7 Lesson Plan Design and Sequence

Martina Vasil

Lesson Plan Design and Sequence

In this chapter, we review how to choose objectives and what a basic lesson structure looks like for K–5 general music. Adjusting for different grades is reviewed and advice on planning out lessons are offered. Finally, sequencing in the three most common approaches used in elementary music are discussed: Orff-Keetman, Kodály, and Dalcroze.

How To Choose Objectives

There are two ways to go about choosing objectives for your lessons. You can start with what you want students to learn and find the right repertoire to get you there. Or, sometimes you find a really great piece of music and can determine many learning objectives that can be drawn from that piece. Referring to Chapter 3 can help you plan the first way, and referring to Chapter 6 on repertoire can help you plan the second way. There is no right or wrong way; I tend to do a mix of both, although I admit that I’m often drawn to the piece of music first (usually due to student interest or culture).

When looking at the National Core Arts Standards (see Chapter 3), it is important to really read them carefully to ensure that you plan a lesson that actually reaches the standard.

Basic Structure

When teaching elementary music, there are so many variations to how often you see your students and for how long. Some schools have 25-minute music classes once every six days, and some have 50-minute classes once a week.

No matter what length, a basic structure of a lesson would be:

- Warmup/Hook

- Imitate/New Content

- Explore/Play with Content

- Create/Perform the Content/Extend the Concept

- Analyze/Reflect/Assess

- Cooldown

Adjusting for Different Grades

For older students in grades 4–5, the explore and create may take the entire class period. For younger students in grades K–2, you may find yourself repeating the the Imitate/Explore/Create several times throughout the lesson before cooling down. Younger children have shorter attention spans and will not be able to spend the class period creating like older children can.

For example, it may look like this for older students:

Day 1

- Warmup/Hook

- Imitate/New Content

- Analyze/Reflect/Assess

- Cooldown

Day 2

- Warmup/Hook/Review Last Week’s Progress

- Explore/Play with Content

- Analyze/Reflect/Assess

- Cooldown

Day 3

- Warmup/Hook/Review Last Week’s Progress

- Create/Perform the Content/Extend the Concept

- Analyze/Reflect/Assess

- Cooldown

Lessons Can Take a Day or a Month

Know that sometimes a lesson you create may take up one class period, maybe two, three, or even up to a month! It all depends on the scope of the lesson, how the students are learning, and/or if it’s a collaborative endeavor. For example, when I taught in State College, PA, I did a collaborative, school-wide project with my art teacher on the movement-inspired work of artist Keith Haring. We both saw students twice a week for 40 min and it took us a month to get through the unit. For me, that was six lesson plans, K–5. I did the same lessons for all students, but just adjusted based on age. If you want to read more, you can access my article about it through UK Libraries. Yes, this kind of project took more time, but the impact on students was deep. They were still talking about Haring months later.

Simplify Your Planning

Another important point to remember when planning is that when you get your first job, you can plan 2 lessons per week. One for grades K-2 and one for grades 3–5. You won’t have the mental capacity to plan six lessons per week with all different content, all while trying to make it through your first year teaching. I really wish someone had told me this when I first started teaching. When you are student teaching, this likely won’t work as you tend to pick up one grade per week and you are being heavily mentored by your cooperating teacher. It’s a totally different feeling when you are alone in your new job and don’t have that support, so be kind to yourself and simplify your planning until you get through your first year of teaching.

Sequencing

Good teaching is heavily dependent on good sequencing and this is where common approaches to teaching music become particularly useful. For some people, these approaches become core to their teaching philosophy, so pay attention and see if any of these approaches in particular resonate with you. For me, I was introduced to Orff-Keetman, Kodály, and Dalcroze as a junior music education major. I was immediately drawn to Orff-Keetman after attending a Saturday Orff-Keetman workshop. The opportunities to create and play drew me in and that became the first approach I was certified in and really shaped my work as a young teacher.

Here are some of the basics of each. There are more approaches, but I’m focusing on the four that we have training opportunities here in Lexington.

Orff-Keetman Approach (also called “The Schulwerk“, which means “school work” in German)

The main sequence of the Schulwerk is imitate, explore, create. It’s important to know a bit of the history of how the approach evolved.

A Little History

Carl Orff was a German composer, and in 1924, Dorothee Gunther hired him to be the music instructor for her new school for women that combined dance, gymnastics, and music. The school trained an innovative ensemble of dancers and musicians in new forms of movement and rhythm with extensive use of improvisation. The students were all adults.

This was a time in Europe where there was high interest in developing new kinds of dance and gymnastics. Dancers like Mary Wigman were creating ground-breaking work and inspiring many people, including Orff.

Orff began teaching with just the use of a piano. He was interested in ancient and antique instruments and had friends who gifted him all types of unpitched percussion instruments. Eventually, someone sent him an African xylophone and he also began using recorders at the school (at the time, recorders were rare and no one really knew how to play them). Orff’s student, Gunild Keetman (pronounced KATE-mon), would be the one to figure out how to play the recorder and she taught the recorder lessons and also created the recorder books.

Eventually, Orff asked his friend Karl Maendeler, a builder of harpsichords, to build him more xylophones like the African one he had. He started with an alto xylophone and over time the full pitched set of instruments were built: bass, alto, soprano xylophones; bass, alto, soprano metallophones; alto and soprano glockenspiels; and bass bars.

Orff’s work in his music classes included many of his compositional influences:

- Medieval, Baroque, and Renaissance music

- Dance movement theories of Dalcroze (see later in this chapter for more on Dalcroze)

- Elemental dancing of Mary Wigman

- Sounds for dance, using instruments anyone can play (e.g., unpitched percussion)

- Global connections

- Gamelans & Xylophones

- African drums & rattles

- Chinese and Javanese shadow puppets

You can hear many of these influence in Carmina Burana, which was composed during his work at the Guntherschule, between 1935–36.

Hitler’s government closed the Guntherschule down in 1943 and soon after the school building was bombed during fighting. After World War II, Keetman and Orff redeveloped their work at the Güntherschule for children. They thought that elemental music based in speech, movement, and dance could become basis of early childhood music. Orff and Keetman began to test the new concept in nursery schools and kindergartens. In 1948 they did a radio broadcast series featuring children performing elemental music on a small set of Orff instruments, which widely spread interest in music for children.

From 1950–1954 they published a five-volume series, Music for Children, which was a compilation and reworking of Orff and Keetman’s pre-war work. Today, it’s been translated into 18 languages, with exercises adapted to each country’s rhythms and music.

Central Concepts and Sequencing

Rhythm and speech are the foundation of the Schulwerk and creativity is the main goal. Orff teachers create lessons where students sing, say, play, move, and create.

The main teaching process found in the Schulwerk is imitate-explore-create. Imitate can take many forms, but usually the teacher models and the students imitate. Imitation can be imitating a recording, however, or students imitating a peer, or movement seen on a video. Explore means that the teacher guides students to actively examine and explore a concept, whether that’s through a game, a dance, or playing instruments. Create is giving students the autonomy to create something new, usually using elements of what they explored. This means creating music or movement.

Other common processes found in the Schulwerk that provide excellent scaffolding for learning are:

- Speech to body percussion to instruments. If students can rhythmically chant a word pattern or sentence, then say and tap or map the rhythm/melody somewhere in their body, they will be much more successful transferring the rhythm/melody to an instrument.

- Simple to complex. You will notice that Orff teachers will often talk about “elemental” music. This means that you break musical concepts down to the smallest pieces so that composition flows easily for children. Think of it like building with Legos. You have lots of small, simple pieces that can be combined in endless ways to create a piece.

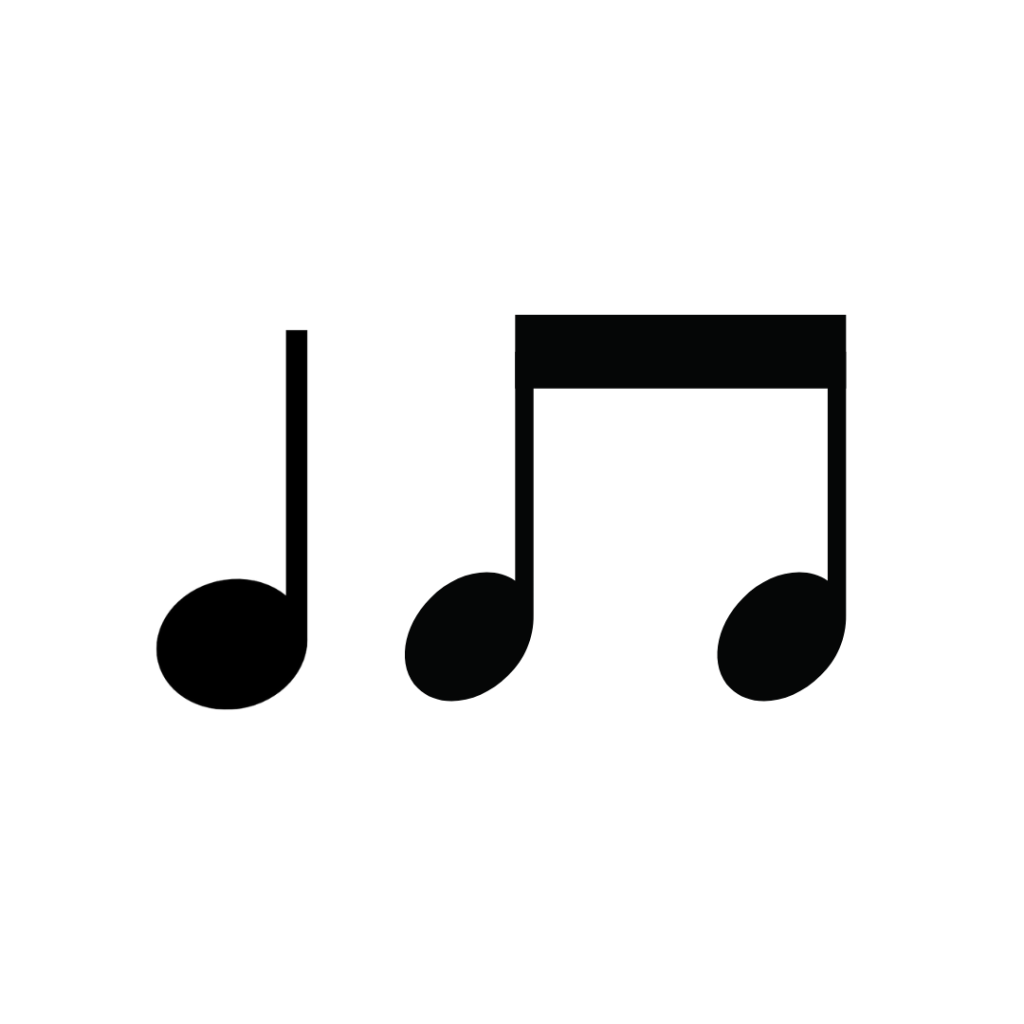

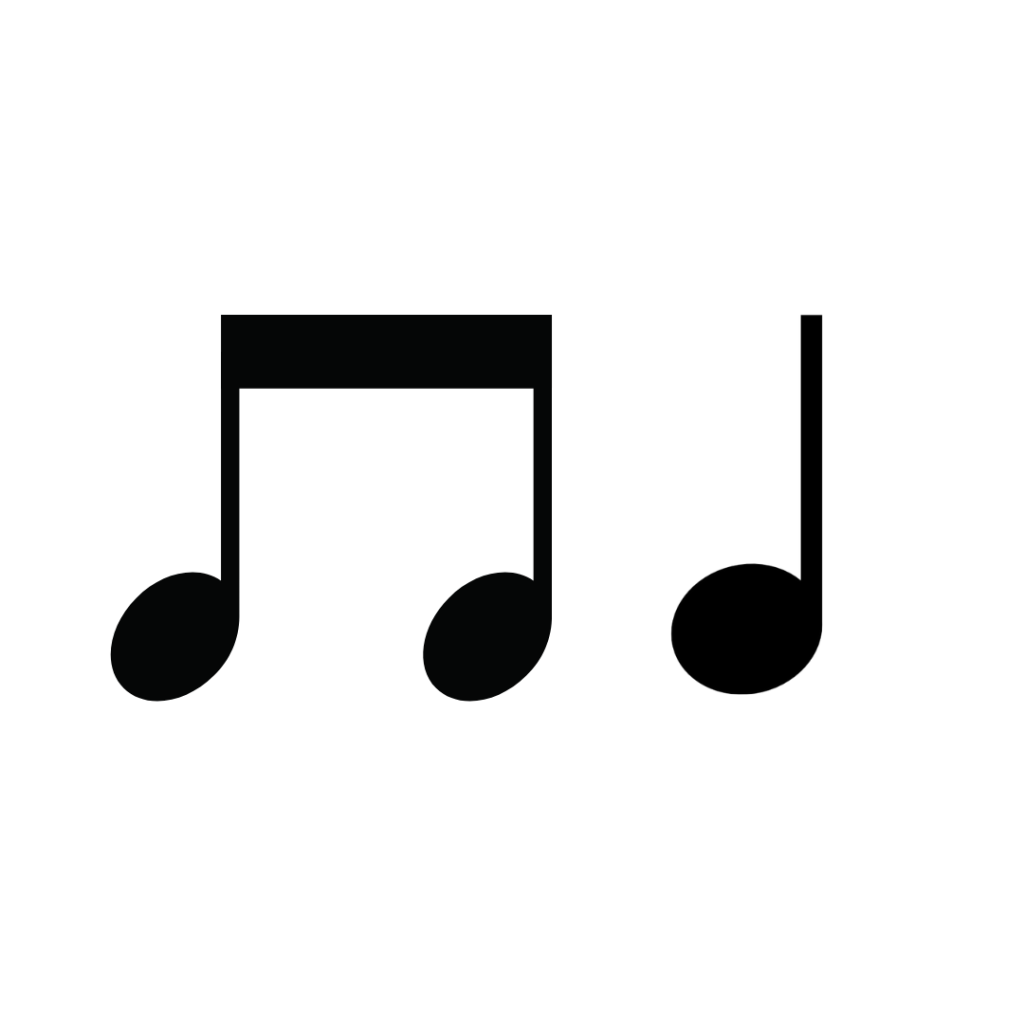

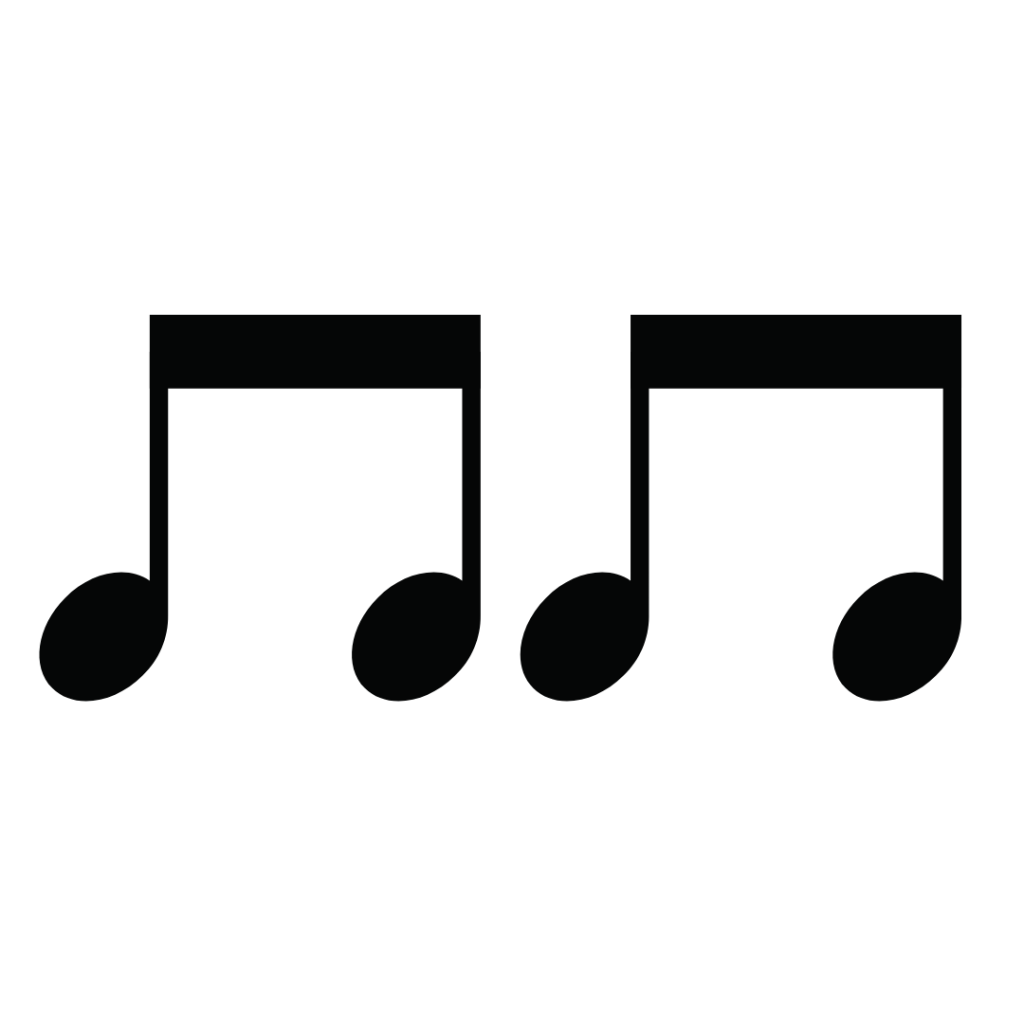

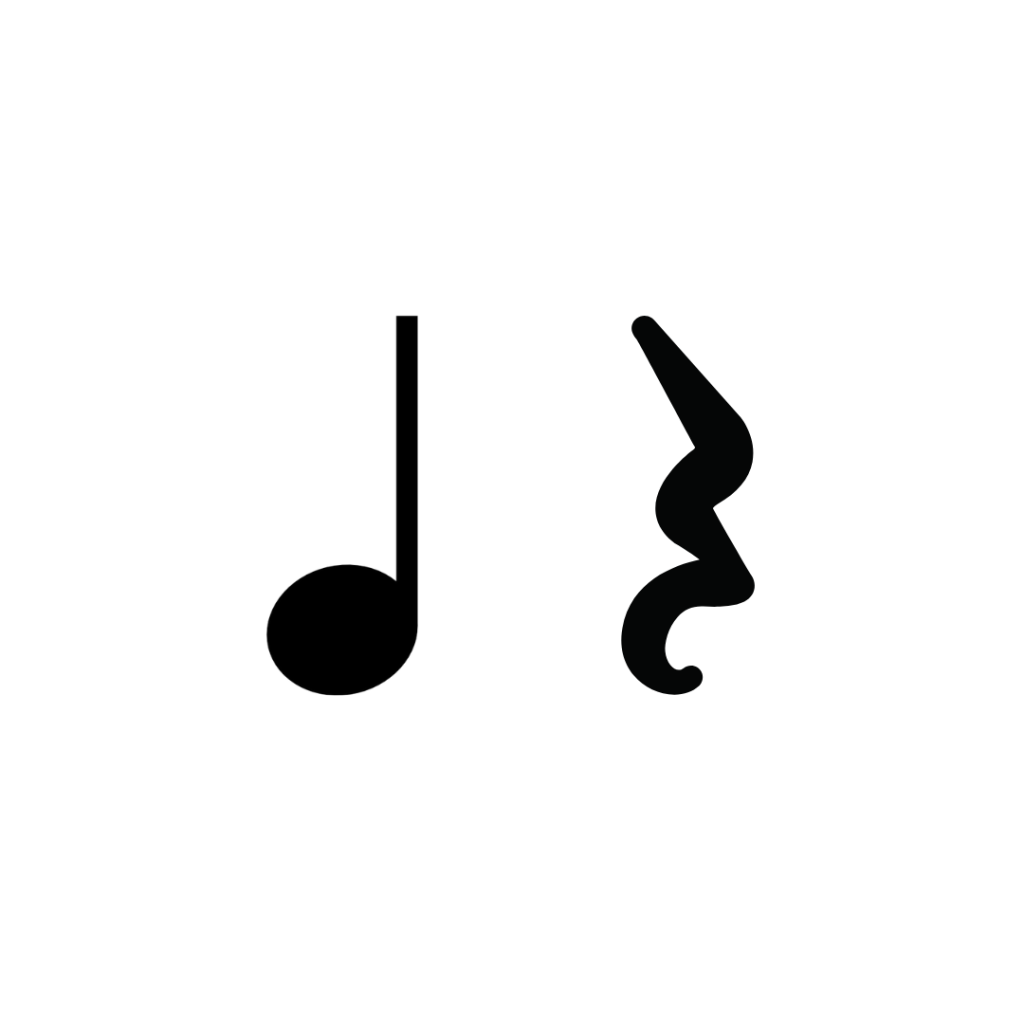

Simple to Complex Rhythms

Orff teachers use rhythm “bricks” to introduce rhythms to children. Here is a set of the most common rhythms, two-beat duple rhythms. Words will be matched to the rhythms to help unit speech and rhythm. For example, one year I did a mountain theme in my classroom. My words were: An-des, Mount Fuji, Cascade Range, Him-a-la-ya, Alps.

When teaching rhythms, I’d begin with students imitating me saying and tapping the rhythms on my body (body percussion).

Imitate: I’d start with each brick individually, then start modeling two brick phrases, then four.

Explore: I’d ask for student input on combinations. “Should we repeat a rhythm?” “Which rhythms sound good at the end, to make it sound final?”

Create: Then I’d have pairs of students work together to create their own four-brick rhythm composition. They need to perform it first, then we work on writing it down.

In another lesson, we might take their compositions and put them on unpitched percussion. Students would be expected to say the words as they play. This could expand to putting the rhythms on barred instruments to make it a melodic composition.

This would be an appropriate activity for 3rd grade.

Kodály

A Little History

Zolton Kodály (pronounced KO-die) was born in Hungary and was surrounded by a rich folk culture in the small village he grew up in. He could sing before he could speak and was very intelligent. His parents were amateur musicians and he got his PhD in composition and linguistics.

Kodály’s ideas were rooted in the historical, social and cultural circumstances of Hungary of early 20th century. German/Austrian musical influences were strong for over two centuries in Hungary and he wanted to elevate and honor the music of his native land.

Central Concepts and Sequencing

Please take note that the Kodály approach is NOT A METHOD. He did not work out the methodology of teaching the music. He had PRINCIPLES that his followers elaborated and developed.

Core concepts of Kodály are:

- Early childhood music education. Music education should start as early as possible.

- Learning should be joyful. Music should be taught in a joyful way.

- Develop aural skills. Aural skill development should be central (versus reading first) and done through part-singing.

- Quality music. Kodály was concerned with using the highest quality repertoire possible. The word “quality” can be of issue however—who determines what is “quality”? At the time, Kodály was referring to the folk songs of different nations and Western art music. We know today that many other genres of music are worthy and should be considered quality. This includes popular music and jazz.

- Active understanding through singing. Just as rhythm and speech are the foundation of the Schulwerk, singing is the foundation for the Kodály approach.

- Global connections. Related to “quality” music, Kodály was fervent about using “music of the people” in the music classroom; this meant folk music from around the world. Today, much popular music has become the music of the people.

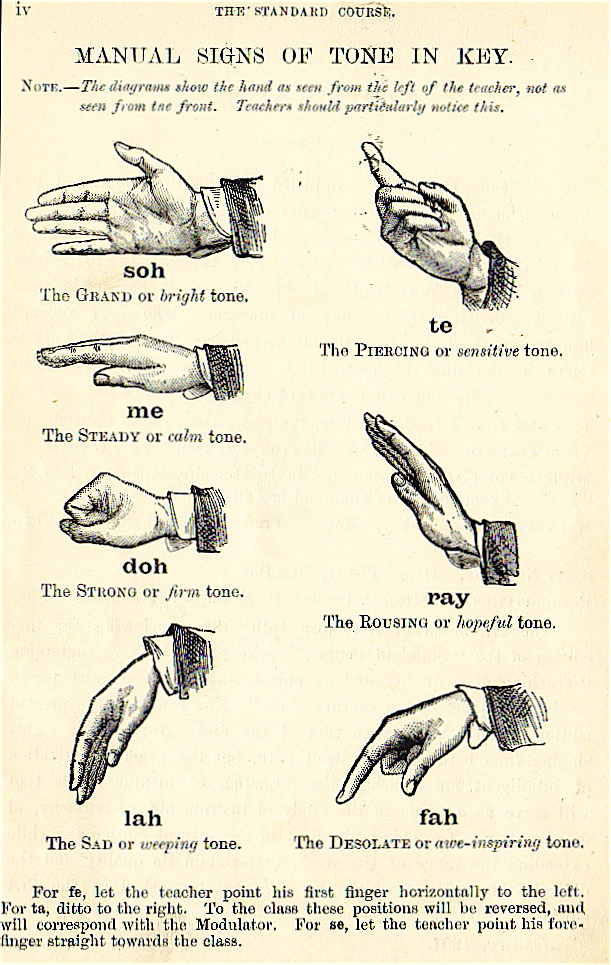

- Music literacy. Learning how to read and write music was important to Kodály. At the time, it was the way to preserve his native Hungarian music. He believed that solfège led to better sight-reading. This is why the Curwen hand signs and solfège are associated with this approach.

- The main sequence of Kodály is prepare, present, practice.

Author, John Curwen (1816-1880). Standard Course, London 1884, page viii (cited from https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.272626/mode/2up)

Dalcroze

A Little History

Émile Jaques-Dalcroze was born in Vienna, Austria in 1865, but grew up in Geneva, Switzerland where he later attended the College and Conservatory of Geneva, graduating in 1883. From there, he went to Paris to pursue a career as a tenor singer, as he was talented in drama and music. He also composed music for a musical theatre and began developing his pedagogy by integrating music and movement in exercises.

When Dalcroze was 21 years old, he returned to Geneva and was hired to be an assistant conductor in a theatre in French Algeria, Africa. The musicians could easily play in changing meters and had an excellent sense of ritardando and accelerando; this greatly impressed Dalcroze. “[Dalcroze] conceived of the Algerians’ performance of rhythm as representative of a deeper human impulse to express the irrational nature of emotion and feeling” (Schnebly-Black & Moore, 2003, p. 6). He thought that this kind of rhythmic talent could be cultivated in western Europeans if they started early enough and could eventually help western Europeans get in touch with their spirituality and emotions.

A year later, Dalcroze returned to Vienna to study with Adolf Prosnitz. Dalcroze developed the belief that improvisation should be central to music education because it helped validate students’ thoughts and feelings; the students learned to teach themselves and the teacher acted as a guide.

In 1892, at 27 years old, Dalcroze became Professor of Theory and Solfège at Geneva Conservatory. His students did not move musically and were not hearing the changes in the music well, and so he began implementing his music and movement ideas in order to improve their musicality.

After speaking with Geneva child psychologist Eduoard Claparede, he tried new approaches to speed up his students’ kinesthetic response time. Dalcroze started with direct commands (e.g., “hop”) and over time made his commands more and more nuanced (i.e., a change in tempo or articulation elicits a response rather than a direct command—“hop!”). Both Dalcroze and his students engaged in the process of stimulation-response-observation-revision. As students became more sensitive to the changes Dalcroze performed on the piano, he became more sensitive to students’ movements. The students became the teacher, in a sense (Schnebly-Black & Moore, 2003).

Dalcroze also noticed that his students lacked vitality when responding to music. He realized that walking would be the best way for his students to respond. Walking forces students to balance; they have to maintain a certain tempo when walking, a tempo that remains fairly even or they will lose balance; and walking has energy as each leg thrusts the body forwards.

By 1903 he was introducing physical movement to accompany sight-singing in his classes. With walking established, Dalcroze wanted students to show the beat through a variety of gestures (conducting clapping, swaying, twisting, etc). Different body parts required different kinds of energy to move to the beat, each with a different tempo, articulation, and direction. Once students mastered control over large muscle groups, they had improved control over smaller muscle groups. Over time, students expanded their capacity for expression and balance.

Central Concepts and Sequencing

In Dalcroze eurhythmics, there is always a balance of time, space, and energy. Music shares characteristics with how our bodies interact in the word. Music can rise/fall, pause/hurry, and push/pull. There is a sense of weight as our bodies move through time and space, and the way we move determines the amount of energy we give (Schnebly-Black & Moore, 2003).

Eurhythmics in particular develops muscle memory for time, space, and energy to improve musicianship (Meade, 1994; Schnebly-Black & Moore, 2003). “Eurhythmics trains the whole body to respond to music, words, and even visual impressions” (Schnebly-Black & Moore, 2003, p. 35). Generally, movement begins with the whole body, to isolated parts, to harmonizing and opposing with others, and finally, finding balance (physically, emotionally, and spiritually) (Schnebly-Black & Moore, 2003).

There are four branches to the Dalcroze approach: eurhythmics, solfège, improvisation, and plastique animée. Together, Dalcroze believed that his approach could help create a solid rhythmic foundation for musicianship, improve audiation and listening skills, and help reconnect people’s bodies with their minds. He believed in the embodiment of music and through his approach, sought to help students innately learn concepts that they could identify later. The Dalcroze approach is a slow learning process, but worth the time for the resulting depth of understanding.

Eurhythmics is based on improvisation and personal expression. The lesson is dependent on the individual teacher’s creativity and relies heavily on contrasts: in rhythm and meter, sound and silence, tempi, style, and oppositions in gestures. Generally, movement begins with the whole body, to isolated parts, to harmonizing and opposing with others, and finally, finding balance (physically, emotionally, and spiritually). The purpose of eurhythmics is to train the body to develop muscle memory for time, space, and energy to improve musicianship. Music shares characteristics with how human bodies interact in the world. Music can rise/fall, pause/hurry, and push/pull. There is a sense of weight as bodies move through time and space, and the way one move determines the amount of energy one gives. Watch a video of eurhythmics with children here.

Solfège is used to develop audiation and a keener sense of hearing. Fixed do solfège is used in the Dalcroze approach for historic reasons; it was the main method of teaching solfège in Dalcroze’s time. Fixed do is a solfège system that assigns a specific pitch to each syllable, regardless of the key or tonality Fixed do is particularly useful for helping the student hear tonal relationships. Activities for solfège include singing scales from low do (c) to high do’ (c’). This requires students to audiate the tonality before singing the scale—they have to be able to recontextualize do into various places in scales. See how solfège is used in this video.

Improvisation typically occurs at the piano; basic piano technique and knowledge of solfège is used to create musical improvisations, which is used heavily in teaching eurhythmics. This may begin with improvising simple melodies, adding simple ostinato patterns to accompany the melody, and then adding nonfunctional harmony and functional harmony. See examples of Dalcroze piano improvisation here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OEdafRQ9yD8

Plastique animée is the expression of music in movement, embodying all aspects of the music and making it visible. Unlike choreography, plastique animée offers freedom of expression that goes beyond learned series of movements or fixed aesthetic objectives. The goals of plastique animée are for students to discover, understand, and reveal the musical text; bring all musical elements learned together in a structured way and in a group; to have natural expression; to connect movements to personal experiences and feelings; and to achieve perfect balance in bodily motions, that is, being able to control bodily movement in relation to time, space, and energy. See an example here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AP4v0UeZ418

References

Anderson, W. T. (2011). The Dalcroze approach to music education: Theory and application. General Music Today, 26(1), 27–33. doi:10.1177/1048371311428979

Gray, E. (n.d.). Orff Schulwerk: Where did it come from? Echoes from the Past. aosa.org. https://aosa.org/experts-blog/echoes-from-the-past/

Juntunen, M. (2012). The Dalcroze approach: Experiencing and knowing music through embodied exploration. In S. Burton (Ed.), Engaging musical practices: A sourcebook for middle school general music (pp. 141–166). Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Meade, V. (1994). Dalcroze eurhythmics in today’s music classroom. Schott Music Corporation.

Schnebly-Black, J., & Moore, S. F. (2003). The rhythm inside: Connecting body, mind, and spirit through music. Alfred Publishing Co.