Chapter 3: Verbal Communication

Learning Objectives

- Identify and discuss the functions of language.

- Distinguish between denotation and connotation.

- Identify and discuss the four main types of linguistic expressions.

- Discuss the power of language to express our identities, affect our credibility, control others, and perform actions.

- Explain how grammar and slang contribute to the dynamic nature of language.

- Identify the ways in which language can separate people and bring them together.

- Identify strategies for using language to accomplish goals.

When we first think about communication, we most likely come up with examples of verbal communication. Talking in person with friends, chatting over FaceTime with family, listening to a podcast, and giving a presentation are all examples of verbal communication. This chapter defines verbal communication as the process of generating meaning using language. Notably, this can include spoken or written words. To demonstrate verbal communication’s role and consequence in our lives, this chapter will discuss the relationship between language and meaning and will provide guidance on how to use words well.

3.1 Language and Meaning

The relationship between language and meaning is not a straightforward one. One reason for this complicated relationship is the limitlessness of modern language systems like English (Crystal, 2005). Language is productive in the sense that there are an infinite number of utterances we can make by connecting existing words in new ways. In addition, there is no limit to a language’s vocabulary, as new words are coined daily. Of course, the complicated relationship between language and meaning can sometimes lead to confusion, frustration, or even humor. We may even experience a little of all three, when we stop to think about how there are some twenty-five definitions available to tell us the meaning of the word meaning! (Crystal, 2005). Since language and symbols are the primary vehicle for our communication, it is important that we not take the characteristics of our verbal communication for granted. In this section, we will discuss how language is symbolic, expressive, powerful, dynamic, and relational.

Language is Symbolic

You’ll recall from Chapter 1 that our language system is primarily made up of symbols, signifiers that stand in for or represent something else. Symbols can be communicated verbally (speaking the word hello), in writing (putting the letters H-E-L-L-O together), or nonverbally (waving your hand back and forth). In any case, the symbols we use stand in for something else, like a physical object or an idea. They do not actually correspond to the thing being referenced in any direct way. Unlike hieroglyphics in ancient Egypt, which often did have a literal relationship between the written symbol and the object being referenced, the symbols used in modern languages look nothing like the object or idea to which they refer.

Definitions help us narrow the meaning of particular symbols, but it is important to recognize that symbols have both denotative and connotative meanings. Denotation refers to definitions that are accepted by the language group as a whole, or the dictionary definition of a word. For example, the denotation of the word cowboy is a man who takes care of cattle. Another denotation is a reckless and/or independent person. A more abstract word, like change, would be more difficult to understand due to the word’s multiple denotations.

Connotation refers to definitions that are based on emotion- or experience-based associations people have with a word. Returning to our previous examples, the word change can have positive or negative connotations depending on a person’s experiences. A person who just ended a long-term relationship may think of change as good or bad depending on what they thought about their former partner. A word like cowboy has many connotations. For example, many connect the word to the frontier and the western history of the United States, which has mythologies associated with it that help shape the narrative of the nation. While people who grew up with cattle or have family that ranch may have a very specific connotation of the word cowboy based on personal experience, other people’s connotations may be more influenced by popular cultural symbolism like that seen in westerns.

Language is Expressive

At its essence, language is expressive. Verbal expressions help us communicate our observations, thoughts, feelings, and needs (McKay et al., 1995).

Expressing Observations

When we express observations, we report on the sensory information we are taking or have taken in. Eyewitness testimony is a good example of communicating observations. Witnesses are not supposed to make judgments or offer conclusions; they only communicate factual knowledge as they experienced it. For example, a witness could say, “I saw a white Mitsubishi Eclipse leaving my neighbor’s house at 10:30 pm.” When you are trying to make sense of an experience, expressing observations in a descriptive rather than evaluative way can lessen defensiveness, which facilitates competent communication.

Expressing Thoughts

When we express thoughts, we draw conclusions based on what we have experienced. Whereas our observations are based on sensory information (what we saw, what we read, what we heard), thoughts are connected to our beliefs (what we think is true/false), attitudes (what we like and dislike), and values (what we think is right/wrong or good/bad). Jury members are expected to express thoughts based on reported observations to help reach a conclusion about someone’s guilt or innocence. A juror might express the following thought: “The neighbor who saw the car leaving the night of the crime seemed credible. And the defendant seemed to have a shady past—I think he’s trying to hide something.”

Expressing Feelings

When we express feelings, we communicate our emotions. Expressing feelings is a difficult part of verbal communication because there are many social norms about how, why, when, where, and to whom we express our emotions. Norms for emotional expression also vary based on cultural identities and characteristics such as age and gender. In terms of age, young children are typically freer to express positive and negative emotions in public. Gendered elements intersect with age as boys grow older and are socialized into a norm of emotional restraint. Although individual men vary in the degree to which they are emotionally expressive, there is still a prevailing social norm that encourages and even expects women to be more emotionally expressive than men.

Even though expressing feelings is more complicated than other forms of expression, emotion sharing is an important part of how we create social bonds and empathize with others, and it can be improved. In order to verbally express our emotions, it is important that we develop an emotional vocabulary. The more specific we can be when we are verbally communicating our emotions, the less ambiguous our emotions will be for the person decoding our message. As we expand our emotional vocabulary, we are able to convey the intensity of the emotion we’re feeling whether it is mild, moderate, or intense. For example, happy is mild, delighted is moderate, and ecstatic is intense; ignored is mild, rejected is moderate, and abandoned is intense (Hargie, 2011).

Expressing Needs

When we express needs, we are communicating in an instrumental way to help us get things done. Since we almost always know our needs more than others do, it’s important for us to be able to convey those needs to others. Expressing needs can help us get a project done at work or help us navigate the changes of a long-term romantic partnership. Not expressing needs can lead to feelings of abandonment, frustration, or resentment. For example, if one romantic partner expresses the following thought, “I think we’re moving too quickly in our relationship,” but doesn’t also express a need, the other person in the relationship doesn’t have a guide for what to do in response to the expressed thought. Stating, “I need to spend some time with my hometown friends this weekend. Would you mind if I went home by myself?” would likely make the expression more effective. Be cautious of letting evaluations or judgments sneak into your expressions of need. Saying, “I need you to stop suffocating me!” really expresses a thought-feeling mixture more than a need.

Language is Powerful

The contemporary American philosopher David Abram wrote, “Only if words are felt, bodily presences, like echoes or waterfalls, can we understand the power of spoken language to influence, alter, and transform the perceptual world” (Abram, 1997). This statement encapsulates many of the powerful features of language. Next, we will discuss how language expresses our identities, affects our credibility, serves as a means of control, and performs actions.

Language Expresses Our Identities

The power of language to express our identities varies depending on the origin of the label (self-chosen or other-imposed) and the context. People are usually comfortable with the language they use to describe their own identities but may have issues with the labels others place on them. In terms of context, many people express their “Irish” identity on St. Patrick’s Day, but they may not think much about it over the rest of the year. There are many examples of people who have taken a label that was imposed on them, one that usually has negative connotations, and intentionally used it in ways that counter previous meanings. Some country music singers and comedians have reclaimed the label redneck, using it as an identity marker they are proud of rather than a pejorative term. Other examples of people reclaiming identity labels include the “black is beautiful” movement of the 1960s that repositioned black as a positive identity marker for African Americans and the “queer” movement of the 1980s and ’90s that reclaimed queer as a positive identity marker for some gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people. Even though some people embrace reclaimed words, they can still carry their negative connotations and are not openly accepted by everyone.

Language Affects Our Credibility

One of the goals of this chapter is to help you be more competent with your verbal communication. People make assumptions about your credibility based on how you speak and what you say. You have to use language clearly and be accountable for what you say in order to be seen as trustworthy. Using informal language and breaking social norms wouldn’t enhance your credibility during a professional job interview, but it might with your friends at a party. Politicians know that the way they speak affects their credibility, but they also know that using words that are too scientific or academic can lead people to perceive them as eggheads, which would hurt their credibility. Politicians and many others in leadership positions need to be able to use language to put people at ease, relate to others, and still appear confident and competent.

Language is a Means of Control

Control is a word that has negative connotations, but our use of it here can be positive, neutral, or negative. Verbal communication can be used to reward and punish. We can offer verbal communication in the form of positive reinforcement to praise someone. We can withhold verbal communication or use it in a critical, aggressive, or hurtful way as a form of negative reinforcement.

Directives are utterances that try to get another person to do something. They can range from a rather polite ask or request to a more forceful command or insist. Context informs when and how we express directives and how people respond to them. Promises are often paired with directives in order to persuade people to comply, and those promises, whether implied or stated, should be kept in order to be an ethical communicator. Keep this in mind to avoid arousing false expectations on the part of the other person (Hayakawa & Hayakawa, 1990).

Rather than verbal communication being directed at one person as a means of control, the way we talk creates overall climates of communication that may control many. Verbal communication characterized by empathy, understanding, respect, and honesty creates open climates that lead to more collaboration and more information exchange. Verbal communication that is controlling, deceitful, and vague creates a closed climate in which people are less willing to communicate and less trusting (Brown & Edmunds, 2019).

