8 Assessment

Martina Vasil; Judi Reynolds; and Chris McDowell

Music assessment at the elementary level can seem quite daunting because of the number of students involved and the limited contact time. However, it does not have to be complicated! Assessment should be an integral part of your daily teaching; think of assessment as a source of information for both you and your students. Frame your assessment as “checking” versus “grading.” As Burnett said (2012, para 1):

- Checking is Diagnostic. Teacher as advocate.

VERSUS

- Grading is Evaluative. Teacher as judge.

Think of assessment as formative or summative and informal or formal.

Formative Assessment

Formative assessment is what it sounds like…it’s formative. This is the kind of daily assessment you do in the classroom as you are teaching music. Are most students singing in tune? Are they getting the rhythm right? What do I need to do to help them achieve musically? This kind of assessment is usually informal (you look and assess), but it can also be more formal.

Summative Assessment

Summative assessments in music usually looks like a final performance or composition in class, a final project, or final performance (concert). The important thing to remember is that a lot of formative assessment should be occurring before a summative assessment is used.

Informal Assessment

Informal assessment is what teachers do every single day in the classroom. They observe and assess where students are, making thousands of micro-decisions daily. Informal assessment doesn’t get written down and there’s no physical evidence of the assessment.

Formal Assessment

Formal assessment is what it sounds like, it’s more formal. Data is captured in some concrete way to do an official analysis. This can mean video taping your students, audio recording, using a rubric, or using a form to track student success over time.

School Requirements

Some schools require formal assessments and grades, but many others do not. For example, Mr. McDowell’s school does not require the special area teachers to give grades. They typically see each student once a week during a 50-minute class. Sometimes they do not see students for several weeks or months because of band, orchestra, sickness, etc. Mr. McDowell only uses informal and summative assessments in his classroom because of the lack of time with each student. Also, his special area team has chosen not to give formal assessments in their classes because the students receive constant formal assessments in their homeroom class. They have also noticed many students have developed a fear of making mistakes, but they welcome mistakes especially when these mistakes are accompanied with student effort.

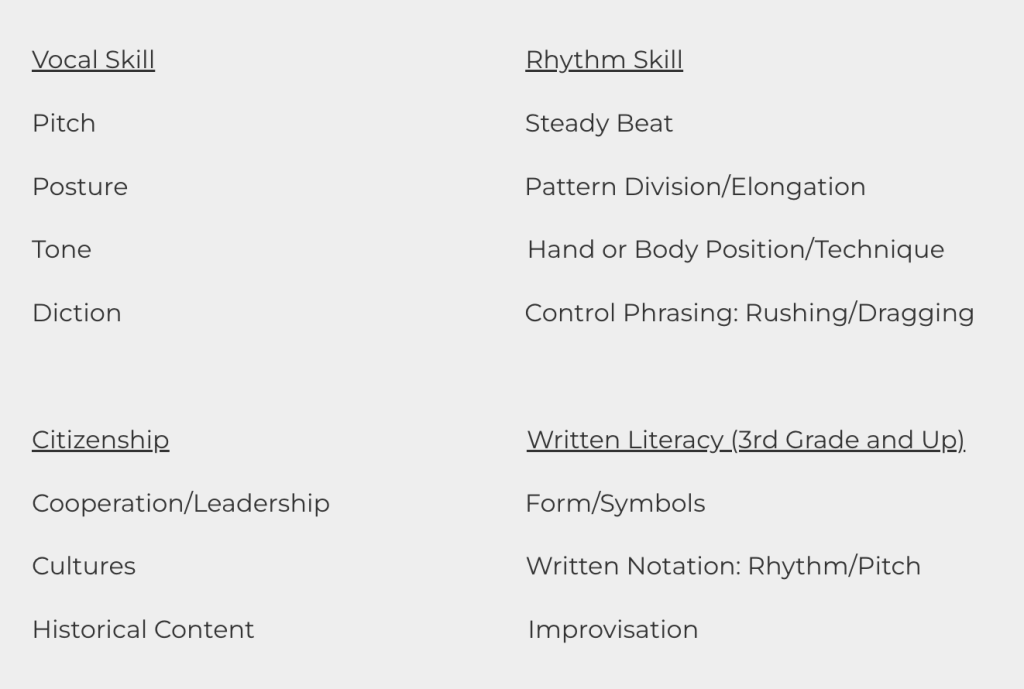

Music Skill Criteria

Common skills to assess are listed below. These are the criteria Brian Burnett developed to use in his elementary school in Toledo, OH.

Assessment Tools

This section examines specific assessments you can use in the classroom. Keep in mind that these can be use for both formative and summative assessment; it just depends on how you use them.

Singing and Beat-Keeping Games

For example, let’s say you want to track your students’ ability to match pitch and perform a steady beat. Singing games are a low-stakes, low-stress way for you to hear individual students and assess their ability to match pitch and to reinforce steady beat. This is something that happens very organically in a lesson and does not take a lot of time. Watch this 11-min video to see how Lynn Kleiner embeds a pitch matching and beat assessment with five-year-olds (Kindergarten). She provides a starting pitch and sometimes has to support the singing by modeling and singing along. Sometimes she has to verbally remind students to match the steady beat and sometimes uses a verbal cue. Keep in mind that she would have gone over how to play the instruments in another lesson (never assume the children will just know). Also notice how much BETTER the children kept the beat once she had them sing (near the end of the clip). That’s what the passing game prepared them for (refer back to Chapter 7 where you see the Orff process of speech to body percussion to instruments).

Check out another example of singing assessment in this 3-min video here. In this case, the class learned the whole song with gestures. At the time the video was taken, it was near the end of class and children had the chance to sing the whole verse, or split the verse among four students:

Chicken and a chicken and a crowd of crows

I went to the well to wash my clothes.

When I got there my chicken was gone,

What time was it old witch?

It was ____ o’ clock. ____ o’ clock [everyone sings]

This song is from Down in the Valley by the New England Dancing Masters.

Folk Dances and Dalcroze Activities

Folk dances are an excellent way to assess movement, rhythm, and even melodic understanding. The following example is from Burnett (2012) and the dance is “Highway No. 1” from Shenanigans – Folk Dances of Terra Australis, Vol. 3.

Watch the video of the folk dance here. This is an excellent folk dance for PreK–2 to evaluate movement vocabulary, phrasing, steady beat, rhythmic movement, and movement creativity.

Process

- Prep the students for the movement before hand. This means you’ll need to have the list of movement from the folk dance written down for yourself and you should be ready to model it and have student imitate you.

- After you’ve prepped the students, you can play the audio (don’t show the video yet, you want their ears focused before their eyes) and do the movement with the audio.

- This activity can be played as a “doubling” game. The teacher leads the activity and chooses one child to perform the first movement. On each repetition, the number of students doing the movement doubles.

- When you purchase the Shenanigan’s CD, a blank track is also included which allows for students to add their own movement patterns.

- Later, show the video linked above, as it’s a great way to show Australia and you can lead a conversation about highways in the US and Australia! Maybe even play the song Route 66 (Connecting standard of the National Core Arts Standards).

Dalcroze activities, such as a follow or quick reaction, are useful in to monitoring student understanding. These activities allow the teacher to administer a whole class; it’s an informal performance assessment that can be done quickly without the students knowing they are being evaluated.

Improvisation and Composition

Student improvisation and composition are great for summative evaluations. Many teacher do projects with upper elementary (e.g., fifth grade) that can take several weeks to teach. Projects usually begin with a song or piece of music that serves as the project’s foundation. The students learn, evaluate, and deconstruct this song. The teacher guides them to find patterns and/or specific elements that students identify. Students then use these new discoveries to make their own creations, usually in a small group. These creations are constantly evaluated by the teacher, the individual groups, and the whole class. Once the students have practiced and feel comfortable to perform, the students create a musical form using the beginning song, the student creations, and any other musical element that may have been discovered in the lesson.

Peer Teaching and Peer Feedback

Whole Brain, APL, Kagan, and TAG strategies are useful for peer assessments. Whole brain uses teacher reviews, where you introduce information and give a signal, “teach”. At the signal, predetermined partners “teach” the information to each other given a short timed session.

APL and Kagan both have strategies that involve partner “teaching” to assure mastery. This works and cuts down on the students who may tend to not focus. When you use these, take care to walk around and monitor the groups. Often, one group will “share out” their understanding of the material. These are peer assessments that create an atmosphere of learning and eliminates students who “check-out”. Everyone is accountable to someone.

Kagan has many different strategies that keep things from getting stale. These are formative, peer assessments that work well when one considers the number of students who roll through the music room. A vital element is teacher monitoring to assure compliance.

Ms. Reynolds’s favorite Kagan strategy is “Quiz, Quiz, trade”. She has cards for different assessments. For instance, rhythms will be on the trade cards. Partners “hand-up, pair up” within a short set time. Each partner has a card with a rhythm. One partner shows his rhythm card while the other partner claps or says it. They switch jobs and then trade cards. This process repeats several times—all to a timer to keep it moving. The kids love it. They are “assessing and teaching” each other. She usually does this about five times in a class session so they have five different partners.

Other Kagan strategies that work great include Rally Robin (two students) or Round Robin (four students). Students have a partner and go back and forth over content. For instance, they can say their solfege syllables and hand signs back and forth (again, to a timer).

For a summative assessment, at the end of a unit, you can have a short written assessment. A summative assessment that Ms. Reynolds has found to be quick and successful is one for chords with note cards. She will have one note card with the chords that have been learned in the unit written. Students have a paper clip that they can move to show the chord that is presented on the board. It is a quick and non-writing chord assessment. She reserves these individual assessments for the summative. Of course, if the students can bring Chrome books to class, there are many nice strategies to use.

Using the Kagan hand-up, pair-up also works great in ensembles. Ms. Reynods uses this in rehearsals when students struggling with lyrics. She has students do “hand-up, pair-up” and sing the phrase together. She rotate students through several partners and the students learn the lyrics by being accountable to each other. This strategy really cuts down on “faking-it.”

TAG is something Mr. McDowell came up with for guiding peer feedback. He made posters that he hangs at child eye-level. TAG stands for T (Tell Something You Like); A (Ask a Question); and G (Give a Suggestion). He provide sentence stems to help children gain the language for providing constructive feedback.

T (Tell Something You Like)

- I like the part…because…

- I’m really impressed by…because

- I could really connect with…

- The strongest part of your work was…

- I thought you did…really well because…

A (Ask a Question)

- What do you mean by…?

- Why did you…?

- Could you tell me more about…?

- How did you…?

- Where is…?

- Did you consider…?

G (Give a Suggestion)

- I think your next steps could be…

- I wonder what would happen if…?

- Would it be clearer if you…?

- I think you should add…because…

- One suggestions would be…

- If you…it might…

Rubrics

Rubrics are very useful for both teacher and students. For students, it clearly shows the criteria for helping them judge their own work. It also reduces teacher time for assessment. Rubrics are easy to score and can help you report numeric assessment values to your administration if that’s what they prefer.

Burnett (2012) references Goodrich (1996) when providing suggestions for making a rubric. First, list the criteria for a piece of work, or list “what counts.” Then, establish the graduations from “Excellent” to “Poor” (or use some other terminology) with between 4–6 items of quality. For example:

4 Yes

3 Yes, but

2 No, but

1 No

This 1–4 rating is also very helpful to use in the classroom in the moment. Students can hold their fingers against their chest to rate how they think they did, and the teacher can quickly scan and see at a glance how well students are understanding content. The fingers are held against the chest to keep the rating more private (versus students holding their hands in the air for all to see how they rated themselves; this might also sway student rating of themselves if they can see how their peers rated themselves. We want to avoid that).

You can track the data using a clipboard or your iPad with an Excel sheet pulled up. Have a combined seating chart/grade book for assessments. It’s important to eventually get the data to an online system so you can calculate student or class averages or even create graphics to show the data in different ways.

Vocal Skill Rubric (Burnett, 2012)

Use rubric to evaluate solo/unison singing, canon singing, partner songs, and part-singing

4 (Yes!) Matches pitch consistently with good posture, clear tone, and diction.

3 (Yes, but) Matches pitch, but is not consistent, or one or more of the criteria is missing.

2 (No, but) Pitch is not certain, but posture, tone, and diction may be good.

1 (No) The student is still working to find the singing voice.

Rhythm Skill Rubric (Burnett, 2012)

Use rubric to evaluate performing body percussion, on rhythm instruments, and onmelodic instruments

4 (Yes!) Consistently demonstrates control of the steady beat and complementary patterns with good tone and proper posture or technique.

3 (Yes, but) Shows the steady beat, but is not consistent, or one or more of the criteria is missing.

2 (No, but) Lacks control of the steady beat, but tone and posture may be good.

1 (No) The student is still working to find the steady beat.

Citizenship Rubric (Burnett, 2012)

Use rubric to evaluate performing body percussion, on rhythm instruments, and onmelodic instruments

4 (Yes!) Consistently shows leadership working with others.

3 (Yes, but) Works well with others in teamwork and is a good listener.

2 (No, but) Follows directions and classroom rules, but needs to improve cooperation with others.

1 (No) Needs to follow directions and cooperate with others in class.

Literacy Rubric (adapted from Burnett, 2012)

Use rubric to evaluate improvisation either with a melodic set, a rhythmic set, or movement elements.

4 (Yes!) The improvisation is repeatable, sing-able (by yourself and others). Not composition, but awareness.

3 (Yes, but) The improvisation includes cadences. In melodic improvisation, the cadence sets the tonality.

2 (No, but) The improvisation includes appropriate elements of the tonal or rhythm set or movement elements.

1 (No) The improvisation follows the form or rhythmic structure.

For examples of improvisations, see:

- Melodic/Movement improvisation to a set rhythm (Music for Children,Vol. I, pp. 60-61)

- Melodic/Rhythmic/Movement improvisation to a set phrase structure:

- Question/Answer, Call and Response (Music for Children,Vol. I, pp. 64-66, 79-81)

- Melodic/Rhythmic/Movement improvisation to an elemental form:

- abab aaba aaab abba abac (Elemental folk music and dance)

Pre-Made Assessments

These resources are recommended for elementary music teachers looking for pre-made assessments:

- MusicplayOnline has a menu option of types of assessments. Games and interactive activities are embedded in the curriculum so you can choose to do assessments at any time. This short video shows you have to find the assessments if your school has the Musicplay curriculum.

- QuaverEd has assessments that are more appropriate for grades 3–5. This video gives you a peek into those assessments.

References

Burnett, B. (2012, September 8). Assessment for learning [workshop]. Kentucky Orff-Schulwerk Association.

Davis, A., Amidon, P., & Amidon, M. A. (Eds.). (2000). Down in the valley: More great singing games for children. New England Dancing Masters Productions.

Goodrich, H. (1996). Understanding rubrics. Educational Leadership, 54(4), 14–17.

Griffin, A., Redler, B., & Reed, L. (2024). A sampling of beginning of-the-year assessments. Teaching Music, 32(1), p. 36.