6

“Learning is not attained by chance, it must be sought for with ardor and attended to with diligence.” ―Abigail Adams

“Safety and security don’t just happen, they are the result of collective consensus and public investment. We owe our children, the most vulnerable citizens in our society, a life free of violence and fear.” —Nelson Mandela, Former President of South Africa

Desired Outcomes

This chapter consists of a single document: The (TISP) Tri-Phasic Model, preceded by an expanded description of the document’s elements. It provides a metaframe for academic institutions preparing educators to develop trauma-informed educator competencies, and for districts and schools transitioning to Trauma-Informed School Practices. This document, along with the remaining chapters in this text, will enable educators to do the following:

- Guide academic environments, including districts and schools, in the transition to trauma-informed school practice, including strategic planning processes required for successful implementation

- Provide a structure in which to evaluate appropriate training resources and programs claiming to be trauma-informed

- Advise higher education teacher preparation and educator certification programs in securing qualified faculty to develop trauma-informed educator curriculums and provide instruction for those courses or units

- Inform mental health training curriculums preparing practitioners to serve in school environments as verified trauma-informed providers

Key Concepts

This chapter contains the Trauma-Informed School Practices (TISP) Tri-Phasic Model educator competencies. It is preceded by an expanded description of the document’s elements. Key concepts defined include the following:

- The TISP Tri-Phasic Model description and goal

- The four guiding principles of TISP

- The identification of prominent pre-existing trauma-informed response models corresponding to the TISP Tri-Phasic Model

- The TISP Tri-Phasic Model as an education system’s change model

- Trauma-informed competencies organized according to an integrated model of educator skill development

Chapter Overview

In the preceding chapters, we unpacked an overview of the severity of need for schools to re-evaluate how to respond to the academic and social-behavioral challenges of students exacerbated by unmitigated stress and trauma, impairing readiness to learn. We then provided an overview of trauma-informed concepts detailing the nature of trauma, factors that contribute to risk and resilience, and an overview of best-practice strategies underlying all ends of the trauma-informed care spectrum.

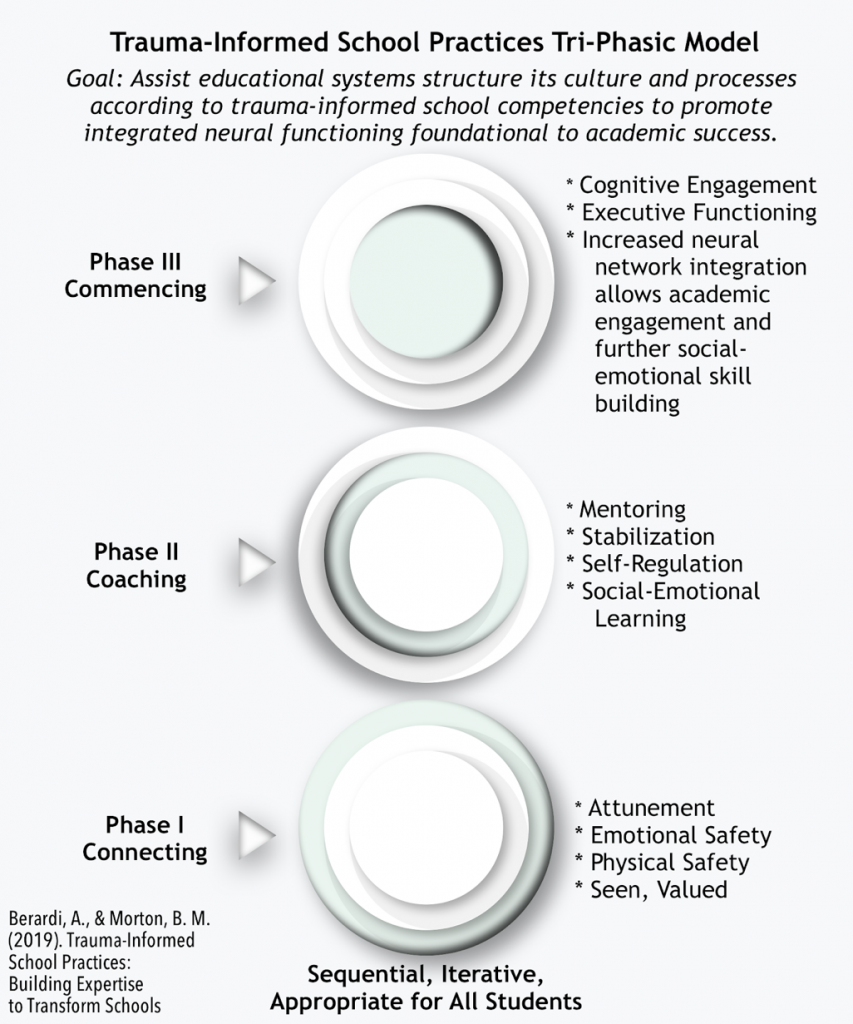

We end Section I with a summary of the Trauma-Informed School Practices Tri-Phasic Model, a metaframe representing a coalescing of trauma-informed concepts as applied to the education environment. Refer back to this summary in the remaining sections of this text, as it is the guiding blueprint for each element and stage of implementation and evaluation.

As we prepare to unpack specific trauma-informed educator competencies, we begin with an overview of the TISP Tri-Phasic Model. Its purpose and goals are detailed, as well as conceptual elements informing the model. It reinforces that implementation is multi-layered, with all aspects of planning and implementation needing to be embedded in trauma-informed knowledge, skills, and dispositions that inform educator perceptual, conceptual, executive, and professional skills.

We then detail trauma-informed educator competencies within the TISP Tri-Phasic Model. This model is grounded in trauma-informed concepts, best practices in response to increasing wellness and recovery from stress and trauma, and the authors’ knowledge and expertise in the application of trauma-informed knowledge, skills, and dispositions to the educational setting (Berardi & Morton, 2017; Morton, 2018; Morton & Berardi, 2017, 2018). Conceptual domains include an integration of traumatology, neurobiology, and developmental theories as it relates to optimum development and the impact of unmitigated stress and trauma on development.

The Trauma-Informed School Practices Tri-Phasic Model

Description

The Trauma-Informed School Practices Tri-Phasic Model is a metaframe for developing educator competencies required to safely and effectively implement trauma-informed school practices. It is a universal-access approach to learning for use by teacher preparation and educator credentialing programs, mental health professionals working within educational settings, and districts, schools, and staff transitioning to trauma-informed practices. TISP also applies to higher education, both undergraduate and graduate settings. The model details the knowledge, skills, and dispositions congruent with trauma-informed educator expertise. It is based upon trauma-informed research integrating advancements in the neurobiology of stress and trauma, developmental theories, and best practices regarding how to help persons recover and resume development. This text emphasizes the application of these competencies within K-12 school systems, in individual classrooms, and in service to the Person of the Educator.

This phase model is both sequential and iterative. While each phase scaffolds a student’s ability to engage in the tasks of successive stages, students and the school environment are continually looping back around, cycling through each phase in both small, immediate cycles on some elements and large, long-term cycles for other elements.

Goal

The goal of TISP is to assist all elements of an academic environment in structuring its culture and processes according to trauma-informed school competencies to promote a student’s integrated neural functioning, which is foundational to academic success. Trauma-Informed School Practices recognize that developmental, social, and cultural pressures, in addition to unmitigated stress and trauma, disrupt the formation and integration of neural networks foundational to social, emotional, and cognitive developmental processes, impairing a student’s ability to be successful in academic environments. The goal of TISP is to assist all elements of an academic environment in structuring its culture and processes according to trauma-informed school competencies to promote a student’s integrated neural functioning, which is foundational to academic success.

