Chapter 6: Interpersonal Communication

Learning Objectives

- Define interpersonal communication.

- Discuss the functional and cultural aspects of interpersonal communication.

- Describe stages of relational interaction.

- Explain communication theories related to relationships coming together and coming apart.

- Identify patterns and triggers of interpersonal conflict.

- Compare and contrast the five styles of interpersonal conflict management.

- Apply connections between relevant interpersonal communication theory and practice.

Interpersonal communication has many implications for us in the real world. Did you know that interpersonal communication played an important role in human development? Early humans who lived in groups, rather than alone, were more likely to survive, which meant that those with the capability to develop interpersonal bonds were more likely to pass these traits on to the next generation (Leary, 2001). Did you know that interpersonal skills have a measurable impact on psychological and physical health? People with higher levels of interpersonal communication skills are better able to adapt to stress, have more friends, have greater satisfaction in relationships, and have less depression and anxiety (Hargie, 2011). In fact, prolonged isolation has been shown to severely damage a human (Williams & Zadro, 2001). Aside from making your relationships and health better, interpersonal communication skills are highly sought after by potential employers, consistently ranking as one of the most desired traits for new hires in national surveys (National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2019). Each of these examples illustrates how interpersonal communication meets our basic needs as humans for security in our social bonds, health, and careers. But we are not born with all the interpersonal communication skills we’ll need in life. In order to make the most out of our interpersonal relationships, we must learn some basic principles. In this chapter, we will provide an overview of some principles of interpersonal communication, discuss communication’s impact on our relationships, and provide guidance on managing interpersonal conflict.

6.1 Principles of Interpersonal Communication

In order to understand interpersonal communication, we must understand how interpersonal communication functions to meet our needs and goals and how our interpersonal communication connects to larger social and cultural systems. Interpersonal communication is the process of exchanging messages between people whose lives mutually influence one another in unique ways in relation to social and cultural norms. This definition highlights the fact that interpersonal communication involves two or more people who are interdependent to some degree and who build a unique bond based on the larger social and cultural contexts to which they belong. In this section, we will discuss both the functional and cultural aspects of interpersonal communication.

Functional Aspects of Interpersonal Communication

We have different needs that are met through our various relationships. Whether we are aware of it or not, we often ask ourselves, “What can this relationship do for me?” In order to understand how relationships achieve strategic functions, we will look at instrumental goals, relationship-maintenance goals, and self-presentation goals.

What motivates you to communicate with someone? We frequently engage in communication designed to fulfill instrumental needs, or needs that help us get things done in our day-to-day lives and achieve short- and long-term goals. Interpersonal communication intended to meet instrumental needs can include gaining compliance (getting someone to do something for us), getting information we need, or asking for support (Burleson et al., 2000). In short, instrumental talk helps us “get things done” in our relationships. The following are examples of communicating for instrumental needs:

- You ask your friend to help you move this weekend (gaining/resisting compliance).

- You ask your coworker to remind you how to balance your cash register till at the end of your shift (requesting or presenting information).

- You console your roommate after he loses his job (asking for or giving support).

Relational needs include needs that help us maintain social bonds and interpersonal relationships. When we communicate to fulfill relational needs, we are striving to maintain a positive relationship. Engaging in relationship-maintenance communication is like taking your car to be serviced at the repair shop. To have a good relationship, just as to have a long-lasting car, we should engage in routine maintenance. For example, have you ever wanted to stay in and order a pizza and watch a movie, but your friend suggests that you go to a local restaurant and then to the theatre? Maybe you don’t feel like being around a lot of people or spending money (or changing out of your pajamas), but you decide to go along with her suggestion. In that moment, you are putting your relational partner’s needs above your own, which will likely make her feel valued. It is likely that your friend has made or will also make similar concessions to put your needs first, which indicates that there is a satisfactory and complementary relationship. Other routine relational tasks include celebrating special occasions or honoring accomplishments, spending time together, and checking in regularly by phone, text, social media, or face-to-face communication. The following are examples of communicating for relational needs:

- You organize an office party for a coworker who has just become a US citizen (celebrating/honoring accomplishments).

- You make breakfast with your mom while you are home visiting (spending time together).

- You post a message on a long-distance friend’s Instagram post saying you miss him (checking in).

Identity needs include our need to present ourselves to others and be thought of in particular and desired ways. Just as many companies, celebrities, and politicians create a public image, we desire to present different faces in different contexts. The well-known scholar Erving Goffman compared self-presentation to a performance and suggested we all perform different roles in different contexts (Goffman, 1959). Indeed, competent communicators can successfully manage how others perceive them by adapting to situations and contexts. A mom may perform the role of stern head of household, supportive shoulder to cry on, or hip and culturally aware friend to her child. A newly hired employee may initially perform the role of serious and agreeable coworker. Here are some other examples of communicating to meet self-presentation goals:

- As your boss complains about struggling to format the company newsletter, you tell her about your experience with Canva and editing and offer to look over the newsletter once she’s done to fix the formatting (presenting yourself as competent).

- You and your new college roommate stand in your dorm room full of boxes. You let him choose which side of the room he wants and then invite him to eat lunch with you (presenting yourself as friendly).

- You say, “I don’t know,” in response to a professor’s question even though you have an idea of the answer (presenting yourself as aloof, or “too cool for school”).

The functional perspective of interpersonal communication indicates that we communicate to achieve certain goals in our relationships. We get things done in our relationships by communicating for instrumental goals. We maintain positive relationships through relational goals. We also strategically present ourselves in order to be perceived in particular ways. As our goals are met and our relationships build, they become little worlds we inhabit with our relational partners, complete with their own relationship cultures.

Cultural Aspects of Interpersonal Communication

Aside from functional aspects of interpersonal communication, communicating in relationships also helps establish relationship cultures. Just as large groups of people create cultures through shared symbols (language), values, and rituals, people in relationships also create cultures at a smaller level. Relationship cultures are the climates established through interpersonal communication that are unique to the relational partners but based on larger cultural and social norms. We also enter into new relationships with expectations based on experiences we have from previous relationships and knowledge we have learned from our larger society and culture. So from our life experiences in our larger cultures, we bring building blocks, or expectations, into our relationships, which fundamentally connect our relationships to the outside world (Burleson et al., 2000). Even though we experience our relationships as unique, they are at least partially built on preexisting cultural norms. Some additional communicative acts that create our relational cultures include relational storytelling, personal idioms, routines and rituals, and rules and norms.

Storytelling is an important part of how we create culture in larger contexts and how we create a uniting and meaningful storyline for our relationships. In fact, an anthropologist coined the term homo narrans to describe the unique storytelling capability of modern humans (Fisher, 1985). We often rely on relationship storytelling to create a sense of stability in the face of change, test the compatibility of potential new relational partners, or create or maintain solidarity in established relationships. Think of how you use storytelling among your friends, family, coworkers, and other relational partners. If you recently moved to a new place for college, you probably experienced some big changes. One of the first things you started to do was reestablish a social network—remember, human beings are fundamentally social creatures. As you began to encounter new people in your classes, at your new job, or in your new housing, you most likely told some stories of your life before—about your friends, job, or teachers back home. One of the functions of this type of storytelling, early in forming interpersonal bonds, is a test to see if the people you are meeting have similar stories or can relate to your previous relationship cultures. Although storytelling will continue to play a part in your relational development with these new people, you may be surprised at how quickly you start telling stories with your new friends about things that have happened since you met. You may recount stories about your first trip to the dance club together, the weird geology professor you had together, or the time you all got sick from eating the cafeteria food. In short, your old stories will start to give way to new stories that you’ve created. Storytelling within relationships helps create solidarity, or a sense of belonging and closeness.

We also create personal idioms in our relationships (Bell & Healey, 1992). If you’ve ever studied world languages, you know that idiomatic expressions like “I’m under the weather today” are basically nonsense when translated. For example, the equivalent of this expression in French translates to “I’m not in my plate today.” When you think about it, it doesn’t make sense to use either expression to communicate that you’re sick, but the meaning would not be lost on English or French speakers, because they can decode their respective idiom. This is also true of idioms we create in our interpersonal relationships. Just as idioms are unique to individual cultures and languages, personal idioms are unique to certain relationships, and they create a sense of belonging due to the inside meaning shared by the relational partners. In romantic relationships, for example, it is common for individuals to create nicknames for each other that may not directly translate for someone who overhears them. You and your partner may find that calling each other “booger” is sweet, while others may think it’s gross. Idioms help create cohesiveness, or solidarity in relationships, because they are shared cues between cultural insiders. They also communicate the uniqueness of the relationship and create boundaries, since meaning is only shared within the relationship.

Routines and rituals help form relational cultures through their natural development in repeated or habitual interaction (Burleson et al., 2000). While “routine” may connote boring in some situations, relationship routines are communicative acts that create a sense of predictability in a relationship that is comforting. Some communicative routines may develop around occasions or conversational topics. For example, it is common for long-distance friends or relatives to schedule a recurring phone conversation or for couples to review the day’s events over dinner. Other routines develop around entire conversational episodes. For example, two best friends recounting their favorite spring-break story may seamlessly switch from one speaker to the other, finish each other’s sentences, speak in unison, or gesture simultaneously because they have told the story so many times. Relationship rituals take on more symbolic meaning than do relationship routines and may be variations on widely recognized events—such as birthdays, anniversaries, and holidays—or highly individualized and original.

Relationship rules and norms help with the daily function of the relationship. They help create structure and provide boundaries for interacting in the relationship and for interacting with larger social networks (Burleson et al., 2000). Relationship rules are explicitly communicated guidelines for what should and should not be done in certain contexts. A couple could create a rule to always confer with each other before letting their child spend the night somewhere else. If a mother lets her son sleep over at a friend’s house without consulting her partner, a more serious conflict could result. Relationship norms are similar to routines and rituals in that they develop naturally in a relationship and generally conform to or are adapted from what is expected and acceptable in the larger culture or society. For example, it may be a norm that you and your coworkers do not “talk shop” at your Friday happy-hour gathering. So when someone brings up work at the gathering, his coworkers may remind him that there’s no shop talk, and the consequences may not be that serious. Regarding topics of conversation, norms often guide expectations of what subjects are appropriate within various relationships. Do you talk to your boss about your personal finances? Do you talk to your parents about your sexual activity? Do you tell your classmates about your medical history? In general, there are no rules that say you can’t discuss any of these topics with anyone you choose, but relational norms usually lead people to answer “no” to the questions above. Violating relationship norms and rules can negatively affect a relationship, but in general, rule violations can lead to more direct conflict, while norm violations can lead to awkward social interactions. Developing your interpersonal communication competence will help you assess your communication in relation to the many rules and norms you will encounter.

6.2 Communication in Relationships

Communication is at the heart of forming our interpersonal relationships. We relate to each other through the everyday conversations and otherwise trivial interactions that form the fabric of our relationships. It is through our communication that we adapt to the dynamic nature of our relational worlds, given that relational partners do not enter each encounter or relationship with compatible expectations. Communication allows us to test and be tested by our potential and current relational partners. It is also through communication that we respond when someone violates or fails to meet those expectations (Knapp & Vangelisti, 2009). In this section, we discuss how communication plays a role in how relationships come together and come apart.

Coming Together

Many communication scholars have conducted research into the formative stages of interpersonal relationships. Charles R. Berger and Richard J. Calabrese (1975) came up with Uncertainty Reduction Theory, which posits that we are uncomfortable with uncertainty and seek to reduce that uncertainty through communication. This theory explains why we engage in initial interactions with others to try and find common ground and reduce our levels of discomfort. Psychologists Irwin Altman and Dalmas Taylor (1973) introduced social penetration theory to explain how the reciprocal process of self-disclosure affects how a relationship develops. This theory compares the process of self-disclosure to an onion: in most relationships, people gradually penetrate the layers of each other’s personality, much like we peel the layers from an onion.

Communication scholar Mark Knapp (1984) identified 5 stages of “coming together” in a relationship. As you read through each stage in more detail, keep the following things in mind: relational partners do not always go through the stages sequentially, some relationships do not experience all the stages, and we do not always consciously move between stages. Although this model has been applied most often to romantic relationships, most relationships follow a similar pattern that may be adapted to a particular context.

Initiating

In the initiating stage, people size each other up and try to present themselves favorably. Whether you run into someone in the hallway at school or in the produce section at the grocery store, you scan the person and consider any previous knowledge you have of them, expectations for the situation, and so on. Initiating is influenced by several factors. If you encounter a stranger, you may say, “Hi, my name’s Rich.” If you encounter a person you already know, you’ve already gone through this before, so you may just say, “What’s up?” Time constraints also affect initiation. A quick passing calls for a quick hello, while a scheduled meeting may entail a more formal start. If you already know the person, the length of time that’s passed since your last encounter will affect your initiation. For example, if you see a friend from high school while home for winter break, you may set aside a long block of time to catch up; however, if you see someone at work that you just spoke to ten minutes earlier, you may skip initiating communication.

Experimenting

The scholars who developed these relational stages have likened the experimenting stage, where people exchange information and often move from strangers to acquaintances, to the “sniffing ritual” of animals (Knapp & Vangelisti, 2009). A basic exchange of information is typical as the experimenting stage begins. For example, on the first day of class, you may chat with the person sitting beside you and take turns sharing your year in school, hometown, residence hall, and major. Then you may branch out and see if there are any common interests that emerge. Finding out you’re both Atlanta Hawks fans could then lead to more conversation about basketball and other hobbies or interests; however, sometimes the experiment may fail. If your attempts at information exchange with another person during the experimenting stage are met with silence or hesitation, you may interpret their lack of communication as a sign that you shouldn’t pursue future interaction.

Intensifying

As we enter the intensifying stage, we indicate that we would like or are open to more intimacy, and then we wait for a signal of acceptance. This incremental intensification of intimacy can occur over a period of weeks, months, or years and may involve inviting a new friend to join you at a party, then to your place for dinner, then to go on vacation with you. It would be seen as odd, even if the experimenting stage went well, to invite a person who you’re still getting to know on vacation with you without engaging in some less intimate interaction beforehand. In order to save face and avoid making ourselves overly vulnerable, steady progression is key in this stage. Aside from sharing more intense personal time, requests for and granting favors may also play into intensification of a relationship. For example, one friend helping the other prepare for a big party on their birthday can increase closeness. However, if one person asks for too many favors or fails to reciprocate favors granted, then the relationship can become unbalanced, which could result in a transition to another stage, such as differentiating.

Integrating

In the integrating stage, two people’s identities and personalities merge, and a sense of interdependence develops. Even though this stage is most evident in romantic relationships, there are elements that appear in other relationship forms. Some verbal and nonverbal signals of the integrating stage are when the social networks of two people merge; those outside the relationship begin to refer to or treat the relational partners as if they were one person (e.g., always referring to them together—“Let’s invite Olaf and Bettina”); or the relational partners present themselves as one unit (e.g., both signing and sending one holiday card or opening a joint bank account). Even as two people integrate, they likely maintain some sense of self by spending time with friends and family separately, which helps balance their needs for independence and connection.

Bonding

The bonding stage includes a public ritual that announces formal commitment. These types of rituals include weddings, commitment ceremonies, and civil unions. Obviously, this stage is primarily applicable to romantic couples. In some ways, the bonding ritual is arbitrary, in that it can occur at any stage in a relationship. In fact, bonding rituals are often later annulled or reversed because a relationship doesn’t work out, perhaps because there wasn’t sufficient time spent in the experimenting or integrating phases. However, bonding warrants its own stage because the symbolic act of bonding can have very real effects on how two people communicate about and perceive their relationship. For example, the formality of the bond may lead the couple and those in their social network to more diligently maintain the relationship if conflict or stress threatens it.

Coming Apart

Communication scholars are also interested in the causes and impact of relationships stagnating, deteriorating, and ending. Social exchange theory essentially entails a weighing of the costs and rewards in a given relationship (Harvey & Wenzel, 2006). When we perceive the costs of a relationship as greater than the outcomes or rewards, we may negatively evaluate and potentially choose to diminish or end the relationship.

Knapp’s (1984) relationship model continues with five stages of “coming apart.” As you read through these stages, remember that there is nothing innately positive or negative about relationships coming together or coming apart. These stages are also not a prediction or a prescription—many relationships that enter these stages can be repaired, others may stall at a certain point and never progress to the termination stage, while others may skip several stages and end abruptly. Still, these stages provide insight into the complicated process that affects relational deterioration.

Differentiating

Individual differences can present a challenge at any given stage in the relational interaction model; however, in the differentiating stage, communicating these differences becomes a primary focus. Differentiating is the reverse of integrating, as we and our reverts back to I and my. For example, Carrie may reclaim friends who became “shared” as she got closer to her roommate Julie and their social networks merged by saying, “I’m having my friends over to the apartment and would like to have privacy for the evening.” Differentiating may occur in a relationship that bonded before the individuals knew each other in enough depth and breadth. Even in relationships where the bonding stage is less likely to be experienced, such as a friendship, unpleasant discoveries about the other person’s past, personality, or values during the integrating or experimenting stage could lead a person to begin differentiating.

Circumscribing

To circumscribe means to draw a line around something or put a boundary around it (Oxford English Dictionary Online, 2011). In the circumscribing stage of a relationship, communication decreases and certain areas or subjects become restricted as individuals verbally close themselves off from each other. They may say things like “I don’t want to talk about that anymore” or “You mind your business and I’ll mind mine.” If one person was more interested in differentiating in the previous stage, or the desire to end the relationship is one-sided, verbal expressions of commitment may go unechoed—for example, when one person’s statement, “I know we’ve had some problems lately, but I still like being with you,” is met with silence. Passive-aggressive behavior may occur more frequently in this stage. Once the increase in boundaries and decrease in communication becomes a pattern, the relationship further deteriorates toward stagnation.

Stagnating

During the stagnating stage, the relationship may come to a standstill, as individuals basically wait for the relationship to end. Outward communication may be avoided, but internal communication may be frequent. During this stage, a person’s internal thoughts may lead them to avoid communication. For example, a person may think, “There’s no need to bring this up again, because I know exactly how he’ll react!” This stage can be prolonged in some relationships. Parents and children who are estranged, couples who are separated and awaiting a divorce, or friends who want to end a relationship but don’t know how to do it may have extended periods of stagnation. Short periods of stagnation may occur right after a failed exchange in the experimental stage, where you may be in a situation that’s not easy to get out of, but the person is still there. Although most people don’t like to linger in this unpleasant stage, some may do so to avoid potential pain from termination, some may still hope to rekindle the spark that started the relationship, or some may enjoy leading their relational partner on.

Avoiding

Moving to the avoiding stage may be a way to end the awkwardness that comes with stagnation, as people signal that they want to close down the lines of communication. Communication in the avoiding stage can be very direct—“I don’t want to talk to you anymore”—or more indirect—“I have to meet someone in a little while, so I can’t talk long.” While physical avoidance such as leaving a room or requesting a schedule change at work may help clearly communicate the desire to terminate the relationship, we don’t always have that option. In a parent-child relationship, where the child is still dependent on the parent, or in a roommate situation, where a lease agreement prevents leaving, people may engage in cognitive dissociation, which means they mentally shut down and ignore the other person even though they are still physically copresent.

Terminating

The terminating stage of a relationship can occur shortly after initiation or after a ten- or twenty-year relational history has been established. Termination can result from outside circumstances such as geographic separation or internal factors such as changing values or personalities that lead to a weakening of the bond. Termination exchanges involve some typical communicative elements and may begin with a summary message that recaps the relationship and provides a reason for the termination (e.g., “We’ve had some ups and downs over our three years together, but I’m getting ready to go to college, and I either want to be with someone who is willing to support me, or I want to be free to explore who I am.”). The summary message may be followed by a distance message that further communicates the relational drift that has occurred (e.g., “We’ve really grown apart over the past year.”), which may be followed by a disassociation message that prepares people to be apart by projecting what happens after the relationship ends (e.g., “I know you’ll do fine without me. You can use this time to explore your options and figure out if you want to go to college too or not.”). Finally, there is often a message regarding the possibility for future communication in the relationship (e.g., “I think it would be best if we don’t see each other for the first few months, but text me if you want to.”) (Knapp & Vangelisti, 2009).

6.3 Conflict and Interpersonal Communication

Who do you have the most conflict with right now? Your answer to this question probably depends on the various contexts in your life. If you still live at home with a parent or parents, you may have daily conflicts with your family as you try to balance your autonomy, or desire for independence, with the practicalities of living under your family’s roof. If you’ve recently moved away to go to college, you may be negotiating roommate conflicts as you adjust to living with someone you may not know at all. You probably also have experiences managing conflict in romantic relationships or in the workplace. So think back and ask yourself, “How well do I handle conflict?” As with all areas of communication, we can improve if we have the background knowledge to identify relevant communication phenomena and the motivation to reflect on and enhance our communication skills.

Interpersonal conflict occurs in interactions where there are real or perceived incompatible goals, scarce resources, or opposing viewpoints. Interpersonal conflict may be expressed verbally or nonverbally along a continuum ranging from a nearly imperceptible cold shoulder to a very obvious blowout. Conflict is an inevitable part of close relationships and can take a negative emotional toll. It takes effort to ignore someone or be passive-aggressive, and the anger or guilt we may feel after blowing up at someone are valid negative feelings. However, conflict isn’t always negative or unproductive. In fact, numerous research studies have shown that the quantity of conflict in a relationship is not as important as how the conflict is handled (Markman et al., 1993). Additionally, when conflict is well managed, it has the potential to lead to more rewarding and satisfactory relationships (Canary & Messman, 2000). This section explores interpersonal conflict by identifying common conflict patterns and reviewing strategic choices for managing conflict.

Identifying Conflict Patterns

Conflict is inevitable and it is not inherently negative. A key part of developing interpersonal communication competence involves being able to effectively manage the conflict you will encounter in all your relationships. To handle conflict better, it is beneficial to notice patterns of conflict in specific relationships and to develop an idea of what causes you to react negatively and what your reactions usually are.

Triggers of Conflict

Four common triggers for conflict are criticism, demand, cumulative annoyance, and rejection (Christensen & Jacobson, 2000). We all know from experience that criticism, or comments that evaluate another person’s personality, behavior, appearance, or life choices, may lead to conflict. Comments do not have to be meant as criticism to be perceived as such. If Gary comes home from college for the weekend and his mom says, “Looks like you put on a few pounds,” she may view this as a statement of fact based on observation. Gary, however, may take the comment personally and respond negatively back to his mom, starting a conflict that will last for the rest of his visit. A simple but useful strategy to manage the trigger of criticism is to follow the old adage “Think before you speak.” In many cases, there are alternative ways to phrase things that may be taken less personally, or we may determine that our comment doesn’t need to be spoken at all.

Demands also frequently trigger conflict, especially if the demand is viewed as unfair or irrelevant. As with criticism, thinking before you speak and before you respond can help manage demands and minimize conflict episodes. Oftentimes, demands are met with withdrawal rather than a verbal response. If you are doing the demanding, remember a higher level of information exchange may make your demand clearer or more reasonable to the other person. If you are being demanded of, responding calmly and expressing your thoughts and feelings are likely more effective than withdrawing, which may escalate the conflict.

Cumulative annoyance is a building of frustration or anger that occurs over time, eventually resulting in a conflict interaction. For example, your friend shows up late to drive you to class three times in a row. You didn’t say anything the previous times, but on the third time you say, “You’re late again! If you can’t get here on time, I’ll find another way to get to class.” Cumulative annoyance can build up like a pressure cooker, and as it builds up, the intensity of the conflict also builds. The problem here is that while the annoyance builds up for one individual, the other may be completely unaware of the problem. You’ve likely been surprised when someone has blown up at you due to cumulative annoyance or surprised when someone you have blown up at didn’t know there was a problem building. A good strategy for managing cumulative annoyance is to monitor your level of annoyance and occasionally let some steam out of the pressure cooker by processing through your frustration with a third party or directly addressing what is bothering you with the source.

No one likes the feeling of rejection. Rejection can lead to conflict when one person’s comments or behaviors are perceived as ignoring or invalidating the other person. Vulnerability is a component of any close relationship. When we care about someone, we verbally or nonverbally communicate. We may tell our best friend that we miss them, or plan a home-cooked meal for our partner who is working late. The vulnerability that underlies these actions comes from the possibility that our relational partner will not notice or appreciate them. When someone feels exposed or rejected, they often respond with anger to mask their hurt, which ignites a conflict. Managing feelings of rejection is difficult because it is so personal, but controlling the impulse to assume that your relational partner is rejecting you, and engaging in communication rather than reflexive reaction, can help put things in perspective. If your partner doesn’t get excited about the meal you planned and cooked, it could be because they are physically or mentally tired after a long day.

Reactions to Conflict

Two common conflict pitfalls are one-upping and mindreading (Gottman, 1994). One-upping is a quick reaction to communication from another person that escalates the conflict. If Sam comes home late from work and Nicki says, “I wish you would call when you’re going to be late” and Sam responds, “I wish you would get off my back,” the reaction has escalated the conflict. Mindreading is communication in which one person attributes something to the other using generalizations. If Sam says, “You don’t care whether I come home at all or not,” she is presuming to know Nicki’s thoughts and feelings. Nicki is likely to respond defensively, perhaps saying, “You don’t know how I’m feeling!” One-upping and mindreading are often reactions that are more reflexive than deliberate. Taking a moment to respond mindfully rather than react with a knee-jerk reflex can lead to information exchange, which could deescalate the conflict.

Validating the person with whom you are in conflict can be an effective way to deescalate conflict. Often validation can be as simple as demonstrating good listening skills like making eye-contact and giving verbal and nonverbal back-channel cues like saying “mmm-hmm” or nodding your head (Gottman, 1994). This doesn’t mean that you must give up your own side in a conflict or that you agree with what the other person is saying. Rather, you are hearing the other person out, which validates them and may also give you some more information about the conflict that could minimize the likelihood of a reaction rather than a response.

As with all the aspects of communication competence we have discussed so far, you cannot expect that everyone you interact with will have the same knowledge of communication that you have. But it often only takes one person with conflict management skills to make an interaction more effective. Remember that it’s not the quantity of conflict that determines a relationship’s success; it’s how the conflict is managed, and one person’s competent response can deescalate a conflict.

Conflict Management Styles

Would you describe yourself as someone who prefers to avoid conflict? Do you like to get your way? Are you good at working with someone to reach a solution that is mutually beneficial? Odds are that you have been in situations where you could answer yes to each of these questions, which underscores the important role context plays in conflict and conflict management styles. The way we view and deal with conflict is learned and contextual.

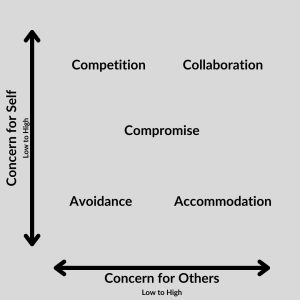

There has been much research done on different types of conflict management styles, which are communication strategies that attempt to avoid, address, or resolve a conflict. The five strategies for managing conflict we will discuss are competition, avoidance, accommodation, compromise, and collaboration. Each of these conflict styles accounts for the concern we place on self versus the concern we place on others (see Figure 6.1 “Five Styles of Interpersonal Conflict Management”).

Competition

The competing style indicates a high concern for self and a low concern for other. When we compete, we are striving to “win” the conflict, potentially at the expense or “loss” of the other person. One way we may gauge our win is by being granted or taking concessions from the other person. Competition can be negative in relationships if it is linked to aggression or creates hostility. In many scenarios, a “win” for one person could only be a short-term result and could lead to conflict escalation. Interpersonal conflict is rarely isolated, meaning there can be ripple effects that connect the current conflict to previous and future conflicts. Competition in relationships isn’t always negative, and people who enjoy engaging in competition may not always do so at the expense of another person’s goals. In fact, research has shown that some couples engage in competitive shared activities like sports or games to maintain and enrich their relationship (Dindia & Baxter, 1987).

Avoidance

The avoiding style of conflict management often indicates a low concern for self and a low concern for other, and no direct communication about the conflict takes place. The avoiding style is either passive or indirect, meaning there is little information exchange, which may make this strategy less effective than others. We may decide to avoid conflict for many different reasons, some of which are better than others. If you view the conflict as having little importance to you, it may be better to ignore it. If the person you’re having conflict with will only be working in your office for a week, you may perceive a conflict to be temporary and choose to avoid it and hope that it will solve itself. In both of these cases, avoiding doesn’t really require an investment of time, emotion, or communication skill, so there is not much at stake to lose. Unfortunately, avoidance is not always an easy conflict management choice, as the person we have conflict with isn’t usually a temp in our office or a weekend houseguest. When conflict arises in a meaningful, long-term relationship, avoidance can just make a problem worse. For example, avoidance could first manifest as changing the subject, then progress from avoiding the issue to avoiding the person altogether, to even ending the relationship.

Accommodation

The accommodating conflict management style indicates a low concern for self and a high concern for other and is often viewed as passive or submissive, in that someone complies with or obliges another without providing personal input. The context for and motivation behind accommodating play an important role in whether or not it is an appropriate strategy. Generally, we accommodate because we are being generous, we are obeying, or we are yielding (Bobot, 2010). If we are being generous, we accommodate because we genuinely want to; if we are obeying, we don’t have a choice but to accommodate (perhaps due to the potential for negative consequences or punishment); and if we yield, we may have our own views or goals but give up on them due to fatigue, time constraints, or because a better solution has been offered. Accommodating can be appropriate when there is little chance that our own goals can be achieved, when we don’t have much to lose by accommodating, when we feel we are wrong, or when advocating for our own needs could negatively affect the relationship (Isenhart & Spangle, 2000). The occasional accommodation can be useful in maintaining a relationship, but one-sided accommodation over time is a sign of an unhealthy power dynamic between friends or romantic partners.

Compromise

The compromising style shows a moderate concern for self and other and may indicate that there is a low investment in the conflict and/or the relationship. Even though we often hear that the best way to handle a conflict is to compromise, the compromising style isn’t a win/win solution; it is a partial win/lose. In essence, when we compromise, we give up some or most of what we want. It’s true that the conflict gets resolved temporarily, but lingering thoughts of what you gave up could lead to a future conflict. Compromising may be a good strategy when there are time limitations or when prolonging a conflict may lead to relationship deterioration. Compromise may also be good when both parties have equal power or when other resolution strategies have not worked (Macintosh & Stevens, 2008).

Collaboration

The collaborating style involves a high degree of concern for self and other and usually indicates investment in the conflict situation and the relationship. Although the collaborating style takes the most work in terms of communication competence, it ultimately leads to a win/win situation in which neither party has to make concessions because a mutually beneficial solution is discovered or created. The obvious advantage is that both parties are satisfied, which could lead to positive problem solving in the future and strengthen the overall relationship. The disadvantage is that this style is often time consuming, and only one person may be willing to use this approach while the other person is eager to compete to meet their goals or willing to accommodate.

Here are some tips for collaborating and achieving a win/win outcome (Hargie, 2011):

- Do not view the conflict as a contest you are trying to win.

- Remain flexible and realize there are solutions yet to be discovered.

- Distinguish the people from the problem (don’t make it personal).

- Determine what the underlying needs are that are driving the other person’s demands (needs can still be met through different demands).

- Identify areas of common ground or shared interests that you can work from to develop solutions.

- Ask questions to allow them to clarify and to help you understand their perspective.

- Listen carefully and provide verbal and nonverbal feedback.

Key Concepts: Conflict Management

Whether you have a roommate by choice, by necessity, or through the random selection process of your school’s housing office, it’s important to be able to get along with the person who shares your living space. While having a roommate offers many benefits such as making a new friend, having someone to experience a new situation like college life with, and having someone to split the cost on your own with, there are also challenges. Some common roommate conflicts involve neatness, noise, having guests, sharing possessions, value conflicts, money conflicts, and personality conflicts (Ball State University, 2001). Read the following scenarios and answer the discussion questions that follow:

Scenario 1: Noise and having guests. Your roommate has a job waiting tables and gets home around midnight on Thursday nights. She often brings a couple of friends from work home with her. They watch television, listen to music, or play video games and talk and laugh. You have an 8 a.m. class on Friday mornings and are usually asleep when she returns. Last Friday, you talked to her and asked her to keep it down in the future. Tonight, their noise has woken you up and you can’t get back to sleep.

Scenario 2: Sharing possessions. When you go out to eat, you often bring back leftovers to have for lunch the next day during your short break between classes. You didn’t have time to eat breakfast, and you’re really excited about having your leftover pizza for lunch until you get home and see your roommate sitting on the couch eating the last slice.

Scenario 3: Value and personality conflicts. You like to go out to clubs and parties and have friends over, but your roommate is much more of an introvert. You’ve tried to get her to come out with you or join the party at your place, but she’d rather study. One day she tells you that she wants to break the lease so she can move out early to live with one of her friends. You both signed the lease, so you have to agree or she can’t do it. If you break the lease, you automatically lose your portion of the security deposit.

Discussion Questions:

- Which conflict management style, from the five discussed, would you use in this situation?

- What are the potential strengths of using this style?

- What are the potential weaknesses of using this style?

References

Altman, I., & Taylor, D. (1973). Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships. Holt.

Ball State University (n.d.). Roommate conflicts. Retrieved June 16, 2011, from http://cms.bsu.edu/CampusLife/CounselingCenter/VirtualSelfHelpLibrary/RoommateIssues.aspx

Bell, R. A., & Healey, J. G. (1992). Idiomatic communication and interpersonal solidarity in friends’ relational cultures. Human Communication Research, 18(3), 307–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1992.tb00555.x

Berger, C. R., & Calabrese, R. J. (1975). Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond: Toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Human Communication Research, 1(2), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1975.tb00258.x

Bobot, L. (2010). Conflict management in buyer-seller relationships. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 27(3), 291–319. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1002/crq.260

Burleson, B. R., Metts, S., & Kirch, M. W. (2000). Communication in close relationships. In C. Hendrick & S. S. Hendrick (Eds.), Close relationships: A sourcebook (pp. 45–258). Sage.

Canary, D. J., & Messman, S. J. (2000). Relationship conflict. In C. Hendrick & S. S. Hendrick (Eds.), Close relationships: A sourcebook (pp. 261–270). Sage.

Christensen, A., & Jacobson, N. S. (2000). Reconcilable differences. Guilford Press.

Dindia, K., & Baxter, L. A. (1987). Strategies for maintaining and repairing marital relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 4(2), 143–158. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1177/0265407587042003

Fisher, W. R. (1985). Narration as human communication paradigm: The case of public moral argument. Communication Monographs, 51(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758409390180

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor Books.

Gottman, J. M. (1994). What predicts divorce? The relationship between marital processes and marital outcomes. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hargie, O. (2011). Skilled interpersonal interaction: Research, theory, and practice. Routledge.

Harvey, J. H., & Wenzel, A. (2006). Theoretical perspectives in the study of close relationships. In A. L. Vangelisti & D. Perlman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (pp. 35–49). Cambridge University Press.

Isenhart, M. W., & Spangle, M. (2000). Collaborative approaches to resolving conflict. Sage.

Knapp, M. L. (1984). Interpersonal communication and human relationships. Allyn and Bacon.

Knapp, M. L., & Vangelisti, A. L. (2009). Interpersonal communication and human relationships. Pearson.

Leary, M. R. (2001). Toward a conceptualization of interpersonal rejection. In M. R. Leary (Ed.), Interpersonal rejection (pp. 3–20). Oxford University Press.

Macintosh, G., & Stevens, C. (2008). Personality, motives, and conflict strategies in everyday service encounters. International Journal of Conflict Management, 19(2), 112–131. https://doi.org/10.1108/10444060810856067

Markman, H. J., Renick, M. J., Floyd, F. J., Stanley, S. M., & Clements, M. (1993). Preventing marital distress through communication and conflict management training: A 4- and 5-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(1), 70–77. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-006X.61.1.70

National Association of Colleges and Employers. (2019). Job outlook 2019. https://www.naceweb.org/

Oxford University Press. (n.d.). Circumscribe. In Oxford English dictionary online. Retrieved September 13, 2011, from http://www.oed.com

Williams, K. D., & Zadro, L. (2001). Ostracism: On being ignored, excluded, and rejected. In M. R. Leary (Ed.), Interpersonal rejection (pp. 21–54). Oxford University Press.

Credits

Chapter 6 was adapted, remixed, and curated from Chapters 6 and 7 of Communication in the Real World: An Introduction to Communication Studies, a work produced and distributed under a CC BY-NC-SA license in 2013 by a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution.