Learning Objectives

- Define Hofstede’s five dimensions of cultural consequences; power distance, individualism, collectivism, uncertainty avoidance and masculinity & femininity.

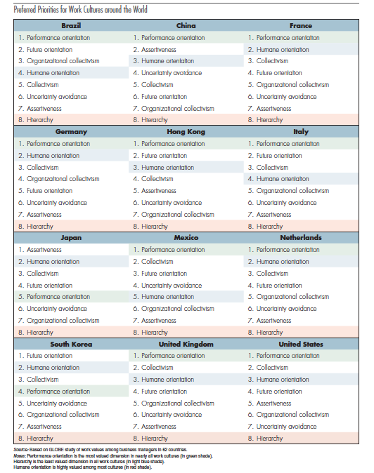

- Compare The Globe’s study of managers from 62 countries; individualism, collectivism, organizational collectivism, hierarchy, performance orientation, future orientation, assertiveness, humane orientation, uncertainty avoidance.

Divergent Cultural Characteristics

Hofstede’s Five Dimensions

Power Distance – how do we feel about those in power? In cultures with low power distance, people are likely to expect that power is distributed rather equally, and are furthermore also likely to accept that power is distributed to less powerful individuals. As opposed to this, people in high power distance cultures will likely both expect and accept inequality and steep hierarchies. (BusinessMate.org, 2014)

Uncertainty Avoidance – How will they adapt to change and uncertainty? Uncertainty avoidance is referring to lack of tolerance for ambiguity and need for formal rules and policies. This dimension measures the extent to which people feel threatened by ambiguous situations. These uncertainties and ambiguities may be handled by an introduction of formal rules or policies, or by a general acceptance of ambiguity in the organizational life. The majority of people living in cultures with a high degree of uncertainty avoidance are likely to feel uncomfortable in uncertain and ambiguous situations. People living in cultures with low degree of uncertainty avoidance, are likely to thrive in more uncertain and ambiguous situations and environments. (BusinessMate.org, 2014)

Individualism vs. Collectivism – which is valued more? In individualistic cultures people are expected to portray themselves as individuals, who seek to accomplish individual goals and needs. In collectivistic cultures, people have greater emphasis on the welfare of the entire group to which the individual belongs, where individual’s wants, needs and dreams are often set aside for the common good. (BusinessMate.org, 2014)

Masculinity vs. Femininity – What is male/female role? These values concern that extent on emphasis on masculine work related goals and assertiveness (earnings, advancement, title, respect, et.), as opposed to more personal and humanistic goals (friendly working climate, cooperation, nurturance etc.) (BusinessMate.org, 2014)

Time Orientation – short or long term? Long-Term Orientation is fifth dimension, which was added after the original four dimensions. This dimension was identified by Michael Bond and was initially called Confucian dynamism. Geert Hofstede added this dimension to his framework, and labeled this dimension long vs. short-term orientation. The consequences for work related values and behavior springing from this dimension is rather hard to describe, but some characteristics are described below. (BusinessMate.org, 2014)

Long Term Orientation:

- Acceptance of that business results may take time to achieved

- The employee wishes a long relationship with the company

Short Term Orientation:

- Results and achievements are set, and can be reached within timeframe

- The employee will potentially change employer very often

| Country | Power Distance | Individualism/ Collectivism | Uncertainty Avoidance | Masculinity/Femininity |

| Argentina | 49 | 46 | 86 | 56 |

| Australia | 36 | 90 | 51 | 61 |

| Brazil | 69 | 38 | 76 | 61 |

| Canada[1] | 39 | 80 | 48 | 52 |

| Chile | 63 | 23 | 86 | 28 |

| China | 80 | 20 | 30 | 66 |

| Colombia | 67 | 13 | 80 | 64 |

| Denmark | 18 | 74 | 23 | 16 |

| France | 68 | 71 | 86 | 43 |

| Germany | 35 | 67 | 65 | 66 |

| Greece | 60 | 35 | 112 | 57 |

| Indonesia | 78 | 14 | 48 | 46 |

| India | 77 | 48 | 40 | 56 |

| Iran | 59 | 41 | 59 | 43 |

| Israel | 13 | 54 | 81 | 47 |

| Italy | 50 | 76 | 75 | 70 |

| Japan | 54 | 46 | 92 | 95 |

| Korea (South) | 60 | 18 | 85 | 39 |

| Malaysia | 104 | 26 | 36 | 50 |

| Mexico | 81 | 30 | 82 | 69 |

| Netherlands | 38 | 80 | 53 | 14 |

| Phillippines | 94 | 32 | 44 | 64 |

| Poland | 68 | 60 | 93 | 64 |

| Portugal | 63 | 27 | 104 | 31 |

| Russia | 93 | 39 | 95 | 36 |

| Singapore | 74 | 20 | 8 | 48 |

| Spain | 57 | 51 | 86 | 42 |

| Sweden | 31 | 71 | 29 | 5 |

| United Kingdom | 35 | 89 | 35 | 66 |

| United States | 40 | 91 | 46 | 62 |

| Mean | 58.4 | 49.0 | 64.5 | 50.2 |

| Median | 60 | 46 | 70 | 51 |

Source: Geert Hofstede, Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values, 1980, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

The Globe Group Eight Dimensions

Individualism & Collectivism

This dimension deals with the level of independence and interdependence that people in society possess and encourage. Individualism refers to a mind-set that prioritizes independence more highly than interdependence, emphasizing individual goals over group goals, and valuing choice more than obligation. By contrast, collectivism refers to a mind-set that prioritizes interdependence more highly than independence, emphasizing group goals over individual goals, and valuing obligation more than choice.

Individualists view themselves as distinct and separate from their family members, friends, and colleagues. They pursue their own dreams and goals, even when it means spending less time with family members and friends. They also leave relationships when they are no longer mutually satisfying, beneficial, or convenient. Decision making tends to be based on an individual’s needs. On the other hand, collectivists view themselves as interdependent—forming an identity inseparable from that of their family members, friends, and other groups. They tend to follow the perceived dreams and goals of the group as a matter of duty and obligation, even when it means sacrificing their own hopes and ambitions.

Egalitarianism & Hierarchy

All cultures develop norms for how power is distributed. In egalitarian cultures, people tend to distribute and share power evenly, minimize status differences, and minimize special privileges and opportunities for people just because they have higher authority. In hierarchical cultures, people expect power differences, follow leaders without questioning them, and feel comfortable with leaders receiving special privileges and opportunities. Power tends to be concentrated at the top. In egalitarian organizations, leaders avoid command-and-control approaches and lead with participatory and open management styles. Competence is highly valued in positions of authority. People of all ranks are encouraged to voice their opinions. By contrast, in hierarchical organizations, leaders expect employees to fall in line with their policies and decisions by virtue of their authority. Employees are discouraged from openly challenging leaders.

Performance Orientation (PO)

Is “the extent to which a community encourages and rewards innovation, high standards, and performance improvement.” Of all cultural dimensions, societies cherish this one the most, especially in business. Yet many cultures are still developing a performance orientation. 37 To some degree, the distinctions between high PO and low PO cultures are captured in the phrase living to work versus working to live. The cultures of Far Eastern Asia, Western Europe, and North America are particularly high in performance orientation. For example, professionals in higher PO cultures often perceive members of lower PO cultures as not prioritizing results, accountability, and deadlines. By contrast, members of lower PO cultures often perceive members of higher PO cultures as impatient and even obsessed with short-term results. Some cultures that are midrange PO cultures such as China and India are rapidly developing PO orientations in work culture. Each of these countries has implemented major economic reforms in recent decades and is achieving stunning economic growth. These countries increasingly have companies and workforces that adopt norms and policies promoting innovation, improvement, and accountability systems.

Future Orientation (FO)

Involves the degree to which cultures are willing to sacrifice current wants to achieve future needs. Cultures with low FO (or present-oriented cultures) tend to enjoy being in the moment and spontaneity. They are less anxious about the future and often avoid the planning and sacrifices necessary to reach future goals.

By contrast, cultures with high FO are imaginative about the future and have the discipline to carefully plan for and sacrifice current needs and wants to reach future goals. In future-oriented societies, many organizations create long-term strategies and business plans. Furthermore, they use these strategies and plans to guide their short-term business activities. By contrast, in present-oriented societies, organizations are less likely to develop clear long-term strategies and business plans. Moreover, they rarely focus short-term activities on long-term plans, even when they exist. Future orientation within organizations is a strong predictor of financial performance. High FO cultures plan extensively for crises and unforeseen contingencies, whereas low FO cultures take events as they occur

Assertiveness

The level of directness in speech varies greatly across cultures, and this can lead to miscommunication, misinterpretation of motivations, and hard feelings. The cultural dimension of assertiveness deals with the level of confrontation and directness that is considered appropriate and productive. 41 Typically, North Americans and Western Europeans are the most assertive in business situations, whereas Asians tend to be less assertive. The mentality of “say it how it is,” “cut to the chase, and “don’t sugarcoat it” is emblematic of high assertiveness. Members of highly assertive cultures often view members of less-assertive cultures as timid, unenthusiastic, uncommitted, and even dishonest, since they withhold or temper their comments. On the other hand, members of less-assertive cultures often view members of highly assertive cultures as rude, non-tactful, inconsiderate, and even uncivilized.

Humane Orientation (HO)

Is “the degree to which an organization or society encourages and rewards individuals for being fair, altruistic, friendly, generous, caring, and kind.” In high HO cultures, people demonstrate that others belong and are welcome. Concern extends to all people—friends and strangers—and nature. People provide social support to each other and are urged to be sensitive to all forms of unfairness, unkindness, and discrimination. Companies and shareholders emphasize social responsibility, and leaders are expected to be generous and compassionate. In low HO cultures, the values of pleasure, comfort, and self-enjoyment take precedence over displays of generosity and kindness. People extend material, financial, and social support to a close circle of friends and family. Society members are expected to solve personal problems on their own. Companies and shareholders focus primarily on financial profits, and leaders are not expected to be generous or compassionate.

Uncertainty Avoidance (UA)

Refers to how cultures socialize members to feel in uncertain, novel, surprising, or extraordinary situations. In high UA cultures, people feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and seek orderliness, consistency, structure, and formalized procedures. People in high UA cultures often stress orderliness and consistency, even if it means sacrificing experimentation and innovation. They prefer that expectations are clear and spelled out precisely in the form of instructions and rules.

People in high UA cultures prefer tasks with sure outcomes and minimal risk. They also show more resistance to change and less tolerance for breaking rules. In low UA cultures, people feel comfortable with uncertainty. In fact, they may even thrive, since they prefer tasks that involve uncertain outcomes, calculated risks, and problem solving and experimentation. They often view rules and procedures as hindering creativity and innovation. Members of low UA cultures develop trust more quickly with people from other groups and tend to be more informal in their interactions. They also show less resistance to change, less desire to establish rules to dictate behavior, and more tolerance for breaking rules

Gender Egalitarianism

Deals with the division of roles between men and women in society. In high gender-egalitarianism cultures, men and women are encouraged to occupy the same professional roles and leadership positions. Women are included equally in decision making. In low gender-egalitarianism cultures, men and women are expected to occupy different roles in society. Typically, women have less influence in professional decision making. However, in societies where gender roles are highly distinct, women often have powerful roles in family decision making. Traditionally, nearly all cultures afforded low professional status to women. In recent decades, however, women have increasingly gained opportunity and status in many cultures. When Ghosn arrived at Nissan, only 1 percent of managers were women. He quickly made it a goal to increase the number of female managers. Now, 5 percent of the managers at Nissan are women, and the goal is to reach 10 percent in the near future.

Gender egalitarianism relates not only to equal professional opportunity for men and women, but also to expectations and customs about how men and women should communicate. Growing up, for example, Ghosn was accustomed to letting women walk through doors first. Yet, in Japan, the tradition is for men to enter doors and elevators first. Ghosn discussed how entering elevators in Japan before women remained uncomfortablefor a long time due to his expectations about gender roles.

All information about The Globe Group Eight Dimensions was taken from the below McGraw Hill Higher Education sample chapter available online. Additional information is available from this sample chapter about the Charts and details of the number categories. It is recommend reviewing for more detail. Provided by https://highered.mheducation.com/sites/dl/free/0073403199/981801/Sample_Chapter_4.pdf

Key Takeaway

Cultures have distinct orientations, values and priorities. Consider the implications of these similarities or differences on your intercultural and international business communication strategies.

Exercises

- Choose a country of interest to you (Brazil, Mexico, China, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Japan, United Kingdom or South Korea) and analyze their cultural dimensions using Hofstede’s Cultural Value Scores. What dimension is deemed highest? Lowest? Based on your findings, what communication practices do you think may be most effective when working with individuals from this country?

Power Distance Individualism/Collectivism Uncertainty Avoidance Masculinity/FemininityNow compare the same country to The Globe’s study of managers from 62 countries on preferred priorities for work cultures around the World. Are your findings similar or different? Does this change your communication strategy?Individualism/Collectivism Organizational Collectivism Hierarchy Performance OrientationFuture Orientation Assertiveness Humane orientation Uncertainty avoidance

- Interview a Business professional with International experience:

- Communication strategies – nonverbal, oral and writing

- Etiquette and customs of dominant culture they interact

- Conducting meetings

- Managing language barriers

- Adjusting to life in another country

- Negotiation style and approach

- Resolution strategies

References

Hofstede, G. (1982, 2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

House, R.J., Hanges, P.J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P.W., and Gupta, V. (2004) Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Pg. 239, 282-395, 437-512, 569, 602-653

Business Mate (2014) Great Business Resources (2014) 5 Cultural Dimensions Geert Hofstded. Business Mate.org retrieved from http://www.businessmate.org/Article.php?ArtikelId=4

Cardon (2016) Communicating Across Cultures – McGraw-Hill Higher Education. www.highered.mheducation.com/sites/dl/free/0073403199/981801/Sample_Chapter_4.Pdf

- English-speaking part ↵