Guiding Principles

Informing each phase are the Four Core Values of Trauma-Informed School Practice, identified by the authors as reflecting distinctive characteristics of trauma-informed programming across all phases of practice (Trauma-Informed School Initiative, 2019).

Attachment-Focused. Attachment and attachment-focused developmental theories, further supported by advancements in neurobiology, provide concrete and practical insight into relational processes that either support or interrupt brain development. The integration of neurobiology and developmental theories also provides the rationale for the primacy of attunement and mentoring to promote neural integration, which is the key to resuming development and achieving success in the academic environment.

Attachment theory also informs TISP’s embrace of a consistent ethic of care. It advocates for attuned, mentoring, and collaborative dispositions and practices with students, as well as between coworkers and community members. These commitments support the well-being of each other and the community as a whole. This value is evident in TISP’s community-driven emphasis on the Person of the Educator, and in TISP Tri-Phasic knowledge, skills, and dispositions.

Neurobiology-Informed. Trauma-informed practitioners rely on advancements in our understanding of the neurobiology of development, stress, and trauma. This knowledge base informs the educator that students struggling in the school setting are demonstrating unintegrated neural networks congruent with common and expected developmental challenges, often exacerbated by unmitigated stress and trauma. Advances in our understanding of stress and the brain require educators to continually re-examine existing school practices, not just teaching and learning methods.

Strengths-Based. There is no doubt that unmitigated stress and trauma damage the brain and impair functioning, causing great distress throughout the lifespan. The statistics, such as those gleaned from the ACE Survey, continue to shock our senses. As difficult as these facts are to absorb, embedded in trauma-informed concepts is great hope regarding how we can effectively intervene. A strengths-based trauma-informed approach trusts that when we create attachment-focused learning communities, our efforts are healing, allowing students to increase resilience and resume development. A strengths-based trauma-informed approach trusts that when we create attachment-focused learning communities, our efforts are healing, allowing students to increase resilience and resume development.

A strengths-based approach also invites us to understand broader socio-cultural factors contributing to considerable challenges for adults in providing secure attachment bases for minor children, whether in the home or in their communities. Such insight into macrosystem factors contributing to social attitudes and behaviors reminds trauma-informed educators to not blame caretakers or systems, but view each other as partners and fellow trauma-informed students-in-training alongside educators learning the same. We will discuss this further in Chapter 10.

Community-Driven: Community as a Place of Welcome and Inclusion

Ethic of Care. Trauma-informed practice is ultimately a commitment to being in community in a manner that provides a welcome and inclusive environment fostering relational safety and well-being, the basic ingredients we all need to thrive throughout the lifespan. This value is present in all aspects of TISP. A consistent ethic of care means that the relational values educators extend to students are offered to each other as well. Caring about educator well-being is a central value as expressed in Person of the Educator practices, in recognition that attuned and supportive interpersonal relationships nurture resilience and well-being amidst the challenges of educating highly stressed students. In addition, Person of the Educator as a professional development standard promotes effective implementation of trauma-informed practice.

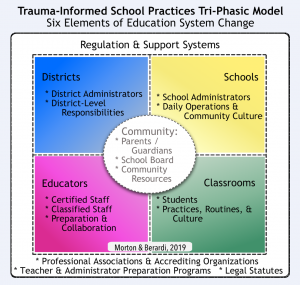

Participation by All Stakeholders. TISP is much more than providing educators with classroom strategies; it requires a system-wide change in culture and practice implemented in a developmental process requiring short-, intermediate-, and long-term planning. This system-wide implementation process requires collaboration among multiple stakeholders, as elaborated on below and illustrated in Figure 6.1. All stakeholders must be included in trainings and have a voice in the trauma-informed transition process. This includes students and parents, who are crucial partners in building trauma-informed communities. Their voices and involvement are imperative in both creating a successful trauma-informed environment and promoting student neural integration processes.

Multicultural Inclusion. Central to the relational ethics of TISP’s community focus is multicultural inclusion. Trauma-informed practice recognizes that significant stress and trauma are caused by implicit and explicit social values and mores related to aspects of our social identities that are either privileged or marginalized. Trauma-informed practice recognizes that significant stress and trauma are caused by implicit and explicit social values and mores related to aspects of our social identities that are either privileged or marginalized. These contextual identities include race, gender, sexual orientation, ability, appearance, citizenship, religion, and socioeconomic status, among others. TISP’s universal-access approach includes a commitment to understanding the influence of dominant worldviews, systems, and laws on marginalized populations and the added risk of stress and trauma this presents to students and staff.

Congruence with Established Trauma-Informed Response Models

Trauma-informed educators are part of a larger family of trauma-informed professionals. Whether trauma-informed principles are applied in clinical (psychotherapeutic) settings or in community (non-clinical) environments, unifying principles are present across all service-delivery models. For each phase, we will highlight how the Trauma-Informed School Practices Tri-Phasic Model corresponds with well-known established trauma-informed response models.

Organizational Change Process

The TISP Tri-Phasic Model is based on trauma-informed competencies designed specifically for education environments, complex systems charged with the care and development of students over extended periods of time. Therefore, the application of TISP includes organizational change strategies congruent with trauma-informed practice. Trauma-informed educator competencies focus on six system elements; each contains its own subsystems and tasks, with an awareness that all systems overlap and intersect.

Districts. District administrators are key to the success or failure of transitioning to trauma-informed practices. Trauma-informed practice requires the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and dispositions in content domains that have historically not been a part of teacher and administrative credentialing programs. It represents a change in guiding ethos and culture, a developmental process that requires clear support and leadership. In the absence of an administrator acquiring trauma-informed competencies, TISP will be reduced to a set of techniques leading to mixed messages for staff, guaranteeing lack of buy-in, misapplication of strategies, and poor outcomes.

District administrators are responsible for clearly supporting TISP, demonstrated through:

- Actively pursuing TISP competencies in order to fully grasp the knowledge base and ethos of trauma-informed education systems

- Networking with other districts and schools who have transitioned or are transitioning to trauma-informed programing

- Securing the funds to sponsor system-wide trainings

- Vetting and authorizing training in TISP

- Supporting all personnel, students, and community members (board, parents, and guardians) in TISP training congruent with context, setting, and role

- Being open to critically analyzing their own roles, school practices, and various school programs for congruence with TISP

- Intentionally creating District and School Strategic Planning Teams

Schools. Likewise, school administrators also share in prime responsibility for facilitating a successful TISP transition process. They focus on all activities, tasks, routines, and rituals of a school that occur on a daily, weekly, and seasonal basis, including such items as class transition and bell schedules; class and lunch schedules; student announcements; special assemblies; and other activities that create a school identity and culture. The school subsystem includes the school’s policies, procedures, programs, and curriculum, and specific systems like discipline policies, class sizes and space, and other supplemental programs such as AVID. It includes a school’s administrative structure and how it organizes its staff subsystems and the cooperation between those subsystems, including classroom teachers, instructional aides, parent volunteers, school counselors, school psychologists, support staff, cafeteria and maintenance staff, and bus drivers.

Educators (Certified and Classified). TISP views all staff persons that serve students throughout the day as educators. Certified educators are classroom teachers; given the intensity of their work with students, this system level focuses most dynamically on them. While the needs of classified educators are addressed under the School system, elements of relevance for them are also found within the Educator system.

This system element recognizes the need for educators to receive TISP education, training, and supervision in the acquisition of trauma-informed school competencies congruent with their role and context. To accomplish this, educators require school and district administrators to allocate appropriate support in time and financial resources. In addition, TISP-trained educators must be present on District and School Strategic Planning Teams as school subsystems are evaluated and re-envisioned to be congruent with trauma-informed practices.

Classrooms. This element focuses on the student in addition to the culture, policies, practices, and pedagogy within a particular classroom. A partial list of subsystems includes classroom culture, rules, rituals, routines, behavioral management strategies, and physical resources available to the student congruent with TISP attunement and mentoring activities. It also includes attention to the physical space, such as room size, layout, seating, acoustics, and visual stimuli such as lighting, wall color, decoration, and resource displays. TISP classroom structures, practices, and physical settings are inclusive of student voices and leadership.

Community. This fifth element of a school system includes key stakeholders who may not be regularly involved in the daily routines of a school. Most prominent are parents and guardians (caretakers), who hold the greatest investment in the academic and social-behavioral success of their children. They are central partners with educators and key to the ongoing success of trauma-informed learning environments. Part of the strategic planning process is providing TISP orientation for caretakers interested in volunteering as classroom assistants. TISP schools place great emphasis on being a community; not only are additional adult caretakers needed in this setting, but their involvement mirrors the core values informing TISP.

Community members also include the general public committed to the education of its citizens, the next generation of its leaders. Community interests are most centrally represented in school board members. These stakeholders must make informed decisions regarding how best to support administrators, schools, staff, students, and their families, including financial decisions regarding TISP training and implementation processes. TISP is also invested in its board members acquiring TISP knowledge, skills, and dispositions congruent with their context and role to ensure continuity of care throughout the system.

The final part of the Community element is the community-based resources we access on behalf of our students and their families, such as youth organizations, medical care providers, legal-aid services, housing and food assistance, and mental health care, to name a few.

Professional Regulation and Support Systems. The education profession is crafted and regulated by three external systems invested in the viability and rigor of the profession in order to maximize outcomes for students. Professional associations and accrediting organizations advocate for defining the expected competencies of an educator, while also ensuring that educators receive the necessary professional support to engage in their work. Legal statutes governing the licensing and certification of educators, as well as laws governing what a society expects of its education systems in preparing its students as emerging adults, are also instrumental in ensuring the presence of quality educators and other resources in order to maximize a student’s ability to meet those benchmarks.

Educator preparation programs for teachers, administrators, and other school-based professional roles are charged with integrating these two structural supports to mentor higher education students through the acquisition of the knowledge, skills, and dispositions of an educator. Graduates of these credentialing programs are then expected to be able to embrace their professional identities as educators, along with the tasks associated with their particular role.

This three-part regulatory and support system ideally reflects the wisdom of current educators, student voices based on current outcome data and emerging cultural shifts, and a society’s commitment to preparing all citizens to be contributing members. Given its role in preparing the next generation of educators, this system element carries a significant responsibility to adopt TISP competencies in order to produce knowledgeable and skilled trauma-informed educators. This three-part regulatory and support system ideally reflects the wisdom of current educators, student voices based on current outcome data and emerging cultural shifts, and a society’s commitment to preparing all citizens to be contributing members. Given its role in preparing the next generation of educators, this system element carries a significant responsibility to adopt TISP competencies in order to produce knowledgeable and skilled trauma-informed educators.

The process of helping current education systems update their knowledge, skills, and dispositions requires time, labor, and funds from systems short on these resources. School districts and students need regulation and support systems to jump in and begin the transformation process as well. Updated accreditation standards provide impetus to higher education programs to revise their curriculums. Fidelity to our students, educators, and the broader community requires higher education faculty to crosstrain and co-teach with their counselors/mental health educators, as credentialing boards expect licensees to demonstrate trauma-informed competencies. As these three systems are informed by advances in traumatology and learning, we provide schools the ultimate resource through qualified graduates ready to step into trauma-informed school environments, without those schools needing to invest more money, yet again, to train new staff.

The Trauma-Informed School Practices Tri-Phasic Model contained in this chapter is intended to provide a cross-check for districts transitioning to trauma-informed practices, and is a road map for educator credentialing programs to evaluate and adjust their curriculums. In Chapter 11, we envision a revised teacher standards document incorporating the competencies outlined in the TISP model.

An Integrated Model of Trauma-Informed Educator Skill Development

Educator and Mental Health Developmental Model Integration. As noted in the Preface, TISP identifies skill competencies using an integration of educator and mental health skill development models (Figure 6.2). Educator competencies are often understood through the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and dispositions. These competencies are further operationalized as proficiencies for classroom teachers. Mental health competencies are often categorized according to perceptual, conceptual, executive, and professional skill arenas. Integrating schemas found in both education and mental health models has great utility to our work here, and it is congruent with TISP, an education model representing an integration between education and trauma-informed social-behavioral science knowledge domains.

Table 6.1 An Integrated Model of Trauma-Informed Educator Development

|

|

Knowledge: Theories, concepts; practice data informing professional practice competencies |

Skills: The discernment processes, actions, and behaviors of the professional |

Dispositions: The internal attitudes, worldview, and commitments of the professional reflecting the profession’s knowledge base and practice standards |

|

Perceptual: Attuning to environmental cues; observing what we see, hear; tracking sequence of events as well as broader context and deeper layers of meaning; both spoken and implied |

Perceptions informed by knowledge base |

Perceptions utilized in discerning how to act |

Perceptions effect change in the professional |

|

Conceptual: Organizing and categorizing environmental cues according to various constructs, models, and theories congruent with one’s profession |

Conceptual ability to synthesize multiple content domains into a complex whole |

Conceptual abilities allow practitioner to discern immediate, short-range, and long-range goals, and plan accordingly |

Conceptual abilities aid in discerning a hierarchy of priorities and the ultimate purpose, meaning, or intent of a professional expectation |

|

Executive: How the professional chooses to respond; the act of discerning needs and strategies in response; actions |

Executive functioning is grounded in the wisdom of the profession as currently understood |

Executive functioning is grounded in best-practice strategies |

Executive functioning reflects professional dispositions congruent with the setting, context, and role |

|

Professional: Activities, processes, structural responsibilities, including legal, ethical, personal, practice, and organizational responsibilities congruent with one’s profession |

Professional functioning revealed in ongoing education, training; practitioner is aware of the legal, ethical, and professional competencies expected of the professional |

Professional functioning evident in education, training, and supervision opportunities, self-care practices, abiding by law and ethics of profession, and contributing to the profession through mentoring and other professional activities |

Dispositions evidenced in commitment to professional activities |

Table 6.1

Professional Development: Person of the Educator. TISP professional competencies includes an awareness that the health and well-being of the educator, the Person of the Educator, is crucial to safe and effective practice and reflects the trauma-informed value of a consistent ethic of care. This is important due to the stress associated with teaching, increasing the risk of many educators experiencing secondary trauma and/or leaving the profession. The TISP education and training process is designed to nurture engagement with trauma-informed concepts, including an emphasis on self-care, thereby maximizing TISP efficacy on behalf of the needs of students and educators. For example, choosing to strengthen one’s own self-regulation skills increases educator resilience while also modeling that these skills are necessary and beneficial across the lifespan, not just for students.

The remainder of this chapter details the Trauma-Informed School Practices Tri-Phasic Model according to the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required for each phase. The document applies trauma-informed best-practice strategies according to the purpose, goals, and context of educational settings.