Language is Dynamic

As we have discussed, language is essentially limitless. We may create a one-of-a-kind sentence combining words in new ways and never know it. Aside from the endless structural possibilities, words change meaning, and new words are created daily. In this section, we’ll learn more about the dynamic nature of language by focusing on grammar and slang.

Grammar

Any language system has to have rules to make it learnable and usable. Grammar refers to the rules that govern how words are used to make phrases and sentences. Someone would likely know what you mean by the question “Where’s the remote control?” But “The control remote where’s?” is likely to be unintelligible or at least confusing (Crystal, 2005). Knowing the rules of grammar is important in order to be able to write and speak to be understood, but knowing these rules isn’t enough to make you an effective communicator. Even though teachers have long enforced the idea that there are right and wrong ways to write and say words, there really isn’t anything inherently right or wrong about the individual choices we make in our language use. Rather, it is our collective agreement that gives power to the rules that govern language.

Some linguists have viewed the rules of language as fairly rigid and limiting in terms of the possible meanings that we can create with words and sentences within that system (de Saussure, 1974). Others have viewed these rules as more open and flexible, allowing a person to make choices to determine meaning (Eco, 1976).

Looking back to our discussion of connotation, we can see how individuals play a role in how meaning and language are related, since we each bring our own emotional and experiential associations with a word that are often more meaningful than a dictionary definition. In addition, we have quite a bit of room for creativity, play, and resistance with the symbols we use. Have you ever had a secret code with a friend that only you knew? This can allow you to use a code word in a public place to get meaning across to the other person who is “in the know” without anyone else understanding the message. The fact that you can take a word, give it another meaning, have someone else agree on that meaning, and then use the word in your own fashion clearly demonstrates the dynamic nature of language. As we will discuss next, many slang words developed because people wanted a covert way to talk about certain topics without outsiders catching on.

Slang

Slang is a great example of the dynamic nature of language. Slang refers to new or adapted words that are specific to a group, context, and/or time period; regarded as less formal; and representative of people’s creative play with language. Research has shown that only about 10 percent of the slang terms that emerge over a fifteen-year period survive. Many more take their place though, as new slang words are created using inversion, reduction, or old-fashioned creativity (Allan & Burridge, 2006). Inversion is a form of word play that produces slang words like sick, wicked, and bad that refer to the opposite of their typical meaning. Reduction creates slang words such as pic, sec, and later from picture, second, and see you later. New slang words often represent what is edgy, current, or simply relevant to the daily lives of a group of people. Many creative examples of slang refer to illegal or socially taboo topics like sex, drinking, and drugs. It makes sense that developing an alternative way to talk about taboo topics could make life easier for the people who want to discuss them. Slang allows people who are in “in the know” to break the code and presents a linguistic barrier for unwanted outsiders.

It’s often difficult for us to identify the slang we use at any given moment because it is worked into our everyday language patterns and becomes very natural. Just as we learned here, new words can create a lot of buzz and become a part of common usage very quickly. The same can happen with new slang terms. Most slang words also disappear quickly, and their alternative meaning fades into obscurity. For example, you don’t hear anyone using the word macaroni to refer to something cool or fashionable. But that’s exactly what the common slang meaning of the word was at the time the song “Yankee Doodle” was written. Yankee Doodle isn’t saying the feather he sticks in his cap is a small, curved pasta shell; he is saying it’s cool or stylish.

Language is Relational

We use verbal communication to initiate, maintain, and terminate our interpersonal relationships. The first few exchanges with a potential romantic partner or friend help us size the other person up and figure out if we want to pursue a relationship or not. We then use verbal communication to remind others how we feel about them and to check in with them—engaging in relationship maintenance through language use. When negative feelings arrive and persist, or for many other reasons, we often use verbal communication to end a relationship.

Language Can Bring Us Together

Interpersonally, verbal communication is key to bringing people together and maintaining relationships. Whether intentionally or unintentionally, our use of words like I, you, we, our, and us affect our relationships. “We language” includes the words we, our, and us and can be used to promote a feeling of inclusiveness. “I language” can be useful when expressing thoughts, needs, and feelings because it leads us to “own” our expressions and avoid the tendency to mistakenly attribute the cause of our thoughts, needs, and feelings to others. Communicating emotions using “I language” may also facilitate emotion sharing by not making our conversational partner feel at fault or defensive. For example, instead of saying, “You’re making me crazy!” you could say, “I’m starting to feel really anxious because we can’t make a decision about this.” Conversely, “you language” can lead people to become defensive and feel attacked, which could be divisive and result in feelings of interpersonal separation.

Aside from the specific words that we use, the frequency of communication impacts relationships. Of course, the content of what is said is important, but research shows that romantic partners who communicate frequently with each other and with mutual friends and family members experience less stress and uncertainty in their relationship and are more likely to stay together (McCornack, 2007). When frequent communication combines with supportive messages, which are messages communicated in an open, honest, and non-confrontational way, people are sure to come together.

Language Can Separate Us

Whether it’s criticism, teasing, or language differences, verbal communication can also lead to feelings of separation. Language differences alone do not present insurmountable barriers. We can learn other languages with time and effort, there are other people who can translate and serve as bridges across languages, and we can also communicate quite a lot nonverbally in the absence of linguistic compatibility. People who speak the same language can intentionally use language to separate. The words us and them can be a powerful start to separation. Think of how language played a role in segregation in the United States as the notion of “separate but equal” was upheld by the Supreme Court and how apartheid affected South Africa as limits, based on finances and education, were placed on the Black majority’s rights to vote.

At the interpersonal level, unsupportive messages can make others respond defensively, which can lead to feelings of separation and actual separation or dissolution of a relationship. It’s impossible to be supportive in our communication all the time, but consistently unsupportive messages can hurt others’ self-esteem, escalate conflict, and lead to defensiveness. People who regularly use unsupportive messages may create a toxic win/lose climate in a relationship. Six common verbal tactics that can lead to feelings of defensiveness and separation include:

- Global labels. “You’re a liar.” Labeling someone irresponsible, untrustworthy, selfish, or lazy calls their whole identity as a person into question. Such sweeping judgments and generalizations are sure to only escalate a negative situation.

- Sarcasm. “No, you didn’t miss anything in class on Wednesday. We just sat here and looked at each other.” Even though sarcasm is often disguised as humor, it usually represents passive-aggressive behavior through which a person indirectly communicates negative feelings.

- Dragging up the past. “I should have known not to trust you when you never paid me back that $100 I let you borrow.” Bringing up negative past experiences is a tactic used by people when they don’t want to discuss a current situation. Sometimes people have built up negative feelings that are suddenly let out by a seemingly small thing in the moment.

- Negative comparisons. “Jade graduated from college without any credit card debt. I guess you’re just not as responsible as her.” Holding a person up to the supposed standards or characteristics of another person can lead to feelings of inferiority and resentment. Parents and teachers may unfairly compare children to their siblings.

- Judgmental “you” statements. “You’re never going to be able to hold down a job.” Accusatory messages are usually generalized overstatements about another person that go beyond labeling but still do not describe specific behavior in a productive way.

- Threats. “If you don’t stop texting back and forth with your ex, both of you are going to regret it.” Threatening someone with violence or some other negative consequence usually signals the end of productive communication. Aside from the potential legal consequences, threats usually overcompensate for a person’s insecurity.

3.2 Using Words Well

Have you ever gotten lost because someone gave you directions that didn’t make sense to you? Have you ever puzzled over the instructions for how to put something like a bookshelf or grill together? When people don’t use words well, there are consequences that range from mild annoyance to legal actions. When people do use words well, they can be inspiring and make us better people. In this section, we will learn how to use words well by using words clearly, using words affectively, and using words ethically.

Using Words Clearly

The level of clarity with which we speak varies depending on whom we talk to, the situation we’re in, and our own intentions and motives. We sometimes make a deliberate effort to speak as clearly as possible. We can indicate this concern for clarity nonverbally by slowing our rate or verbally by saying, “Frankly…” or “Let me be clear…” Sometimes it can be difficult to speak clearly—for example, when we are speaking about something with which we are unfamiliar. Emotions and distractions can also interfere with our clarity. Being aware of the varying levels of abstraction within language can help us create clearer messages.

