Learning Objective

- Understand how to be ethical, avoid plagiarism, and use reputable sources in your writing.

Unlike writing for personal or academic purposes, your business writing will help determine how well your performance is evaluated in your job. Whether you are writing for colleagues within your workplace or outside vendors or customers, you will want to build a solid, well-earned favorable reputation for yourself with your writing. Your goal is to maintain and enhance your credibility, and that of your organization, at all times.

Make sure as you start your investigation that you always question the credibility of the information. Sources may have no reviews by peers or editor, and the information may be misleading, biased, or even false. Be a wise information consumer.

Business Ethics

Many employers have a corporate code of ethics; even if your employer does not, it goes without saying that there are laws governing how the company can and cannot conduct business. Some of these laws apply to business writing. As an example, it would be not only unethical but also illegal to send out a promotional letter announcing a special sale on an item that ordinarily costs $500, offering it for $100, if in fact you have only one of this item in inventory. When a retailer does this, the unannounced purpose of the letter is to draw customers into the store, apologize for running out of the sale item, and urge them to buy a similar item for $400. Known as “bait and switch,” this is a form of fraud and is punishable by law.

Let’s return to our previous newsletter scenario to examine some less clear-cut issues of business ethics. Suppose that, as you confer with your president and continue your research on newsletter vendors, you remember that you have a cousin who recently graduated from college with a journalism degree. You decide to talk to her about your project. In the course of the conversation, you learn that she now has a job working for a newsletter vendor. She is very excited to hear about your firm’s plans and asks you to make her company “look good” in your report.

You are now in a situation that involves at least two ethical questions:

- Did you breach your firm’s confidentiality by telling your cousin about the plan to start sending a monthly newsletter?

- Is there any ethical way you can comply with your cousin’s request to show her company in an especially favorable light?

On the question of confidentiality, the answer may depend on whether you signed a confidentiality agreement as a condition of your employment at the accounting firm, or whether your president specifically told you to keep the newsletter plan confidential. If neither of these safeguards existed, then your conversation with your cousin would be an innocent, unintentional and coincidental sharing of information in which she turned out to have a vested interest.

As for representing her company in an especially favorable light—you are ethically obligated to describe all the candidate vendors according to whatever criteria your president asked to see. The fact that your cousin works for a certain vendor may be an asset or a liability in your firm’s view, but it would probably be best to inform them of it and let them make that judgment.

As another example of ethics in presenting material, let’s return to the skydiving scenario we mentioned earlier. Because you are writing a promotional letter whose goal is to increase enrollment in your skydiving instruction, you may be tempted to avoid mentioning information that could be perceived as negative. If issues of personal health condition or accident rates in skydiving appear to discourage rather than encourage your audience to consider skydiving, you may be tempted to omit them. But in so doing, you are not presenting an accurate picture and may mislead your audience.

Even if your purpose is to persuade, deleting the opposing points presents a one-sided presentation. The audience will naturally consider not only what you tell them but also what you are not telling them, and will raise questions. Instead, consider your responsibility as a writer to present information you understand to be complete, honest, and ethical. Lying by omission can also expose your organization to liability. Instead of making a claim that skydiving is completely safe, you may want to state that your school complies with the safety guidelines of the United States Parachute Association. You might also state how many jumps your school has completed in the past year without an accident.

Giving Credit to Your Sources

You have photos of yourself jumping but they aren’t very exciting. Since you are wearing goggles to protect your eyes and the image is at a distance, who can really tell if the person in the picture is you or not? Why not find a more exciting photo on the Internet and use it as an illustration for your letter? You can download it from a free site and the “fine print” at the bottom of the Web page states that the photos can be copied for personal use.

Not so fast—do you realize that a company’s promotional letter does not qualify as personal use? The fact is that using the photo for a commercial purpose without permission from the photographer constitutes an infringement of copyright law; your employer could be sued because you decided to liven up your letter by taking a shortcut. Furthermore, falsely representing the more exciting photo as being your parachute jump will undermine your company’s credibility if your readers happen to find the photo on the Internet and realize it is not yours.

Just as you wouldn’t want to include an image more exciting than yours and falsely state that it is your jump, you wouldn’t want to take information from sources and fail to give them credit. Whether the material is a photograph, text, a chart or graph, or any other form of media, taking someone else’s work and representing it as your own is plagiarism. Plagiarism is committed whether you copy material verbatim, paraphrase its wording, or even merely take its ideas—if you do any of these things—without giving credit to the source.

This does not mean you are forbidden to quote from your sources. It’s entirely likely that in the course of research you may find a perfect turn of phrase or a way of communicating ideas that fits your needs perfectly. Using it in your writing is fine, provided that you credit the source fully enough that your readers can find it on their own. If you fail to take careful notes, or the sentence is present in your writing but later fails to get accurate attribution, it can have a negative impact on you and your organization. That is why it is important that when you find an element you would like to incorporate in your document, in the same moment as you copy and paste or make a note of it in your research file, you need to note the source in a complete enough form to find it again.

Giving credit where credit is due will build your credibility and enhance your document. Moreover, when your writing is authentically yours, your audience will catch your enthusiasm, and you will feel more confident in the material you produce. Just as you have a responsibility in business to be honest in selling your product of service and avoid cheating your customers, so you have a responsibility in business writing to be honest in presenting your idea, and the ideas of others, and to avoid cheating your readers with plagiarized material.

Challenges of Online Research

Earlier in the chapter we have touched on the fact that the Internet is an amazing source of information, but for that very reason, it is a difficult place to get information you actually need. In the early years of the Internet, there was a sharp distinction between a search engine and a Web site. There were many search engines competing with one another, and their home pages were generally fairly blank except for a search field where the user would enter the desired search keywords or parameters. There are still many search sites, but today, a few search engines have come to dominate the field, including Google and Yahoo! Moreover, most search engines’ home pages offer a wide range of options beyond an overall Web search; buttons for options such as news, maps, images, and videos are typical. Another type of search engine performs a metasearch, returning search results from several search engines at once.

When you are looking for a specific kind of information, these relatively general searches can still lead you far away from your desired results. In that case, you may be better served by an online dictionary, encyclopedia, business directory, or phone directory. There are also specialized online databases for almost every industry, profession, and area of scholarship; some are available to anyone, others are free but require opening an account, and some require paying a subscription fee. For example, http://www.zillow.com allows for in-depth search and collation of information concerning real estate and evaluation, including the integration of public databases that feature tax assessments and ownership transfers. Table 5.2 “Some Examples of Internet Search Sites” provides a few examples of different kinds of search sites.

Table 5.2 Some Examples of Internet Search Sites

| Description | URL |

|---|---|

| General Web searches that can also be customized according to categories like news, maps, images, video | |

| Metasearch engines | |

| Dictionaries and encyclopedias | |

| Very basic information on a wide range of topics | |

| To find people or businesses in white pages or yellow pages listings | |

| Specialized databases—may be free, require registration, or require a paid subscription |

At the end of this chapter, under “Additional Resources,” you will find a list of many Web sites that may be useful for business research.

Evaluating Your Sources

One aspect of Internet research that cannot be emphasized enough is the abundance of online information that is incomplete, outdated, misleading, or downright false. Anyone can put up a Web site; once it is up, the owner may or may not enter updates or corrections on a regular basis. Anyone can write a blog on any subject, whether or not that person actually has any expertise on that subject. Anyone who wishes to contribute to a Wikipedia article can do so—although the postings are moderated by editors who have to register and submit their qualifications. In the United States, the First Amendment of the Constitution guarantees freedom of expression. This freedom is restricted by laws prohibiting libel (false accusations against a person) and indecency, especially child pornography, but those laws are limited in scope and sometimes difficult to enforce. Therefore, it is always important to look beyond the surface of a site to assess who sponsors it, where the information displayed came from, and whether the site owner has a certain agenda.

When you write for business and industry you will want to draw on reputable, reliable sources—printed as well as electronic ones—because they reflect on the credibility of the message and the messenger. Analyzing and assessing information is an important skill in the preparation of writing, and here are six main points to consider when evaluating a document, presentation, or similar source of information1. In general, documents that represent quality reasoning have the following traits:

- A clearly articulated purpose and goal

- A question, problem, or issue to address

- Information, data, and evidence that is clearly relevant to the stated purpose and goals

- Inferences or interpretations that lead to conclusions based on the presented information, data, and evidence

- A frame of reference or point of view that is clearly articulated

- Assumptions, concepts, and ideas that are clearly articulated

An additional question that is central to your assessment of your sources is how credible the source is. This question is difficult to address even with years of training and expertise. You may have heard of academic fields called “disciplines,” but may not have heard of each field’s professors called “disciples.” Believers, keepers of wisdom, and teachers of tomorrow’s teachers have long played a valuable role establishing, maintaining, and perpetuating credibility. Academics have long cultivated an understood acceptance of the role of objective, impartial use of the scientific method to determine validity and reliability. But as research is increasingly dependent on funding, and funding often brings specific points of view and agendas with it, pure research can be—and has been—compromised. You can no longer simply assume that “studies show” something without awareness of who conducted the study, how was it conducted, and who funded the effort. This may sound like a lot of investigation and present quite a challenge, but again it is worth the effort.

Information literacy is an essential skill set in the process of writing. As you learn to spot key signs of information that will not serve to enhance your credibility and contribute to your document, you can increase your effectiveness as you research and analyze your resources. For example, if you were researching electronic monitoring in the workplace, you might come upon a site owned by a company that sells workplace electronic monitoring systems. The site might give many statistics illustrating what percentage of employers use electronic monitoring, what percentage of employees use the Internet for nonwork purposes during work hours, what percentage of employees use company e-mail for personal messages, and so on. But the sources of these percentage figures may not be credited. As an intelligent researcher, you need to ask yourself, did the company that owns the site perform its own research to get these numbers? Most likely it did not—so why are the sources not cited? Moreover, such a site would be unlikely to mention any court rulings about electronic monitoring being unnecessarily invasive of employees’ privacy. Less biased sources of information would be the American Management Association, the U.S. Department of Labor, and other not-for-profit organizations that study workplace issues.

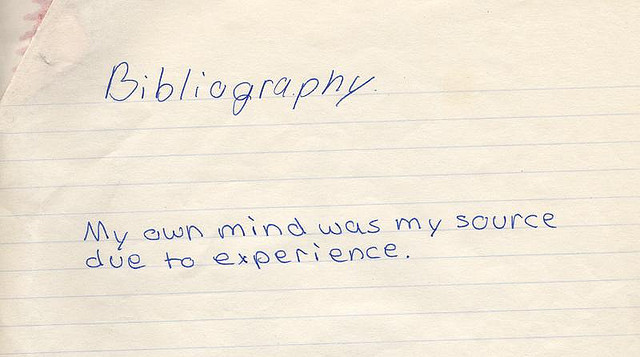

Figure 5.2

Discover something new as you research, but always evaluate the source.

papertrix – bibliography – CC BY-NC 2.0.

The Internet also encompasses thousands of interactive sites where readers can ask and answer questions. Some sites, like Askville by Amazon.com, WikiAnswers, and Yahoo! Answers, are open to almost any topic. Others, like ParentingQuestions and WebMD, deal with specific topics. Chat rooms on bridal Web sites allow couples who are planning a wedding to share advice and compare prices for gowns, florists, caterers, and so on. Reader comment sites like Newsvine facilitate discussions about current events. Customer reviews are available for just about everything imaginable, from hotels and restaurants to personal care products, home improvement products, and sports equipment. The writers of these customer reviews, the chat room participants, and the people who ask and answer questions on many of these interactive sites are not experts, nor do they pretend to be. Some may have extreme opinions that are not based in reality. Then, too, it is always possible for a vendor to “plant” favorable customer reviews on the Internet to make its product look good. Although the “terms of use” which everyone registering for interactive sites must agree to usually forbid the posting of advertisements, profanity, or personal attacks, some sites do a better job than others in monitoring and deleting such material. Nevertheless, if your business writing project involves finding out how the “average person” feels about an issue in the news, or whether a new type of home exercise device really works as advertised, these comment and customer review sites can be very useful indeed.

It may seem like it’s hard work to assess your sources, to make sure your information is accurate and truthful, but the effort is worth it. Business and industry rely on reputation and trust (just as we individuals do) in order to maintain healthy relationships. Your document, regardless of how small it may appear in the larger picture, is an important part of that reputation and interaction.

Key Takeaway

Evaluating your sources is a key element of the preparation process in business writing. To avoid plagiarism, always record your sources so that you can credit them in your writing.

Exercises

- Before the Internet improved information access, how did people find information? Are the strategies they used still valid and how might they serve you as a business writer? Interview several people who are old enough to have done research in the “old days” and report your findings.

- Visit the Web site of the United States Copyright Office at http://www.copyright.gov. Find something on the Web site that you did not know before reviewing it and share it with your classmates.

- On the United States Copyright Office Web site at http://www.copyright.gov view the multimedia presentation for students and teachers, “Taking the Mystery out of Copyright.” Download the “Copyright Basics” document and discuss it with your class.

- Look over the syllabus for your business communication course and assess the writing assignments you will be completing. Is all the information you are going to need for these assignments available in electronic form? Why or why not?

- Does the fact that Internet search results are often associated with advertising influence your research and investigation? Why or why not? Discuss with a classmate.

- Find an example of a bogus or less than credible Web site. Indicate why you perceive it to be untrustworthy, and share it with your classmates.

- Visit the parody Web site The Onion at http://www.theonion.com and find one story that you think has plausible or believable elements. Share your findings with the class.

1Adapted from Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2007). The miniature guide to critical thinking: Concepts and tools. Dillon Beach, CA: The Foundation for Critical Thinking Press.