3

“After all, when a stone is dropped into a pond, the water continues quivering even after the stone has sunk to the bottom.”

―Arthur Golden, Memoirs of a Geisha

Desired Outcomes

This chapter and the accompanying recommended readings and activities are designed to assist educators to:

- Understand the role of attunement and mentoring in the development of positive and negative neural networks that influence academic and social-emotional functioning.

- Deepen awareness regarding the nature of the Adverse Childhood Experiences survey, the significance of ACE scores and lifespan health and functioning, and how to proceed with caution (ethically) in using them to assess student risk.

- Apply emerging trauma-informed perceptual and conceptual skills by articulating the complex interplay between various types of stressors, the quality of our attachment relationships, the development of integrated neural networks, and the role of social supports in the assessment of student vulnerability and resilience.

Key Concepts

This chapter introduces trauma-informed content domains instrumental to understanding the impact of unmitigated stress and trauma on the developing person. The intent is to deepen educators’ conceptual and perceptual skills regarding the myriad factors that contribute to risk and resilience. This knowledge and these skills will inform the creation of trauma-informed school culture and processes. The chapter includes the following key concepts:

- The ACE Survey and its assessment of family attachment vulnerabilities

- Implicit and explicit memory in the formation of positive and negative neural networks

- The General Adaptation Syndrome and the HPA-Axis Stress Response Systems, and their role in helping us manage stress and anxiety, including traumatic events

- The ABCX model of stress and coping theory

Chapter Overview

In Chapter 2 we identified basic developmental needs across the lifespan, with special emphasis on the most formative first 18 years of life. Our intent was to deepen educator awareness that TISP is not merely a response to students with traumatic backgrounds, but a universal-access education approach based on the developmental needs of all students.

In Section II we focus on methods of responding to students to create the optimum environment in which learning and development can take place. While most educators want concrete tools now because they needed to use them yesterday, we want to give you the knowledge (conceptual skills) that leads to the dispositions of a trauma-informed educator, so that then you can make sense of the skill set. And while we will give you plenty of concrete tools, we want you to be able to create your own and evaluate any tool, activity, or program that others might give you for its congruence with trauma-informed thinking. Having a firm grasp of the conceptual elements informing trauma-informed practice is key to developing trauma-informed expertise. Having a firm grasp of the conceptual elements informing trauma-informed practice is key to developing trauma-informed expertise.

In this chapter we focus on what happens to students who are overwhelmed by stress and trauma and do not have adequate social supports necessary for successful coping. Children who cannot cognitively, emotionally, and physically self-regulate in age-appropriate ways may be showing the side effects of unmitigated stress and trauma. And often—not always—these students are experiencing attachment disruptions at home, where their caregivers struggle with adequately perceiving and/or responding to the child’s need for social and emotional attunement and mentoring. In parent-training materials, this attunement and mentoring process is often grouped into two attachment-focused categories called nurture and structure (Clarke & Dawson, 1998). This need for attunement and mentoring is not met solely by parents, but by all community members invested in the health, growth, and future productivity of children. Hence, school-based social interactions between staff and students, and between peers, are also formative for a child. It is crucial to understand that a child’s growth is supported or undermined in multiple environments, lest we place all the responsibility on parents. Schools traumatize children. Social and political unrest traumatize children. Crime and natural disasters traumatize children, among other types of conditions and events.

We begin with an overview of the impact of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Survey (ACE) and corresponding data that has shaped public awareness and response (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019; Felitti et al., 1998). We clarify its meaning, as it provides insight into hypothesized negative neural networks that may be undermining student school success. We will then expand our understanding of the impact of stress and trauma by examining two innate trauma-response systems: the norepinephrine-driven flight-fight-freeze response and the long-term cortisol-driven General Adaptation Syndrome (Everly & Lating, 2012; van der Kolk, 2014; Vermetten & Bremner, 2002). To help us see the myriad factors that can increase or mitigate our vulnerability to stress and trauma, we will apply family stress and coping theory (McCubbin & Patterson, 1983) as a metatheory designed to not only assess vulnerability versus resilience, but further inspire hope that we can intervene effectively with our students to help them be successful in school. The final concept presented is an elaboration on the formation of neural networks, their central role in dictating a student’s ability to function in the school environment, and the key to understanding how to effectively intervene with students who are dysregulated due to unmitigated stress and trauma.

We will then walk you through an application of the concepts discussed thus far as we explore the likely social context, experiences, and risks and resiliencies of Charlotte, introduced in Chapter 2, and Ben, introduced in this chapter. Our intent is to help educators see what lies beneath—what happens on a physical, emotional, and cognitive level when a student experiences stress and trauma within the particulars of their larger social context. We also want to illustrate the complexity of the developmental concepts informing TISP to guard against relying on sound bites and perhaps missing a more multidimensional way of understanding stress, trauma, and the developing child. This added insight builds trauma-informed educator dispositions, including deeper insight into the role of school as a place for investing in the growth of a child, and doing so by first building school environments informed by the student’s attachment needs as foundational to learning.

We end this chapter by inviting you to gather in educator discussion groups and use the worksheets we provide to apply concepts presented thus far in order to deepen your own understanding of stress, trauma, and resilience and more deeply attune empathically to the vulnerabilities of each student.

Adverse Childhood Experiences Survey—A Corrective

During the 1990s, a group of researchers led by Felitti and Anda set out to gather data to support a hypothesis many correlation studies have suggested for decades: That childhood stress and trauma have biological, emotional, cognitive, and social impacts that follow a person throughout their life (Felitti et al., 1998). A joint venture between the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Kaiser Permanente (CDC, 2019), the process was simple: assess the level of stress the person likely experienced during the first 18 years of life, and compare that to indicators of physical, emotional, and social functioning over the lifespan. The researchers created a 10-item questionnaire, called the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Survey, and enlisted Kaiser-Permanente medical care providers in southern California to administer the survey to their patients. They then compared the medical history of respondents with their ACE scores.

Figure 3.1: Adverse Childhood Experiences Survey (Original Version)

Finding Your Score

Circle or mark “No” or “Yes” to the following 10 questions. Add up your “Yes” answers. This total is your ACE score.

While you were growing up, during the first 18 years of life:

- Did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often swear at you, insult you, put you down, or humiliate you? OR Act in a way that made you afraid that you might be physically hurt?

No

Yes - Did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often push, grab, slap, or throw something at you? OR Ever hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured?

No

Yes - Did an adult or person at least 5 years older than you ever touch or fondle you or have you touch their body in a sexual way? OR Attempt or actually have oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse with you?

No

Yes - Did you often or very often feel that no one in your family loved you or thought you were important or special? OR Your family didn’t look out for each other, feel close to each other, or support each other?

No

Yes - Did you often or very often feel that you didn’t have enough to eat, had to wear dirty clothes, and had no one to protect you? OR Your parents were too drunk or high to take care of you or take you to the doctor if you needed it?

No

Yes - Were your parents ever separated or divorced?

No

Yes - Was your mother or stepmother often or very often pushed, grabbed, slapped, or had something thrown at her? OR sometimes, often, or very often kicked, bitten, hit with a fist or hit with something hard? OR EVER repeatedly hit over the course of a few minutes or threatened with a gun or knife?

No

Yes - Did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic or who used street drugs?

No

Yes - Was a household member depressed or mentally ill, or did a household member attempt suicide?

No

Yes - Did a household member go to prison?

No

Yes

Add up your “Yes” answers. Total:_____

Figure 3.1 https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/about.html

The ACE Survey was intentionally limited in scope. Of all the hundreds of traumatic events a child might experience (and pre-existing instruments to measure them), the researchers narrowed their focus to adverse experiences that might occur in the home, with the exception of one question inquiring about sexual abuse that may or may not have involved a family member.

These 10 questions only assess events that are indicative of a pattern of parental disruptions to providing safe, secure, consistent attachment to minor children in the home. Failure to provide good-enough parenting, as we discussed in Chapter 2, then sets the child on a course of increased vulnerabilities to additional life stressors. All of us need one or more stable and reliable caretakers during our formative years in order to build the neurological structures—the internal schemas—needed to be resilient. To deal with daily expectations, whether they involve relational stress, disappointment, or age-appropriate demands, we need consistent, stable attachment relationships first. To learn, we need to engage from a stable attachment base. To deal with the inevitable traumas that life throws our way, we need that internal stable base. A child who experiences bullying at school has a better chance of that adverse event not disrupting their ability to cope if they have safe and attuned parents to reach out to for help. If the child does not have that home base as a relationally safe place, the child is already stressed and vulnerable to further negative side effects when besieged by other stressors. The absence of other traumas from the original survey is not to suggest that those adverse events are not disruptive or damaging to the developing child. But the researchers wanted to focus on primary attachment vulnerabilities, as primary attachment is the foundation upon which the ability to successfully navigate all additional stressors rests.

The international version of the ACE Survey (World Health Organization, 2018) recognizes a host of other non-family adverse events that may be just as disruptive to a child’s development, such as war, social unrest, and cultural customs abusive to vulnerable populations that induce severe psychological injury regardless of a child’s primary attachment relationships. This is only acknowledged in the original 10-question survey with the addition of a question regarding sexual abuse.

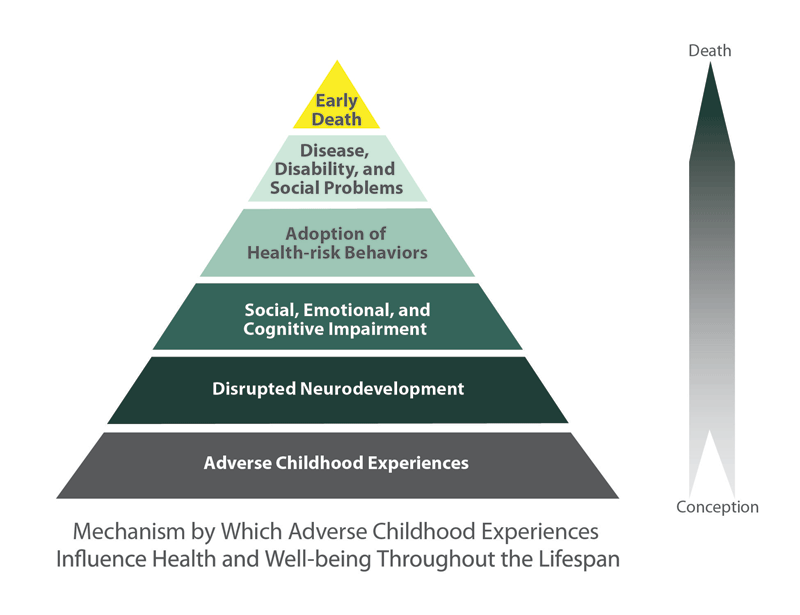

As the researchers began tallying up the number of adverse childhood experiences and comparing them to the biopsychosocial functioning of those persons across the lifespan, they were startled by the results: The higher a person’s ACE score, the more likely that person faced significantly greater lifecycle challenges, and the jump between one ACE score and the next showed an exponential increase in lifecycle struggles (CDC, 2019). See Figure 3.2 below for a graph depicting life cycle vulnerabilities that increase with higher ACE scores. The bottom level of the ACE pyramid indicates that an ACE score is predictive of lifecycle challenges. The next level of the pyramid highlights that adverse childhood experiences disrupt neurological development. The third level indicates the resulting social, emotional, and cognitive impairment. The fourth level indicates how vulnerable the person is to then engaging in high-risk behaviors. The fifth level indicates how high-risk behaviors increase vulnerability to disease, disability, and social problems. The sixth and final level of the pyramid signals an early death as a culminating consequence. Visit the SAMHSA (2017) and CDC (2019) websites for a sampling of these results, and you will begin to understand why they have generated global alarm, inspiring trauma-informed institutional practices worldwide.

Figure 3.2: The ACE Pyramid

The concern is not just about the correlation between home-based adverse childhood experiences and lifespan challenges, but the percentage of the population with elevated ACE scores whose adult profiles indicate significant struggle. While mental health professionals have always surmised that at least 30% of the population experienced adverse childhood experiences, current ACE data suggests that perhaps more than 50% of adults have experienced a significant number of these events, producing lingering adult effects. These statistics have greatly motivated communities to respond (Anda, et al., 2006; Massachusetts Advocates for Children, 2013; Prewitt, 2014).

Limitations of the ACE Survey

As with all surveys, remember the social setting in which the survey was first created—in this case, the United States. Given the social unrest occurring in many of our communities now, we are aware of the relevance of the international ACE version (World Health Organization, 2018), as the theory underlying the additional questions may also apply to various populations not considered in the original ACE Survey. The case example of Ben at the end of this chapter will illustrate this.

Many of our adult students have also commented on gender bias present in question #7 related to violence between parents, assuming that only violence against women occurs, and violence against men does not occur or is not as traumatic to a child. When a respondent is trying to discern their ACE score, we invite them to make the necessary adjustment in question wording to describe the type of domestic violence they may have observed in their home.

And finally, we often encounter respondents who find that the ACE Survey does not capture the pain of their childhood. These are persons who report families where they did not feel seen or heard. They describe parents who were emotionally distant, overly invasive, or a mix of those two extremes. No overt abuse, no clear-cut adverse events other than what is captured by question #4; just continual emotional abandonment or manipulation. Their injury is one of not-good-enough attachment as well. Their developmental vulnerabilities will not be readily predicted by an ACE score, but they are vulnerable just the same.

Likewise, as we see in our case examples with Charlotte and Ben, adverse events alone are not 100% predictive. ACE scores do not identify respondents who may have experienced safe parent-like adults who helped them mitigate losses or disruptions within their childhood homes. ACE data also invites additional study to identify persons who developed internal strengths and resiliencies precisely because of what they learned coping with home-based adversity. We caution educators not to use an ACE score out of context or consider it determinative. It is merely a tool for quick insight into the home environment, not an exhaustive assessment. This is why we are placing detailed emphasis on the nuts and bolts of how we ultimately become more resilient versus more vulnerable when faced with either age-appropriate and expected stress, such as school performance demands, or traumatic adverse experiences.

The Ethics of Administering ACE to Minors

The ACE Survey and current data are powerful. More than any other previous study regarding the impact of stress and trauma on functioning, ACE results have motivated communities to respond through a variety of trauma-informed initiatives. For these reasons and more, data gathering needs to continue, and we support that process. In fact, Brenda, in her work with preservice teachers, is comparing ACE scores with empathy and classroom management, exploring whether or not an elevated ACE score coincides with greater levels of empathy.

But we have witnessed both naive and potentially egregious uses of the survey with students under the age of 18. This is one reason why we advocate that educators become experts in trauma-informed practices—in this case, understanding the purpose and limits of psychometric assessment devices, and not using results in a manner beyond their scope of competence and practice. As we mentioned in our Preface, trauma-informed educators will also refrain from referring to someone or labeling someone according to a test score.

We have observed in documentaries and stories from educators and students that the ACE Survey has often been administered in K-12 settings as schools seek to respond to the profound impact of unmitigated home-based stress on many of their students. We share in the alarm; it is what motivated us to write this text. But we are observing some fairly predictable bad habits brewing that reflect the need for educators to develop the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary to create trauma-informed learning environments.

We invite all educators developing trauma-informed competencies to understand some of the basic rules and best practices associated with administering surveys (instruments) designed to assess a person’s psychosocial functioning. For an orientation to the ethics of utilizing psychometric devices, various codes of ethics related to such devices are referenced here for your review (American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy, 2015; American Counseling Association, 2014; American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education, 2014).

One primary issue is a respondent’s (and in particular, minor student’s) right to informed consent, starting with a description of the theme and purpose of the ACE Survey, why they are being asked to take it, and what you will do with their results. The survey administrators need to understand that when you explain (even in softer language than used here) to a student that the quality of their home relationships may lead to lifelong problems and an early death, that is emotionally distressing and misleading. Students from stressed homes may be getting something good-enough that you do not know. But even if ACE scores were 100% reliable, you are not serving students and their need to become resilient by telling them overtly or via implication that their home environment is bad for them. We undermine hope and instill panic when we tell kids that something is wrong with them because of the stress in their home. They love their families, and they cannot change their home environment; they need school to be a place that helps nurture these family relationships, not label and judge them. Students and parents need to know that the relational values we are promoting at school, we are also extending to parents.

Given the nature of the survey, we are not sure that it is ever appropriate for educators to administer the ACE to minor students. Through relationship with our students, and understanding their family and community contexts, we can surmise the level of home-based stress that might be occurring. You do not need ACE scores to prove your students are stressed; you already see the side effects on a daily basis. But perhaps most important, TISP is a universal design approach to education: Its elements serve the needs of all students to help them meet the academic and social challenges of the school environment. It is not designed for schools based on ACE scores. And if educators understand the intent of ACE, what it is teaching us about vulnerability, there are other ways to more relationally invite students to share about the level of stress in their lives, while giving them the tools to cope and be more resilient, all while honoring and supporting their bonds with family. We know all students are at risk; we don’t need ACE scores to prove it. Students need you to see them, to know them—not through a survey, but through the context of relationship.

Should adult students learning about ACE and its correlation to healthy lifespan functioning take the survey as part of class? Of course! It is available online, and once they learn about it in class, most will hop online and take the survey. And chances are they may have a medical provider who will invite them to take the survey someday. There is no better way to take the survey than with guidance from a trauma-informed trained educator who can walk them through the instrument and help each student make sense of their results within a broader conceptual framework.

Human Stress Response Systems

You may be noticing that for almost every piece of difficult reality about the nature of being alive and surviving all the challenges life throws our way, there are these nuggets of hope, life preservers that are all around us to help us cope and seize the joy and goodness that is waiting for us between and amidst the struggles. Our innate ability to physiologically handle stress, fear, and trauma is one of those life preservers, albeit with all the typical limitations we might expect.

When our body picks up cues that there is a challenge—anything from a mild daily task we may need to finish to an all-out danger—a message is immediately sent to our autonomic nervous system (comprised of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems) that it’s time to step it up so we can meet the demand. The cue to act is received by the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), whose job it is to have “sympathy” for our need to act. This is accomplished by the release of just the right amount of norepinephrine, the precursor to adrenaline, to give us the energy and mental acuity to get the job done. Meanwhile, the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) is aware that the SNS is expending lots of energy and needs a break now and then to rest and recharge. Its job is to release just the right amount of neurochemicals, acetylcholine among them, to signal the SNS that it did a good job and can now relax. These two systems are in a continuous ebb and flow relationship 24 hours a day, autonomically, often without our awareness. The SNS dominates during the day, getting necessary breaks, thanks to the PNS, when we are still and relaxed; the PNS dominates at night, even though the SNS is responding to all sorts of cues to act even as we sleep. This ebb and flow, with some self-care and attention, runs like an energy-efficient furnace with a fine-tuned thermostat facilitating self-regulation.

When an emergency arises, perceived (such as a nightmare that you are being chased by dragons) or real (when physical or emotional safety is truly under threat), the autonomic nervous system (ANS) activates one of our two internal stress response systems: the locus coeruleus/norepinephrine response commonly called the flight-fight-freeze response (Everly & Lating, 2012; Van Der Kolk, 2014; Vermetten & Bremner, 2002). In this situation, a higher dose of norepinephrine is needed so we can hyper-energize systems designed to help us run if we perceive we can escape the situation, fight if we perceive we can’t get away, or freeze, which is a highly sophisticated bodily process that says, “OK, your only chance of survival is to play dead so this threat moves on to something else.”

Within seconds of the flight-fight-freeze activation, our bodies kick in our second innate stress response system, the General Adaptation Syndrome (Everly & Lating, 2012). Driven by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis, our bodies now rely on cortisol, often called “the stress hormone,” to prepare for the possible long-term energy needed in response to the danger (Berardi & Morton, 2017).

Norepinephrine and cortisol (among other chemicals) are amazing pharmaceuticals our body keeps in store for just such a moment as an emergency. They help us with clarity of mind, sharpen our eyesight, and give us increased strength and hope. But it comes at a cost, which our bodies can tolerate as long as the state of emergency is temporary. Both of these stress response systems rob energy from one place to feed another. For example, cortisol steals energy from your immune system, and impairs your ability to absorb nutrients from food. While you are out fighting dragons, you don’t need to be fighting cold germs, and you can use energy reserves already stored in your body for fuel. Norepinephrine stops or slows your digestive process; you don’t need to use energy to digest food, and in fact, it might be a good idea to keep it stored in your stomach until later when you do need to metabolize those calories to replenish after all that running from dragons. We say this tongue-in-cheek, knowing that some of the functional abilities we gain when our alarm systems go off are not necessarily needed for all emergencies, but it is good to know how these life preservers work, and their limits. For all its strengths and limits, after the emergency has been resolved, our body is wired to return to homeostasis. All systems signal each other, “Job well done; danger is over and everything can go back to business as usual.”

Perhaps the biggest warranty limit is a caution to avoid overuse. When our stress response systems are constantly activated, the body has an increasingly difficult time returning to homeostasis, that sense of calm within the natural rhythm of the ebb and flow of various bodily systems working in sync. Once the circuitry of one system can no longer return to homeostasis, more stress is placed on other bodily systems, and the effect is like tumbling dominoes. We will return to this later as we identify the hurdles an overly stressed student faces just in terms of dealing with dysregulated physiology, let alone unintegrated neural networks. But for all of us who mumble to ourselves that students should be better able to self-regulate amid the clamor of a classroom, focus more, tolerate frustration, delay gratification, not be so sick all the time, etc.—yes, you are picking up something that’s amiss; you are seeing students whose bodies and minds are not meeting various benchmark expectations because they are overstressed, and in their own language, they are screaming at us to look and listen. But for all of us who mumble to ourselves that students should be better able to self-regulate amid the clamor of a classroom, focus more, tolerate frustration, delay gratification, not be so sick all the time, etc.—yes, you are picking up something that’s amiss; you are seeing students whose bodies and minds are not meeting various benchmark expectations because they are overstressed, and in their own language, they are screaming at us to look and listen.

Stress and Coping

Family stress and coping is a metatheory identifying elements of resilience (McCubbin & Patterson, 1983). Its very title is somewhat confusing. McCubbin and Patterson were among the earliest social science researchers to study resilience from a systemic point of view, surmising that coping with stress and trauma is not merely about the will of the individual, but a communal process—it takes a village to survive. Coping with stress and trauma is not merely about the will of the individual, but a communal process—it takes a village to survive. Stress in this theory is defined very similarly to how we are using the word in this text—a demand that life is presenting us, requiring us to act, that activates our stress response systems. The stressor can be a mild annoyance or a life-ending event. Generally, the theory looks at the impact of stressors that most of us would label as traumatic, as well as the impact of stress pile-up, whereby numerous mild, moderate, or severe events bombard us, overwhelming our coping mechanisms. That last mild stressor may become the proverbial straw that breaks the camel’s back. This theory looks at why some of us are more resilient in the face of stress pile-up, while some of us are not.

In this model, coping does not merely mean getting by, with the negative connotation the word is commonly given today. It means healthy thriving, doing well, and on our way to resuming or continuing health and growth, not merely surviving (McCubbin, Sussman, & Patterson, 1983; Rosino, 2016).

This metamodel is useful for us as it reiterates themes we have already discussed regarding the role of internal resources (for example, neural networks) and external resources (the role of the community). It also provides a visual to help us identify concrete ways to support resilience, helping us understand the challenges facing students and educators, as well as giving us a road map in response.

The ABCX of Stress and Coping

The stress and coping metamodel creates a simple visual to assess and identify ways to strengthen resilience: A+B+C=X.

A—Nature of the Event

For all the talk about factors that increase our resilience, there is no getting around that some events are more traumatic and devastating than others. For example, much of the research investigating the impact of divorce on children supports that chronic marital discord is more damaging to a child than an amicable divorce (Wallerstein & Blakeslee, 2018). We now can understand the science behind those findings: A child subjected to constant anger and animosity, whether observed between parents or directed toward the child as well, is neurologically impacted by poorly developed positive neural networks and dominant negative neural networks, as well as hijacked and dysregulated stress response systems. This impairs biopsychosocial health. It doesn’t mean children such as Charlotte, described above, are not stressed and grieved as a result of their parents’ divorces. But it does mean that students who have limited access to safe, calm, constant attunement and mentoring are most vulnerable to stress pile-up, and hence limited ability to cope. We will see this vulnerability in Ben, whom we introduce below.

The tragic death of Charlotte’s mom would have a chance of undermining whatever positive neural networks had developed if her relational environment cannot attune to her in a good-enough way before, during, and well after her mother’s death. The nature of this psychological injury, which has neurological (physical) correlates, depends on the type, intensity, and context of the trauma. The threat of injury to self or another, the level of public shame versus community support, and the duration of the event—all of these and more influence the psychological and physical assault on the child or adult experiencing the stressor event. And, sadly, we have little to no control over this. Traumatic events, whether human caused or otherwise, happen. We can only prevent so much; the rest is up to forces outside of our control.

What the ACE Survey has revealed is that the percentage of our students who experience a high rate of chronic distress in the home, the type of stress that inhibits the development of neurostructures needed to learn and engage in prosocial behavior, is astronomically higher than previously thought—likely over 50% (CDC, 2019). And this is just capturing the families most unable to provide the type of attachment environment vital to healthy development. Many more children are parented by adults who were denied the type of attunement and mentoring they so desperately deserved, sending them into adulthood unable to provide secure attachment for their children even though their interpersonal relationship struggles are not captured by elevated ACE scores. And other children are highly impacted by neighborhood or communal threats to their safety on a daily basis. These children are also stressed and vulnerable to stress pile-up and dysregulated functioning in response. They have no choice but to live within these environments; they have no power to limit or stop the chaos around them.

Yes, Reality Bites, But …

We know with increasing confidence that many of our students live in violent, chaotic, emotionally hijacked or disconnected homes and communities, at all economic levels, in which physical and psychological safety does not exist. This reflects a significant level of dysregulation pulsing through all ages and levels of society. A trauma-informed lens cautions us to not blame parents; they (we) are all frogs in the pot, slowly being impacted by something bigger than we can fully understand, let alone know how to rectify.

This issue is of primary focus to systems therapists and researchers, and influenced the work of Geoffrey Canada, founder of the Harlem Children’s Zone, as chronicled in Whatever It Takes (Tough, 2009). Canada became exasperated by historical approaches to combating the social-emotional problems associated with generational poverty. Recognizing that a complex set of issues perpetuate generational marginalization and struggle, Canada took to heart the impact of attachment on the child’s developing mind and created neighborhood attachment-focused parenting classes. He trusted that we could help pave the way now for the next generation of adults to have the internal resources to break generational patterns, and the key was by simply fostering good attachment at home, and then continuing that level of care at school. As you read about his work and the relational stance he asks his teachers to take in how they see and respond to students and parents, you are witnessing one of the first trauma-informed school cultures before trauma-informed schools were on our radars.

So, while we are taking a bit of a depressing walk through the terrain of things, trust that there is something we can do despite the enormity and complexity of the issues that created this current state of affairs. Attachment-focused education is not a fad, not a mere theory; it is based on solid evidence that relationships do matter—they do wire our brains and make or break our ability to engage in the academic and social challenges of the school environment.

B – Resources, Internal and External

Here is where you and I have some element of control, in that we can access tools to help us when stressed, or in the aftermath of an adverse event. Internal resources, at the most basic, are what we draw on internally to help us cope. They include personality traits such as introversion or extroversion, the capacity to lead with thoughts versus feeling sensations, the preference to be orderly or to function in chaos, the tendency to be an optimist or a pessimist. Notice the personality traits are highlighting typical opposites; different types of stressors call for different responses, and we each have the capacity to use our dominant traits to our advantage or strengthen non-dominant traits as needed. We have control over that. With practice, the extrovert can learn to draw on the strengths of their inner, less dominant introverted side when their safety demands a lower profile. A person who thrives in chaos can learn to be more structured when the situation dictates, such as responding to the fragile medical needs of a loved one requiring regimented care. And we can all learn what traits, such as a sense of humor regarding the limits of self and others, tend to help the sour, bitter aftertaste of life go down with less pain on our psyche. Activities such as art, music, play, dance, spiritual practices, a walk in nature—all of these and more remind us of the good things in life, give our stress response systems a break, and help our left and right hemispheres talk to each other to sort out what’s next in life.

External resources are tools outside of us—access to a livable wage, healthy food, medical care, education, job training, transportation, a safe place to live, kinship networks, and community supports. We have limited control over these elements as they are highly dependent on the larger culture’s commitment to sustainable communities. But if they exist, and we are physically and emotionally able to nurture or access these supports, they are tools that help us take back control of our lives when adverse events threaten to undermine our health and functioning.

Many of our students attend school with impaired access to their internal resources, even while school is a place where educators can link them up with external resources as those needs become identified. But what this metatheory highlights is that both internal and external resources are required for resilience. TISP teaches us to be mindful that we are building students’ internal resources so they can then learn and engage in prosocial interactions.

C – Perspective

Stress and coping theory proposes that this is the element of resilience that we have the most power over, and the most influential in helping us cope. Perspective is a thinking process reflecting innate, deep, conscious and unconscious beliefs influencing how we assess a challenge and devise a plan in response. In the movie Life Is Beautiful (Cerami & Benigni, 1999), a father seeks to protect his son from the horrors of living in a Nazi concentration camp. He, his family, and community were being systematically stripped of their humanity, tortured, and killed. Yet he wanted to protect his son. Like Victor Frankl (2006) in Man’s Search for Meaning, the only thing he had power over was his internal thoughts reflecting deeper held beliefs or perspectives. In this way he could protect his son by trying to shape his son’s inner worldview—in this case, helping him see the beauty that surrounded them each and every day amidst the barbed wire and the sights, sounds, and smell of death.

One of the most influential researchers on resilience was a medical sociologist by the name of Aaron Antonovsky (1979, 1987). He noted that most of the time we ask why people get sick or crumble under stress, but he was curious about why some people exposed to infectious diseases or social stressors did not get sick, or did not crumble. He noted that much of the time we seek protection by wrapping ourselves in a bubble of sorts; we try to stay away from germs or stressors. But we are bombarded by all sorts of noxious things in the air and within our bodies that our immune systems and coping resources (much of the time) take care of without us even realizing. Why is that? Of particular interest here, Antonovsky wanted to know why some people who survived various traumas seemed to do well and even report greater levels of hope, insight, or groundedness than those who were never exposed to such challenges. It represents a switch from focusing on avoiding pathogens (pathogenesis) to nurturing resilience and growth (salutogenesis).

A factor common to those who cope well is their internal belief system, what Antonovsky called sense of coherence (SOC) and identified as the most significant factor in our control that makes or breaks our ability to thrive (Antonovsky, 1979, 1987). Basically, SOC is comprised of three basic ingredients: When you and I can (a) make sense of what is happening to us or around us; (b) discern and have access to culturally available and acceptable resources in response; and (c) believe that life, and the meaning we hold, make it worth coping, we are both motivated and effective in meeting life’s challenges. This internal mindset promotes strong coping skills and resilience. We often have little to no control over what happens to us, but we can control how we respond. However, this element of coping requires us to access positive neural networks to stand in relationship with negative neural networks in need of taming. Hence, a strong internal SOC is built upon a foundation of attunement and mentoring. We can’t just tell a person what to think and believe and then expect coping to increase; it springs from internal confidence built through consistent attunement and mentoring.

There’s More to the Story

It is sobering to ponder the role of perspective, of our sense of coherence, in successful coping. And it is exciting to see the resonance of Antonovsky’s hypotheses with our advances in how neural networks shape our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, key to our successful coping in the face of stress and trauma. But Antonovsky’s work also helps us understand how hate and bigotry become normative. If his work on SOC has you curious, read more, as you may find it fascinating.

He begins by explaining that SOC is not formed or based on any form of external moral code; rather, it is a deep-seated way of viewing the world that a person’s community said was right and good and the way things are. If those rules and viewpoints work in your favor—your community loves you and supports you, and you fit into that community—then the SOC you inherited from that community will work for you. But if you are on the losing end, if you are deemed a problem, especially if they knew the real you, or the available culturally accepted resources are not meant for you but only for others, then the SOC given to you by your community will not work for you, and your coping will become marginal, at best.

Antonovsky’s SOC helps us understand why marginalized communities, whether that vulnerability is based on gender, race, ethnicity, nationality, sexual orientation, appearance, or socioeconomics, are so vulnerable to stress, and in particular, unmitigated stress and trauma. Likewise, it invites us to ponder why it may be so difficult to effect change in groups whose mindset overtly invites and authorizes ostracizing others: We are tampering with that person’s core way of understanding the world. When an SOC is shaken apart, there goes that person’s way of making sense of life. And there go their coping skills, until they have the hope and confidence to learn new ways of understanding self and other in the world, and surround themselves with new resources congruent with how life is now understood.

In many ways, this is what trauma-informed schools are doing: We are challenging a child’s SOC that says love and care is only for others; academic abilities are only for smart kids; the future holds nothing for kids like me. They have learned how to adapt to a hurtful SOC, in ways that bring them further struggle, but they are doing the best they can at learning the rules of how to survive given the lay of the land. We are trying to help them see a new and different reality based on us changing that reality, seeing their worth, and investing in them through our care.

X – Level of Coping vs. Distress (Crisis)

Finally, the unique mix of each person’s encounter with a stressful event (A), access to resources (B), and ability to make sense of it through the grid of our inner neural networks (C) dictates how well we cope (signs of health and thriving) when we experience crisis or distress, whether for a season or longer (X). (While the theory uses the word crisis to indicate not functioning well and vulnerable to further risk, we use the word distress to avoid confusing it with Erikson’s use of crisis, which means something quite different.)

Coping with distress is not an either/or thing; it exists on a continuum, and commonly changes from day to day, and qualitatively over time. Charlotte likely was experiencing ebbs and flows of distress over a period of years, as her mother’s illness followed shortly after her parents’ divorce. But other factors in her life helped her continually move back toward the side of coping, even while we know she could easily get yanked into being overwhelmed, moving to distress. Ben, who we will meet in this chapter, has so many strengths, yet factors beyond his and his parents’ control are threatening to drag him into a state of chronic distress.

Imagine what our students experience when there is overt violence and abuse in the home, where their personal safety and their worth is undermined on a daily basis through harsh words and disdain. The nature of these repeated events is extreme; their access to resources is almost nonexistent; the mentoring they need to form an adaptive sense of coherence is not happening, allowing neural dysregulation to take hold. Sadly, a mere sign of strength is not hurting themselves or others, just existing. Expecting anything more is too much.

Case Example: Applying Stress and Coping Theory

The theoretical constructs presented in this chapter all talk to each other, giving us a visual of the multisystemic ways in which stress and trauma impact our body and mind, foundational to our capacity to learn and be social. We end this chapter by applying them to hypothetical students, and then asking you to do the same with students under your care.

Charlotte Revisited

In Chapter 2, we met Charlotte, who had experienced two significant traumas—the divorce of her parents and the death of her mother due to cancer. We can surmise that she experienced long-term stressors before, during, and after both events, given the nature of these traumas. Charlotte is not unlike many of us, in that we all experience bad, hurtful, sad, scary, sudden, unpredictable, and long-term stressful or traumatic events from time to time. The daily drip of stress, such as a parent’s illness, relationship discord, economic uncertainty, unsafe communities, political unrest, socially sanctioned bias and antagonism—the list of possibilities is endless—as well as distinct traumatic events such as death, divorce, and family or community violence will and do challenge all of us, and knock us off our game for awhile as we acclimate to new realities.

But Charlotte had a well-anchored responsive community that tracked her needs and responded likewise. And despite her parents’ divorce, her family relationships were characterized by protection and goodwill. Beginning with her parents, Charlotte knew they were relationally safe, allowing her to fully feel the grief of their divorce and all the fear and confusion that this event puts upon a child. She could take refuge in both parents, receiving validation, comfort, and assurance along the way. Her extended kinship network provided a well-trusted safety net long before her mom became ill. These relationships did not spare Charlotte in her grief; she still suffered a season of incapacitation in one form or another, and she will cycle through seasons of grief perhaps for the rest of her life. But her community—family, friends, and her school—gave her a way to be loved and safely held as she began living this new reality, providing the optimum environment where she could allow her grief and loss to create new and unimagined insight into how to seize this life and find purpose and meaning despite unavoidable suffering and loss. Here is how we might apply components of stress and coping theory to map out Charlotte’s hypothesized risk and resilience factors:

|

A = Event (Little to no control) An event title is often a summary of a group of stressful events that might include the following:

|

|

B = Resources—Internal (Some control) |

B = Resources—External (Some control) |

|

|

|

C = Perspective (Sense of coherence; most control and most influential) Traumatic events in childhood are instrumental in shaping our internal mindsets, those conscious and unconscious beliefs influencing how we view self, other, and the world at large. Left unchallenged or responded to, our initial reactions lead to entrenched, negative worldviews. With a good-enough attachment community, our negative beliefs are softened or mitigated by positive, adaptive beliefs. It would be logical for Charlotte to vacillate between the following internal beliefs. Initially many of these neural networks would be expressed through attitudes and actions. But in moments of attunement, and over time as she gained the ability to put words to her deepest inner thoughts, she would gain the ability to experience what we would call neural integration between her implicit and explicit memory, and between competing states of mind and life realities. Such integration would allow her to eventually increase her capacity to hold the both/and with greater chance of reclaiming hope and joy. These competing beliefs might be as follows: |

|

Negative Neural Networks |

Positive Neural Networks |

|

Bad things can happen at any time; don’t trust that anything good will last. |

Bad things happen sometimes, but people who love you are there to help you through. |

|

Some bad things make life not worth living anymore. |

I can trust that when bad things happen, leaving me without hope that it will be OK, that this is to be expected. It will last for as long as it takes until I find my way through it. |

|

Moms (women) or dads (men) can be jerks, so don’t trust them. |

Moms and dads are not perfect and can mess things up sometimes, but they can learn from that to grow stronger and wiser. |

|

It was my fault that my parents didn’t get along; if I was a better child I could have helped my parents stay married. |

While it hurts that my parents couldn’t figure it out, their divorce had nothing to do with me. I did not cause it; I could not have prevented it. |

|

Don’t ever assume that relationships can or should be permanent. When love runs out, it just runs out. Don’t hope or expect anything more. |

Deep, lasting relationships are possible. But all of them take work—whether with siblings, friends, parents, or future spouses or my own kids someday. Sometimes we learn how to be better at relationships when we mess it up. My parents are learning how to be better at relationships. I can learn too. |

|

My mom’s body failed her and she died. Soon I am going to get sick and die too. Or, thank goodness I’m nothing like my mom, so I will never get cancer and die.

|

My mom’s illness and death are forcing me to realize that we don’t know what’s in store for our (my) future. But, I can take care of myself today as best I know how, and trust I will find a way through whatever life throws at me in the future. |

|

X = Level of Distress At any point along the way, whether adjusting to the reality of her parents’ divorce or her mother’s illness and death, Charlotte will be overwhelmed with a marginal ability to cope as well as have moments of peace and well-being. Some signs of her coping and distress may include the following: |

|

Signs of Distress |

Signs of Coping |

|

|

Not everyone is as fortunate as Charlotte—an odd statement given the severity of her traumas. And here lies a key point: A child’s true vulnerability may not be based on a particular event, but on a cumulative picture that reveals the relative safety of the developing child’s community, A child’s true vulnerability may not be based on a particular event, but on a cumulative picture that reveals the relative safety of the developing child’s community. as we will see in the story of Ben. Notice the negative neural networks messing with Charlotte’s heart and mind. These are universal challenges that she only has the capacity to make sense of and counterbalance due to the strength of her community. In the absence of attunement and mentoring, students are overrun and under the direct control of these negative neural networks. We will see this with Ben, but even more so with many of the students that give you the most concern.

Ben and the High-Risk Child

Ben was born in California, where he resided until age four, when his family moved to Central America to care for his aging grandparents. His family returned to California approximately two years ago. Midway through his sixth-grade year, Ben’s family was forced to move again to a small town outside of Dallas, Texas. This is the family’s fourth move since returning to the states. Ben speaks three languages: Spanish, a dialect of his native community in Peru, and English, although his English reading and writing skills are not yet to grade level. Ben presents as shy, quiet, and compliant. Initial testing revealed deficient grade-level skills in all subjects, and he was immediately placed in remedial ESL classes.

Ben’s parents have historically been loving and emotionally attentive to Ben’s needs. However, they are extremely stressed due to the family’s financial uncertainty, extended family responsibilities, and increasing sociopolitical animosity towards non-white immigrant communities. During their first trip to Ben’s new school, Ben and his mother were on high alert looking for signs that the school was welcoming and safe for immigrant children and their parents. Within the first minute on campus, they saw other students wearing clothing with political slogans congruent with antagonism to immigrants. Other red flags appeared based on questions asked and not asked, subtleties in body language, tone, and school culture. Both looked for a friendly face among a crowd of those in power, a person who could assure them that school was a safe and welcoming place for Ben.

Ben understands more than his teachers might think about the spoken and unspoken social class system in America. He knows his race, his accent, his name, and his unknown but assumed residency status make him a target. He’s learned to be adept at reading body language, decoding the deeper meaning underneath questions and comments from peers and adults. He lives in fear of being bullied by classmates (which he has experienced numerous times in his young life) and merely tolerated by school staff. He knows at first glance who is welcoming and who is disparaging of his presence.

Ben’s father now fights depression and uses alcohol in excess in the evenings in order to cope. Ben’s mother is increasingly anxious each time she or her husband leave home for fear of being detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); the chronic stress is impacting her physical health. With each move, the family loses its community (external) supports, and must start again finding others who understand their fight for survival and the dangers of living in a town or region hostile to immigrants, unaware of or unmoved by the war being waged against them in broad daylight.

At home, Ben worries for his parents. Have you ever flown on an airplane and endured intense air turbulence? A common coping mechanism is to gauge the seriousness of the situation according to the demeanor of the flight attendants. For Ben, his parents—life’s flight attendants—are scared; their level of stress, and their coping mechanisms suggest that the plane is going down! In preparation, his parents often rehearse with Ben and his siblings what to do if they are ever questioned or detained by ICE. And, most disturbing, they are instructed in what to do if Mom or Dad do not return home. The possibility of being ripped from their parents’ arms is a daily threat; Ben’s parents can assure him that they are doing everything possible to keep Ben and his three younger sisters safe, but they cannot lie. And their own demeanor suggests they are already being consumed by fear. Meanwhile, they need to equip Ben with tips for surviving if the worst comes true, and that includes teaching Ben how to look after his younger siblings.

Now, imagine tending to homework. Imagine carving out the physical and emotional energy (let alone time) to study for tomorrow’s test. Imagine how difficult it is to get a good night’s sleep when you fear the plane is about to crash. Meanwhile, Ben’s fight to cope with the chronic anxiety and fear is taxing numerous bodily systems. He is likely sleep deprived, unable to fully absorb all the nutrients from his diet regardless of its quality, and more susceptible to colds and other illnesses due to a taxed immune system.

Ben is an intelligent, loving child. He’s attentive, perceptive, and a quick learner. But he is living in a chronic state of just barely surviving, with threats to the safety of all family members at home and in the community, including school. His compliant, easy-going external demeanor belies what is likely going on inside of him—fear, hurt, anger, longing, and self-doubt as to his worth. While many children may be able to embrace the school day as respite from home-based stress, for Ben school is a microcosm of the larger social community that is the ultimate source of the family’s stress. School is jumping into the fire each day. It is neverending turbulence that may eventually bring the plane down.

Neurobiological Impact. We will begin applying this chapter’s concepts by first examining how Ben’s stressors might be taxing his innate stress response systems, as we described above. During Charlotte’s parents’ divorce and her mother’s illness and death, her sympathetic nervous system (SNS) was often on high alert, kicking in extra norepinephrine (the precursor to adrenaline) in moments of worry or fear. Her body knew that a long journey of coping was ahead, and released cortisol to help her along the way. But as she received comfort and assurance on a regular basis, her parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) was able to give rest to the SNS, releasing acetylcholine, easing bodily systems taxed in its efforts to help Charlotte cope. That process, combined with other mechanisms, helped signal the HPA Axis system to ease up on its need for extra cortisol.

Charlotte was in a season of stress and trauma; her grades suffered, and she experienced grief and existential disorientation. But her community supports enabled her to endure these challenges without her body betraying her, allowing her to engage in the hard work of making sense of and responding to life’s injustices.

Ben is a different story. Like Charlotte, he does not have abusive parents; he is loved by them, and knows his parents would lay down their lives for his well-being. But social and economic pressures have taken a toll on their health, and now he is functioning as a parent, worried for their social, emotional, and physical welfare. His parents are increasingly unable to provide him assurance. Home needs to be both a buffer and a training ground for dealing with life’s dangers; for Ben, it remains a training ground, but is no longer a buffer, as he watches his father increasingly consumed by alcohol and his mother increasingly immobilized by anxiety.

We can surmise that Ben’s autonomic nervous system (ANS) is not able to achieve that necessary balance between his SNS and PNS. Once the ANS can no longer self-regulate, our bodies begin to over- or under-produce the neurochemicals key to response (norepinephrine, cortisol, and others) and relaxation (acetylcholine, and others). Under- or over-production results in domino effects on the regulation of other neurochemicals, such as dopamine and serotonin, two of numerous neurochemicals dysregulated when we experience chronic stress (Scaer, 2005; Schore, 2003; Siegel, 2012; van der Kolk, 2014; Vermetten & Bremner, 2002).

Meanwhile, our long-term stress response system loses the ability to self-regulate, resulting in under- or over-production of cortisol, among other chemicals (Everly & Lating, 2012; Scaer, 2005; Vermetten & Bremner, 2002). The dysregulation of cortisol leads to a wide range of health issues, including the inability to extract nutrients from food, sleep dysregulation, a compromised immune system, and more.

All of us are predisposed to certain physical and mental health conditions. Some of us get migraines under stress, while others are more prone to intestinal problems. Some of us are more wired to experience anxiety or depression, whereas others may experience various symptoms congruent with mood or psychotic disorders. We do not know what Ben’s biological predispositions are, but we certainly will keep an eye out for the first telltale signs of emotional distress via symptoms of anxiety or depression. He is also physically at risk for frequent and perhaps chronic health conditions, all of which will undermine his ability to cognitively engage in school.

Co-occurring with fear is a deep longing for love, safety, and acceptance. Humans crave and need belonging. Without it, we panic, we doubt our worth, we fear for our survival. These are the ingredients of shame. And co-occurring with shame is deep hurt, the soul-crushing, agonizing pain of rejection. Adults come close to knowing this feeling upon the death of a spouse or loss of a relationship through divorce. Life can lose meaning or purpose. Adults are undone by these types of experiences; how much more are children injured? These experiences create entrenched worldviews (neural networks) that lead to a variety of self- and other-destructive behaviors for which we need to assess on an ongoing basis.

Complete Ben’s Assessment

Below is a partially filled-in map of an assessment of Ben’s risk and resilience factors. Using the concepts discussed thus far, how might you complete the map, similar to Charlotte’s map above?

|

A = Event (Little to no control). Name the event or issue and the specific types of stressors or traumatic events that accompany that event. Use Charlotte’s map as an example.

|

|

B = Resources—Internal |

B = Resources—External |

|

Internal (Some control)

|

External (Some control)

|

|

C = Perspective (Sense of coherence; most control and most influential) The formation of positive neural networks to stand in relationship with and mitigate the power of negative neural networks is key to coping, and key to a student being able to engage in the challenges of the school environment. This occurs within a community of care able to provide consistent attunement and mentoring throughout our first 18 years of life. Hypothesize what negative and corresponding positive neural networks might be competing for Ben’s attention, networks capturing his experience of and beliefs about self and other based on his life experiences. Refer to Charlotte’s map for an example, and Erikson’s chart (Figure 1) for common themes present in neural networks. |

|

Negative Neural Networks |

Positive Neural Networks |

|

I am flawed due to my ethnic, racial, and/or national identities. |

I am perfect as I am in all of my identities. |

|

Adults/parents are weak and hence untrustworthy. |

Adults/parents are amazing survivors even when overwhelmed by trauma. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X = Level of Distress Typically, we assess here-and-now signs of Ben’s coping and distress. Since we are hypothesizing this fictional student, include signs you might see in the future as well, given the nature of his current stressors, internal and external resources, and unintegrated neural networks, should they continue on their present course: |

|

Signs of Distress |

Signs of Coping |

|

|

Despite the severity of traumatic events experienced by Charlotte and Ben, neither of them may come across our radars as students displaying greater levels of externalized dysregulation often dominate our attention. But none of our students can afford to be placed on the back burner. The power of a trauma-informed approach is reimagining the education environment based on an integration of developmental and resilience theories, informed by advances in the neurobiology of stress and trauma. This universal approach ensures that no child is invisible.

Exercises

Classroom Application

In this chapter, we dug deeper into the formation of negative neural structures that, left unchecked, dominate our thinking, feeling, perceiving, and behavioral responses to the world. We also illustrated how our neural networks manifest in various signs of coping versus distress. Set aside about 30 or 40 minutes with a small group of peers currently working through this material to apply the concepts presented in this chapter in the exercise described below.

Using Worksheet B-1: Identifying Risk and Resilience in Appendix B, think about a student of concern. Begin by describing the student’s positive (including neutral) and negative behaviors in response to the demands of the school environment: everything from academic performance, timeliness, frustration tolerance, and capacity to focus, to social skills with peers and authority figures. List these observations in the X box, for signs of coping vs. distress. Next, go back up to Box A and identify known stressors impacting this student’s life. Include a hypothesis regarding the student’s access to safe, predictable, attuned, and mentoring home experiences that help or hinder the student’s stress response systems in returning to a state of calm, hence promoting homeostasis. Use Charlotte and Ben’s maps for ways to expand on describing the nature of the student’s challenges. Then, in Box B, identify internal coping resources that you observe the student displaying. What do you surmise are external resources that the student is or is not able to access?

Discerning a student’s internal perspectives (Box C) is often tough. The best way to hypothesize this is by decoding behavior, whether verbal, nonverbal, or actions. So, look back over this student’s signs of coping and distress. Then, stand back and ask what internal beliefs might be fueling the positive coping behaviors, and what beliefs might be behind the signs of distress. Next, look at the nature of the event(s) and what resources the student may or may not have access to, and ask what a student might nonverbally begin to feel or think about self and the world as a result. Use Erikson’s stage summary chart (Figure 2.1) for ways of putting words to internal positive and negative neural networks.

Next, in Appendix B, pull out Worksheet B-2: Domains of Neural Integration Assessment and Planning. Looking at your student’s behaviors across the coping-distress spectrum, identify the student’s strengths and struggles in the various domains being reflected in their school behavior. Later in your TISP readings, you will be able to return to this worksheet to identify classroom- or school-based activities to help strengthen domains needed to increase positive coping strategies. Be sure to use the charts in Figure 2.5 for a description of each domain.

A Look Forward

In Chapter 5, we will give you a conceptual road map regarding concrete ways to begin intervening on behalf of this child and your other students. In Section II you will be given the tools to develop a concrete action plan. For now, we have only two goals: to solidify your use of trauma-informed constructs to make sense of the complexity of what we are observing and increase your empathy for the profound role neural integration plays in our ability to function. That child who makes us want to quit our job is hurting, sending us messages in code. In Section II, we will unpack specific ways to stand in relationship with all of our students as attuned and mentoring attachment-focused educators.

Resources for Further Reading

- ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences) Connection. This resource-rich organization collates data from schools implementing trauma-informed practices.

- The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. A site rich with additional research articles and other resources.

- Trauma, Brain and Relationship: Helping Children Heal. This 30-minute documentary video describing attachment is available free online in segments.

- Bonding and Attachment in Maltreated Children: How You Can Help. Bruce Perry, M.D., Ph.D., provides tips on interacting with and nurturing children who may have insecure attachments.