12

Rhetorical Analysis

CYNTHIA KIEFER

The purpose of this chapter is to guide you on a path to greater rhetorical awareness and analytic skill development. This chapter is about developing and refining your critical thinking, reading, writing, and analysis skills as you explore and critique the ideas of others through rhetorical analysis. The content and related exercises will deepen your knowledge of rhetoric and how to use it to support your own arguments.

In this chapter, you will not be writing arguments based on your own opinions and beliefs. In fact, you will be setting aside your perspective on the topics in the practice articles completely while you learn to apply your rhetorical knowledge to analyze the author’s skill in presenting their argument.

In section 2.1, “Understanding Rhetorical Analysis,” you will learn more about what rhetorical analysis is, how to use rhetorical appeals and the related types of evidence to support an argument or perspective, and how to use rhetorical appeals as lenses to critique an argument as effective, ineffective, or some combination of both. The rhetorical analysis processes and skills presented in this chapter will give you experience and knowledge you need to create and present an argument of your own effectively when you engage with the content and assignments.

Using the rhetorical knowledge and “moves” you learn in this chapter, you will write a rhetorical analysis composition and/or create a presentation demonstrating your skill at breaking down and evaluating the quality of a written editorial and/or a TEDTalk. In other words, you will compose an argument about the quality of another rhetor’s argument. However, you will not be writing about your own opinion on the topic!

By the end of this chapter, our goal is for you to feel like more of a rhetorical insider with the agency to exercise your critical literacies and achieve your rhetorical goals. When you complete this chapter, you will have the rhetorical knowledge, confidence, and skills to write your own effective and balanced academic argument with your audience in mind and to support it with well-researched, credible evidence, rhetorical appeals, and appropriate rhetorical language.

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, you will learn to:

- Define and identify key rhetorical concepts and terms (rhetorical appeals including kairos, pathos, logos, and ethos).

- Apply knowledge of the rhetorical appeals to use them as a filter for rhetorical analysis.

- Analyze the use of rhetorical language and syntax to convey speaker or writer’s tone and to support or reflect the argument.

- Engage in rhetorical discussions with peers.

- Apply critical reading strategies.

- Compose a rhetorical analysis paper and/or presentation of a TED talk.

- Apply feedback from peers, writing tutors, and/or instructors to rhetorical analysis drafts.

- Reflect upon your rhetorical growth and as a rhetorical insider.

In this section, you will learn how to conduct a rhetorical analysis, appeal by appeal. The content and practice in this section is core to your understanding of rhetorical appeals and how to use them to perform a rhetorical analysis. After you engage with this content and discuss it with peers, you will begin to see that “writing is a social and rhetorical activity” (Roozen in Adler-Kassner and Wardle 17). Whether you are face-to-face with an author, you are engaging with their ideas and arguments. Similarly, they support their arguments with the words and existing knowledge and evidence provided by those who preceded them. As you develop your rhetorical awareness and analytical skills, you will see that all communications are socially and rhetorically constructed, usually to influence, inform, or entertain and audience.

2.1.1 HOW TO PERFORM A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS

For many people, particularly those in the media, the term “rhetoric” has a largely negative connotation. A political commentator, for example, may say that a politician is using “empty rhetoric” or that what that politician says is “just a bunch of rhetoric.” What the commentator means is that the politician’s words are lacking substance, that the purpose of those words is more about manipulation rather than meaningfulness. However, this is a flawed definition, though quite common these days. As you learned in Chapter 1, rhetoric is more about clearly expressing substance, meaning, and one’s perspective while considering the audience’s wants, needs, and values. rather than avoiding them.

This section will clarify what rhetorical analysis means and will help you identify the basic elements of rhetorical analysis through explanation and example.

WHAT IS RHETORICAL ANALYSIS?

Simply defined, rhetoric is the art or method of communicating effectively to an audience, usually with the intention to persuade; thus, rhetorical analysis means analyzing how effectively a writer or speaker communicates her message or argument to the audience.

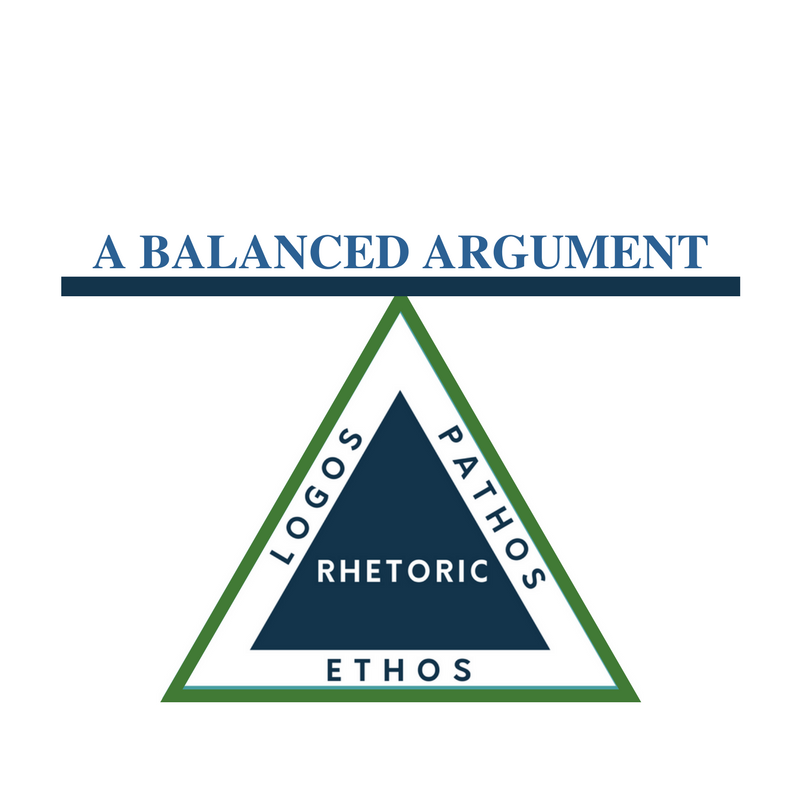

The ancient Greeks, namely Aristotle, developed rhetoric into an art form, which explains why much of the terminology that we use for rhetoric comes from Greek. The three major parts of effective communication, also called the Rhetorical Triangle (see Figures 2.1 and 2.3 below), are ethos, pathos, and logos, and they provide the foundation for a solid argument. As a reader and a listener, you must be able to recognize how writers and speakers depend upon these three rhetorical elements in their efforts to communicate. As a communicator yourself, you will benefit from the ability to see how others rely upon ethos, pathos, and logos so that you can apply what you learn from your observations to your own speaking and writing.

Rhetorical analysis can evaluate and analyze any type of communicator, whether that be a speaker, an artist, an advertiser, or a writer, but to simplify the language in this chapter, the term “writer” will represent the role of the communicator.

WHAT IS A RHETORICAL SITUATION?

Essentially, understanding a rhetorical situation means understanding the context of that situation. A rhetorical situation comprises a handful of key elements, which should be identified before attempting to analyze and evaluate the use of rhetorical appeals. These elements consist of the communicator in the situation (such as the writer), the issue at hand (the topic or problem being addressed), the purpose for addressing the issue, the medium of delivery (e.g.–speech, written text, a commercial), and the audience being addressed.

Answering the following questions will help you identify a rhetorical situation:

- Who is the communicator or writer?

- What is the issue that the writer (or speaker) is addressing?

- What is the main argument that the writer is making?

- What are the key supporting points, reasons, subclaims?

- On what assumptions (warrants) does the writer base the argument?

- What is the writer’s purpose for addressing this issue?

- To provoke, to attack, or to defend?

- To push toward or dissuade from certain action?

- To praise or to blame?

- To teach, to delight, or to persuade?

- What is the form in which the writer conveys it?

- What is the structure of the communication; how is it arranged?

- What oral or literary genre is it?

- What figures of speech (schemes and tropes) are used?

- What kind of style and tone is used and for what purpose?

- Does the form complement the content?

- What effect could the form have, and does this aid or hinder the author’s intention?

- Who is the audience?

- Who is the intended audience?

- What values does the audience hold that the author or speaker appeals to?

- Who have been or might be secondary audiences?

- If this is a work of fiction, what is the nature of the audience within the fiction?

Figure 2.1 A Balanced Argument

WHAT ARE THE BASIC ELEMENTS OF RHETORICAL ANALYSIS?

The Appeal to Ethos

Literally translated, ethos means “character.” In this case, it refers to the character of a writer or speaker, or more specifically, their credibility. The writer needs to establish credibility so that the audience will trust them and, thus, be more willing to engage with the argument. If a writer fails to establish a sufficient ethical appeal, then the audience will not take the writer’s argument seriously.

For example, if someone writes an article that is published in an academic journal, in a reputable newspaper or magazine, or on a credible website, those places of publication already imply a certain level of credibility. If the article is about a scientific issue and the writer is a scientist or has certain academic or professional credentials that relate to the article’s subject, that also will lend credibility to the writer. Finally, if that writer shows that he is knowledgeable about the subject by providing clear explanations of points and by presenting information in an honest and straightforward way that also helps to establish a writer’s credibility.

When evaluating a writer’s ethical appeal, ask the following questions:

Does the writer come across as reliable?

- Viewpoint is logically consistent throughout the text

- Does not use hyperbolic (exaggerated) language

- Has an even, objective tone (not malicious but also not sycophantic)

- Does not come across as subversive or manipulative

Does the writer come across as authoritative and knowledgeable?

- Explains concepts and ideas thoroughly

- Addresses any counter-arguments and successfully rebuts them

- Uses a sufficient number of relevant sources

- Shows an understanding of sources used

What kind of credentials or experience does the writer have?

- Look at byline or search for credible biographical info

- Identify any personal or professional experience mentioned in the text

- Where has this writer’s text been published?

Recognizing a Manipulative Appeal to Ethos

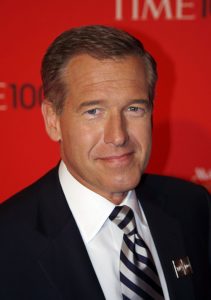

In a perfect world, everyone would tell the truth, and we could depend upon the credibility of speakers and authors. Unfortunately, that is not always the case. You would expect that news reporters would be objective and tell news stories based upon the facts; however, Janet Cooke, Stephen Glass, Jayson Blair, and Brian Williams all lost their jobs for plagiarizing or fabricating part of their news stories. Janet Cooke’s Pulitzer Prize was revoked after it was discovered that she made up “Jimmy,” an eight-year old heroin addict (Prince, 2010). Brian Williams was fired as anchor of the NBC Nightly News for exaggerating his role in the Iraq War.

Others have become infamous for claiming academic degrees that they didn’t earn as in the case of Marilee Jones. At the time of discovery, she was Dean of Admissions at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). After 28 years of employment, it was determined that she never graduated from college (Lewin, 2007). However, on her website (http://www.marileejones.com/blog/) she is still promoting herself as “a sought after speaker, consultant and author” and “one of the nation’s most experienced College Admissions Deans.”

Beyond lying about or elaborating upon their own credentials, authors may employ a number of tricks or fallacies to lure you to their point of view. Some of the more common techniques are described in the next chapter. When you recognize these fallacies, you should question the credibility of the speaker and the legitimacy of the argument. If you use these when making your own arguments, be aware that they may undermine or even destroy your credibility.

Exercise: Analyzing Ethos

Choose an article from the links provided below. Preview your chosen text, and then read through it, paying special attention to how the writer tries to establish an ethical appeal. Once you have finished reading, use the bullet points above to guide you in analyzing how effective the writer’s appeal to ethos is. If possible, work in small breakout groups to process the ethical appeals in through the criteria

“Why cancer is not a war, fight, or battle” by Xeni Jordan (https://tinyurl.com/y7m7bnnm) This article appears on CNN and is accessible. (MLA Citation: Jordan, Xeni. “Why cancer is not a war, fight, or battle.” CNN, 21 July 2017, www.cnn.com/2017/07/21/opinions/cancer-is-not-a-war-jardin-opinion/index.html.)

“Relax and Let Your Kids Indulge in TV” by Lisa Pryor (https://tinyurl.com/y88epytu) If you are locked out from accessing more free views of this article, your college library databases can provide access to the content. The text of this opinion piece can be found in the Major Dailies newspaper database by Proquest. (MLA Citation: Pryor, Lisa. “Relax, Let Your Kids Indulge in TV: [Op-Ed].” New York Times, Jul 04, 2017. )

“Why are we OK with disability drag in Hollywood?” by Danny Woodburn and Jay Ruderman (https://tinyurl.com/y964525k) If you are locked out from accessing more free views, your college library databases can provide access to the content. This text of this opinion piece can be found in the Major Dailies newspaper database by Proquest. Search for it by authors’ last names and a keyword or phrase from the title. (MLA Citation: Woodburn, Danny, and Jay Ruderman. “Why are we OK with Disability Drag?” Los Angeles Times, Jul 11, 2016.)

(Note: The article’s bibliographic information was added to the author’s original text.)

The Appeal to Logos

Literally translated, logos means “word.” In this case, it refers to information, or more specifically, the writer’s appeal to logic and reason. A successful logical appeal provides clearly organized information as well as evidence to support the overall argument. If one fails to establish a logical appeal, then the argument will lack both sense and substance.

For example, refer to the previous example of the politician’s speech writer to understand the importance of having a solid logical appeal. What if the writer had only included the story about 80-year-old Mary without providing any statistics, data, or concrete plans for how the politician proposed to protect Social Security benefits? Without any factual evidence for the proposed plan, the audience would not have been as likely to accept his proposal, and rightly so.

When evaluating a writer’s logical appeal, ask the following questions:

Does the writer organize their information clearly?

- Ideas are connected by transition words and phrases

- Choose the link for examples of common transitions (https://tinyurl.com/oftaj5g).

- Ideas have a clear and purposeful order

Does the writer provide evidence to back their claims?

- Specific examples

- Relevant source material

Does the writer use sources and data to back their claims rather than base the argument purely on emotion or opinion?

- Does the writer use concrete facts and figures, statistics, dates/times, specific names/titles, graphs/charts/tables?

- Are the sources that the writer uses credible?

- Where do the sources come from? (Who wrote/published them?)

- When were the sources published?

- Are the sources well-known, respected, and/or peer-reviewed (if applicable) publications?

Recognizing a Manipulative Appeal to Logos

Pay particular attention to numbers, statistics, findings, and quotes (expert testimony) used to support an argument. Be critical of the source and do your own investigation of the facts. Remember: What initially looks like a fact may not actually be one. Maybe you have heard or read that half of all marriages in America will end in divorce. It is so often discussed that we assume it must be true. Careful research will show that the original marriage study was flawed, and divorce rates in America have steadily declined since 1985 (Peck, 1993). If there is no scientific evidence, why do we continue to believe it? Part of the reason might be that it supports the common societal concern about the dissolution of the American family. Or, it could be because one divorce can affect a large number of people, leaving them with the idea that divorce is more prevalent than it is (the availability heuristic at work).

Fallacies that misuse appeals to logos or attempt to manipulate the logic of an argument are discussed in the next chapter in Critical Reading, Critical Writing: A Handbook to Understanding College Composition and Chapter 4 Understanding and Composing Researched Arguments in this book.

Exercise: Analyzing Logos

The debate about whether college athletes, namely male football and basketball players, should be paid salaries instead of awarded scholarships is one that regularly comes up when these players are in the throes of their respective athletic seasons, whether that’s football bowl games or March Madness. Proponents on each side of this issue have solid reasons, so we will examine four editorials that take opposing positions and critique the authors’ use of logos in their arguments. Because women’s sports are often left out of this discussion completely, yet are rising in popularity, we should become aware of perspectives regarding payments or compensation for college women’s sports athletes as well.

This exercise is designed to be completed in pairs, in person, in live online breakout groups, or through another method allowing for discussion.

Each pair will select one of the two sets to analyze.

Each partner within the pair will identify and analyze the use of logos within one of the two articles in their set.

Then each pair will discuss the perspective presented in their editorials and whether the authors used logos effectively or not.

Each partner in the pair should prepare a simple one-sentence claim about their author’s use of logos

Each pair will report out on their individual claims and provide a reflection on the activity, noting what they learned and any insights they gained from the activity.

Take note: Your aim in this rhetorical exercise is not to figure out where you stand on this issue. Rather, your aim is to evaluate how effectively the writers establish a logical appeal to support their positions, whether you agree with them or not. The goal of rhetorical analysis is to break down the effectiveness of a communicator’s or communication’s argument or point-of-view through the filter of logical appeals and use of rhetorical language.

Editorial Set 1 – Men’s College Sports

Editorial arguing against paying college athletes: Author is historian Taylor Branch. According to his bio on the Time site, Branch is “… a Pulitzer Prize winner [and] is the author most recently of The King Years: Historic Moments in the Civil Rights Movement.”

- “Why Telling the NCAA to Pay Players Is the Wrong Way to Help College Athletes.” Time [Online], 27 March 2019, time.com/5558498/ncaa-march-madness-pay-athletes/.

Editorial advocating for the payment of college (football) athletes: Author is journalist and opinion columnist Joe Nocera, according to his bio on Bloomberg.

- “Joe Nocera: College athletes should be paid.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 28 Sept, 2020, www.post-gazette.com/opinion/Op-Ed/2020/09/28/Joe-Nocera-College-athletes-should-be-paid/stories/202009280009#. (This editorial is based on the editorial Nocera wrote for Bloomberg on Sept. 22, 2020.)

Editorial Set 2 – Women’s College Sports

Editorial from a women’s sports perspective arguing against paying college athletes: Author is Morgan Chall, former Cornell University gymnast and NCAA level competitor.

- “Female college sports already get short shrift. Paying NCAA athletes will make it worse.” USA Today, 25 March 2021, www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2021/03/25/do-not-pay-college-ncaa-athletes-women-inequaity-column/6967702002/

Editorial advocating for the compensation of female athletes: Author is Patrick Hruby. According to his bio on Linked In, Hruby is “… a Washington, DC-based writer, editor, and journalist who specializes in the intersection of sports and social issues.”

- “Women’s Worth: How Female NCAA Athletes Will Profit in the New Era of NIL Rights.” Global Sports Matters, 12 March 2021, globalsportmatters.com/business/2021/03/12/womens-worth-how-female-ncaa-athletes-will-profit-in-the-new-era-of-nil-rights/. (Note to our fellow Arizonans: The About page at Global Sport Matters states that: “Global Sport Matters is the media enterprise brought to you by the Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University.”)

Step 1: Before reading the article, take a minute to preview the text, a critical reading skill explained in Chapter 1.

Step 2: Once you have a general idea of the article, read through it and pay attention to how the author organizes information and uses evidence, annotating or marking these instances when you see them.

Step 3: After reviewing your annotations, evaluate the organization of the article as well as the amount and types of evidence that you have identified by answering the following questions:

- Does the information progress logically throughout the article?

- Does the writer use transitions to link ideas?

- Do ideas in the article have a clear sense of order, or do they appear scattered and unfocused?

- Was the amount of evidence in the article proportionate to the size of the article?

- Was there too little of it, was there just enough, or was there an overload of evidence?

- Were the examples of evidence relevant to the writer’s argument?

- Were the examples clearly explained?

- Were sources cited or clearly referenced?

- Were the sources credible? How could you tell?

(Note: This practice exercise and the sources analyzed have been changed and/or modified from the original source.)

The Appeal to Kairos

Literally translated, means the “supreme moment.” In this case, it refers to appropriate timing, meaning when the writer presents certain parts of her argument as well as the overall timing of the subject matter itself. While not technically part of the Rhetorical Triangle, it is still an important principle for constructing an effective argument. If the writer fails to establish a strong Kairotic appeal, then the audience may become polarized, hostile, or may simply just lose interest.

If appropriate timing is not taken into consideration and a writer introduces a sensitive or important point too early or too late in a text, the impact of that point could be lost on the audience. For example, if the writer’s audience is strongly opposed to her view, and she begins the argument with a forceful thesis of why she is right and the opposition is wrong, how do you think that audience might respond?

In this instance, the writer may have just lost the ability to make any further appeals to her audience in two ways: first, by polarizing them, and second, by possibly elevating what was at first merely strong opposition to what would now be hostile opposition. A polarized or hostile audience will not be inclined to listen to the writer’s argument with an open mind or even to listen at all. On the other hand, the writer could have established a stronger appeal to Kairos by building up to that forceful thesis, maybe by providing some neutral points such as background information or by addressing some of the opposition’s views, rather than leading with why she is right and the audience is wrong.

Additionally, if a writer covers a topic or puts forth an argument about a subject that is currently a non-issue or has no relevance for the audience, then the audience will fail to engage because whatever the writer’s message happens to be, it won’t matter to anyone. For example, if a writer were to put forth the argument that women in the United States should have the right to vote, no one would care; that is a non-issue because women in the United States already have that right.

When evaluating a writer’s kairotic appeal, ask the following questions:

- Where does the writer establish their thesis of the argument in the text? Is it near the beginning, the middle, or the end? Is this placement of the thesis effective? Why or why not?

- Where in the text does the writer provide her strongest points of evidence? Does that location provide the most impact for those points?

- Is the issue that the writer raises relevant at this time, or is it something no one really cares about anymore or needs to know about anymore?

Exercise: Analyzing Kairos

In this exercise, you will analyze a visual representation of the appeal to Kairos. On the 26th of February 2015, a photo of a dress was posted to Twitter along with a question as to whether people thought it was one combination of colors versus another. Internet chaos ensued on social media because while some people saw the dress as black and blue, others saw it as white and gold. As the color debate surrounding the dress raged on, an ad agency in South Africa saw an opportunity to raise awareness about a far more serious subject: domestic abuse.

Step 1: Read this article (https://tinyurl.com/yctl8o5g) from CNN about how and why the photo of the dress went viral so that you will be better informed for the next step in this exercise:

Step 2: Watch the video (https://youtu.be/SLv0ZRPssTI, transcript here) from CNN that explains how, in partnership with The Salvation Army, the South African marketing agency created an ad that went viral.

Step 3: After watching the video, answer the following questions:

- Once the photo of the dress went viral, approximately how long after did the Salvation Army’s ad appear? Look at the dates on both the article and the video to get an idea of a time frame.

- How does the ad take advantage of the publicity surrounding the dress?

- Would the ad’s overall effectiveness change if it had come out later than it did?

- How late would have been too late to make an impact? Why?

STRIKING A BALANCE WITH RHETORICAL APPEALS

The foundations of rhetoric are interconnected in such a way that a writer needs to establish all of the rhetorical appeals to put forth an effective argument. If a writer lacks a pathetic appeal and only tries to establish a logical appeal, the audience will be unable to connect emotionally with the writer and, therefore, will care less about the overall argument. Likewise, if a writer lacks a logical appeal and tries to rely solely on subjective or emotionally driven examples, then the audience will not take the writer seriously because an argument based purely on opinion and emotion cannot hold up without facts and evidence and writer’s ethos to support it. If a writer’s argument lacks either the pathetic or logical appeal, not to mention the kairotic appeal, then the audience’s sense of writer’s internal ethos will suffer. All of the appeals must be sufficiently established for rhetors to communicate effectively with their audiences.

Key Takeaways

Understanding the Rhetorical Situation:

- Identify who the communicator is.

- Identify the issue at hand.

- Identify the communicator’s purpose.

- Identify the medium or method of communication.

- Identify who the audience is.

Identifying the Rhetorical Appeals:

- Ethos = the writer’s credibility (internal ethos) and the credibility of sources and quoted individuals (external ethos)

- Pathos = the writer’s emotional appeal to the audience

- Logos = the writer’s logical appeal to the audience

- Kairos = appropriate and relevant timing of subject matter

- In sum, effective communication is based on an understanding of the rhetorical situation and on a balance of the rhetorical appeals