Chapter 2: Communication, Perception, and Identity

Learning Objectives

- Define perception.

- Describe the three steps of the perception process.

- Recognize the roles that impressions and cultural influences play in the perception of others.

- Define self-concept and discuss how we develop our self-concept.

- Define self-presentation and discuss common self-presentation strategies.

- Identify outcomes and implications for self-presentation choices.

- Discuss strategies for improving perception of self and others.

Think back to the first day of classes. Did you plan ahead for what you were going to wear? Did you get the typical school supplies together? Did you try to find your classrooms ahead of time or look for the syllabus online? Did you look up your professors on an online professor evaluation site? Based on your answers to these questions, I could form an impression of who you are as a student. But would that perception be accurate? Would it match up with how you see yourself as a student? And perception, of course, is a two-way street. You also formed impressions about your professors based on their appearance, dress, organization, demeanor, and approachability. The impressions that both teacher and student make on the first day help set the tone for the rest of the semester.

As we go through our daily lives, we perceive all sorts of people and objects, and we often make sense of these perceptions by using previous experiences to help filter and organize the information we take in. Sometimes we encounter new or contradictory information that changes the way we think about a person, group, or object. The perceptions that we make of others and that others make of us affect how we communicate and act. In this chapter, we will learn about how we perceive others, how we perceive and present ourselves, and how we can improve our perceptions.

2.1 Perceiving Others

Are you a good judge of character? How quickly can you “size someone up?” Interestingly, research shows that many people are surprisingly accurate at predicting how an interaction with someone will unfold based on initial impressions. In politics, research has also been done on the ability of voters to make a judgment about a candidate’s competence after as little as 100 milliseconds of exposure to the politician’s face. Even more surprising is that people’s judgments of competence, after exposure to two candidates for senate elections, accurately predicted election outcomes (Ballew II & Todoroy, 2007). In short, after only minimal exposure to a candidate’s facial expressions, people made judgments about the person’s competence, and those candidates judged more competent were people who actually won elections! As you read this part of the chapter, keep in mind that these principles apply to how you perceive others and to how others perceive you. Just as others make impressions on us, we make impressions on others. The following sections describe the process of perception, as well as the external influences that help determine how we perceive others.

The Perception Process

Perception is the process of selecting, organizing, and interpreting information. Although perception is a largely cognitive and psychological process, how we perceive the people and objects around us affects our communication. We respond differently to an object or person that we perceive favorably than we do to something we find unfavorable. But how do we filter through the mass amounts of incoming information, organize it, and make meaning from what makes it through our perceptual filters and into our social realities?

Selecting Information

We take in information through all five of our senses, but our perceptual field (the world around us) includes so many stimuli that it is impossible for our brains to process and make sense of it all. As information comes in through our senses, various factors influence what actually continues through the perception process (Fiske & Taylor, 1991).

Selecting is the first part of the perception process, in which we focus our attention on certain incoming sensory information. Think about how, out of many other possible stimuli to pay attention to, you may hear a familiar voice in the hallway, see a pair of shoes you want to buy from across the store, or smell something cooking for dinner when you get home from work. We quickly cut through and push to the background all kinds of sights, smells, sounds, and other stimuli, but how do we decide what to select and what to leave out?

We tend to pay attention to information that is salient. Salience is the degree to which something attracts our attention in a particular context. The thing attracting our attention can be abstract, like a concept, or concrete, like an object. For example, a person’s identity as a Native American may become salient when they are protesting at the Columbus Day parade in Denver, Colorado. A bright flashlight shining in your face while camping at night is sure to be salient. We tend to find salient things that are visually or aurally stimulating, as well as things that meet our needs or interests (Fiske & Taylor, 1991).

Organizing Information

Organizing is the second part of the perception process, in which we sort and categorize information that we perceive based on innate and learned cognitive patterns. Three ways we sort things into patterns are by using proximity, similarity, and difference (Coren & Girgus, 1980). In terms of proximity, we tend to think that things that are close together go together. We also group things together based on similarity, tending to believe that similar-looking or similar-acting things belong together. Additionally, we organize information that we take in based on difference, assuming that the item that looks or acts different from the rest doesn’t belong with the group.

These strategies for organizing information are so common that they are built into how we teach our children basic skills and how we function in our daily lives. I’m sure we all had to look at pictures in grade school and determine which things went together and which thing didn’t belong. If you think of the literal act of organizing something, like your desk at home or work, we follow these same strategies. If you have a bunch of papers and mail on the top of your desk, you will likely sort and categorize those papers into separate piles. Your desk may have one drawer for pens, pencils, and other supplies and another drawer for files. In this case you are grouping items based on similarities and differences. You may also group things based on proximity, for example, by putting financial items like your checkbook, a calculator, and your pay stubs in one area so you can update your budget efficiently. In summary, we simplify information and look for patterns to help us more efficiently communicate and get through life.

Simplification and categorizing based on patterns isn’t necessarily a bad thing. In fact, without this capability we would likely not have the ability to speak, read, or engage in other complex cognitive/behavioral functions. Our brain innately categorizes and files information and experiences away for later retrieval, and different parts of the brain are responsible for different sensory experiences. In short, it is natural for things to group together in some ways. There are differences among people and looking for patterns helps us in many practical ways. However, the judgments we place on various patterns and categories are not natural; they are learned and culturally and contextually relative. Our perceptual patterns become unproductive and even unethical when the judgments we associate with certain patterns are based on stereotypical or prejudicial thinking.

Interpreting Information

Although selecting and organizing incoming stimuli happens very quickly, and sometimes without much conscious thought, interpretation can be a much more deliberate and conscious step in the perception process. Interpretation is the third part of the perception process, in which we assign meaning to our experiences.

One of the most important parts of the interpretation process is attribution, or the creation of an explanation for what is happening. In most interactions, we are constantly running an attribution script in our minds. Why did my neighbor slam the door when she saw me walking down the hall? Why is my partner being extra nice to me today? Why did my officemate miss our project team meeting this morning? In general, we seek to attribute the cause of others’ behaviors to internal or external factors. Internal attributions connect the cause of behaviors to personal aspects such as personality traits. External attributions connect the cause of behaviors to situational factors. Attributions are important to consider because our reactions to others’ behaviors are strongly influenced by the explanations we reach.

To demonstrate the difference between internal and external attributions, imagine that Gloria and Jerry are dating. One day, Jerry gets frustrated and raises his voice to Gloria. She may find that behavior more offensive and even consider breaking up with him if she attributes the cause of the blow up to his personality (an internal attribution). Conversely, Gloria may be more forgiving if she attributes the cause of his behavior to situational factors beyond Jerry’s control (an external attribution). This process of attribution is ongoing, and, as with many aspects of perception, we are sometimes aware of the attributions we make, and sometimes they are automatic and/or unconscious. Attribution has received much scholarly attention because it is in this part of the perception process that some of the most common perceptual errors or biases occur.

One of the most common perceptual errors is the fundamental attribution error, which refers to our tendency to explain others’ behaviors using internal rather than external attributions (Sillars, 1980). For example, many people get frustrated at parking enforcement officers, saying things like, “I got a parking ticket! I can’t believe those people. Why don’t they get a real job and stop ruining my life!” In this case, illegally parked individuals attribute the cause of their situation to the malevolence of the parking officer, essentially saying they got a ticket because the officer was a mean/bad person, which is an internal attribution. Individuals seem less likely to acknowledge that the officer was just doing their job (an external attribution) and the ticket was a result of the decision to park illegally.

Just as we tend to attribute others’ behaviors to internal rather than external causes, we do the same for ourselves, especially when our behaviors have led to something successful or positive. When our behaviors lead to failure or something negative, we tend to attribute the cause to external factors. This self-serving bias is a perceptual error through which we attribute the cause of our successes to internal personal factors while attributing our failures to external factors beyond our control. When we look at the fundamental attribution error and the self-serving bias together, we can see that we are likely to judge ourselves more favorably than another person, or at least less personally.

Influences on Perception

As we perceive others, we make impressions about their personality, likeability, attractiveness, and other characteristics. Although much of our impressions are personal, what forms them is sometimes based more on circumstances and external factors, rather than personal characteristics. All the information we take in isn’t treated equally. How important are first impressions? Does the last thing you notice about a person stick with you longer because it’s more recent? How do our cultural identities affect our perceptions? This section will help answer these questions.

First and Last Impressions

The old saying “You never get a second chance to make a good impression” points to the fact that first impressions matter. The brain is a predictive organ in that it wants to know, based on previous experiences and patterns, what to expect next, and first impressions function to fill this need, allowing us to determine how we will proceed with an interaction after only a quick assessment of the person with whom we are interacting (Hargie, 2011).

First impressions are enduring because of the primacy effect, which leads us to place more value on the first information we receive about a person. So if we interpret the first information we receive from or about a person as positive, then a positive first impression will form and influence how we respond to that person as the interaction continues. Likewise, negative interpretations of information can lead us to form negative first impressions. If you sit down at a restaurant and servers walk by for several minutes and no one greets you, then you will likely interpret that negatively and not have a good impression of your server when he finally shows up. This may lead you to be short with the server, which may lead him to not be as attentive as he normally would. At this point, a series of negative interactions has set into motion a cycle that will be very difficult to reverse and make positive.

The recency effect leads us to put more weight on the most recent impression we have of a person’s communication over earlier impressions. Even a positive first impression can be tarnished by a negative final impression. Imagine that a professor has maintained a relatively high level of credibility with you over the course of the semester. She made a good first impression by being organized, approachable, and interesting during the first days of class. The rest of the semester went fairly well with no major conflicts. However, during the last week of the term, she didn’t have final papers graded and ready to turn back by the time she said she would, which left you with some uncertainty about how well you needed to do on the final exam to earn an A in the class. When you did get your paper back, on the last day of class, you saw that your grade was much lower than you expected. If this happened to you, what would you write on the instructor evaluation? Because of the recency effect, many students would likely give a disproportionate amount of value to the professor’s actions in the final week of the semester, negatively skewing the evaluation, which is supposed to be reflective of the entire semester. Even though the professor only returned one assignment late, that fact is very recent in students’ minds and can overshadow the positive impression that formed many weeks earlier.

Cultural Influences

Our cultural identities affect our perceptions. Sometimes we are conscious of the effects and sometimes we are not. In either case, we tend to favor others who exhibit cultural traits that match up with our own. This tendency is so strong that it often leads us to assume that people we like are more similar to us than they actually are. Knowing more about how these forces influence our perceptions can help us become more aware of and competent about the impressions we form of others.

Race, gender, sexual orientation, class, ability, nationality, and age all affect the perceptions that we make. As we are socialized into various cultural identities, we internalize beliefs, attitudes, and values shared by others in our cultural group. Unless we are exposed to various cultural groups and learn how others perceive us and the world around them, we will likely have a narrow or naïve view of the world and assume that others see things the way we do. Exposing yourself to and experiencing cultural differences in perspective doesn’t mean that you have to change your worldview to match that of another cultural group. Instead, it may offer you a chance to better understand why and how your viewpoints were constructed the way they were.

As we have learned, perception starts with information that comes in through our senses. How we perceive even basic sensory information is influenced by our culture, as is illustrated in the following list:

-

How we “read” and perceive art differs from culture to culture. Photo by Vincent Tantardini on Unsplash. Sight. People in different cultures “read” art in different ways, differing in terms of where they start to look at an image and the types of information they perceive and process.

- Sound. “Atonal” music in some Asian cultures is considered displeasing by those who are not accustomed to it.

- Touch. In some cultures, it would be very offensive for a man to touch—even tap on the shoulder—a woman who isn’t a relative.

- Taste. Tastes for foods vary greatly around the world. “Stinky tofu,” which is a favorite snack of people in Taipei, Taiwan’s famous night market, would likely be very off-putting in terms of taste and smell to many foreign tourists.

- Smell. While US Americans spend considerable effort to mask natural body odor, which we typically find unpleasant, with soaps, sprays, and lotions, some other cultures would not find unpleasant or even notice what we consider “B.O.” Those same cultures may find an American’s “clean” (soapy, perfumed, deodorized) smell unpleasant.

As we discussed earlier in the chapter, our brain processes information by putting it into categories and looking for predictability and patterns. The previous examples have covered how we do this with sensory information, but we also do this with people. When we categorize people, we generally view them as “like us” or “not like us.” This simple us/them split affects subsequent interactions, including impressions and attributions. For example, we tend to view people we perceive to be like us as more trustworthy, friendly, and honest than people we perceive to be not like us (Brewer, 1999). We are also more likely to use internal attribution to explain negative behavior of people we perceive to be different from us. These tendencies can have negative consequences, and later we will discuss how forcing people into rigid categories leads to stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination.

2.2 Perceiving and Presenting Self

Just as our perception of others affects how we communicate, so does our perception of ourselves. But what influences our self-perception? How much of our self is a product of our own making and how much of it is constructed based on how others react to us? How do we present ourselves to others in ways that maintain our sense of self or challenge how others see us? We will begin to answer these questions in this part of the chapter, as we explore self-concept and self-presentation.

Self-Concept

If I said, “Tell me who you are,” your answers would be clues about your self-concept, or the overall idea of how a person views themself. Each person has an overall self-concept that might be encapsulated in a short list of overarching characteristics that they find important. But each person’s self-concept is also influenced by context, meaning we think differently about ourselves depending on the situation we are in. In some situations, personal characteristics, such as our abilities, personality, and other distinguishing features, will best describe who we are. You might consider yourself laid back, traditional, funny, open-minded, or driven, or you might label yourself a leader or a thrill-seeker. In other situations, our self-concept may be tied to group or cultural membership. For example, you might consider yourself a Southerner, a fraternity brother, or a member of the track team.

Our self-concept is also formed through our interactions with others and their reactions to us. The concept of the looking-glass self explains that we see ourselves reflected in other people’s reactions to us and then form our self-concept based on how we believe other people see us (Cooley, 1902). This reflective process of building our self-concept is based on what other people have actually said, such as “You’re a good listener,” and other people’s actions, such as coming to you for advice. These thoughts evoke emotional responses that feed into our self-concept. For example, you may think, “I’m glad that people can count on me to listen to their problems.”

We also develop our self-concept through comparisons to other people. Social comparison theory states that we describe and evaluate ourselves in terms of how we compare to others. This includes comparisons on characteristics like attractiveness, intelligence, athletic ability, and more. For example, you may judge yourself to be more intelligent than your brother or less athletic than your best friend, and these judgments are incorporated into your self-concept. This process of comparison and evaluation isn’t always a bad thing, but it can have negative consequences if our reference group isn’t appropriate. Reference groups are the groups we use for social comparison, and they typically change based on what we are evaluating. In terms of athletic ability, many people choose unreasonable reference groups with which to engage in social comparison. If a man wants to get into better shape and starts an exercise routine, he may be discouraged by his difficulty keeping up with the aerobics instructor or running partner and judge himself as inferior, which could negatively affect his self-concept. Using as a reference group people who have only recently started a fitness program but have shown progress could help maintain a more accurate and hopefully positive self-concept.

Social comparisons can affect our self-esteem, or the judgements and evaluations we make about our self-concept. If I again prompted you to “Tell me who you are,” and then asked you to evaluate (label as good/bad, positive/negative, desirable/undesirable) each of the things you listed about yourself, I would get clues about your self-esteem. Generally, some people are more likely to evaluate themselves positively, while others are more likely to evaluate themselves negatively (Brockner, 1988). More specifically, our self-esteem varies across our life span and across contexts.

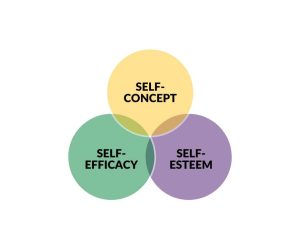

Self-esteem isn’t the only factor that contributes to our self-concept; perceptions about our competence also play a role in developing our sense of self. Self-efficacy refers to the judgments people make about their ability to perform a task within a specific context (Bandura, 1997). As you can see in Figure 2.1, judgments about our self-efficacy influence our self-esteem, which influences our self-concept.

Self-Presentation

How we perceive ourselves manifests in how we present ourselves to others. Self-presentation is the process of strategically concealing or revealing personal information in order to influence others’ perceptions (Human et al., 2012). We engage in this process daily and for different reasons. Although people occasionally intentionally deceive others in the process of self-presentation, in general we try to make a good impression while remaining authentic.

Numerous public examples demonstrate that we stand to lose quite a bit if we are caught intentionally misrepresenting ourselves. In 2022, New York congressman-elect George Santos faced public outrage after it was discovered that he had lied about his job experience and college education on the campaign trail. In 2012, the dean of admissions for the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology was dismissed after it became known that she had only attended one year of college and had falsely indicated that she had a bachelor’s and master’s degree (Webber & Korn, 2012). Such incidents clearly show that although people can get away with such false self-presentation for a while, the eventual consequences of being found out are dire. As communicators, we sometimes engage in more subtle forms of inauthentic self-presentation. For example, a person may state or imply that they know more about a subject or situation than they actually do in order to seem smart or “in the loop.” During a speech, a speaker could work on polished and competent delivery to distract from a lack of substantive content. These cases of strategic self-presentation may not ever be found out, but communicators should still avoid them as they do not live up to the standards of ethical communication.

In general, we strive to present a public image that matches up with our self-concept, but we can also use self-presentation strategies to enhance our self-concept (Hargie, 2011). When we present ourselves in order to evoke a positive evaluative response, we are engaging in self-enhancement. In the pursuit of self-enhancement, a person might try to be as appealing as possible in a particular area or with a particular person to gain feedback that will enhance one’s self-esteem. For example, a singer might train and practice for weeks before singing in front of a well-respected vocal coach but not invest as much effort in preparing to sing in front of her friends. Although positive feedback from her friends could be beneficial, positive feedback from an experienced singer could significantly enhance her self-concept. Self-enhancement can be productive and achieved competently, or it can be used inappropriately. Using self-enhancement behaviors just to gain the approval of others or out of self-centeredness may lead people to communicate in ways that are perceived as phony or overbearing and end up making an unfavorable impression (Sosik et al., 2002).

2.3 Improving Perception

So far, we have learned about how we perceive others and ourselves. Now we will turn to a discussion of how to improve our perception. Our self-perception can be improved by becoming aware of self-fulfilling prophecies and by engaging in supportive interpersonal relationships. How we perceive others can be improved by becoming aware of stereotypes and prejudice and engaging in perception checking.

Improving Self-Perception

Our self-perceptions can and do change. Recall that we have an overall self-concept and self-esteem that are relatively stable, and we also have context-specific self-perceptions. Context-specific self-perceptions vary depending on the person with whom we are interacting, our emotional state, and the subject matter being discussed. Becoming aware of the process of self-perception and the various components of our self-concept (which you have already started to do by studying this chapter) will help you understand and improve your self-perceptions.

Since self-concept and self-esteem are so subjective and personal, it would be inaccurate to say that someone’s self-concept is “right” or “wrong.” Instead, we can identify negative and positive aspects of self-perceptions as well as discuss common barriers to forming accurate and positive self-perceptions. We can also identify common patterns that people experience that interfere with their ability to monitor, understand, and change their self-perceptions. Changing your overall self-concept or self-esteem is not an easy task given that these are overall reflections on who we are and how we judge ourselves that are constructed over many interactions. A variety of life-changing events can relatively quickly alter our self-perceptions. Think of how your view of self changed when you moved from high school to college. Similarly, other people’s self-perceptions likely change when they enter into a committed relationship, have a child, make a geographic move, or start a new job.

Aside from experiencing life-changing events, we can make slower changes to our self-perceptions with concerted efforts aimed at becoming more competent communicators through self-monitoring and reflection. Let’s now discuss some suggestions to help avoid common barriers to accurate and positive self-perceptions and patterns of behavior that perpetuate negative self-perception cycles.

Beware of Self-Fulfilling Prophecies

Self-fulfilling prophecies are thought and action patterns in which a person’s false belief triggers a behavior that makes the initial false belief actually or seemingly come true (Guyll et al., 2010). For example, let’s say a student’s biology lab instructor is a Chinese person who speaks English as a second language. The student falsely believes that the instructor will not be a good teacher because he speaks English with an accent. Because of this belief, the student doesn’t attend class regularly and doesn’t listen actively when she does attend. Because of these behaviors, the student fails the biology lab, which then reinforces her original belief that the instructor wasn’t a good teacher.

Although the concept of self-fulfilling prophecies was originally developed to be applied to social inequality and discrimination, it has since been applied in many other contexts, including interpersonal communication. This research has found that some people are chronically insecure, meaning they are very concerned about being accepted by others but constantly feel that other people will dislike them. This can manifest in relational insecurity, which is again based on feelings of inferiority resulting from social comparison with others perceived to be more secure and superior. Such people often end up reinforcing their belief that others will dislike them because of the behaviors triggered by their irrational belief.

Take the following scenario as an example: An insecure person assumes that his date will not like him. During the date he doesn’t engage in much conversation, discloses negative information about himself, and exhibits anxious behaviors. Because of these behaviors, his date forms a negative impression and suggests they not see each other again, reinforcing his original belief that the date wouldn’t like him. The example shows how a pattern of thinking can lead to a pattern of behavior that reinforces the thinking, and so on. Luckily, experimental research shows that self-affirmation techniques can be successfully used to intervene in such self-fulfilling prophecies. Thinking positive thoughts and focusing on personality strengths can stop this negative cycle of thinking and has been shown to have positive effects on academic performance, weight loss, and interpersonal relationships (Stinston et al., 2011).

Create and Maintain Supportive Interpersonal Relationships

Photo by nappy from Pexels.

Aside from giving yourself affirming messages to help with self-perception, it is important to find interpersonal support. Although most people have at least some supportive relationships, many people also have people in their lives who range from negative to toxic. When people find themselves in negative relational cycles, whether it is with friends, family, or romantic partners, it is difficult to break out of those cycles. But we can all make choices to be around people who will help us be who we want to be and not be around people who hinder our self-progress. This notion can also be taken to the extreme, however. It would not be wise to surround yourself with people who only validate you and do not constructively challenge you, because this too could lead to distorted self-perceptions.

Overcoming Barriers to Perceiving Others

There are many barriers that prevent us from competently perceiving others. While some are more difficult to overcome than others, they can all be addressed by raising our awareness of the influences around us and committing to monitoring, reflecting on, and changing some of our communication habits.

Beware of Stereotypes and Prejudice

Stereotypes are sets of beliefs that we develop about groups, which we then apply to individuals from that group. Stereotypes are organizing patterns that are taken too far, as they reduce and ignore a person’s individuality and the diversity present within a larger group of people. Stereotypes can be based on cultural identities, physical appearance, behavior, speech, beliefs, and values, among other things, and are often caused by a lack of information about the target person or group (Guyll et al., 2010). Stereotypes can be positive, negative, or neutral, but all run the risk of lowering the quality of our communication.

While the negative effects of stereotypes are pretty straightforward in that they devalue people and prevent us from adapting and revising our schemata, positive stereotypes also have negative consequences. For example, the “model minority” stereotype has been applied to some Asian cultures in the United States. Seemingly positive stereotypes of Asian Americans as hardworking, intelligent, and willing to adapt to “mainstream” culture are not always received as positive and can lead some people within these communities to feel objectified, ignored, or overlooked.

Stereotypes can also lead to double standards that point to larger cultural and social inequalities. There are many more words to describe a sexually active woman than a man, and the words used for women are disproportionately negative, while those used for men are more positive. Since stereotypes are generally based on a lack of information, we must take it upon ourselves to gain exposure to new kinds of information and people, which will likely require us to get out of our comfort zones. When we do meet people, we should base the impressions we make on describable behavior rather than inferred or secondhand information. When stereotypes negatively influence our overall feelings and attitudes about a person or group, prejudiced thinking results.

Prejudice is negative feelings or attitudes toward people based on their identity or identities. Prejudice can have individual or widespread negative effects. At the individual level, a hiring manager may not hire a young man with a physical disability (even though that would be illegal if it were the only reason), which negatively affects that one man. However, if pervasive cultural thinking that people with physical disabilities are mentally deficient leads hiring managers all over the country to make similar decisions, then the prejudice has become a social injustice.

Engage in Perception Checking

Perception checking is a strategy to help us monitor our reactions to and perceptions about people and communication. There are some internal and external strategies we can use to engage in perception checking. In terms of internal strategies, review the various influences on perception that we have learned about in this chapter and always be willing to ask yourself, “What is influencing the perceptions I am making right now?” Even being aware of what influences are acting on our perceptions makes us more aware of what is happening in the perception process. In terms of external strategies, we can use other people to help verify our perceptions. The cautionary adage “Things aren’t always as they appear” is useful when evaluating your own perceptions. Sometimes it’s a good idea to bounce your thoughts off someone, especially if the perceptions relate to some high-stakes situation.

Key Concepts: Perception Checking

Perception checking helps us slow down perception and communication processes and allows us to have more control over both. Perception checking involves being able to describe what is happening in a given situation, provide multiple interpretations of events or behaviors, and ask yourself and others questions for clarification. Some of this process happens inside our heads, and some happens through interaction. Let’s take an interpersonal conflict as an example.

Stefano and Patrick are roommates. Stefano is in the living room playing a video game when he sees Patrick walk through the room with his suitcase and walk out the front door. Since Patrick didn’t say or wave good-bye, Stefano has to make sense of this encounter, and perception checking can help him do that. First, he needs to try to describe (not evaluate yet) what just happened. This can be done by asking yourself, “What is going on?” In this case, Patrick left without speaking or waving good-bye. Next, Stefano needs to think of some possible interpretations of what just happened. One interpretation could be that Patrick is mad about something (at him or someone else). Another could be that he was in a hurry and simply forgot, or that he didn’t want to interrupt the video game. In this step of perception checking, it is good to be aware of the attributions you are making. You might try to determine if you are overattributing internal or external causes. Last, you will want to verify and clarify. So Stefano might ask a mutual friend if she knows what might be bothering Patrick or going on in his life that made him leave so suddenly. Or he may also just want to call, text, or speak to Patrick. During this step, it’s important to be aware of punctuation. Even though Stefano has already been thinking about this incident, and is experiencing some conflict, Patrick may have no idea that his actions caused Stefano to worry. If Stefano texts and asks why he’s mad (which wouldn’t be a good idea because it’s an assumption) Patrick may become defensive, which could escalate the conflict. Stefano could just describe the behavior (without judging Patrick) and ask for clarification by saying, “When you left today you didn’t say bye or let me know where you were going. I just wanted to check to see if things are OK.”

The steps of perception checking as described in the previous scenario are as follows:

- Step 1: Describe the behavior or situation without evaluating or judging it.

- Step 2: Think of some possible interpretations of the behavior, being aware of attributions and other influences on the perception process.

- Step 3: Verify what happened and ask for clarification from the other person’s perspective. Be aware of punctuation, since the other person likely experienced the event differently than you.

Discussion Questions:

- Give an example of how perception checking might be useful to you in professional, personal, and civic contexts.

- Which step of perception checking do you think is most challenging and why?

References

Ballew, II, C. C., & Todorov, A. (2007). Predicting political elections from rapid and unreflective face judgments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(46), 17948–17953. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0705435104

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman.

Brewer, M. B. (1999). The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love or outgroup hate? Journal of Social Issues, 55(3), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758009376031

Brockner, J. (1988). Self-esteem at work. Lexington Books.

Cooley, C. (1902). Human nature and the social order. Scribner.

Coren, S., & Girgus, J. S. (1980). Principles of perceptual organization and spatial distortion: The gestalt illusions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 6(3), 404–412. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.6.3.404

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social cognition (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill.

Guyll, M., Madon, S., Prieto, L., & Scherr, K. C. (2010). The potential roles of self-fulfilling prophecies, stigma consciousness, and stereotype threat in linking Latino/a ethnicity and educational outcomes. Social Issues, 66(1), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01636.x

Hargie, O. (2011). Skilled interpersonal interaction: Research, theory, and practice. Routledge.

Human, L. J., Biesanz, J. C., Parisotto, K. L., & Dunn, E. W. (2012). Your best self helps reveal your true self: Positive self-presentation leads to more accurate personality impressions. Social Psychological and Personality Sciences, 3(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611407689.

Sillars, A. L. (1980). Attributions and communication in roommate conflicts. Communication Monographs, 47(3), 180–200. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1080/03637758009376031

Sosik, J. J., Avolio, B. J., & Jung, D. I. (2002). Beneath the mask: Examining the relationship of self-presentation attributes and impression management to charismatic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(3), 217–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00102-9

Stinson, D. A., Logel, C., Shepherd, S., & Zanna, M. P. (2011). Rewriting the self-fulfilling prophecy of social rejection: Self-affirmation improves relational security behavior up to 2 months later. Psychological Science, 20(10), 1145–1149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611417725

Webber, L., & Korn, M. (2012, May 7). Yahoo’s CEO among many notable resume flaps. Wall Street Journal Blogs. http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2012/05/07/yahoos-ceo-among-many-notable-resume-flaps

Credits

Chapter 2 was adapted, remixed, and curated from Chapter 2 of Communication in the Real World: An Introduction to Communication Studies, a work produced and distributed under a CC BY-NC-SA license in 2013 by a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution.