Opioid analgesics are prescribed for moderate and severe pain. Before discussing morphine, the prototype opioid analgesic, and it’s antagonist, naloxone, let’s discuss the opioid epidemic in the United States, efforts to stop this epidemic, and the dangers of drug diversion.

Understanding the Opioid Epidemic

The drug overdose epidemic continues to worsen in the United States. Overdose deaths remain a leading cause of injury-related death. In the United States, drug overdoses have claimed over 932,000 lives over the past 21 years. The majority of overdose deaths involve opioids. Deaths involving synthetic opioids (i.e., illicitly made fentanyl) have increased in recent years, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.[1]

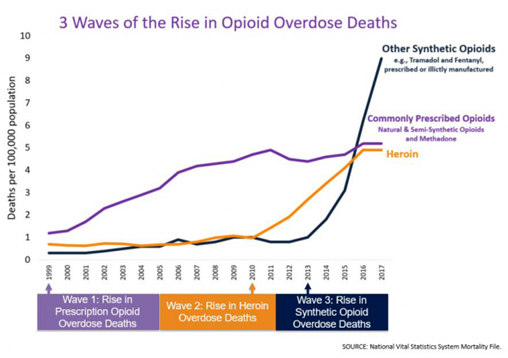

The rise in opioid overdose deaths can be outlined in three distinct waves. See Figure 10.7[2] for a graphic representation of the waves of opioid deaths.

The first wave began with increased prescribing of opioids in the 1990s, with overdose deaths involving prescription opioids (natural and semi-synthetic opioids and methadone). The second wave began in 2010 with rapid increases in overdose deaths involving heroin. The third wave began in 2013, with significant increases in overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids, especially those involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl.[3]

CDC’s Educational Campaigns

To save lives from drug overdose, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) launched four education campaigns to reach young adults (ages 18-34). The campaigns provide information that can save the lives and highlight actions the public can take to help prevent overdose. Specifically, the campaigns provide critical information about these topics[4]:

- Dangers of fentanyl

- Risks and consequences of mixing drugs

- Life-saving power of naloxone to reverse an opioid overdose

- Importance of reducing stigma to support treatment and recovery

Read more information about the CDC campaigns to stop overdose deaths.

CDC Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain

In addition to establishing educational campaigns to prevent opioid deaths, the CDC has also established new clinical practice guidelines regarding the prescription of opioids to ensure patients have access to safer, effective pain treatment while also reducing the number of people who misuse or overdose from these drugs. The CDC’s Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids – Unites States, 2022 was developed for the prescribing of opioid pain medication for patients 18 and older in primary care settings. Recommendations focus on the use of opioids in treating acute pain (pain lasting less than one month), subacute pain (pain lasting one to three months, and chronic pain (pain lasting longer than three months). This clinical practice guideline is intended to improve communication between clinicians and patients about the benefits and risks of pain treatments, including opioid therapy; improve the effectiveness and safety of pain treatment; mitigate pain; improve function and quality of life for patients with pain; and reduce risks associated with opioid pain therapy, including opioid use disorder, overdose, and death.[5] Nurses also play an important component in advocating for these outcomes.

Four key areas are covered in the CDC’s Clinical Practice Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids[6]:

- Determining whether or not to initiate opioids for pain

- Selecting opioids and determining opioid dosages

- Deciding duration of initial opioid prescription and conducting follow-up

- Assessing risk and addressing potential harms of opioid use

In addition, five guiding principles were identified[7]:

- Appropriate treatment of pain

- Flexibility to meet the care needs and clinical circumstances of each patient

- A multimodal and multidisciplinary approach to pain management

- Avoiding misapplication of the clinical practice guideline beyond its intended use

- Vigilance in attending to health inequities and ensuring access to appropriate, affordable, diversified, coordinated, and effective nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic pain treatment for all persons

Improving the way opioids are prescribed through clinical practice guidelines can ensure patients have access to safer, more effective pain treatment while also reducing the risk of opioid use disorder, overdose, and death.

Drug Diversion and Impaired Health Care Workers

Drug diversion is a potential threat to patient safety in every health care organization. Drug diversion involves the transfer of any legally prescribed controlled substance from the individual for whom it was prescribed to another person for illicit use. The most commonly diverted substances in health care facilities are opioids.

Risks to patients from drug diversion include inadequate pain relief compounded by potentially unsafe care due to the health care worker’s impaired performance.[8] More information about drug diversion and substance use disorder in health care professionals is discussed in the “Legal Foundations and National Guidelines for Safe Medication Administration” section of the “Legal/Ethical” chapter.

Opioid Medication Class

See Table 10.4 in the “Nursing Process for Analgesics and Musculoskeletal Medications” section of this chapter for a list of common opioid medications used to treat moderate to severe pain. As discussed in that section, morphine is at the top of the WHO ladder and is used to treat severe pain. It is also commonly used to treat cancer pain and for pain at end of life because there is no “ceiling effect,” meaning the higher the dose, the higher the level of analgesia. Morphine is also commonly used in patient-controlled analgesia (PCA); other medications administered via PCA include hydromorphone or fentanyl. To receive the opioid using a PCA device, the patient pushes a button, which releases a specific dose but also has a lockout mechanism to prevent an overdose.[9]

Morphine

Morphine is an example of an opioid used to treat moderate to severe pain.

Mechanism of Action: Morphine binds to opioid receptors in the CNS and alters the perception of and response to painful stimuli while producing generalized CNS depression.

Indications: Morphine is indicated for the relief of moderate to severe acute and chronic pain and for pulmonary edema.

Nursing Considerations: Morphine is safe for all ages. Use cautiously with patients with liver and renal impairment.

Side Effects/Adverse Effects: Adverse effects include respiratory depression, hypotension, light-headedness, dizziness, sedation, constipation, nausea, vomiting, and sweating.

Patient Teaching & Education: Patients should be advised regarding the risks associated with opioid analgesic use. Please see the outlined “Special Considerations” for usage below.[10]

Boxed Warning: The risk of serious adverse reactions, including slowed or difficulty breathing and death, have been reported with the combined effects of morphine with other CNS depressants. Naloxone is used to reverse opioid overdose. There is also a risk of drug abuse and dependence with morphine.

Special Considerations

Respiratory Depression: Respiratory depression is the primary risk of morphine sulfate. Respiratory depression occurs more frequently in elderly or debilitated patients and in those suffering from conditions accompanied by hypoxia, hypercapnia, or upper airway obstruction, for whom even moderate therapeutic doses may significantly decrease pulmonary ventilation.

Use morphine with extreme caution in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or cor pulmonale and in patients having a substantially decreased respiratory reserve, hypoxia, hypercapnia, or preexisting respiratory depression. In such patients, even usual therapeutic doses of morphine sulfate may increase airway resistance and decrease respiratory drive to the point of apnea. Consider alternative nonopioid analgesics and use morphine sulfate only under careful medical supervision at the lowest effective dose in such patients.

Misuse, Abuse, and Diversion of Opioids: Morphine sulfate is an opioid agonist and a Schedule II controlled substance. Such drugs are sought by drug abusers and people with addiction disorders. Diversion of Schedule II products is an act subject to criminal penalty.

Morphine can be abused in a manner similar to other opioid agonists, legal or illicit. This should be considered when prescribing or dispensing morphine sulfate in situations where there is increased risk of misuse, abuse, or diversion. Morphine may be abused by crushing, chewing, snorting, or injecting the product. These practices pose a significant risk to the abuser that could result in overdose and death.

Interactions With Alcohol and Drugs of Abuse: Morphine has addictive effects when used in conjunction with alcohol, other opioids, or illicit drugs that cause central nervous system depression because respiratory depression, hypotension, profound sedation, coma, or death may result.

Use in Head Injury and Increased Intracranial Pressure: In the presence of head injury, intracranial lesions, or a preexisting increase in intracranial pressure, the possible respiratory depressant effects of morphine and its potential to elevate cerebrospinal fluid pressure may be markedly exaggerated. Furthermore, morphine can produce effects on pupillary response and consciousness, which may obscure neurologic signs of increased intracranial pressure in patients with head injuries.

Hypotensive Effect: Morphine may cause severe hypotension in individuals unable to maintain blood pressure who have already been compromised by a depleted blood volume or drug administration of phenothiazines or general anesthetics.

Administer morphine sulfate with caution to patients in circulatory shock, as vasodilation produced by the drug may further reduce cardiac output and blood pressure.

Gastrointestinal Effects: Do not administer morphine to patients with gastrointestinal obstruction, especially paralytic ileus because morphine diminishes propulsive peristaltic waves in the gastrointestinal tract and may prolong the obstruction.

The administration of morphine sulfate may obscure the diagnosis or clinical course in patients with an acute abdominal condition.

Use in Pancreatic/Biliary Tract Disease: Use morphine with caution in patients with biliary tract disease, including acute pancreatitis, as morphine sulfate may cause spasming and diminished biliary and pancreatic secretions.

Special Risk Groups: Use morphine with caution and in reduced dosages in patients with severe renal or hepatic impairment, Addison’s disease, hypothyroidism, prostatic hypertrophy, or urethral stricture, and in elderly or debilitated patients. Exercise caution in the administration of morphine sulfate to patients with CNS depression, toxic psychosis, acute alcoholism, and delirium tremens.

All opioids may aggravate convulsions in patients with convulsive disorders, and all opioids may induce or aggravate seizures.

Driving and Operating Machinery: Caution patients that morphine sulfate could impair the mental and/or physical abilities needed to perform potentially hazardous activities such as driving a car or operating machinery.

Caution patients about the potential combined effects of morphine sulfate with other CNS depressants, including other opioids, phenothiazines, sedative/hypnotics, and alcohol.

Now let’s take a closer look at the medication grid on morphine in Table 10.7a.[11],[12],[13]

Table 10.7a Morphine Medication Grid

| Class/Subclass | Prototype/Generic | Administration Considerations | Therapeutic Effects | Adverse/Side Effects |

| Opioid Analgesic | morphine | Given parenterally and orally

Assess pain prior to and after administration Monitor respiratory status Monitor blood pressure Assess pediatric and geriatric patients frequently Assess bowel function Use cautiously with antidepressants and other CNS depressants Naloxone is used to reverse opioid overdose |

Relieves moderate to severe pain | Respiratory depression

Confusion Hypotension Light-headedness Dizziness Sedation Constipation Nausea and vomiting Sweating |

Critical Thinking Activity 10.7a

Oral morphine was administered to a patient for rib pain (rated as “6”) from metastatic lung cancer.

When should the effectiveness of the medication be evaluated?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” sections at the end of the book.

Naloxone (Narcan)

Mechanism of Action: Naloxone reverses analgesia and the CNS and respiratory depression caused by opioid agonists. It competes with opioid receptor sites in the brain and, thereby, prevents binding with receptors or displaces opioids already occupying receptor sites.

Indications: Naloxone is indicated for the complete or partial reversal of opioid depression, including respiratory depression induced by natural and synthetic opioids.

Nursing Considerations: Naloxone is safe for all ages.

Side Effects/Adverse Effects: Adverse effects include tremors, drowsiness, sweating, decreased respirations, hypertension, nausea, and vomiting.

Patient Teaching & Education: Patients should be advised regarding the risks associated with opioid analgesic use and the need for opioid antagonists. Please see the outlined “Special Considerations” for usage below.[14]

Special Considerations

Postoperative: The following adverse events have been associated with the use of naloxone hydrochloride injection in postoperative patients: hypotension, hypertension, ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation, dyspnea, pulmonary edema, and cardiac arrest. Death, coma, and encephalopathy have been reported as results of these events. Excessive doses of naloxone in postoperative patients may result in significant reversal of analgesia and may cause agitation.

Opioid Depression: Abrupt reversal of opioid depression may result in nausea, vomiting, sweating, tachycardia, increased blood pressure, tremulousness, seizures, ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation, pulmonary edema, and cardiac arrest, which may result in death.

Opioid Dependence: Abrupt reversal of opioid effects in persons who are physically dependent on opioids may precipitate an acute withdrawal syndrome, which may include, but not limited to, the following signs and symptoms: body aches, fever, sweating, runny nose, sneezing, piloerection, yawning, weakness, shivering or trembling, nervousness, restlessness or irritability, diarrhea, nausea or vomiting, abdominal cramps, increased blood pressure, and tachycardia. In the neonate, opioid withdrawal may also include convulsions, excessive crying, and hyperactive reflexes.

Now let’s take a closer look at the medication grid on naloxone in Table 10.7b.[15],[16]

Table 10.7b Naloxone Medication Grid

| Class/Subclass | Prototype/Generic | Administration Considerations | Therapeutic Effects | Adverse/Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid Antagonist | naloxone | Given parenterally and inhaled

Assess for reversal of opioid effect Assess for hypertension Assess for return of pain Naloxone has a shorter duration of action than opioids, and repeated doses are usually necessary |

Blocks the effects of opioid CNS and respiratory depression | Agitation

Tremors Drowsiness Sweating Decreased respirations Hypertension Nausea and vomiting |

Critical Thinking Activity 10.7b

A postoperative patient just received naloxone for respiratory depression.

When should the patient’s respiratory status be reassessed?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” sections at the end of the book.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Understanding drug overdoses and deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html ↵

- “3 Waves of the Rise of Opioid Overdose Deaths” by National Vital Statistics System, CDC is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, December 19). Opioid overdose, Understanding the epidemic. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Understanding drug overdoses and deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Clinical practice guidelines for prescribing opioids - United States, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/rr/rr7103a1.htm?s_cid=rr7103a1_w ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Clinical practice guidelines for prescribing opioids - United States, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/rr/rr7103a1.htm?s_cid=rr7103a1_w ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Clinical practice guidelines for prescribing opioids - United States, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/rr/rr7103a1.htm?s_cid=rr7103a1_w ↵

- The Joint Commission, Division of Healthcare Improvement. (2019). Drug diversion and impaired health care workers. Quick Safety (48). https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news-and-multimedia/newsletters/newsletters/quick-safety/quick-safety-48-drug-diversion-and-impaired-health-care-workers/#.ZDh5THbMI2w ↵

- McCuistion, L., Vuljoin-DiMaggio, K., Winton, M., & Yeager, J. (2018). Pharmacology: A patient-centered nursing process approach. pp. 268-270, 324, 332. Elsevier. ↵

- uCentral from Unbound Medicine. https://www.unboundmedicine.com/ucentral ↵

- Frandsen, G., & Pennington, S. (2018). Abrams’ clinical drug: Rationales for nursing practice (11th ed.). pp. 305, 310, 952-953, 959-960. Wolters Kluwer. ↵

- Vallerand, A., & Sanoski, C. A. (2019). Davis’s drug guide for nurses (16th ed.). F. A. Davis Company. ↵

- This work is a derivative of DailyMed by U.S. National Library of Medicine in the Public Domain. ↵

- uCentral from Unbound Medicine. https://www.unboundmedicine.com/ucentral ↵

- Frandsen, G., & Pennington, S. (2018). Abrams’ clinical drug: Rationales for nursing practice (11th ed.). pp. 305, 310, 952-953, 959-960. Wolters Kluwer. ↵

- This work is a derivative of DailyMed by U.S. National Library of Medicine in the Public Domain. ↵

To receive the opioid, the patient pushes a button on the PCA device, which releases a specific dose but also has a lockout mechanism to prevent an overdose.