9

“Every child needs to learn how to be responsible, to manage their thoughts and feelings, and to know they are loved and cared about.” —Fred Rogers

Desired Outcomes

This chapter identifies Phase II Coaching strategies for all educators, with special focus on classroom teachers. At the conclusion of this chapter, educators will be able to:

- Identify the goals of Coaching that inform the process of teaching students social-emotional and self-regulation skills

- Understand the interconnectedness of the five tasks of social-emotional learning, and its application to the integration of neural states

- Apply conceptual elements embedded in scaffolded social-emotional skill building

Key Concepts

This chapter presents the following key concepts:

- Scaffolding social-emotional skill building using Siegel’s states of neural integration and the five skills of social-emotional learning as a conceptual overlay

- Analyzing challenging student behavior to gain deeper understanding of student needs

- The significance of teaching and practicing social-emotional and self-regulation skills daily with our students

Chapter Overview

In this chapter we unpack Coaching by focusing on social-emotional and self-regulation skills our students need. We encourage you to view classroom management and/or student correction as an opportunity to coach the student by reinforcing social-emotional and self-regulation skills in the midst of student decisions or interactions that do not go as we hope. These skills are critical to student academic and social development, yet they are often overlooked. We continue to review and apply Siegel’s nine states of integration, providing additional practice and classroom application. We also dig into classroom interventions by giving you ideas and examples. This chapter will challenge you to critically analyze your own philosophical view of classroom management. Last, we provide a framework for viewing challenging student behavior to assist in deeper understanding of the needs of the students you serve.

Classroom management or student intervention is the number one area where teachers report needing more support or training. This chapter serves to show the connection between neural integration, self-regulation, and social-emotional learning as key strategies in classroom management.

Phase II: Coaching

You might be noticing that Phase I and II activities often blend into each other. As you are Connecting with students, you are moving them into self-regulation instruction or activities almost immediately. As relational trust and TI routines take hold, safety and stabilization activities are always working in tandem.

Phase II, Coaching, is all about helping a student achieve a sense of physiological and emotional stability, an inner sense of being grounded, of being in charge of their thoughts, feelings, physical sensations, and actions. It is the inner footing that ultimately helps us feel safe. We achieve this by first experiencing attunement—being seen and valued. Then, we need mentoring, consisting of being coached through various self-rescue practices again and again, followed by using them on our own as we are coached in the use of deepening self-regulation skills. It is a scaffolded and iterative process that builds over time as the student moves through various developmental challenges. Once a student is no longer at the mercy of their stress response system, the real work of growth—both academic engagement and accessing deeper levels of neural integration—begins to move at a faster pace.

Educators have long understood that social and emotional learning (SEL) skills are crucial to the student’s developmental process that enables access to executive functioning. SEL is commonly understood to consist of five core competencies (Collaborative for Academic, Social, & Emotional Learning, 2013). We define these competencies here as they relate to TISP:

Self-Awareness. Self-awareness refers to the ability to recognize and identify various internal need states as expressed in thoughts, feelings, and sensations, and with increasing practice, to identify how these internal states contribute to our behavioral choices. Using Siegel’s domains of neural integration (Figure 2.5), activities focusing on Vertical integration begin the self-awareness process. This is a precursor to learning additional skills such as self-soothing to tame heightened states of arousal, or unraveling distorted thoughts or beliefs to harness impulsive reactions. For example, an intense feeling of shame or anger, or an impassioned thought related to a misperceived indignation, may lead to an impulsive behavioral response, making matters worse for self or other. The more a student practices various strategies for increasing self-awareness, the more likely they are to choose self-management strategies.

Self-Management. Like self-awareness, self-management is a deepening ability requiring increased Vertical integration. As we identify internal cues, first we need to quickly respond with self-management techniques to calm the intensity of these thoughts and sensations. Most often, self-management employs self-soothing or self-rescue skills designed to calm our stress response systems. Self-management skills are then needed to increase our band of tolerance for the intensity of these experiences. This ability, to both defuse and tolerate the intensity of these inner stress responses, is a precursor to being able to resist reactions, set goals, delay gratification, and tolerate frustration, all ingredients to intentional action. As you can imagine, it is also a lifelong learning challenge consisting of multiple layers.

Eventually, effective self-management skills require greater access to executive functioning, as we need to learn how to focus on the internal thoughts and beliefs fueling the emotional and physical cues. This refers to the role perspective plays in our stress response and coping systems, as we reviewed in Section I. Until we learn how to start listening to our internal dialogues—the thought processes revealing our innermost wants, needs, fears, and beliefs—we will continue to be vulnerable to various types of dysregulated reactions to the social environment or our own immediate need states. Just like self-awareness, self-management requires educators to envision a scaffolded building of skills that occurs over the years.

Social Awareness. The heart of social awareness is being able to interpret events around us with some level of insight. We historically might say “accuracy,” but often we don’t really know the meaning underneath what we observe or experience until we inquire more. Social awareness also includes the ability to understand how our actions impact others.

Like the other skills, social awareness deepens over time. It is a complex skill requiring increasing integration of Horizontal and Memory neural networks, as our own unprocessed memories often are the source of our social misperceptions. Hence, it is learning not only to read emotions and connect current context to the logic of a communication sequence, but to do this against the backdrop of our own memories seizing our thoughts and feelings. This is a key process trauma-informed educators need to prepare for, as it may remain baffling that simple use of learned skills and techniques always needs practice and relearning.

Relationship Skills. Many educators find great utility in student management programs that offer concrete instructions and cues informing students of the socially appropriate behaviors expected of them in the school environment. Other schools opt for methods that teach guiding principles as the birth of prosocial behaviors; see Resources for Further Reading at the end of this chapter for links to sample programs. TISP reasons that the more a student is shown care and regard through consistent attunement and mentoring, the more the student is receptive to mentoring in how to treat others. Then, learning guiding principles and processes for fostering respect, safety, and community reinforces the relational values they are receiving from the adults around them. These challenges are a part of our Interpersonal neural networks that are often clouded by our own history of being on the receiving end of injustice, neglect, or abuse influencing our Narrative neural networks, among others.

Responsible Decision Making. As we experience greater levels of neural integration within all nine domains, we are better able to be fully Conscious. From this vantage point we are able to discern how to act in the moment and for what purpose as it relates to the past, present, and future. Here is where State, Temporal, and Transpirational neural networks add complexity to our discernment processes. The ability to tolerate our own ambiguity, to see a deeper meaning to life, and to want to be part of something beyond our immediate needs or reactions often directly or indirectly influences present decision making challenges. The more we are able to attune to these domains, the greater our ability to act with intentionality.

This too is a lifelong task. Moral developmental theories help us break this process down, understanding that we start from more simplistic schemas of right and wrong, moving to increased levels of empathy, to seeing larger moral principles in service to a commitment to principles of care and justice (Gilligan, 2009; Kraus, 2009; Wikipedia Contributors, 2018). Our students live in a culture where acting on impulse and at the expense of others is the norm. Daily we are teaching them to practice listening not only to their own internal cues, but to the needs of others around them, holding empathy for self and other as they discern how to act in the midst of being hurt, confused, scared, or angry.

As we examine how to scaffold self-management processes, take comfort in knowing that starting with the basics is necessary and appropriate, even while you commit yourself to seeing the end goal and developing further SEL activities to deepen neural network integration over time. The developmental nature of Coaching also reminds Districts, Schools, and Educators to create a way for classroom teachers to work together on SEL skill building with students they share in common, and to share about progress and concerns as students pass on to future grades.

Creating Self-Soothing and Self-Management Spaces

Many trauma-informed educators are discovering positive student engagement with various self-awareness and self-management techniques implemented within the classroom. How we employ those techniques can vary. A student can choose to use some techniques no matter where they are, such as diaphragmatic breathing (as long as they are still and not expected to talk). Other skills are practiced in large-group class activities.

A common technique is to create a space where a student can escape from the fray of the classroom, practice self-calming skills, and then return to class. These spaces are called calming centers, peace corners, break rooms, or whatever term a particular class might choose. Ideally these spaces are stocked with a variety of tools so a student can choose whatever method helps them engage in the self-awareness and management process. For them to be effective, students need to learn the skills, as well as have a clear structure for how, when, and for how long to use the space. Other techniques include affirming that a child’s desk or table space can be used as a calming center when needed—that sense of permission to go off task for a few minutes to give their brain a break as they engage in a calming activity geared to help them get back on track. The same structural rules apply here as well, such as not disturbing peers, setting a time limit, and perhaps giving the teacher a sign, not so much for permission but to affirm a sense of partnership; the teacher knows the student is struggling and a warm, acknowledging glance is anchoring, especially if more external assistance is needed. The actual techniques for increasing self-awareness and self-management are the student and teacher’s toolbox to create.

Trauma-informed classroom teachers who have used calming centers for any amount of time begin to learn what does and does not work. Search for their stories on YouTube, in trauma-informed school resources, at conferences, and education journals. And as you create your own classroom resources, add your experiences to the mix. In all new movements, we need to hear stories from front-line intrepid adventurers.

Chapter 9: Exercise 1

Siegel’s nine domains of neural integration are a useful template for identifying how various psychosocial learning moments in any given class are an opportunity for neural integration growth. Refer back to that list as you work through the following.

Scaffolding SEL skills is the content area requiring the most research and learning for trauma-informed educators. Trust that beginning SEL activities are commonly presented in many trauma-informed classroom application resources. However, to be able to assess your students’ broad and changing SEL coaching needs, you will need to understand the conceptual underpinnings and dig for additional resources. This activity is designed to help you get started.

Instructions:

- Using Figure 2.5 as a starting point, take each of the nine neural domains and identify the following:

- How would you explain this brain function to your students? Identify instructions, visuals, and examples that might be useful.

- Where in the student’s academic studies is this neural state already being explored or practiced? How might you help a student see this in a more clear way? For example, what stories or books do your students read, and how might you use a character’s narrative to illustrate a neural state?

- Imagine this neural state deepening over time. Perhaps the maturity occurs during your time with that student; in other places, it occurs over a span of a few academic years. Identify a social-emotional skill or practice you might use in an early, middle, and more mature stage of this state’s development.

- Share your ideas with those working through this process with you.

Elements of TISP Student Behavioral Interventions

In the second half of this chapter we focus explicitly on Phase II, Coaching, with an emphasis on elements of a trauma-informed educator response to students needing help when severely dysregulated. We are not providing a manual on how to implement a comprehensive student behavioral management system. Rather, we are providing you with basic trauma-informed tenets that should be embedded in whatever student management system you use, as they will influence how you respond to students needing help with regulation. To help orient you to the dispositions and concepts informing individual response to students, we start by identifying elements of the larger behavioral management system.

By student or behavioral management systems, we mean relational values, behavioral expectations, and the consequences of not living up to these community expectations. Relational values and behavioral expectations identify the code of conduct we expect from each other based on our context (a school, including various spaces within the school such as classrooms, restrooms, lunch areas, etc.), and the way we value one another and our own selves. For example, when we are in the library, the context might invite quieter hushed voices. But in outdoor recreation areas, we might be able to scream to our heart’s content. Our values regarding how to treat self and others dictate that each person will treat others respectfully, whether whispering or yelling. You are likely familiar with the role context plays in inviting some behaviors and not others, and most school-based relational value systems emphasize respect for self and other. The TISP ethos complements these existing principles.

How these relational values and behavioral expectations are taught is a key aspect of a student management system requiring trauma-informed review. An existing management program might emphasize a list of rules and scripts for being a respectful peer. Such systems are recognizing that many students are not embedded in communities where an emphasis is placed on such relational skill-building. A trauma-informed approach is not going to disagree with that observation or goal, but it will ask us to be aware that memorizing behavioral scripts does not integrate neural networks that build insight and empathy. Likewise, a system based on a token economy (a consequence or reward process) is also contrary to trauma-informed ethos and practice (Bloom, 2013; Cederlof, 2019; Flanagan, 2017; King, 2018; Pink, 2011). What you will notice below are not recommendations on what to avoid, rather on what relational elements to place front and center in whatever method you choose. Coaching, built upon the foundation of Connecting, recognizes that we are now reaching a student’s primary intrinsic need to be seen and valued, which naturally inspires goodwill to return those relational values toward others: the basics of empathy. And now your instructional scripts will be metabolized in ways that you ultimately intend.

TISP also emphasizes that struggle is developmentally expected and even necessary to learn. Therefore, adults are celebrating a student’s hard work, whether that means they met some benchmark standard for a social-emotional or academic task, or used some of the self-regulation skills offered to them, regardless of progress yet to occur. Hence, giving rewards to students who had an easier time reaching benchmark behavioral expectations and denying rewards to those who plowed through more neural network integration to make small gains is viewed as undermining the very values TISP is trying to teach. TISP also emphasizes that struggle is developmentally expected and necessary to learn. Therefore, adults are celebrating a student’s hard work, whether that means they met some benchmark standard for a social-emotional or academic task, or used some of the self-regulation skills offered to them, regardless of progress yet to occur. Hence, giving rewards to students who had an easier time reaching benchmark behavioral expectations and denying rewards to those who plowed through more neural network integration to make small gains is viewed as undermining the very values TISP is trying to teach. Such reward systems further shame and undermine hope and willingness to risk within students whose level of neural dysregulation increases their vulnerability to such shame. This leads many of these students to check out, and perhaps resent feeling marginalized. It is just one more reminder that they are different, inadequate, not valued or seen.

This issue illustrates the element of a student behavioral management system most influenced by TISP: examining the overt and covert values and meaning to our system of consequences, and what we may consider appropriate or timely consequences. For example, might our covert values really look and sound like punishment, rather than values of instruction and accountability? A zero-tolerance policy for certain behaviors might be enacted more out of anger toward the student than as a way to protect other students while the offending student has the chance to receive remedial help before returning to class. What you will observe in the scenarios below is an invitation to pick apart our internal mindset as we practice setting a boundary, and as we connect and coach a student back into a place of self-regulation prior to accountability.

Mindset

In my (Brenda’s) teacher preparation program, we were taught that there was a connection between good teaching and classroom management. The principle was simple: create engaging lessons and you won’t have classroom management challenges. It didn’t take me long to realize that engaging lessons are important, but my ability to manage the behaviors and emotions of middle and high school students rested on more than my lessons. But, as a new teacher, I struggled with self-doubt about whether I was good at my job. I viewed each classroom management issue as my own personal failure. It didn’t take me long to realize that engaging lessons are important, but my ability to manage the behaviors and emotions of middle and high school students rested on more than my lessons. But, as a new teacher, I struggled with self-doubt about whether I was good at my job. I viewed each classroom management issue as my own personal failure.

I know that I am not alone. As we mentioned in Section I, teachers have shared with us how they feel like they are not enough for their students; they feel a sense of helplessness as they struggle to curb poor choices amid growing student needs. When we teach TISP classes, we have our teachers create a list of the behaviors, actions, and attitudes they see in their classrooms that are concerning to them. No doubt your list would mirror what they have shared. And, we see the connection, even if it is subconscious, between student behavior and their perceived effectiveness as an educator. We hope that if this is you, you will set these thoughts aside, knowing that the best lesson in the world is still no match for a dysregulated brain.

Behavior, Interventions, and Discipline

At the beginning of Chapter 8, we shared the idea of green, yellow, and red lights to assess a student’s movement toward greater levels of dysregulation. This is a way for you to gauge where your students are and perhaps where they are heading if they are not able to access inner coping resources to return to a state of calm or focus. Students, through their behavior, are telling us what they need. We read their verbal and nonverbal messages and make decisions on how best to proceed. One teacher shared with us that she can physically see her kindergartener begin to emotionally escalate and then blow up. She learned quickly what she needs to watch for and strategies to help that child de-escalate to reduce the blow-ups or meltdowns.

As teachers, we have become adept at reading the room: absorbing verbal and nonverbal cues and pivoting when needed to keep students engaged in a lesson, or predicting when the debate in our classroom could erupt if we do not manage it carefully. But, we also need to teach social-emotional skills regularly and with intentionality. This is, by far, our best intervention strategy. Students cannot do what they have not learned to do.

Interventions

As presented earlier, the ability to self-regulate is key. Without this skill, it is difficult at best to tame emotions and focus on learning. As educators, we must hone the skills of perception and connection. By Connecting with our students, we gain understanding of their experiences and needs, and insight into what may cause them challenges in the classroom. This allows us to read our students throughout the day and adjust when necessary.

Think about a student in your classroom who you know struggles with self-regulation. Perhaps this is a student who can become frustrated easily or seems to have a quick temper. Our goal is to help our students practice self-regulation throughout the day by reading them and helping them increase their window of tolerance without flipping their lid.

Let’s consider what this could look like in the classroom. I (Brenda) had a student, Kristi, who had a very difficult time working in small groups. From the outside looking in, it appeared that everything and anyone could set her off without a lot of warning. When I planned an activity that required small groups, I would connect with Kristi to let her know what I had planned. I tried to always have the day’s agenda on the board so everyone knew that day’s plan for the class, but this was also to support Kristi and others who struggled with self-regulation.

Students could refer to the agenda on the board to determine how long I had planned for a particular activity or lesson. Once we moved into small group time, and I had established the goals and expectations, I would circle around to Kristi. With a warm smile I was able to connect with her, let her know I remembered this would make her uncomfortable, and remind her that she could take a break as needed. Kristi was able to refer back to the board to know how much longer the activity was planned for, and then could assess her needs during that time period.

Now, Kristi was a high school student, and we had worked on this over the course of the semester. I slowly increased the length of small group time to help her increase her window of tolerance. Kristi also knew that during small group time, I would be circling the room and checking in with her regularly. These check-ins could be as simple as making eye contact across the room—a quick reminder to her that I saw her, I knew this could challenge her, and she was safe. For me, this intervention became common practice, and I noticed it began to head off emotional outbursts from this student who started with a small window of tolerance.

Discipline

In Section I of this text, we began a discussion about discipline. As a quick refresh, in Chapter 4, we discussed impaired executive functioning and self-regulation ability in relationship to discipline systems. Systems that use punitive responses to student behaviors in an effort to help that child “learn” to make a different choice next time are ineffective, because they assume that the child knows of a more appropriate response and chose not to use it, and that the punishment will encourage a better choice next time (Ristuccia, 2013). We also pointed out that being trauma-informed does not mean giving children a free pass when they violate the norms of our classrooms or schools. So, how do you hold a student accountable under a trauma-informed model?

Let’s first consider the purpose for discipline. Refer back to your own Action Plan reflections when we invited Schools and Educators in Chapters 7 and 8 to prepare for a trauma-informed reflection on discipline policies. What is your own personal philosophy on discipline and student management in your own school or classroom? Does your philosophy align with the policies and procedures in your school? In a TISP model, we are prepared for our students to make mistakes and act in ways outside the norms we established. We seize this moment to reinforce what we have been teaching. This is what Phase II is all about: Coaching. This is our opportunity to recognize that unwanted behavior is a student calling for an unmet need to be addressed. This is our chance to reinforce our connection with that student. We do this by metaphorically catching them and holding them, by reminding them that we see them, we hear them, and we value them.

Let’s return to the story I (Brenda) shared in Chapter 1. My student teacher was in a third-grade class and had a student who would enter class in the mornings really angry, and rip up the worksheets he was handed. What I didn’t share in Chapter 1 is what my student teacher did in response. First, she created a calming space in the classroom, and then she introduced this space and taught the kids how to use it. She taught a series of mini-lessons on emotions and how to express them. She then made a habit of photocopying multiple copies of the worksheets, just in case! She immediately began greeting her students at the door each morning and welcoming them into the classroom. She worked hard to connect with her student who was particularly angry. And, when the inevitable blow-up came, she was ready…and so was the student. She smiled at him during his meltdown and empathically connected by saying she was sure he must have had a very difficult morning, but she was glad he was there. She invited him to the calming space, where he sat down and began using the tools he was taught to use. When she checked in on him a few minutes later and invited him back into the learning environment, she reminded him of the expectations. He joined without ripping up the worksheet.

She did what we are advocating. Support your students by encouraging them to self-soothe and self-regulate, using the strategies you have taught them. Then, debrief the situation and seek to understand what triggered the reaction or response you witnessed. Then, take that moment to coach them through ways they could have headed that blow-up off at the pass. And, don’t forget to use this moment to acknowledge any relational damage that occurred as a result, and what is needed to restore relationships with peers.

In a perfect situation, this can all be done in the classroom, in the midst of the blow-up or emotional outburst. However, there are times when this is just not the best course, or the blow-up is putting the child or others at risk of harm. Removing the child from the classroom to a safe space may be the best course of action, but the steps remain the same. In the midst of the upheaval, we are catching that student, making sure they know we are there, we are seeing them, and our connection has not splintered because of this situation. Once the child has returned to a state of calm, we can debrief and hold them accountable for what occurred.

Key Elements of the Educator’s Behavioral Management Mindset

- View dysregulated moments as an opportunity to connect and coach.

- Gently let the student know you are with them, and will work this through together.

- Have self-regulation tools/strategies familiar to the student at the ready.

- Practice ahead of time so that when needed, everyone goes into muscle memory.

- Affirm the student for working the process from dysregulated to regulated.

- Now engage in further dialogue regarding the student’s experience and needs (furthering the child’s neural integration), and any amends processes needed on the part of the student, class, or educator.

- Find a way to celebrate the student’s work or progress.

- As the behaviors continue to take hold, find ways for this student to be of encouragement to peers. We all can learn together.

Dysregulated Student Impact on Class and Teachers

Dysregulated students impact the entire class, including the teacher. We were in the middle of a trauma-informed training with a group of teachers when one teacher asked to debrief a situation she had just had in her classroom. The short version was that in the middle of recess, four students began fighting. It appeared to come out of nowhere: one moment things seemed fine, and the next she heard the scuffle. The teacher quickly called for help defusing the situation. One student, an innocent bystander, jumped in to help. He was physically larger and stronger and able to help restrain a couple of the students while help was coming from the office. All four students were removed from the playground and walked to the office, where the administration hoped to get to the bottom of this event. The teacher and the other students on the playground were left reeling from the incident. In fact, the teacher retelling the event was still dealing with the aftereffects of the adrenaline surge.

All students must feel safe in the classroom and school environment in order to learn. Students who are not suffering from unmitigated stress and trauma in ways their classmates are become victims of those classmates’ dysregulated. As the classroom becomes a place of unpredictability and chaos, learning is impacted and relationships get severed. All students must feel safe in the classroom and school environment in order to learn. Students who are not suffering from unmitigated stress and trauma in ways their classmates are become victims of those classmates’ dysregulated behavior. As the classroom becomes a place of unpredictability and chaos, learning is impacted and relationships get severed.

Student Interaction

When we provide training to schools and districts, we have our students complete an exercise titled “Student Interaction Analysis.” In this assignment, the participants are asked to reflect on a recent event or situation with a student that did not go well, and then analyze it using what they have learned thus far about trauma-informed practices. We introduced elements of this exercise with Ben and Charlotte in Chapters 2 and 3. The full exercise is included below. We invite you to work through this exercise.

Chapter 9: Exercise 2

Applying TISP Perceptual Conceptual Skills: Student Interaction Analysis

Identify a difficult interaction you had recently with a student. Using what you learned in Chapters 1-4, work through the following:

- Analyze the interaction according to the following:

- Describe the events exhibited in class. Using your perceptual skills, what was the sequence of events?

- Observe your student

- What did they say?

- What did their affect, tone, body stance, demeanor tell you?

- Internal Resources (Think back to Siegel’s domains of neural integration)

- What did the student do well?

- What strengths did they exude in that situation?

- What did the student struggle with?

- After observing your student’s behavior and hypothesizing on internal resources, begin hypothesizing on your student’s perspective and neural networks that are driving the behavior.

- First, what is known about the life experiences, circumstances, or traumas of this student?

- What external resources might this student have—or not have?

- Based on all of the above, identify the hypothesized perspective.

-

- List hypothesized negative neural networks.

- List hypothesized positive neural networks as we did in class.

-

- Based on all of the above, what might be additional logical learning and social challenges this student may face or exhibit?

- Retell the event: In light of Chapters 1-4 and any additional trauma-informed readings you may have done, offer a brief trauma-informed summary of what happened for or with this student.

- Final personal reflection.

- What was this exercise like for you?

- What was difficult?

- What was inspiring?

- Any final “aha” moments?

- What changes might you want to make, or are you already experimenting with or exploring as a result of learning about the domains of neural integration?

Below is an example from a teacher who completed this exercise.

Student Interaction Analysis

Clint, Middle School Teacher

During my third period class, a student who was not currently in the class entered in the middle of the lesson, got in the face of and started yelling at a student in the class. I walked over and, as calmly as possible, told the student that she needed to leave. I had to repeat myself several times, but eventually she did and I escorted her to the office. Her tone and demeanor very clearly indicated that she was operating out of her “downstairs” brain in “fight” mode. I later learned that she mistakenly believed the other student was spreading rumors about her. This student does a good job of advocating for herself and ensuring that her needs are met. However, she struggles with trusting others and has a strong desire to protect herself from being hurt in the best way she knows how.

This student has been in our school for about a year, having previously been in a challenging situation with some trauma. Her mother cares about her, but she probably rarely has had the benefit of an extended support network. A potential negative neural network might be something like “Others can’t be trusted, and if someone is trying to hurt me, it is up to me to protect myself.” A positive neural network might look something like “If someone is trying to hurt me, there are some trusted people I can go to for help.” Since building trust takes time, this student is going to continue to have struggles in threatening situations (real or perceived) until they are able to develop stable, trusting relationships.

A student of mine heard a rumor that another student was spreading rumors about her, which created an emotional and social threat. Since one of her dominant neural networks is that others can’t be trusted, she immediately assumed that the rumors were true and that it was up to her to do something about it. This stress response activated her limbic system and caused her to enter “fight” mode, come into my classroom, and proceed to yell and scream at the student alleged to have spread the rumor.

It was difficult to put myself into the place of the student. I can speculate about what is going on in her brain, but I don’t feel like I have enough knowledge yet to be very confident in my hypothesis. However, I do feel like I am able to recognize when a student is in fight-flight-freeze mode. This exercise has reinforced the importance of not going into fight-flight-freeze mode myself.

Putting It All Together

How do we apply what we have learned to the students in our care? We want to give you an opportunity to work through a mini case study from one of my (Brenda’s) student teachers, a real story of a student and the interaction. We invite you to read through and then consider the questions that follow.

Chapter 9: Exercise 3

Mini Case Study

Emily, Student Teacher

This year, I had a student in my seventh-grade Humanities classroom, Scott, who consistently showed up to school late. He shuffled into the room with his head down. Scott also tended to lash out at me whenever I called on him in class, telling me to “shut up” and “leave me alone,” and muttering unintelligibly under his breath. The other kids didn’t like sitting next to him because he “smelled weird and ate his boogers.” He seemed to realize that he was a persona non grata with his peers and would push his desk out of the row of desks to face the wall.

For months I greeted Scott by name each morning and told him I was happy to see him. He would nod at me, but not much else. Any remotely personal questions were rebuffed with a shrug and a glance at the door. His file in the counselor’s office didn’t reveal much other than a physical altercation with another student back in fifth grade. It wasn’t until parent-teacher conferences that I learned anything about Scott’s background. Instead of his mom or dad attending the meeting, his grandmother came. She sat down wearily and just said, “What did he do this time?”

She went on and on about what a horrible student Scott was and how he was “useless” at home, too. When asked about his family situation, Scott’s grandmother responded, “My son, Scott’s dad, was just as useless as Scott. Mama’s no good either.”

It turned out that Scott’s parents were addicted to meth. His father died of a meth overdose before his mother took off. Scott was left in the care of his grandparents, who did little to hide their disdain for Scott and his parents. Scott lived in an environment with people that consistently belittled him and devalued him.

After meeting Scott’s grandmother, I started asking Scott to help me with tasks around the room, like collecting papers and erasing whiteboards. We didn’t become “friendly,” but he seemed more at ease in the room and stopped pushing his desk against the wall.

One day in mid-January, Scott didn’t show up to class. This was unusual because Scott was never gone or even tardy. I was about to call down to the office to see if he was in the building, when my classroom door burst open. Scott stormed in and slammed into his seat. His cheeks were red and his hair stuck to the sweat on his forehead. Before I could ask what was wrong, he turned to the class and said, “They’re all talking about me behind my back. They’re all horrible. I shouldn’t have to be here.” I asked Scott if he wanted to step out into the hallway. He raised his voice. “Why should I be in trouble? I didn’t do anything wrong!” Scott was quickly losing his cool. He stood up and began pacing the room, telling me and anyone who would listen, “It’s just not fair!” Several students stood up and moved like they were going to try to calm Scott down, but I motioned them back to their seats. Scott slammed his fist into desks as he passed them.

Someone had slipped a note into Scott’s locker; it read, “Nobody likes you here. White trash.” It was a single note with some cruel words, but that was all it took to throw a wrench into Scott’s precarious emotional state. Nearly all of the important people in Scott’s life had made him feel that he was no good. Now, one of his peers confirmed these fears and it was too much.

I calmly invited Scott to step into the hallway or else I would have to call down to the office to have him removed. I paused and began breathing deeply. I exaggerated my breaths and soon I heard Scott trying to mimic me. After about 15 seconds, his breathing slowed and he pushed open the door to the hallway. Another teacher stepped in for a moment, and I followed him.

He was already crying, sitting against a locker. I sat down next to him and he told me what happened. We spoke for about five minutes and we talked about all the reasons why Scott did belong and all the ways he added to our community. He apologized as I walked him down to the office.

Questions to ponder:

- Given what was shared, are there items from the Key Elements of the Educator’s Behavioral Management Mindset evidenced in Emily’s interaction with Scott?

- How would you suggest welcoming Scott back into the classroom?

- How could Scott feel seen, heard, and valued?

Culture Shift

In the past, with students who present behavior and/or attendance problems, a common response of staff members has been to blame the family and create an adversarial relationship with parents. The call home was something like this: “Sorry to say that your child missed school, or disrespected a teacher, or got in a fight, and now needs to be punished.” As we have learned more about trauma and ACES, conversations with students and parents are less about punishment and more about finding solutions, creating space for change, and helping families connect with resources in the community. —Bruce, District Administrator

Teaching Social-Emotional Learning

As mentioned previously, we need to teach our students the social-emotional skills they need to be successful. These lessons can be taught at any point in the day and reinforced through your curriculum or through modeling them for your students. In my classes, I (Brenda) try to be intentional about modeling both social-emotional learning strategies. I teach in two- to four-hour blocks, which can be challenging. However, it is a great opportunity to build in mindfulness practices, breathing exercises, words of affirmation to peers, guided imagery, etc. I found that I needed and looked forward to these just as much as my students! And, with these built into the lesson plan, we could all relax, knowing a break was just moments away. Two of my students shared how they were teaching social-emotional learning and skills to their elementary students. The strategies they created in their classrooms with their mentors/cooperating teachers are below.

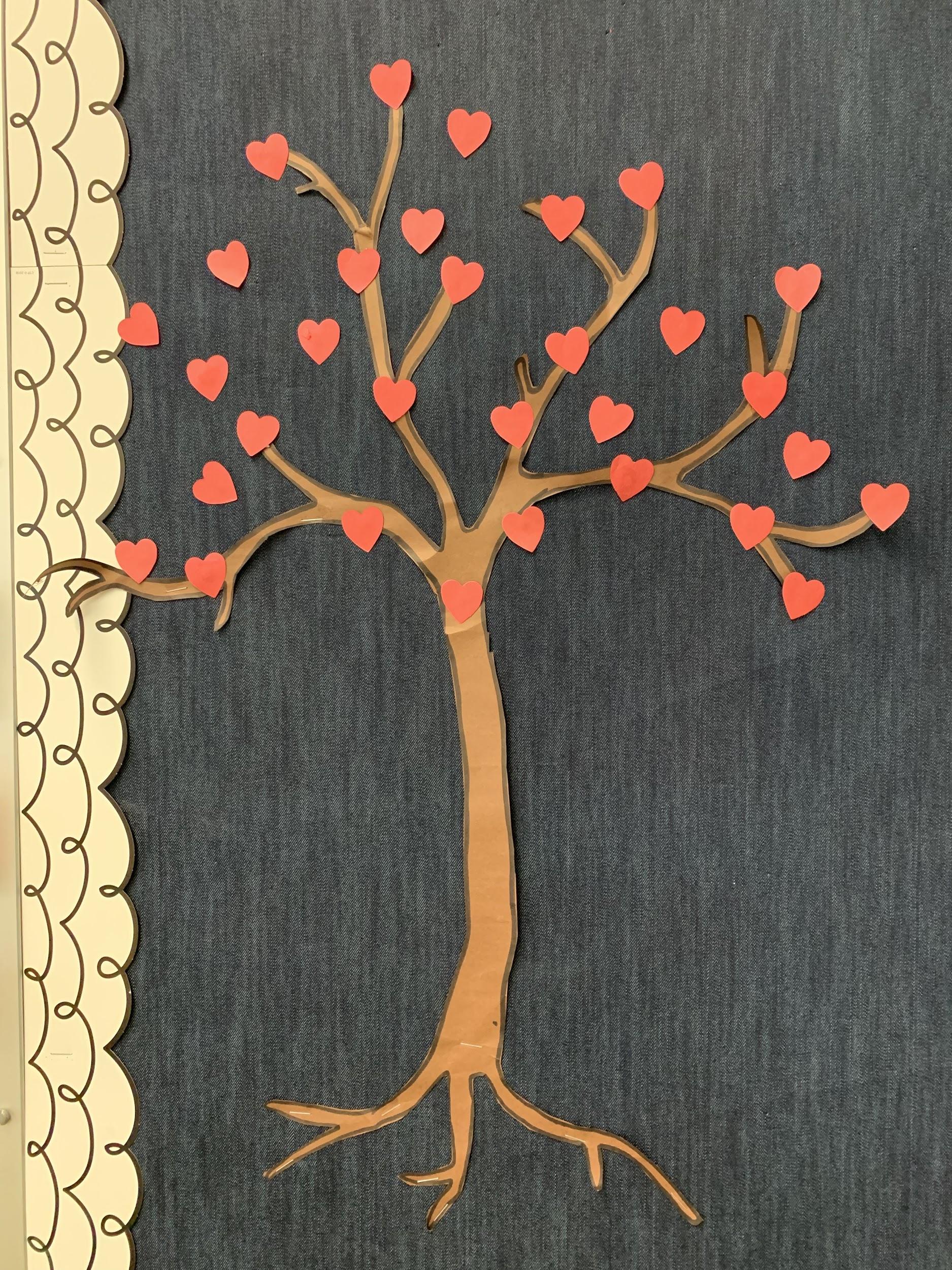

Kindness Tree Strategy

We begin with an example from an elementary classroom with first-grade students. In this class, the student teacher and her cooperating teacher noticed that the students were not being kind to their classmates in the ways they talked and interacted with them during the day. Developmentally, they saw their students as moving from an egocentric worldview to focusing on building relationships with others, including developing an awareness of the feelings and needs of individuals. They decided to create mini-lessons around kindness and create a kindness tree to support this development.

Clare, Student Teacher

In our kindergarten class, we began to notice an increase in the number of situations and language that wasn’t kind. We decided we wanted to focus our social-emotional learning on teaching kindness. Our goal was to teach our children what it means to be kind and how to show kindness to others both in our classroom and on the playground. To accomplish this, we chose an activity called the Kindness Tree, from Dr. Becky Bailey’s Conscious Discipline. We created a bulletin board and cut out a tree with many branches. We then created several mini-lessons to be taught over the course of the week. These lessons included definitions of kindness and examples of words and actions that were kind. We wanted to include a bit of science so we also showed a short child-friendly video of the effects that kindness has on the person who is being kind and the receiver of that kindness.

The first lesson was focused on defining kindness. We began by asking them a couple of questions: 1. What is kindness? 2. What can you do to show kindness? Last, students identified words that they could use to show kindness. Students were then asked to write down phrases that are kind that they would like to hear more of in the classroom. After the discussion, we identified one student each day to be our “kindness recorder.” Their job was to notice their classmates doing something kind and record that on a checklist. We also did this with our own checklist. During the day, we recorded what types of kindness were observed. At the end of the day we shared how many times they were kind during the course of the day. We then put hearts onto the kindness tree, one for each act of kindness, providing a visual representation of the ways in which they had shown kindness to their classmates.

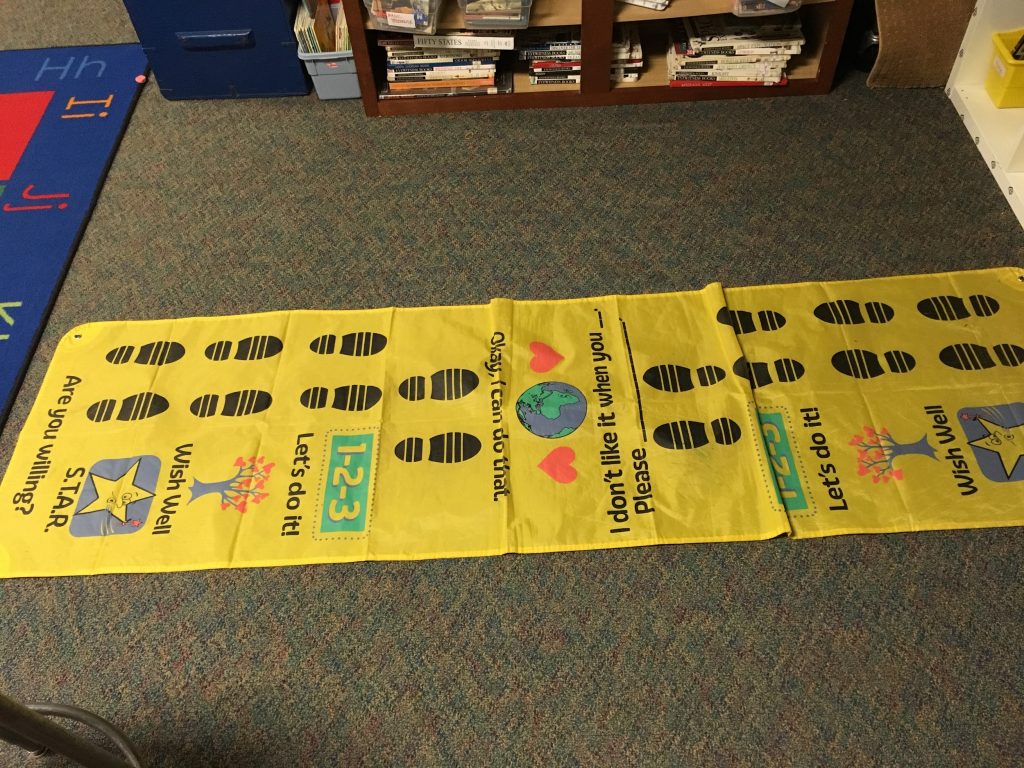

Problem-Solving Mat

This example demonstrates the significance of problem solving. How many times have we as teachers been frustrated by tattling? I know I often was frustrated by my students who expected me to jump in the middle of a situation, when I just wanted them to work it out! This is one way to teach students the value of relationships and how to repair them when something has happened to upset that relationship. And, it teaches them how to put language to what they are feeling and be empowered to address it.

Sky, Student Teacher

The problem-solving mat was implemented in November due to the number of kids who were tattling and the amount of teaching time we were losing because of it. The strategy was introduced to support social-emotional learning. Mini-lessons were created to discuss problem solving, a classroom culture of kindness, and the value of relationships with others.

The problem-solving mat has specific steps and sentence frames on it for the children to use in order to solve their problems amongst themselves. The mat provides a safe space for them to work out their issues instead of bringing the teacher into them. How it works: When students encounter a situation that is upsetting or frustrating in some way, they ask the person who upset them to go to the problem-solving mat. Students stand on each end of the mat and work through a specific protocol where each has the opportunity to speak and be heard. The student who was upset (victim) shares what occurred that upset them, using sentence frames like “I don’t like it when ____” and “Next time _____.” The person who upset them listens and responds. When both feel that their issue has been resolved, they shake hands and return to the learning environment.

The problem-solving mat helps to make the children more self-aware of what kinds of things set them off to the point where they need to use the mat. It also teaches them how to self-manage because they invite the other student themselves and take care of their own problems. They become more socially aware of what kinds of things are appropriate and what are not, through what makes them want to take kids to the problem-solving mat or why they are being taken there. They are able to decide together how they will handle the problem. Giving them the social-emotional skills they need to get past tattling is important so that they can start using their own little brains to solve their problems instead of being dependent on an adult.

Chapter 9: Exercise 4

Application to Your Classroom

While these examples above came from an elementary classroom, it would be simple to create a middle school and a high school version of these activities. Let’s pause for a moment and reflect on your classroom. Think about:

- What are the challenges in your classroom?

- What social-emotional skills do you need to teach?

- How can you plan for these throughout the year?

- What kind of visual reminders could you create to reinforce them?

- How will you Coach students when relationships are fractured?

Conceptual Application—Story from the Classroom

Doreen is an experienced elementary teacher who began working toward her certificate in TISP (George Fox University, 2019b). In our course on classroom management, we introduced Dr. Becky Bailey’s Conscious Discipline. This is her account of a recent interaction with a new student who has had difficulty with self-regulation and how she applied trauma-informed practices.

Kenny showed up three months into the school year; he marched alone into my room with matted hair and dirty clothes. I smiled and said (as all teachers do for all new students), “I’m glad you’re here. Let me show you our classroom.” He scowled at me and replied, “You should know, I was a big bad behavior problem at my last school.” My chest tightened and my brain flew to all of the new information I had been learning. “Our classroom is a team, and we want you to feel safe here.”

He looked warily at me, but followed me to our carpet for our morning team meeting. He sat tightly against me as I introduced him. I told the class that it was very scary for Kenny to come to a new school and asked if anyone could give him some encouragement. Because we had practiced giving meaningful compliments and encouragement to classmates, several students stepped up and told Kenny that he was welcome and they were there to help him. If only that was all that was needed to help a student in trauma!

I assigned him a buddy and we transitioned to writing. The minute students began moving from our circle to carpet spots, he began crawling around and growling. When his buddy showed him his spot, he put his new eraser into his mouth, chewed it up and began spitting on people. “Whoa,” I said. “What do you need right now?” He stared straight at me and said, “I’m addicted to erasers and I need them to keep going.” He tossed out a few swear words, then bolted and dove right for a tight space between a bookcase and a cart.

My students were wide-eyed, and I felt shaky. All I could think was, “I haven’t ever had enough learning or practice to know how to do this.” I had had some training and some practice. I had classes and a two-day conference under my belt about how we should respond to these kinds of situations. But now I was on call and didn’t exactly feel ready.

Dr. Becky Bailey had made us practice, more than once, how to “mirror” actions of a child in a trauma situation. She explained that curious children will look when you announce how they are acting to them and then act it out yourself. Then, because of the wonders of how our brain works, when and if you can make solid eye contact, the brain will by nature receive a shot of the all-powerful serotonin and dopamine and make a “feel-good” connection. So, I knelt down, and to his protruding backside, I said, “Your face looks sad, like this, and your body is all curled up like this.” He immediately turned, and I locked eyes with him and told him he was safe in our classroom and we loved having him there. He stayed watching, silent, but looking out instead of curled up and hiding.

You may wonder what the other 26 students were doing? They were quietly working on writing (you know how kids get really quiet when something dramatic is occurring) and looking at me with very worried eyes. “Second-graders,” I said, “I think Kenny needs our well-wishing.”

Another strategy from Conscious Discipline to deflect stress is to cross arms over the chest, breathe deep, and extend the arms, saying, “I wish you well.” Whether it affected Kenny at this point, I am unsure, but the others let out a big breath, crossed their little arms, and got to work. I could feel the level of intensity deflate a bit. Kenny stayed tucked away all morning, but he watched what the class was doing, and I circled around periodically and told him over and over, “We are glad you are here. This is a safe place.”

The afternoon was rough. He circled around the room and swore and told us that he hated our town. Every chance that I could, I looked at him in the eyes and repeated, “We are glad you are here. You are safe in this room.” Yes, it felt contrived, repetitive, and unlike any other strategy I’d ever had to use, but he looked at me each time and I could see and feel that a connection was being built. The afternoon was rough. He circled around the room and swore and told us that he hated our town. Every chance that I could, I looked at him in the eyes and repeated, “We are glad you are here. You are safe in this room.” Yes, it felt contrived, repetitive, and unlike any other strategy I’d ever had to use, but he looked at me each time and I could see and feel that a connection was being built.

This went on for a few weeks. Whenever I had enough patience and time, I told him we loved him and wanted him in our class. I also began telling him that every time he kicked, or spit, or yelled, or hit, those were actions that showed me he needed something, and I was going to help him find the words to tell me what he needed.

I began having him come in five minutes earlier than the other students so I could check in with him. One day, he walked in, threw his backpack across the room, and yelled. I knelt down and said, “What words can you tell me right now about what you need?” “I do not get to have any Christmas presents! And I’m grounded until I’m 18 years old, and nothing was my fault!” he screamed. “That must be scary and make you very sad,” I said. He collapsed against me and sobbed.

It was a turning point of sorts. There were still many incidents, but he began to trust me and we could talk about feelings, how to express needs, and which choices he could make that were healthy and helpful. After he had been in our classroom for three months, we were out at recess, and when I blew the whistle and kids lined up, Kenny came flying in and shoved two girls so he could be first in line. They were very angry and tried to tell him and me that it wasn’t fair. He denied doing it, even after I told him I was standing there and saw it all. “Our class decided together that no one is allowed to cut in line. It’s fair that you go to the end of the line.” He stomped and yelled, marched to the end of the line, entered the class, and threw himself into his tight corner and cried. After a few minutes, he came over and said, “I’m ready to work now.” I hugged him and told him I had noticed how he took some deep breaths, calmed himself, and came back to work all on his own! “Remember when you first came and it was so hard to do all of those things?” I asked him. He smiled. “Yeah, I was really bad, but now I feel proud and I think you are proud of me, too.” He stomped and yelled, marched to the end of the line, entered the class, and threw himself into his tight corner and cried. After a few minutes, he came over and said, “I’m ready to work now.” I hugged him and told him I had noticed how he took some deep breaths, calmed himself, and came back to work all on his own! “Remember when you first came and it was so hard to do all of those things?” I asked him. He smiled. “Yeah, I was really bad, but now I feel proud and I think you are proud of me, too.”

Doreen is a fantastic teacher, and it has been such a joy to watch her grow and develop into a competent trauma-informed educator. Like all teachers, Doreen will have good days and days where she is unsure if she practices the trauma-informed skills as best she could. However, Doreen is entering her classroom each day with new skills, new competencies, that allow her to connect, coach, and commence academic and social development of all students in her classroom.

A Look Forward

In this chapter we discussed self-regulation and how critical it is that we teach our students how to regulate their emotions. We also presented the importance of dissecting student behavior to uncover deeper needs so that we can create interventions to support our students. In Section III, we explore Phase III tasks to ensure that TISP is implemented and sustained in a manner supportive to the outcomes we envision are possible for each student regardless of the constraints that bind their academic and social-emotional engagement skills when they first enter our schools.

Resources for Further Reading

- The Whole Brain Child: 12 Revolutionary Strategies to Nurture Your Child’s Developing Mind, by Daniel J. Siegel and Tina Payne Bryson.

- Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain, by Daniel J. Siegel.

- Better Than Carrots or Sticks: Restorative Practices for Positive Classroom Management, by Dominique Smith, Douglas Fisher, and Nancy Frey.

- CASEL Guide. Social-emotional learning standards offered by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL).

- Conscious Discipline. Classroom management program by Dr. Becky Bailey.

- Education Lifeskills. Social-emotional middle school resources.

- Embrace Civility. Bully prevention resources.

- Huffington Post article “Child Discipline: It’s Time to Rethink Reward Systems.”

- Leader in Me Character Development. This organization focuses on the development of youth.

- Restorative Justice Practice Guidelines for Schools. National Association of Community and Restorative Justice.

- School-Connect High School. Social-emotional high school resources.

- Toolbox—Dovetail Learning. Social-emotional K-6 resources.