and provided? If they are not using the tools, are you asking too much too soon, or without proper instruction and structure? Or, are they ready to engage more deeply and bored with the current offerings?

- Phase III: Commencing: Here you are looking for signs that your students are self-initiating the use of skills taught, and easily work with you when they have moments of intense dysregulation. Remember, while our goal is to reduce episodes of dysregulation, your students need to encounter intense inner need states in order to practice skills. A student who has become angry and disruptive but then allows you to connect and coach them into a more relaxed state is showing progress. How might you document such instances? This phase is also asking you to assess when a student is not capable of scaffolding additional skills needed to increase their abilities to self-regulate.

Deepening TISP Perceptual and Conceptual Skills Through Group Observations

When we provide TISP peer observations and coaching, each educator presents a case study of an element of TISP that is not working as hoped or is difficult to implement, along with a video clip of the situation under review. During one such TISP coaching session, two classroom teachers from different schools presented a similar difficulty, chronicling less than successful results with a particular social-emotional self-regulation strategy. As the peer consult process unfolded, each teacher discerned two totally different sources of the intervention strategy’s ineffectiveness.

One teacher was able to identify their student’s need for more novelty, changing up the activity now and then. They were operating under the principle that predictability—often meaning sameness—helped produce safety and engagement. What the teacher did not expect was to see signs of growth in their students at such a rapid pace, and the corresponding need for change. The discovery added an exciting depth to the teacher’s conceptual framework, learning how to identify student growth and the need for the next level of skills in social-emotional learning processes to further increase neural network integration.

The other educator observed student willingness to engage, but the needs of some students with more limits in their capacity to self-regulate indicated that the teacher needed more adult assistance in the classroom. The teacher was reluctant to trust their assessment of such need, instead assuming that they were not implementing TISP strategies in a good-enough manner. The peer coaching and consultation process, a form of self-assessment, helped each member of the group deepen their TISP skills and make unique course corrections based on the application of TISP concepts.

Assessing Student Engagement with TISP Practices

As you begin to implement TISP into your practice and classroom, it is important to regularly assess those changes to see if they are working in the way you hoped. In Chapter 9, we shared the Problem-Solving Mat strategy that Sky and her cooperating teacher implemented in the classroom. They assessed this strategy and learned they needed to make a couple of tweaks. Here is what they found:

We watched our students use the mat and assumed that things were working well, but we wanted to get input from the students. We decided to create a questionnaire for the children about the problem-solving mat. It had two sentence frames where the kids had to choose “The problem-solving mat works for me because . . .” or “The problem-solving mat does NOT work for me because . . .”

They then had to circle their feeling responses when using the mat:

-

- Happy because they solved the problem on their own;

- Content because their problem was fixed;

- Angry because their problem was not solved and they were still angry; or

- Frustrated because they still had a problem.

Then the last question was “What is something that we can do to make the problem-solving mat better?”

All 27 students filled out this questionnaire; 23 students said they were happy with how the problem-solving mat was going. For the four that did not feel like their problems were being solved, we realized these students were bringing problems much too large to the problem-solving mat or were not using the mat exercise appropriately.

This gave us good information on how to help those students. Some of their concerns and suggestions included:

-

- We should require that a student helper is available every time the mat is used;

- Everyone should be trained on how to be a helper;

- We should add a step to our instructions that includes saying “I heard you say . . .” after the student states their problem.

We then made those changes. A few weeks later, we checked in again with our students. We found that 26 of the 27 students said they were feeling good about the problem-solving mat and thought it is working well. The one child who still struggled with the mat exercise was new to the class and did not yet feel comfortable asking other kids to the mat when he had an issue.

Since introducing the problem-solving mat, we have noticed a dramatic change in the number of students who tattle on each other. The children are learning that communication is key to building a classroom community, and they are able to actively learn how to communicate about their issues and solve them. —Sky, Student Teacher

You will see signs of TISP student engagement every day; it is just a matter of designing a method to document those observations. Whether you use an Action Research outline, checklists, peer supervision and consult processes, a daily journal, or sticky notes stuffed in a drawer, use your emerging perceptual and conceptual skills to make sense of what you are seeing and how students are engaging with you and their peers. Sometimes your observations will tell you something is missing. But many times a student’s response will melt your heart; chart it and allow yourself to celebrate the resilience of the human spirit when provided just a little bit of safety and stabilization. Other times your results will tell you that your students are responding just as you hoped and are now ready for something deeper, something more. Chart it, use your TISP competencies to go that next mile, and enjoy the ride!

Chapter 12: Exercise 1

Assessing Stage of TISP Development

The desired outcomes of TISP are to increase student engagement and learning in academic and social competencies; TISP is deemed effective by these measures. But to properly discern the effect TISP has on these desired outcomes, its stage of development must be determined. We identify its development by examining the strength of TISP implementation, determined by assessing its accuracy (true to TISP knowledge, skills, and dispositions), and breadth of implementation within the school the student is attending (not just in a particular classroom), and in previous and successive grades.

A school or classroom may state that it is applying TISP when in fact school personnel are not familiar with TISP foundational principles. TISP practices may be inconsistently applied, yet this inconsistency might be logical given its stage of development within a school or district. In both of these instances, we cannot make strong assumptions regarding how TISP practices are affecting attendance rates, academic functioning, or discipline statistics until we have TISP accurately and firmly in practice.

Elements of the TISP stage of development are discerned using the following levels of assessment:

- Stage of development for Districts, Schools, and Educators

- Attitudes and dispositions of administrators and staff

- Student engagement with TISP school and classroom practices

All levels of assessment offer formative (each system element’s grasping what it needs to move onto the next phase) and summative (signs of reaching the final desired outcomes) data useful for identifying next steps in the strengthening and efficacy of TISP. The profile that emerges from this review of TISP stage of development allows the educator to openly and realistically assess TISP maturity, strengths, gaps in services, and other areas of concern. This information is then used in the interpretation of overall outcome measures gathered and analyzed by district personnel.

Assessing Stage of Development

If your school or district is actively engaged in transitioning to TISP, using the stage categories below, confer with your colleagues to begin gathering data useful to charting TISP stage of implementation. Remember, transition processes are unstable and unpredictable. Less than desired outcomes during the early and middle stages of implementation may reflect various gaps in service that are waiting their turn for development. Despite less than optimum results, gains will be observed. In addition, as the educator understands foundational trauma-informed concepts, and continues to participate in their own TISP training and supervision, collecting TISP data throughout the process will easily identify needed course corrections that make conceptual sense to staff and administrators.

Early in this section, we identified strategies for assessing student engagement with TISP school and classroom practices. Attitudes and dispositions of administrators and staff are assessed in the Predictors of Successful and Sustainable TISP Implementation survey. This exercise is designed to merely assess the stage of TISP implementation. At the end of this exercise, you will be able to complete a TISP assessment process and juxtapose the findings against your school or district’s outcome data relative to your inquiry.

Identify Overall Stage of Development. Begin your assessment by identifying overall stages of TISP development for your district, your school, and yourself. You will use these same categories to assess the specific elements of each education system (District, School, and Educator) in the next step. Student TISP engagement (Classrooms) is evaluated separately, as described earlier in this chapter.

As an educator gains TISP competencies, their application becomes more nuanced and effective. Likewise, TISP needs to be consistently and continually applied in a school and its classrooms, giving students ample time to absorb its effects, as they are learning to trust the environment, absorb new community and self-regulation habits, and practice them. It is similar to expecting a nutritional or health practice to have the desired effect immediately, versus understanding that habitual exposure to a new routine builds new infrastructures over time that manifest in full recovery some time down the road. Also, note that the categories do not speak to the internal mindsets of various educators; these can be hypothesized by utilizing the Predictors of Successful and Sustainable TISP Implementation survey.

Below are six stages of TISP engagement and practice reflecting overall TISP interest, commitment, or sustained action. Rough time periods to accomplish implementation tasks are offered as a guideline, not an absolute. Place a “D” next to the stage reflecting your assessment of your District’s engagement with TISP; place an “S” next to the stage reflecting your School’s implementation; and place an “E” next to the stage reflecting your personal (Educator) level of activity engaging with TISP.

- Precontemplation Stage: My district, school, or I have not yet expressed interest in TISP.

- Contemplation Stage: My district, school, or I am actively discussing implementing TISP.

- Early Stage Commitment: My district, school, or I have committed initial resources to training administrators and staff (whether a small cohort or a large group) in TISP and its application with students; often occurs within 0-12 months.

- Initial Application Stage: My district, school, or I am actively engaged in implementing TISP in schools and classrooms; often occurs within 0 months-2 years.

- Intermediate Application Stage: My district, school, or I am deep into the TISP implementation process, no longer novices but not yet widely used. Elements of a school are still in the process of training staff and/or adjusting various subsystems serving students; often occurs within 2-3 years.

- Longer-Term Application Stage: My district, school, or I have made significant gains orienting staff and adjusting school and classroom rituals, routines, and practices. Systems within schools have been reevaluated, and necessary adjustments have been made; all staff has access to initial training as well as access to resources for advanced training; often occurs within 2-5 years.

Identify Specific TISP Engagement and Practices. Using the six-stage identification system introduced above, assess the stage of TISP development for each specific item where requested. Place the stage number to the left of each item.

- Identify stage of District engagement:

- District Strategic Planning Team: Is it in place and active?

- District Engagement with TISP Foundational Knowledge: Are district-level administrators engaging in learning trauma-informed content domains and their application to school environments?

- Identify stage of School engagement:

- School Strategic Planning Team: Is it in place and active?

- School Engagement with TISP Foundational Knowledge: Are school-level administrators engaging in learning trauma-informed content domains and their application to school environments?

- TISP Basic Phase I and Phase II Skill-Development Training: Are school administrators participating in skill-development training, including direct observation of TISP rituals, routines, and practices within the school and classroom setting?

- TISP-Focused Group Coaching and Supervision: Are school administrators participating in TISP coaching and supervision processes to monitor their application of TISP and to deepen their student assessment skills? This process invites administrators to secure a TISP-trained coach, trainer, or supervisor who facilitates group supervision processes whereby administrators (along with their staff) present details of their application methods. Focus in on applying conceptual skills to evaluate efficacy of an activity or method as well as discerning student readiness for next stages of Coaching and Commencing activities.

- TISP Advanced Phase II Skill-Development Training: Do administrators and staff have access to, and participate in, advanced social-emotional (neural integration) skill development?

- Identify stage of Educator engagement:

- Educator Action Plan: Is it in place and active?

- Educator Engagement with TISP Foundational Knowledge: Are you as an Educator engaged in learning trauma-informed content domains and their application to school environments?

- Are peers serving the same students also learning and applying TISP?

- Are teacher cohorts collaborating in observations and methods?

- Are your students gaining access to TISP in previous grades within your district? In other words, how familiar might your students be with a trauma-informed school environment prior to entering your classroom?

- If your students have experienced a trauma-informed environment prior to their current grade level, did the District provide a way for the Schools to arrange for consultation between the grade levels as part of the process of ensuring continuity?

- TISP Basic Phase I and Phase II Skill-Development Training: Are Educators participating in skill-development training including direct observation of TISP rituals, routines, and practices within TISP schools and classrooms, accompanied by specific examples of strategies as initial toolbox ideas?

- TISP-Focused Group Coaching and Supervision: Are Educators participating in TISP coaching and supervision processes to monitor their application of TISP and to deepen their TISP assessment skills? This process invites educators to secure a TISP-trained coach, trainer, or supervisor who facilitates group supervision processes whereby educators (along with administrators) present details of their application methods. Focus in on applying conceptual skills to evaluate efficacy of an activity or method as well as discerning student readiness for next stages of Coaching and Commencing activities.

- TISP Advanced Phase II Skill-Development Training: Do classroom teachers and other staff and administrators have access to, and participate in, advanced social-emotional (neural integration) skill development?

Summarize and Incorporate Two Additional Data Sets

- Data gathered from the Predictors of Successful and Sustainable TISP Implementation survey: Use survey results to further your insight when comparing all assessment results. These results also specifically assess educator attitude and dispositions toward the use of TISP.

- Data gathered from assessing student engagement with TISP routines, rituals, and practices.

Hopefully you have been conferring with classmates or colleagues in the completion of this exercise. At the conclusion of your review, discuss your findings by reflecting on the following questions:

- What data was the most difficult to gather? What method(s) did you design?

- What surprised you the most?

- What was most encouraging?

- What was most disappointing?

- Create a list of 10 action items you, your school, or your district (not 10 per system level, just 10 total) would be advised to consider in light of your results. Identify one top-priority item for each system level. Using your TISP conceptual skills, discuss your reasoning for your top-priority items.

- If you are a practicing educator and applied this exercise to your school or district, based on this assessment process, do you think TISP is accurately and adequately implemented to such a degree that you can begin determining its influence on desired student outcomes?

Person of the Educator: Preventing Compassion Fatigue and Burnout

An Administrator’s Insight on Teacher Retention

Many districts are struggling to recruit and retain teachers right now. Although being a teacher is incredibly rewarding, it is also demanding and stressful. Unfortunately, many young, talented teachers choose to leave the profession due to the daily stress of teaching highly challenging students, most of whom have been (and continue to be) impacted by trauma. Equipping staff with effective TISP strategies, establishing a caring, consistent school culture, and combining resources with community partners are great ways to support teachers and help them be able to focus on instruction.

—Bruce, District Office Administrator

The Realities of Burnout and Compassion Fatigue

Throughout this text, we have provided opportunities for you to tend to the Person of the Educator by engaging in reflections and exercises. Our goal was to remind all of us that trauma-informed practice requires a consistent ethic of care, expressed in the way we relate to each other in the workplace, that honors educators as professionals. This requires us to acknowledge that we are vulnerable not just to the impact of our own unmitigated stress and trauma, but to secondary trauma as a result of working with the pain and resulting chaos of our students who bring their unmitigated stress and trauma to us each day, beseeching us for help.

We end our time together by taking a quick dive into the personal risks of being an educator as a reminder that trauma-informed awareness and practice is not just something we implement in our schools, but deserves to permeate all of who we are. This specialty is all about providing insight and concrete ideas on how to care for self and others regardless of the social and relational forces that seek to undermine our quality of life.

Burnout: Compassion Fatigue’s Twin

Earlier in this chapter, we identified some of the traits of burnout, including its many causes. Below we will explore compassion fatigue, along with ways to respond. The primary difference between the two is very slight. Imagine you are climbing a mountain, as we are doing when transferring our school practices to a TISP model. We can lose motivation and become truly exhausted with the process. This is not because we are battered and bruised by the dangers, or saddened by things along the way; it is because we are simply exhausted, and we need a break or a change of scenery. This is burnout. We need renewal in one form or another. Compassion fatigue and burnout often co-occur, but not all thoughts, feelings, and sensations of burnout are compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue is primarily activated when our empathy circuits are in constant attunement with the pain and suffering of others we serve; it may require a similar self-care response, but it is qualitatively different than burnout, as we will unpack below. To that end, as you are engaging in your own self-assessment, we want to acknowledge this difference.

Identifying and Responding to Compassion Fatigue

When we began initially exploring trauma in educational settings, we found a need to learn each other’s languages. Specifically, the mental health field has conceptual language and names for things not historically used in education. On one particular occasion a few years ago, I (Brenda) was sitting in Anna’s office and shared that teachers were exhausted and emotionally drained, and many were leaving the profession. As I described for her what I meant by this, Anna immediately identified this as compassion fatigue. Thankfully, over the last few years, this language has begun to seep into the education field.

What I described mirrored what Figley (1995) reported. He found that therapists and other professionals talked about “episodes of sadness and depression, sleeplessness, general anxiety, and other forms of suffering that they eventually link to trauma work” (Figley, 1995, p. 2). He went on to point out that “professionals who listen to clients’ stories of fear, pain, and suffering may feel similar fear, pain, and suffering because they care. Sometimes we feel we are losing our sense of self to the clients we serve” (p. 1). When we are exposed to others’ unmitigated stress and trauma, it can be an activating event for us, causing us to recall our own painful memories.

In 2012, Borntrager et al. designed a study to explore compassion fatigue in the education profession. This was the first study to consider secondary traumatic stress in the lives of teachers. They found that public school teachers and other educational professionals may very well be exposed to what they described as “extraordinary levels of direct and secondary trauma” (p. 48). They also found that few supports existed within the school network, which could result in an overtaxing of personal support networks.

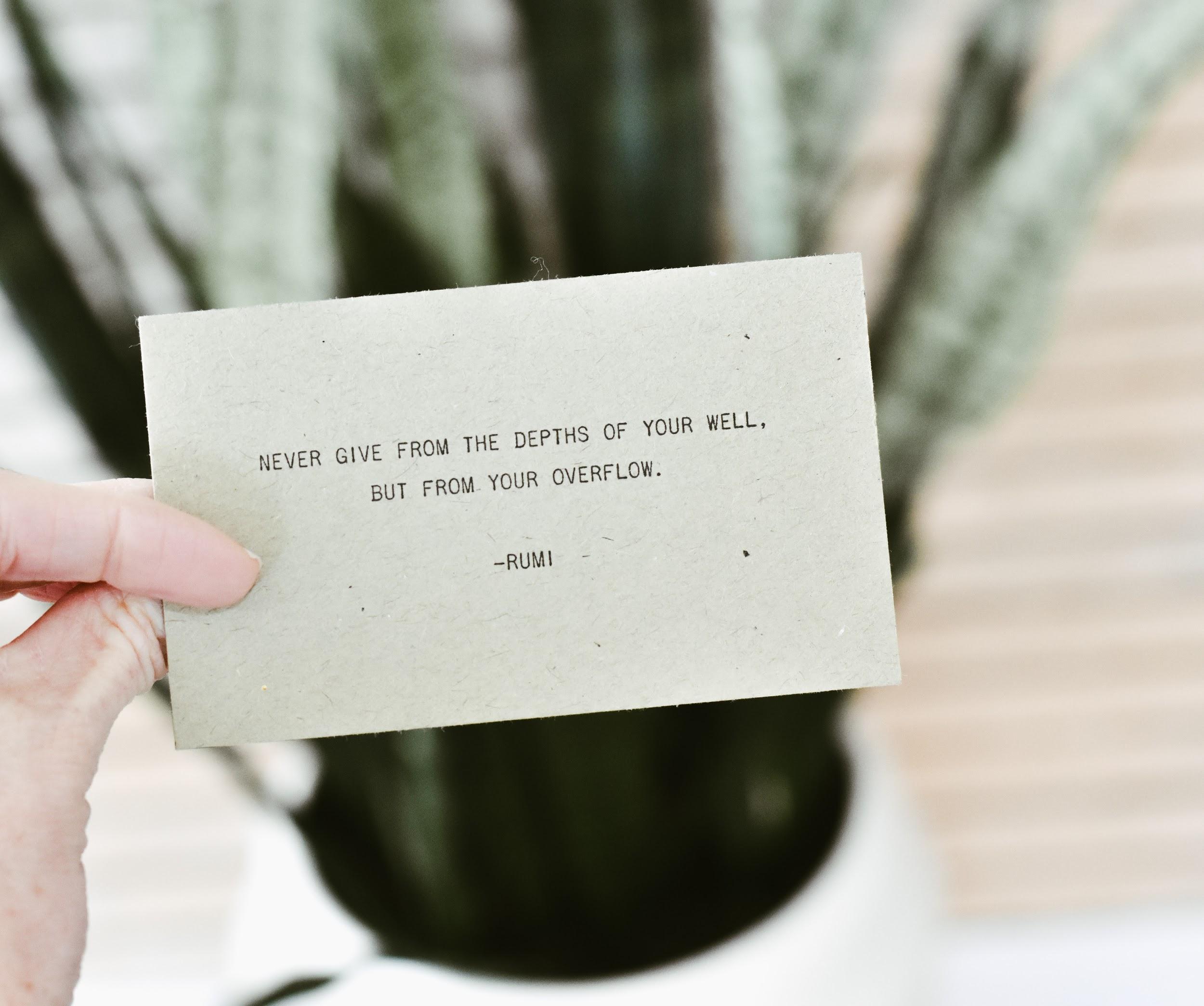

Teachers’ plates are beyond full. There are always papers to grade, lessons to write, and pressure to get our students successfully through standardized exams; the list goes on and on. Many teachers describe feeling guilty when they take a night off mid-week or enjoy a weekend, believing that their time should have been spent planning or grading. Nevertheless, this is a mindset that must shift. We absolutely cannot care for others when we have nothing more to give! There are always papers to grade, lessons to write, and pressure to get our students successfully through standardized exams; the list goes on and on. Many teachers describe feeling guilty when they take a night off mid-week or enjoy a weekend, believing that their time should have been spent planning or grading. Nevertheless, this is a mindset that must shift. We absolutely cannot care for others when we have nothing more to give! And, if we are being honest, we would also admit that when we are exhausted, our teaching is less than our best. Let’s begin to change that mindset.

First, we encourage you to assess your compassion satisfaction, fatigue, and burnout in the 30-question survey linked in the exercise below.

Chapter 12: Exercise 2

Assessing Your Compassion Satisfaction, Fatigue, and Burnout

The Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL R-IV) is a 30-question survey that allows you to self-assess the impact of unmitigated stress and trauma on your life. You can access the ProQOL R-IV at http://www.proqol.org. Once you have completed the self-assessment and scoring, take a moment to record your scores:

Compassion Satisfaction Score ________

Compassion Fatigue Score ________

Burnout Score ________

You may find that your scores fluctuate depending on the time of year you choose to take the self-assessment. As teachers, we tend to have lower scores in the fall, versus at the end of spring.

Now that you have completed the survey, are you surprised by your compassion fatigue score? Whether your score is sounding alarm bells that changes are desperately needed, or your score shows you are doing OK at the moment, a self-care plan will support you throughout the year. There is no time like the present to commit to making changes. You are worth scheduling self-care! Your students, school community, and friends and family will thank you.

I (Brenda) have a group of friends that I regularly write with. We meet weekly, away from our university campus, where we can enjoy coffee together, catch up, reaffirm our writing and research goals, ask for support, and then write. It is a simple formula that has carried us through three years. There have been weeks when one of us has felt too busy to enjoy the luxury of writing; after all, we had papers to grade and students who were scheduled to meet with us! However, we kept those dates and never regretted a moment. In fact, we usually end our sessions with hugs and words of gratitude. Meeting regularly and writing are on the self-care plan for all three of us. What should be on your self-care plan?

A self-care plan is both preventative and your “go-to” in the midst of a crisis. We encourage you to complete the exercise below and create your own self-care plan.

Chapter 12: Exercise 3

Self-Care Plan

A quick Google or Pinterest search will yield a number of websites dedicated to developing a self-care plan. Whether you create your own layout in a bullet journal or desire pre-made worksheets you can download, you will find endless processes and categories. For now, let’s focus on five topic areas. Grab a piece of paper and let’s begin.

Make a list of things, experiences, or situations that give you joy and leave you feeling recharged or rested for each of the following categories:

- Work

- Relationships

- Emotional well-being

- Physical well-being

- Spiritual well-being

Now that you have a list, begin to think about things that could keep you from enjoying that activity or experience. What do you need to do to keep those things from impeding your ability to carry out your plan? What support do you need from others to stick to your plan?

Begin to schedule items from your list into your calendar. Perhaps pick one activity and plan to engage in that activity each week or every other week. Or, choose one activity or experience each month and stick to it.

Once you create your self-care plan, we encourage you to regularly assess how it is working for you. One way is to retake the ProQOL R-IV assessment periodically to see where you score. Another is to self-assess your own mental and physical health. Are you noticing a change?

What might you do if you develop a wonderful plan, even act on a few of its elements, and still notice no change in your subjective sense of compassion fatigue or burnout? It is common for us to decide to “just do it,” only to find we don’t engage in the plan, or it doesn’t create the shift we were hoping for. Here is a moment to practice with yourself exactly what you are or will be practicing with your students: Trust that there is a reason worth discovering that is leading to your avoidance. Compassion fatigue and burnout affect each of us in unique ways. For some, a detailed plan works; for others, being with close trusted others is comforting, leading to a kickstart in our motivation. And for many, just giving our brains and bodies a change of view helps access our desired goals and reservoirs of well-being, which then helps us metabolize an inspiring read or galvanize energy to move on an action plan. Listen to your resistance. Whether it is helping you identify a deeply held perspective, as we discussed in Chapter 2, or giving you greater depth of understanding regarding the source of the problem and the need for another solution, it is all good!

A Final Thought

It is fitting that we close our text with a look into the realities of burnout and compassion fatigue, as we acknowledge once again that unmitigated stress and trauma stem from complex ecosystemic forces. We are reminded that the struggles of our students are a sign of something gone awry in our relational patterns that has affected our students’ parents, and likely their ancestors as well. Unmitigated stress and trauma change our biology; they affect our thoughts, feelings, and actions. The ways we interact in the world not only reflect what we and our ancestors experienced, but are mirrored in cultural values and trends, so much so that we think good things are bad and bad things are good. Bronfenbrenner’s diagram (Figure 10.1) depicts the nested, interrelated set of systemic forces that shape our identities and our emotional health. It remains a powerful reminder to not be so quick to blame parents, to zoom out so we can acknowledge the bigger picture, and then zoom back in to identify the power we do have to heal and increase resilience in spite of larger social obstacles.

We have stressed how we are no different from our students and their families; we are all impacted by the slings and arrows of life, whether from relational injuries that have occurred in our own families or broader cultural forces that undermine our sense of self, safety, and belonging. We have also emphasized the universal-access nature of TISP; what a trauma-informed environment offers is what all of us need to nurture a firm integrated sense of self so we can muster the courage to engage in the challenges of life, managing our own responsibilities within communities of care who help along the way. What we offer our students, we need as well. We challenge our students to strengthen their internal neural networks, and we, likewise, are engaged in that process throughout our lifespan.

Given that you too are impacted by unmitigated stress and trauma, be sure to place on that self-care action plan a method of acknowledging and holding with compassion your own life history. These are trails that lead to deeply held perspectives that influence maybe what you choose to do, but certainly the mindset you use in doing what you do, primary contributors to burnout and compassion fatigue. Basically, it is our own internal neural networks knocking on our door saying, “Please read what’s up and take me to the next level of integrated neural network functioning!”

Whether this means processing with a friend or a therapist, know that any route you choose is exciting. A topic both of us have visited on occasion is the way psychotherapists view therapy. For many, counseling/therapy is a professional treatment service we access when something in our life is not going well and we need help sorting it out. For others, not just therapists, it is as nurturing as getting a massage or a pedicure, and as exciting as setting out on a traveling adventure. It is the ultimate in deep learning and personal challenge, leading to a greater sense of inner peace and life energy. While owning my own bias, I (Anna) invite you to expand your understanding of therapy as a self-care option, not just a tool to access in times of great distress.

However you embark on applying TISP to your own professional and personal growth, we hope that you leave our time together with conceptual language to make sense of what you have likely known for a long time. We hope that despite the sadness or heaviness these realities create—especially if your empathic attunement neurons are working—you are comforted in knowing that others see this too, and perhaps the best way to muster hope is to be a part of the solution. As you work to strengthen your own application of TISP in whatever role you occupy within the school system, rest assured that you are not alone, and that what you do matters and is what is needed most. We do not have any control over whether a student can respond as we hope, but never underestimate that you are touching deep neural networks when you attune and respond to your students. You may not see the impact today or this year, but you are planting seeds of hope as students learn they are seen, cared about, and able to bring their own unique goodness and beauty to our lives and our communities.

Resources for Further Reading

- The Compassion Fatigue Workbook: Creative Tools for Transforming Compassion Fatigue and Vicarious Traumatization, by Francoise Mathieu.

- Onward: Cultivating Emotional Resilience in Educators, by Elena Aguilar.

- Trauma Stewardship: An Everyday Guide to Caring for Self While Caring for Others, by Laura van Dernoot Lipsky with Connie Burk.

- Mindful.org. This organization provides information and suggestions for developing your own mindful practice.