This format is intended to serve as a blueprint for revising educator training programs, as well as school systems targeting their development of TISP competencies. It is not an implementation manual; the remainder of this text details strategies for implementing TISP, and is based on the theory and corresponding competencies as outlined in this document. Much of the information detailed above is repeated in summary form in order for this document to be reproduced separate from the text when in use. Refer to the above model overview when expanded definitions of key concepts are helpful.

The Trauma-Informed School Practices (TISP) Tri-Phasic Model

Description

The Trauma-Informed School Practices Tri-Phasic Model is a metaframe identifying trauma-informed competencies for all educators regardless of role. It represents a systemic approach for use by educator training programs revising curriculums to include the development of TISP competencies, and educational systems transitioning to trauma-informed programming, a universal-access framework designed for all students. It is based upon trauma-informed research integrating advancements in the neurobiology of stress and trauma, developmental theories, and best practices regarding how to help students resume development impeded by unmitigated stress and trauma. This three-phase model is both sequential and iterative.

This document does not identify specific competencies per educator role. Rather, it provides a global blueprint for successful TISP implementation to guide schools in transition, as well as educator preparation programs incorporating trauma-informed competencies as expected educator outcomes. In Sections II and III we offer specific application of these competencies to each of the six system elements identified in the Organizational Change Process in Figure 6.1.

Goal

Students are challenged by a variety of life stressors in addition to unmitigated stress and trauma, all of which impair developmental processes crucial for succeeding in the school environment. The goal of TISP is to create educational settings in which all students can actively integrate life experiences, as encoded in positive and negative neural networks, in order to enhance their capacity to effectively engage in the academic and social-emotional tasks required at each stage of their education.

Guiding Principles

TISP incorporates trauma-informed concepts summarized within four core principles:

- Attachment-Focused. Attachment-focused developmental theories, further supported by advancements in neurobiology, provide concrete and practical insight into relational processes that either support or interrupt brain development. These knowledge components provide the rationale for the primacy of attunement and mentoring to promote neural integration, key to achieving success in the academic environment. Attachment theory also informs TISP’s embrace of a consistent ethic of care. It advocates for attuned, mentoring, and collaborative dispositions and practices with students, and between coworkers and community members. This value is evident in TISP’s community-driven emphasis on the Person of the Educator.

- Neurobiology-Informed. Trauma-informed practitioners rely on advancements in our understanding of the neurobiology of development, stress, and trauma. This knowledge base informs the educator that students struggling in the school setting are often demonstrating unintegrated neural networks congruent with common and expected developmental challenges, often exacerbated by unmitigated stress and trauma.

- Strengths-Based. A strengths-based trauma-informed approach trusts that when we create attachment-focused learning communities, our efforts are healing, allowing students to increase resilience and resume development. It also recognizes that there is a complex set of factors undermining safe, secure attachment across all levels of social relationships, with no one person or system to blame. Rather, each person and system is capable of becoming a secure attachment base for students, whether at home, at school, or in other community settings.

- Community-Driven. This principle emphasizes community as a place of welcome and inclusion.

- Ethic of Care. Trauma-informed practice is ultimately a commitment to being in community in a manner that provides a welcome and inclusive environment so that each person can thrive throughout the lifespan. This includes educator well-being, a central value expressed in Person of the Educator practices, a professional development standard that also promotes effective implementation of trauma-informed practice.

- Participation by All Stakeholders. TISP requires a system-wide change in culture and practice implemented in a developmental process requiring collaboration among multiple stakeholders, all of whom have a voice in the trauma-informed transition process. This includes students and parents, who are crucial partners in building trauma-informed communities.

- Multicultural Inclusion. Trauma-informed practice recognizes that significant stress and trauma are caused by implicit and explicit social values and mores related to aspects of our social identities that are either privileged or marginalized. TISP’s universal-access approach includes a commitment to understanding the influence of dominant worldviews, systems, and laws on marginalized populations and the added risk of stress and trauma this presents to students and staff.

Congruence with Established Trauma-Informed Response Models

Trauma-informed educators are part of a larger collaborative of trauma-informed professionals. Whether trauma-informed principles are applied in education, community, or clinical mental health settings, unifying principles are present across all service-delivery models. For each of the three phases, congruence with the following established response models will be highlighted: tri-phasic recovery models, including the ARC model (Baranowsky, Gentry, & Schultz, 2005; Blaustein, 2013; Blaustein & Kinniburgh, 2019; Kinniburgh, Blaustein, Spinazzola, & van der Kolk, 2005; Herman, 1992; Shapiro, 2018); Psychological First Aid (Brymer et al., 2006; Brymer et al., 2012); and Siegel’s domains of neural integration (Siegel, 2012, 2015; Siegel & Bryson, 2012).

Organizational Change Process: A System Application

TISP identifies the knowledge, skills, and dispositions essential to creating trauma-informed learning communities. It addresses the application of trauma-informed competencies to scaffold change within the six systemic elements of educational settings, identified in Figure 6.1: Districts; Schools; Educators (certified and classified); Classrooms (including students); Community (caretakers, board members, and community resources); and Regulation and Support Systems (professional and accreditation organizations, teacher and administrator preparation programs, and legal statutes, including the laws and policies governing licensing, certifications, and student learning outcomes).

An Integrated Model of Educator Development

TISP conceptualizes trauma-informed educator development through an education and mental health integrated model whereby knowledge, skills, and dispositions are delineated according to perceptual, conceptual, executive, and professional domains. Professional competencies include an emphasis on the Person of the Educator and the extension of a consistent ethic of care to coworkers aligned with trauma-informed practice. This focus on the development and well-being of the educator also promotes effective application of trauma-informed school practices, and recognizes that educators are often susceptible to secondary trauma.

TISP Tri-Phasic Model Competencies

Primary Dispositions

Disposition 1: Trauma-informed educators create environments that promote the neural integration of their members (students and educators) in order to maximize students’ academic and social success at each developmental stage.

Disposition 2: Trauma-informed educators commit to learning the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required to implement trauma-informed practices according to their role and context in order to promote safe and effective learning communities.

Disposition 3: Trauma-informed educators are committed to embedding trauma-informed rituals and practices within the daily, weekly, and seasonal routines of a school and classroom, providing a sense of repetition that deepens internal safety and stabilization. Repetition also emphasizes that basic TISP building blocks are continual and constant, not merely a phase that is completed in order to move to the next phase.

Disposition 4: Trauma-informed educators are aware of socio-cultural factors that increase student risk or resilience, and they are committed to creating an educational environment that is welcoming, safe, and inclusive of all persons.

Disposition 5: Trauma-informed educators are committed to a consistent ethic of care whereby the relational values offered to students are extended to self and one another.

Phase I: Connecting: Attachment Part 1: Attunement

Description

Both a Phase I goal and a foundational skill embedded in all aspects of TISP, Connecting addresses the primary need of students to experience adults attuning to their affective states, current needs, and successes in order to feel both emotionally and physically safe and welcome in the school environment. It reflects the recognition that until we feel seen, heard, and valued, key indicators of secure attachment leading to the thoughts, feelings, and sensations related to safety, we cannot self-regulate (stabilize). And until we establish a sense of safety and stabilization, we cannot resume growth or daily tasks, all of which require higher-order executive functioning.

On a systems level, Connecting includes District and School commitment to creating trauma-informed learning environments as a prerequisite to academic and social success for all students. In response, District and School personnel attune to the needs of Educators (all employees), subsystems, and the interfacing of subsystems to develop TISP competencies and offer support in the training and implementation processes. Districts also take the lead to include Community members (board members and parents) in TISP orientation processes. With this greater system support, Educators are then able to begin implementation strategies with Classrooms.

Congruence with Established Trauma-Informed Response Models

This phase corresponds with the safety needs identified in Stage 1 of the tri-phasic model of recovery, the Attachment phase in the ARC model, and the initial stages of Psychological First Aid. Implementation tasks are based upon neural network integration strategies.

Dispositions:

Phase I—Disposition 6: Trauma-informed educators understand the primacy of attachment theory, and its emphasis on attunement, to the neural development of both students and adults throughout the lifespan.

Phase I—Disposition 7: Trauma-informed educators are committed to attending to Person of the Educator wellness practices in recognition of their vulnerability to secondary trauma. This includes a commitment to understanding their own relational and developmental history influencing their own neural integration, foundational to strengthening resilience and well-being.

Phase I—Disposition 8: Trauma-informed educators recognize that the success of trauma-informed practices requires involvement and support from all levels of the school system: administration, school, staff, classroom (including students), and community (school board and caretakers).

Tasks:

District and Community: Attuning to the Need for Transition to TISP

A. Create District-Based Strategic Planning Team

Phase I-1: District administrators understand that transitioning to trauma-informed practices is a developmental process. Therefore, administrators authorize a District Strategic Planning Team comprised of multi-level administrators, classroom teachers, and other school personnel (including board members and caretakers) to identify overall intent and initial, intermediate, and long-term goals. Immediate tasks are specifically identified, along with a timetable for evaluating progress and planning specifics for the next phase of the transition process. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-1.a: This District Strategic Planning Team prepares for the planning process by engaging in TISP-focused readings and trainings, and includes additional personnel who have expressed interest in trauma-informed school practices. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-1.b: The District Strategic Planning Team consults with additional sources as part of early-phase goal and task development, such as other districts that have transitioned to trauma-informed practice for strategic planning advice and trauma-informed trained educators and mental health professionals to evaluate training opportunities and programs. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-2: The District Strategic Planning Team discerns a strategy most suited for their district. This includes strategies for attuning to the needs of each school while gathering staff interest and deciding on best methods for initiating the transition process, such as whether to begin with one school or multiple schools and one grade level or multiple grade levels throughout a district, and identifying costs associated with training staff. [Executive Skills]

B. Commit to District-Wide Training

Phase I-3: District administrators and school board support trauma-informed training, including education and supervision in trauma-informed educator competencies. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-3.a: District administrators support the inclusion of board members, administrators, and caretakers (parents and guardians) in TISP trainings along with educators (certified and classified) to foster mutual learning and to nurture collaborative relationships. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-3.b: District administrators support the inclusion of board members, caretakers, and all school personnel in specific trauma-informed school practice trainings congruent with their roles. [Executive Skills]

C. Support the Change Process

Phase I-4: District and school administrators support each school and classroom evaluating, adding, and/or changing school practices and routines to promote school as an emotionally and physically attuned environment promoting an internal sense of safety and stability prerequisite to learning. This includes daily, weekly, and seasonal rituals as determined by each school and classroom teacher, and in collaboration with students. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-4.a: District and school administrators support cross-collaboration among schools to promote thematic consistency in routines and rituals in order to promote a scaffolded experience for students as they progress through K-12. [Executive Skills]

Schools

A. Create School-Based Strategic Planning Team

Phase I-5: Schools understand that transitioning to trauma-informed practices is a developmental process. Therefore, each school authorizes a School Strategic Planning Team comprised of administrators, classroom teachers, and other school personnel, including board members and caretakers, to identify overall intent and initial, intermediate, and long-term goals. Immediate tasks are specifically identified, along with a timetable for evaluating progress and planning specifics for the next phase of the transition process. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-5.a: The School Strategic Planning Team prepares for the planning process by engaging in TISP-focused readings and trainings, and by including additional personnel who have expressed interest in trauma-informed school programming. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-5.b: The School Strategic Planning Team consults with additional sources as part of early-phase goal and task development, such as other schools that have transitioned to trauma-informed practice for strategic planning advice and trauma-informed trained educators and mental health professionals to evaluate training opportunities and programs. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-6: The School Strategic Planning Team discerns a strategy most suited for their school. This includes strategies for attuning to the needs of staff and students while building staff interest, deciding on best methods for initiating the transition process such as beginning with one grade level or cohort, and identifying costs associated with training staff. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-7: As momentum builds, the School Strategic Planning Team will design subcommittees in anticipation of the need to establish policies and practices of school personnel and subsystems according to trauma-informed school practices. These subsystems and associated personnel include discipline programs and processes; TISP-trained parent classroom partners; TISP-trained instructional assistants; and the tasks and interfacing of special education, school counselors, and school psychologists with classroom teachers transitioning to trauma-informed classrooms. [Executive Skills]

B. Commit to School-Wide Training

Phase I-8: Schools support trauma-informed training, including education and supervision in trauma-informed educator competencies. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-8.a: Schools collaborate with district to support the inclusion of board members, administrators, and caretakers (parents and guardians) in TISP trainings along with educators (certified and classified) to foster mutual learning and to nurture collaborative relationships. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-8.b: Schools collaborate with district to support the inclusion of all school personnel in specific trauma-informed school practice trainings congruent with their roles. [Executive Skills]

C. Support the Change Process

Phase I-9: District and school administrators support each school and classroom evaluating, adding, and/or changing school practices and routines to promote school as an emotionally and physically attuned environment promoting an internal sense of safety and stability prerequisite to learning. This includes daily, weekly, and seasonal rituals as determined by each school and classroom teacher, and in collaboration with students. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-9.a: District and school administrators support cross-collaboration among schools to promote thematic consistency in routines and rituals in order to promote a scaffolded experience for students as they progress through the K-12 process. [Executive Skills]

D. Evaluate and Adjust Discipline Methods Congruent with TISP

Phase I-10: The School Strategic Planning Team engages in preliminary evaluation of the discipline methods used by various schools within the district, or within the school of focus. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-11: Schools may opt to commission a discipline subcommittee to more formally evaluate a current program and design needed adjustments. This subcommittee is comprised of TISP-trained (or in-training) personnel, including classroom teachers at all grade levels associated with the target school(s), school counselors, special educators, instructional assistants, and administrators responsible for behavioral management policies. [Executive Skills]

E. Evaluate Current Job Descriptions and Subsystems

Phase I-12: The school administrator and the School Strategic Planning Team or subcommittee trained in TISP collaborate to evaluate and adjust current practices per educator role and context (subsystem interactions) for congruence with TISP. This includes the roles of classroom parent and instructional aides, school counselors, school psychologists, special education teachers, and support staff as they interact with and support educators (classroom teachers) and classrooms (students). [Executive Skills]

Phase I-13: School administrators monitor adjustments to personnel job descriptions due to trauma-informed practice needs. This process ensures that all personnel are not required to merely add more tasks to current responsibilities and reflects a consistent ethic of care. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-14: The School Strategic Planning Team or subcommittee trained in TISP is commissioned to evaluate current supplemental school programs (e.g., AVID) for congruence with TISP practices and the specific adjustments being implemented within a particular school or district. This subcommittee is comprised of classroom teachers at all grade levels and other personnel associated with the target school(s) and the program(s) under evaluation. [Executive Skills]

F. Provide Focused Resources and Supports to Educators and Classrooms

Phase I-15: Pedagogical practices, including classroom management, are the processes most impacted by a transition to trauma-informed practices. Therefore, schools provide ongoing training and implementation support for classroom teachers. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-16: Schools support TISP training for instructional assistants and parent volunteers to assist with Connecting and Coaching activities congruent with their roles and in response to the needs of a particular class or student(s). [Executive Skills]

Educators—Certified and Classified

A. Commit to the Change Process

Phase I-17: Educators participate in TISP trainings and commit to mastering the knowledge, skills, and dispositions of the Trauma-Informed School Practices Tri-Phasic Model in anticipation of the scaffolded, incremental change they will be implementing in their classrooms. [Executive Skills]

Phase 1-17a: Educators recognize that while Phase I strategies can be implemented immediately within a classroom, Phase I—III strategies must be congruent with a larger trauma-informed framework and are best implemented in tandem with changes co-occurring on the school system level and in classrooms also serving the same students. [Perceptual and Conceptual Skills]

Phase I-18: Educators apply trauma-informed concepts to deepen their understanding of their own life narratives to facilitate greater understanding and implementation of TISP concepts in a manner congruent with the model. [Professional Skills: Person of the Educator]

Phase I-19: Educators learn techniques to strengthen their own self-regulation skills given their risk for secondary trauma as educators, and to model congruence with trauma-informed principles, indicating that neural network strengthening is a lifespan task. [Professional Development: Person of the Educator– Educator Affect Management]

Phase I-20: Educators participating in trauma-informed training are aware that community (board members, caretakers, and community supports), district, and school personnel are participating as well, inviting evaluation of current school rituals, routines, programs, and systems of collaboration; Educators look for opportunities to contribute to these discussions.

B. Prepare to Implement Phase 1 Strategies

Phase I-20: Educators recognize that attunement from the adult toward the student, combined with teaching students how to attune to others, builds a student’s sense of safety and self-worth, increasing receptivity to learning self-regulation skills crucial to academic engagement. [Perceptual and Conceptual Skills]

Phase I-21: Educators recognize that attuning to students is also a mentoring process whereby the act of putting words to a student’s experience helps increase the student’s ability to notice and put words to their thoughts, feelings, and needs directly, rather than indirectly. [Perceptual and Conceptual Skills]

Phase I-22: Educators learn various Connecting strategies, attachment-focused communication skills designed to foster greater levels of attunement to a student’s stated and unstated thoughts, feelings, needs, and implicit and explicit beliefs (neural networks reflecting perspective (Chapter 3), which is influencing behavior). [Executive Skills—Educator with Students:]

Phase I-22.a: Educators identify strategies for implementing these skills in the classroom. Once implemented, they become part of the rhythms and rituals of the classroom. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-22.b: As educators increase TISP mastery, they ultimately create implementation strategies congruent with the needs of their students and the style of the educator. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-23: Educators evaluate the physical attributes of the classroom, such as seating, lighting, acoustics, and visual stimuli including wall color, decorations, and learning prompts for congruence with environmental factors that promote a sense of welcome, care, calm, predictability, order (simplicity), and structure (rather than chaos). [Executive Skills]

Phase I-24: Educators practice a consistent ethic of care by examining daily rhythms and routines, communication methods, and other relational practices among and between staff for congruence with trauma-informed concepts. This includes actively seeking implementation and evaluation input from all staff, displaying curiosity and openness. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-25: Educators collaborate to discern a language system to utilize with students that does not necessarily include the words “trauma” or “trauma-informed” while clearly conveying the ethos, guiding values, and goals of a trauma-informed school. [Executive Skills]

Classrooms

Phase I-26: Educators identify vulnerable students and specific behaviors to either strengthen or minimize based on individual student observation and team collaboration. [Executive Skills: Phase I—III Preparation]

Phase I-27: Educators identify universal student needs and specific developmental behaviors to either strengthen or minimize. [Executive Skills: Phase I—III Preparation]

Phase I-28: Educators work in partnership with students, explaining the trauma-informed values and practices of the school and classroom. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-28.a: Educators actively seek student ideas and feedback for ways to enhance school and the classroom as a welcoming space, safe to risk stepping outside of comfort zones and walking with each other when stress is overwhelming. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-29: Educators intentionally scaffold relational skills of mutual support between peers that create a common narrative to make sense of challenging events experienced by a student or the class as a whole, and to gather in support of each other. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-30: Educators actively demonstrate the importance of each student to the classroom community by affirming each student and illustrating that their competence is needed for the good of the group. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-31: Classroom teachers collaborate with other educators and staff serving the same students to discuss continuity of attunement micro-skills others are using with students and/or teaching students to use with other students. This continuity reinforces safety, stability, and the internalization of the skills. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-32: Educators build on and expand the use of these strategies in support of students’ capacity to attune to and support the safety and well-being of each other. [Executive Skills]

Phase I-33: Students are included in discussions about the making of a trauma-informed school community, and their input is directly requested in creating various rituals and practices.

Phase I-34: Educators design a documentation system to capture student receptivity to the culture shift initiated by trauma-informed attunement practices. [Executive Skills]

Phase II: Coaching: Attachment Part 2: Mentoring

Description

Basic to increasing resilience in the face of recovering from a recent event (such as a local disaster or a major school or classroom disruption) or from sustained unmitigated stress and trauma is helping students achieve a sense of safety and stabilization. Phase I addresses the need for safety. Phase II addresses stabilization; it comprises its own phase, given the distinct scaffolding of social-emotional skills and practice foundational to increasing executive functioning necessary for academic engagement and learning throughout the education process.

Stabilization refers to the capacity to self-regulate in response to thoughts, feelings, sensations, and social interactions that activate trauma memories and other unintegrated neural networks. Initially, it involves learning skills and techniques to calm physiological arousal that help decrease panic-response neurochemicals, such as norepinephrine, and increase calming neurochemicals, such as acetylcholine. This then allows students to practice stabilizing techniques that address perspectives (Chapter 3) based on distorted or false perceptions and thoughts fueled by negative neural networks. This is the most challenging and lengthy process, perhaps lifelong. But as a student repeatedly experiences attuned community, increased confidence in their capacity to calm arousal, and deepening awareness of the internal thoughts, feelings, and perspectives fueling arousal symptoms, the student is much less overwhelmed by this process.

These skills increase a student’s self-awareness and compassion regarding how to respond to life challenges, while increasing awareness and empathy for those around them, all within a community of care. This is the essence of what helps a student feel safe, a precursor to engaging in academic developmental tasks, a never-ending process of (a) facing new demands that challenge their abilities (courage and confidence); (b) accompanied by the need for focused attention (immediate, short-term, and long-term memory); amidst (c) possible criticism, even failure from time to time (a sense of shame and inadequacy challenging competence); and then on to (d) mastery of that particular challenge.

The TISP Tri-Phasic Model is contextualized to educators whose role is primarily coaching students through the challenges associated with academic and social skill competencies expected at each grade level. Teaching and practicing such skills in classroom settings is different than teaching at home by caretakers or in a therapeutic clinical setting. To help students establish a sense of safety and stabilization prior to full-capacity academic engagement, educators need to teach and practice social-emotional self-regulation skills in large-group, small-group, and one-to-one settings. Educators teach and then continually coach students in the use of those skills, mentoring them through difficult social and emotional challenges that inevitably happen throughout the day.

The Coaching phase is foundational to increasing executive functioning. Unfortunately, the academic setting cannot protect a student from the social and emotional challenges of academic demands until the student has built the internal confidence to face such challenges. But an understanding of the neural functioning that is under construction in a trauma-informed school setting reminds the educator that the more a student rests in the rituals and rhythms of a trauma-informed setting, the more confidence builds over time, as does executive functioning. This deeper understanding of perspectives (fueled by unintegrated internal implicit and explicit memories) undermining executive functioning, and the scaffolding of confidence and skill-building to function in the school environment, requires educators to transform the culture and practice of a school, not just a classroom, while also looking for student gains over time.

Congruence with Established Trauma-Informed Response Models

The second phase of the TISP Tri-Phasic Model corresponds with elements of Phase 1 of the tri-phasic model of recovery. This phase details a person’s need to strengthen internal and external resources key to the stabilization that is prerequisite to working through the experiences that are the source of the dysregulation. It corresponds to the second stage (Regulation) of the ARC model, which also addresses the internal regulation needs associated with stabilization. It correlates with Psychological First Aid in that the provision of needed resources, in this case self-regulation skills, is required once a person has achieved a sense of physiological and emotional safety. Implementation tasks are based upon neural network integration strategies.

Dispositions:

Phase II—Disposition 9: Trauma-informed educators understand the primacy of attachment theory, and its emphasis on mentoring, to the neural development of both students and adults throughout the lifespan.

Phase II—Disposition 10: Trauma-informed educators understand that student behavior, in part, is often a reflection of unintegrated neural networks due to past and/or current unmitigated stress and trauma, and require the student to first establish a sense of safety and stability prior to commencing with here-and-now developmental expectations.

Phase II—Disposition 11: Trauma-informed educators understand that persons all along the lifespan are influenced by past experiences shaping perceptions and emotional responses. It is a lifelong task to understand this connection while learning to self-regulate in the face of intense emotional responses to current events.

Tasks:

District and Community

Phase II-12: Districts understand that this is the most labor- and skill-intensive element of transforming to a trauma-informed school in culture and practice, and offer ongoing TISP training, supervision, and peer support as needed.

Phase II-13: As a result of their own TISP training, district personnel and board members understand the importance of adequately resourcing schools as it relates to the neurological development of students as foundational to executive functioning. Of particular importance are adequate staffing, manageable class sizes, and learner-friendly physical settings.

Phase II-14: Districts understand that TISP requires an examination of underlying values and messages conveyed in school discipline programs and support a trauma-informed re-evaluation of existing programs.

Phase II-14.a: Districts do not view repeated behavioral disruptions as a sign of educator classroom mismanagement or student failure. Rather, districts rely on a team approach to discerning the needs of all students when disruptive events are frequent, signaling that a student’s particular needs may be beyond what can be provided in a particular class or school setting.

Phase II-14.b: Districts are aware of how classroom disruptions impair the development, including academic success, of all students, and support classroom management systems that protect and honor the needs of each student.

Phase II-15: District-level personnel and community members (caretakers and board members) continue participation in their own TISP training. [Executive Skills]

Phase II-16: Districts support School Strategic Planning Team recommendations regarding providing TISP-trained parents and educational aides as classroom support personnel.

Phase II-17: As a trauma-informed mindset is more fully grasped, districts envision a data-gathering agenda that may not be captured in current desired statistics. [Executive Skills]

Schools

Phase II-5: Schools immediately and intentionally re-evaluate discipline methods and processes according to trauma-informed program needs as this is crucial to creating a trauma-informed school culture and supporting educators implementing trauma-informed classroom methods. [Executive Skills]

Phase II-5a: Schools consult with other districts that have undergone a similar evaluation process, and investigate the accessibility and utility of various verified trauma-informed student management programs if the District and/or School Strategic Planning Teams have determined that current programs are incongruent with trauma-informed practice.

Phase II-5b: Schools understand that current student management methods may need to remain firmly in place while evaluating and transitioning to a new system, even as attitudinal and behavioral shifts reflecting Phase I (Connecting) skills can be implemented immediately.

Phase II-6: Schools provide adequate attunement and concrete response to classroom educators’ needs for immediate and ongoing support, especially during the early phases of implementing elements of Phase I and II culture through the introduction of various rhythms and routines. [Executive Skills]

Phase II-7: Schools offer a variety of resources in anticipation of a student’s need to self-regulate within or outside of the classroom. Schools are especially mindful of viewing or implementing self-regulation options not as a negative consequence, but as a sign of progress that a student is able to actively choose and/or participate in options offered.

Phase II-7.a: Schools understand the role of recreational physical activity (play) and the visual and performing arts in providing students with a method to discharge energy fueled by stress response systems, and they refrain from using these activities as leverage to motivate a resistance to behavioral impulses.

Phase II-7.b: Schools do not view repeated behavioral disruptions as a sign of educator classroom mismanagement or student failure. Rather, schools rely on a team approach to discerning the needs of all students when disruptive events are frequent, signaling that a student’s needs may be beyond what can be provided in a particular class or school setting.

Phase II-7.c: Schools are aware of how classroom disruptions impair the development, including academic success, of all students, and support classroom management systems that protect and honor the needs of each student.

Educators—Certified and Classified

A. Develop Scaffolded Self-Regulation Routines, Rituals, and Practices

Phase II-8: Educators participate in ongoing reading, trainings, and peer support to further identify and create student self-regulation skills congruent with their classroom needs. [Executive Skills]

Phase II-9: Educators understand that self-regulation works in tandem with attunement, and is a four-step, multi-skill process: (a) identifying cues; (b) self-calming in order to reduce the intensity of the cues; and then (c) reflecting on the source, need, or meaning underlying the initial activation; leading to (d) intentionally choosing how to respond. [Perceptual and Conceptual Skills]

Phase II-10: Educators understands that insight and self-regulation alone does not resolve the impact of stress and trauma. Learning this four-step process is key to widening our window of tolerance for stressful events. Increasing tolerance for the discomfort is crucial, as the underlying source and meaning (the trigger) often requires a season of time to accept, make sense of, sort out, or resolve. [Perceptual and Conceptual Skills]

Phase II-11: Educators understand that self-regulation is along four domains: affective, physiological, cognitive, and behavioral. In preparing to implement skills in the classroom with individual students and as a group, the educator is able to gather and categorize specific self-regulation activities to strengthen specific aspects of neural functioning, using such resources as Siegel’s domains of neural integration. [Perceptual, Conceptual, and Executive Skills]

Phase II-12: Educators understand that each student must practice self-regulation skills regularly in order to develop competence and confidence. These go-to strategies help maintain and strengthen processes in progress, reinforcing ongoing neural integration messages you are helping students deeply encounter. [Perceptual and Conceptual Skills]

Phase II-13: Educators understand that each student must repeatedly experience states of emotional and behavioral regulation and dysregulation in order to practice neural integration strategies designed to increase student self-awareness and confidence in one’s ability to tolerate discomfort. [Perceptual and Conceptual Skills]

Phase II-14: Educators design and implement strategies to promote affective, cognitive, and behavioral regulation, in response to the need states and perspectives (reflecting unmitigated implicit and explicit memories) and current environmental demands underlying episodes of dysregulation. [Executive Skills]

B. Person of the Educator

Phase II-15: Educators recognize that building self-regulation strategies into the classroom and school culture is the most challenging aspect of TISP requiring added attention to self-care strategies. [Perceptual and Conceptual Skills]

Phase II-16: Educators create rhythms and rituals to support the work and well-being of each other in response to the stress and potential secondary trauma associated with responding to the developmental needs of their students. [Executive Skills]

Phase II-17: Educators regularly participate in peer consultation not merely to evaluate classroom effectiveness and learn new ideas, but to debrief their own internal cognitive and affective responses to classroom challenges. [Executive Skills]

Classrooms

A. General Strategies

Phase II-18: Educators continually inform students about how the trauma-informed classroom and school (using predetermined terminology) view your time together as a learning community, including how self-regulation struggles are viewed, and how the teacher and students will be invited to respond in various rituals, routines, and practices. Educators include student voices in creating systems of response.

Phase II-18.a: Educators identify a range of activities, including visual, auditory, and kinesthetic aids, to teach and practice self-regulation skills. Scaffolded instruction and practice occur in daily and weekly rituals and routines, in designated teaching moments, and are woven into lesson plans as they relate to and reinforce class content.

Phase II-19: Educators create time to deepen and practice self-regulation skills by teaching students how to identify mild to more heightened states of arousal (self-awareness processes and accompanying ranking system) related to a particular need as expressed in thoughts, feelings, and/or sensations. [Executive Skills]

Phase II-19.a: Educators provide insight and tools for helping students increase their window of tolerance for heightened states of arousal even as they provide tools to lower or mitigate further arousal. [Executive Skills]

Phase II-19.b: Educators provide resources to students in response to internal need states for use according to level of arousal. The educator and students regularly practice identifying the need state and assessing what coping resources are most helpful or needed in the moment. Peers are coached in how to support each other in these moments. [Executive Skills]

Phase II-20: Educators teach students how to understand what is occurring within their bodies when assessing need states, teaching students about brain and body functioning in a manner congruent with student context.

Phase II-20.a: Educators support and facilitate strategies that increase a student’s competence and confidence in their ability to actively target and change or counterbalance a state of mind, whether it is a thought, feeling, or physiological response. [Executive Skills]

A. Affective and Physiological Regulation

Phase II-21: Educators will instruct students in how to identify and rank emotions and other internal body sensations (arousal states) indicating a current need. [Executive Skills]

Phase II-21.a: To reduce the intensity of these cues, educators teach and utilize self-soothing or self-calming responses, sometimes called self-rescue skills. Once a student learns how to self-calm, the student has greater access to executive functions required to process and verbalize deeper wants, needs, and perspectives underlying the activation. [Executive Skills]

B. Cognitive Regulation

Phase II-22: Educators recognize that deeper levels of cognitive insight into what ultimately fuels dysregulated behavior, whether congruent or incongruent with current social demands, is a lifelong process in varying ways; they are able to discern what is necessary in the moment to increase a student’s secure base—the internal sense of safety and stabilization needed to take the next step in their development. [Perceptual and Conceptual Skills]

Phase II-22.a: Educators prepare to help students understand how differences of opinion activate feelings and sensations that fuel discord. Self-regulation skills aimed at increasing the window of tolerance for the discomfort include dialogic cognitive strategies aimed at normalizing differing viewpoints and need-states of self and other.

Phase II-23: Educators teach students about the complexities of how our thoughts and perspectives influence and are influenced by feelings, sensations, actions, and events, using various forms of exploration and expression in activities ranging from individual and group practices to activities accompanying academic lessons. [Perceptual and Conceptual Skills]

C. Behavioral Regulation

Phase II-24: Educators understand that the process of attunement (Connecting) and mentoring (Coaching) is designed to increase student insight into a behavioral impulse even as they are being coached in the practice of increasing intentional choice in response to internal arousal states. Educators understand that when a student is in a defensive state, often they cannot necessarily answer “why” they choose a behavior, nor are they able to access executive functions needed to engage in a repair process.

Phase II-24.a: Educators explain to students how behavioral disruptions will be viewed and managed through a process of helping students self-regulate, as precursor to identifying need states underlying the behavioral reactions, and then engaging in a repair or accountability process.

Phase II-24.b: As part of the psychoeducation process of self-regulation skill development, educators help students identify thoughts and feelings influencing behavioral impulses. The source of arousal states may be related to a struggle unrelated to the current social environment, and/or a misinterpretation of current social exchanges, and/or an inability to tolerate opinions and need states of others, and/or anxiety in response to the academic demands of that moment.

Phase II-25: Educators nurture the student’s capacity to accurately read the emotional expressions of others anchored within the context of that setting. This ability helps students identify misinterpretations of the social environment fueling affective and behavioral reactions. This social skill also nurtures a supportive peer environment. [Executive Skills]

Phase II-25.a: Educators build on and expand the use of these strategies in support of students’ capacity to attune to and support the safety and well-being of each other. [Executive Skills]

Phase II-26: Educators utilize a well-rehearsed process of identifying behavioral activation cues in a student, whether a student directly or indirectly alerts peers or teachers that they are in need of using a class resource.

Phase II-26.a: Educators can easily access school system resources when a classroom needs assistance due to a student’s inability to behaviorally self-regulate, impairing the student and classmates’ abilities to maintain physical and/or emotional safety.

Phase II-26.b: Educators design and use attunement and mentoring practices to help all class members debrief shared experiences that were disruptive, scary, hurtful, and/or sad. This includes classroom events, as well as other distressing communal events such as a recent disaster, an act of violence, or an injured or now absent classmate. Educators understand how these events activate the stress response circuits of all class members, including each student’s own unmitigated stress and trauma neural circuitry.

Phase II-26.c: Educators seize the aftermath of disruptive classroom events as a time to practice attuning to class needs to have their experience acknowledged, in order to integrate that experience and return to a sense of school and classroom as a safe and welcoming space. Educators understand that this is a key underlying concept related to attachment and the formation of integrated neural functioning: walking students through processes of “connection-break-repair” in which their experience is mirrored and validated as a precursor to using executive functions to make sense of the event and continue class engagement.

Phase II-26.d: In the aftermath of a disruptive behavioral event, educators engage in an insight and repair process with the student(s). Educators practice honoring the need state of the student even while holding the student accountable for the behavior. Repair processes are enacted, along with the identification of additional internal and external resources that might be accessed now and in the future.

Phase II-26.e: Educators rely on a team approach to discerning the needs of all students when disruptive events are frequent, signaling that a student’s needs may be beyond what can be provided in a particular class or school setting.

Phase II-27: Educators understand the role of recreational physical activity (play) and the visual and performing arts in providing students with a method to discharge energy fueled by stress response systems, and they refrain from using these activities as leverage to motivate a resistance to behavioral impulses.

Phase III: Commencing: Increased Executive Functioning and Developmental Task Engagement

Description

Phase III represents a student’s increased ability to engage in executive functioning congruent with age-appropriate developmental demands, including academic and social skill competencies. Increased safety and stabilization are precursors to a student’s capacity to engage in higher-order thinking processes associated with learning. This capacity to engage executive functioning is crucial to neural integration processes. It is this recursive pattern of engagement in the school community and integrating internal neural networks that promote increased growth and resilience, which in turn allow the student to meet various developmental challenges throughout their education.

On a daily basis, educators see the impact of unmitigated stress and trauma on student learning and behavior. However, their context and role does not advise or allow for the direct therapeutic processing of these events, even though educators must work with the side effects of these events as they manifest in indirect ways. The enactment of tasks in Phases II and III differs from clinical treatment environments in that educators are not directly helping students work through traumatic memories. Rather, educators are working indirectly with traumatic memories through trauma-informed attunement and mentoring embedded in all aspects of the school day.