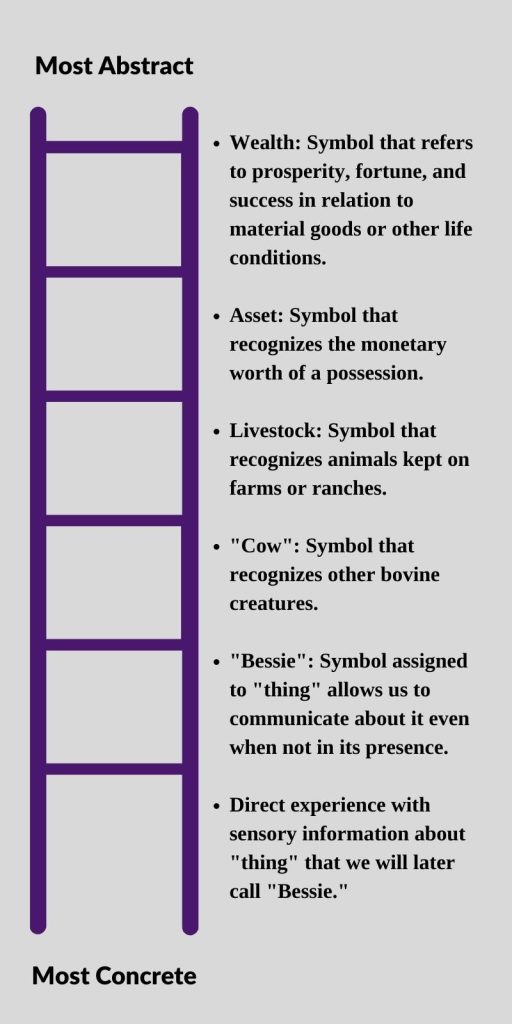

The ladder of abstraction, illustrated in Figure 3.1, is a model used to demonstrate how language can range from concrete to abstract. As we follow a concept up the ladder of abstraction, more and more of the “essence” of the original object is lost or left out, which leaves more room for interpretation, which can lead to misunderstanding (Hayakawa & Hayakawa, 1990). When shared referents are important, we should try to use language that is lower on the ladder of abstraction. Being intentionally concrete is useful when giving directions, for example, and can help prevent misunderstanding. We sometimes intentionally use abstract language. Since abstract language is often unclear or vague, we can use it as a means of testing out a potential topic (like asking a favor), offering negative feedback indirectly (to avoid hurting someone’s feelings or to hint), or avoiding the specifics of a topic.

Knowing more about the role that abstraction plays in the generation of meaning can help us better describe and define the words we use. As we learned earlier, denotative definitions are those found in the dictionary—the official or agreed-on definition. Since definitions are composed of other words, people who compile dictionaries take for granted that there is a certain amount of familiarity with the words they use to define another word—otherwise we would just be going in circles. One challenge we face when defining words is our tendency to go up the ladder of abstraction rather than down (Hayakawa & Hayakawa, 1990). For example, if I asked you to define the word blue, you’d likely say it’s a color. To define it more clearly, by going down the ladder of abstraction, you could say, “It’s the color of Frank Sinatra’s eyes,” or “It’s what the sky looks like on a clear day.” People often come to understanding more quickly when a definition is descriptive and/or ties into their personal experiences.

Although it is often helpful to use specific words and reference points down the ladder of abstraction, there are times when those references won’t be recognized by broad or diverse audiences. Jargon refers to specialized words used by a certain group or profession. Since jargon is specialized, it is often difficult to relate to a diverse audience and should therefore be limited when speaking to people from outside the group—or should at least be clearly defined when it is used.

Communication accommodation theory is a theory that explores why and how people modify their communication to fit situational, social, cultural, and relational contexts (Giles, Taylor, & Bourhis, 1973). Within communication accommodation, conversational partners may use convergence, meaning a person makes their communication more like another person’s. People who are accommodating in their communication style are seen as more competent, which illustrates the benefits of communicative flexibility. In order to be flexible, of course, people have to be aware of and monitor their own and others’ communication patterns. Conversely, conversational partners may use divergence, meaning a person uses communication to emphasize the differences between their conversational partner and themself.

Convergence and divergence can take place within the same conversation and may be used by one or both conversational partners. Convergence functions to make others feel at ease, to increase understanding, and to enhance social bonds. Divergence may be used to intentionally make another person feel unwelcome or perhaps to highlight a personal, group, or cultural identity. For example, many Black women use certain verbal communication patterns when communicating with other Black women as a way to highlight their racial identity and create group solidarity. In situations where multiple races interact, the women usually don’t use those same patterns, instead accommodating the language patterns of the larger group.

While communication accommodation might involve anything from adjusting how fast or slow you talk to how long you speak during each turn, code-switching refers to changes in accent, dialect, or language (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). There are many reasons that people might code-switch. For example, if a Southerner thinks their accent is leading others to form unfavorable impressions, they can consciously change their accent with much practice and effort. Once their ability to speak without their Southern accent is honed, they may be able to switch very quickly between their native accent when speaking with friends and family and their modified accent when speaking in professional settings. Additionally, people who work or live in multilingual settings may code-switch many times throughout the day, or even within a single conversation.

Using Words Affectively

Affective language refers to language used to express a person’s feelings and create similar feelings in another person (Hayakawa & Hayakawa, 1990). Affective language can be intentionally used in relational contexts to create or enhance interpersonal bonds and can also be effectively employed in public speaking to engage an audience and motivate them in particular ways. We also use affective language spontaneously and less intentionally. People who “speak from the heart” connect well with others due to the affective nature of their words. Sometimes people become so filled with emotion that they have to express it, and these exclamations usually arouse emotions in others. Hearing someone exclaim, “I’m so happy!” can evoke similar feelings of joy, while hearing someone exclaim, “Why me!?” while sobbing conjures up similar feelings of sadness and frustration. There are also specific linguistic devices that facilitate affective communication.

Figurative Language

When people say something is a “figure of speech,” they are referring to a word or phrase that deviates from expectations in some way in meaning or usage (Yaguello, 1998). Figurative language is the result of breaking semantic rules, but in a way that typically enhances meaning or understanding rather than diminishes it. To understand figurative language, a person has to be familiar with the semantic rules of a language and also with social norms and patterns within a cultural and/or language group, which often makes it difficult for non-native speakers to grasp. Figurative language has the ability to convey much meaning in fewer words, because some of the meaning lies in the context of usage (what a listener can imply by the deviation from semantic norms) and in the listener (how the listener makes meaning by connecting the figurative language to his or her personal experience). Some examples of figurative speech include simile, metaphor, and personification.

A simile is a direct comparison of two things using the words like or as. Similes can be very explicit for the purpose of conveying a specific meaning and can help increase clarity and lead people to personally connect to a meaning since they must visualize the comparison in their minds. For example, Forrest Gump’s famous simile, “Life is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re gonna get,” conjures up feelings of uncertainty and excitement. More direct similes like “I slept like a baby” and “That bread was hard as a rock” do not necessarily stir the imagination but still offer an alternative way of expressing something.

A metaphor is an implicit comparison of two things that are not alike or are not typically associated. Metaphors become meaningful as people realize the speaker’s purpose for relating the two seemingly disparate ideas. In 1946, just after World War II ended, Winston Churchill stated the following in a speech: “An iron curtain has descended across the continent of Europe.” Even though people knew there was no literal heavy metal curtain that had been lowered over Europe, the concepts of iron being strong and impenetrable and curtains being a divider combined to create a stirring and powerful image of a continent divided by the dark events of the previous years (Carpenter, 1999). Some communication scholars argue that metaphors serve a much larger purpose and function to structure our human thought processes (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). The metaphor “time is money” doesn’t just represent an imaginative connection; it shapes our social realities. We engage in specific actions that “save time,” “spend time,” or “waste time” because we have been socialized to see time as a resource.

Many metaphors spring from our everyday experiences. For example, many objects have been implicitly compared to human body parts (e.g., a clock, which we say has a face and hands). Personification refers to the attribution of human qualities or characteristics of other living things to nonhuman objects or abstract concepts. This can be useful when trying to make something abstract more concrete and can create a sense of urgency or “realness” out of something that is hard for people to conceive. Personification has been used successfully in public awareness campaigns because it allows people to identify with something they think might not be relevant to them, as you can see in the following examples: “Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a sleeping enemy that lives in many people and will one day wake up and demand your attention if you do not address it now.” “Crystal meth is stalking your children whether you see it or not. You never know where it’s hiding.”

Evocative Language

Vivid language captures people’s attention and their imagination by conveying emotions and action. Think of the array of mental images that a poem or a well-told story from a friend can conjure up. Evocative language can also lead us to have physical reactions. Words like shiver and heartbroken can lead people to remember previous physical sensations related to the word. As a speaker, there may be times when evoking a positive or negative reaction could be beneficial. Evoking a sense of calm could help you talk a friend through troubling health news. Evoking a sense of agitation and anger could help you motivate an audience to action. When we are conversing with a friend or speaking to an audience, we are primarily engaging others’ visual and auditory senses. Evocative language can help your conversational partner or audience members feel, smell, or taste something as well as hear it and see it. Good writers know how to use words effectively and affectively. The rich fantasy worlds conceived in Star Trek, The Lord of the Rings, and Twilight show the power of figurative and evocative language to capture our attention and our imagination.

Some words are so evocative that their usage violates the social norms of appropriate conversations. Although we could use such words to intentionally shock people, we can also use euphemisms, or indirect and less evocative references to words or ideas that are deemed inappropriate to discuss directly. We have many euphemisms for things like sex and death (Allan & Burridge, 2006). While euphemisms can be socially useful and creative, they can also lead to misunderstanding and problems in cases where more direct communication is warranted despite social conventions.

Using Words Ethically

We learned in Chapter 1 that communication is irreversible. As the National Communication Association’s “Credo for Ethical Communication” states, we should be held accountable for the long- and short-term effects of our communication. The way we talk, the words we choose to use, and the actions we take after we are done speaking are all important aspects of communication ethics. Knowing that language can have real effects for people increases our need to be aware of the ethical implications of what we say. In this section, we will focus on civility and accountability.

Civility

Our strong emotions regarding our own beliefs, attitudes, and values can sometimes lead to incivility in our verbal communication. Incivility occurs when a person deviates from established social norms and can take many forms, including insults, bragging, bullying, gossiping, swearing, deception, and defensiveness, among others (Miller, 2001). Some people lament that we live in a time when civility is diminishing, but since standards and expectations for what is considered civil communication have changed over time, this isn’t the only time such claims have been made (Miller, 2001).

Some journalists, media commentators, and scholars have argued that the “flaming” that happens on comment sections of websites and blogs is a type of verbal incivility that presents a threat to our democracy (Brooks & Greer, 2007). Other scholars of communication and democracy have not as readily labeled such communication “uncivil” (Cammaerts, 2009). It has long been argued that civility is important for the functioning and growth of a democracy (Kingwell, 1995). But in the new digital age of democracy where technologies like Twitter and Facebook have started democratic revolutions, some argue that the Internet and other new media have opened spaces in which people can engage in cyberactivism and express marginal viewpoints that may otherwise not be heard (Dahlberg, 2007). In any case, researchers have identified several aspects of language use online that are typically viewed as negative: name-calling, character assassination, and the use of obscene language (Sobieraj & Berry, 2011). So what contributes to such uncivil behavior—online and offline? The following are some common individual and situational influences that may lead to breaches of civility (Miller, 2001):

- Individual differences. Some people differ in their interpretations of civility in various settings, and some people have personality traits that may lead to actions deemed uncivil on a more regular basis.

- Ignorance. In some cases, especially in novel situations involving uncertainty, people may not know what social norms and expectations are.

- Lack of skill. Even when we know how to behave, we may not be able to do it. Such frustrations may lead a person to revert to undesirable behavior such as engaging in personal attacks during a conflict because they don’t know what else to do.

- Lapse of control. Self-control is not an unlimited resource. Even when people know how to behave and have the skill to respond to a situation appropriately, they may not do so. Even people who are careful to monitor their behavior have occasional slipups.

- Negative intent. Some people, in an attempt to break with conformity or challenge societal norms, or for self-benefit (publicly embarrassing someone in order to look cool or edgy), are openly uncivil. Such behavior can also result from mental or psychological stresses or illnesses.

Accountability

The complexity of our verbal language system allows us to present inferences as facts and mask judgments within seemingly objective or oblique language. As an ethical speaker and a critical listener, it is important to be able to distinguish between facts, inferences, and judgments (Hayakawa & Hayakawa, 1990). Inferences are conclusions based on thoughts or speculation, but not direct observation. Facts are conclusions based on direct observation or group consensus. Judgments are expressions of approval or disapproval that are subjective and not verifiable.

Linguists have noted that a frequent source of miscommunication is inference-observation confusion, or the misperception of an inference (conclusion based on limited information) as an observation (an observed or agreed-on fact) (Haney, 1992). We can see the possibility for such confusion in the following example: If a student posts on a professor-rating site the statement “This professor grades unfairly and plays favorites,” then they are presenting an inference and a judgment that could easily be interpreted as a fact. Using some of the strategies discussed earlier for speaking clearly can help present information in a more ethical way—for example, by using concrete and descriptive language and owning emotions and thoughts through the use of “I language.” To help clarify the message and be more accountable, the student could say, “I worked for three days straight on my final paper and only got a C,” which we will assume is a statement of fact. This could then be followed up with “But my friend told me she only worked on hers the day before it was due and she got an A. I think that’s unfair and I feel like my efforts aren’t recognized by the professor.” Of the last two statements, the first states what may be a fact (note, however, that the information is secondhand rather than directly observed) and the second states an inferred conclusion and expresses an owned thought and feeling. Sometimes people don’t want to mark their statements as inferences because they want to believe them as facts. In this case, the student may have attributed her grade to the professor’s “unfairness” to cover up or avoid thoughts that her friend may be a better student in this subject area, a better writer, or a better student in general. Distinguishing between facts, inferences, and judgments, however, allows your listeners to better understand your message and judge the merits of it, which makes us more accountable and therefore more ethical speakers.

Key Concepts: Engaging Language

Employing language in an engaging way requires some effort for most people in terms of learning the rules of a language system, practicing, and expanding your vocabulary and expressive repertoire. Only milliseconds pass before a thought is verbalized and “out there” in the world. Since we’ve already learned that we have to be accountable for the short- and long-term effects of our communication, we know being able to monitor our verbal communication and follow the old adage to “think before we speak” is an asset. Using language for effect is difficult, but it can make your speech unique whether it is in a conversation or in front of a larger audience. Aside from communicating ideas, speech also leaves lasting impressions. The following are some tips for using words well that can apply to various settings but may be particularly useful in situations where one person is trying to engage the attention of an audience.

- Use concrete words to make new concepts or ideas relevant to the experience of your listeners.

- Use an appropriate level of vocabulary. It is usually obvious when people are trying to speak at a level that is out of their comfort zone, which can hurt credibility.

- Avoid public speeches that are too rigid and unnatural. Even though public speaking is more formal than conversation, it is usually OK to use contractions and personal pronouns. Not doing so would make the speech awkward and difficult to deliver since it is not a typical way of speaking.

- Avoid “bloating” your language by using unnecessary words. Don’t say “it is ever apparent” when you can just say “it’s clear.”

- Use vivid words to paint mental images for your listeners. Take them to places outside of the immediate setting through rich description.

- Use repetition to emphasize key ideas.

- When giving a formal speech that you have time to prepare for, record your speech and listen to your words. Have your outline with you and take note of areas that seem too bland, bloated, or confusing and then edit them before you deliver the speech.

Discussion Questions:

- What are some areas of verbal communication that you can do well on? What are some areas of verbal communication that you could improve?

- Think of a time when a speaker’s use of language left a positive impression on you. What concepts from this chapter can you apply to their verbal communication to help explain why it was so positive?

- Think of a time when a speaker’s use of language left a negative impression on you. What concepts from this chapter can you apply to their verbal communication to help explain why it was so negative?

References

Abram, D. (1997). Spell of the sensuous: Perception and language in a more-than-human world. Vintage Books.

Allan, K., & Burridge, K. (2006). Forbidden words: Taboo and the censoring of language. Cambridge University Press.

Brooks, D. J., & Greer, J. G. (2007). Beyond negativity: The effects of incivility on the electorate. American Journal of Political Science, 51(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00233.x.

Brown, G., & Edmunds, S. (2019). Explaining. In O. Hargie (Ed.), The handbook of communication skills (pp. 183–215). Routledge.

Cammaerts, B. (2009). Radical pluralism and free speech in online public spaces: The case of North Belgian extreme right discourses. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 12(6), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877909342479.

Carpenter, R. H. (1999). Choosing powerful words: Eloquence that works. Allyn and Bacon.

Crystal, D. (2005). How language works: How babies babble, words change meaning, and languages live or die. Overlook Press.

Dahlberg, L. (2007). Rethinking the fragmentation of the cyberpublic: From consensus to contestation. New Media & Society, 9(5), 827–847. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444807081228.

de Saussure, F. (1974). Course in general linguistics (W. Baskin, Trans.). Fontana/Collins. (Original work published in 1916).

Eco, U. (1976). A theory of semiotics. Indiana University Press.

Giles, H., Taylor, D. M., & Bourhis, R. (1973). Towards a theory of interpersonal accommodation through language: Some Canadian data. Language and Society, 2(2), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500000701.

Haney, W. V. (1992). Communication and interpersonal relations (6th ed.). Irwin.

Hargie, O. (2011). Skilled interpersonal interaction: Research, theory, and practice (5th ed.). Routledge.

Hayakawa, S. I., & Hayakawa, A. R. (1990). Language in thought and action (5th ed.). Harcourt Brace.

Kingwell, M. (1995). A civil tongue: Justice, dialogue, and the politics of pluralism. Pennsylvania State University Press.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

Martin, J. N., & Nakayama, T. K. (2010). Intercultural communication in contexts (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

McCornack, S. (2007). Reflect and relate: An introduction to interpersonal communication. Bedford/St. Martin’s.

McKay, M., Davis, M., & Fanning, P. (1995). Messages: Communication skills book (2nd ed.). New Harbinger Publications.

Miller, R. S. (2001). Breaches of propriety. In R. M. Kowalski (Ed.), Behaving badly: Aversive behaviors in interpersonal relationships (pp. 29–58). American Psychological Association.

Sobieraj, S., & Berry. J. (2011). From incivility to outrage: Political discourse in blogs, talk radio, and cable news. Political Communication, 28(1), 19–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2010.542360.

Yaguello, M. (1998). Language through the looking glass: Exploring language and linguistics. Oxford University Press.

Credits

Chapter 3 was adapted, remixed, and curated from Chapter 3 of Communication in the Real World: An Introduction to Communication Studies, a work produced and distributed under a CC BY-NC-SA license in 2013 by a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution.