6 Choosing Relevant and Authentic Repertoire

Martina Vasil

There are many factors to consider when choosing repertoire for your classroom. It is important to pick music that is relevant to your student population and that also comes from sources that can be trusted so you know the materials are authentic. Many songs can teach the skills and knowledge you want your students to learn, so please do not feel that once you choose a song, you are locked into it. There will always be another piece of music that can help your students achieve the learning objectives.

Age-Appropriate

I see new teachers struggle the most in choosing repertoire that will be age-appropriate for students. You should consider the lyrics of the song, the vocal range, the musical elements, and the sort of dance/play/movement that is associated with the piece. Try the exercise below and see how you do!

Determining Age-Appropriateness

Watch this video of the Tree Song and this video of At the Bottom of the Sea from the New England Dancing Master’s book, Down in the Valley. What age group might these songs be best for? Why?

Now watch this video of Green Sally Up and this video of Four White Horses from the New England Dancing Master’s book Down in the Valley. What age group might these songs be best for? Why?

*Hint: Look at Chapter 3: What Should Children Know?

Clearly (or maybe not so clearly since you are new to this), the first two are best for younger children in grades PreK–2. The Tree Song is an action song, where the movement follows the words in very simple, concrete ways that young children can follow. What is tricky with At the Bottom of the Sea is that it has a large vocal range that would be appropriate for older students. However, the game is “follow-the-leader” and encourages dramatic play, which is age-appropriate for PreK–2. While the teacher would sing the whole song, young children would only sing on the “ohhhh, [name, name] we love you,” which is a smaller singing range appropriate for young children.

The last two examples are for older children. The complex hand-clapping patterns give an appropriate challenge for older students, and both songs have interesting/funny phrases that would attract older students’ interest and attention, much like riddles and jokes. For example, in Green Sally Up, there is the phrase, “he jumped so high, he touched the sky, and he didn’t come back ’til the Fourth of July.” In Four White Horses, there is the phrase “shadow play is a ripe banana.” Both songs also have a lot of syncopation in the melody and Green Sally Up has a minor melodic pattern (mi re do la), which is interesting and an appropriate challenge for older students to identify and sing. That is not to say you can’t sing syncopated or songs in minor tonality with younger students…the learning objectives would be different. This brings me to the next section, choosing repertoire according to what skills you want students to learn/practice.

Skill-Appropriate

The four pieces of repertoire you watched are good examples of being skill-appropriate for certain age groups. Looking back at Chapter 3, you learned approximately what students “should” know per grade level. For younger students, you can play with tempo (fast/slow) and dynamics (loud/quiet) with The Tree Song and At the Bottom of the Sea, even though those concepts are not directly built into those songs. Both songs encourage whole body movement and dramatic play, which is important for young students in building their body awareness. At the Bottom of the Sea encourages social interaction and reinforces the concept that all students are loved”, an important social-emotional goal. Both songs can be used to reinforce steady beat, especially at the Bottom of the Sea if you want students swimming to the beat as they play “follow-the-leader” around the room.

For older students, more complicated solfège patterns can be found in both songs. Four White Horses has a “ti re do” (rainy day, shadow play) and Green Sally Up is in minor and the pattern “mi re do la” is appropriate to isolate and identify for older children (e.g., on the words: possum brown, jump the fence, fourth of July).

Beyond thinking about age-appropriateness and what musical skills could be focused on in song, it is important to think about why a song was written and if the historical context of a song or piece of music could be problematic or hurtful to your students.

Racist Folk Songs

*Trigger warning: this next section will briefly discuss blackface, minstrel shows, and other depictions of racism. Information is from the National Museum of African American History and Culture: https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/blackface-birth-american-stereotype

In the past ten years, there has been increased conversation surrounding the racist history of many folk songs, which were originally created to be minstrel songs. Over time, the lyrics have been changed and made their way into our music education repertoire.

You may be asking yourself, what is a minstrel song/show? It is a performance where white performers painted their faces black (i.e., “blackface”) and acted in an exaggerated way of how they perceived black people. Blackface began as early as the 1830s, when white performers would darken their faces with burnt cork or shoe polish, wear tattered clothes, and mimic how they viewed enslaved Africans on Southern plantations. They characterized black people as lazy, ignorant, superstitious, hypersexual, and prone to thievery and cowardice. These performances were called minstrel shows and lasted well into the 1900s. Even today, we still find instances of blackface in Halloween costumes at colleges and universities across the US, as this 2018 article from Inside Higher Ed reveals.

Many minstrel songs originally used the n-word and over time, lyrics were replaced or disappeared. It only takes a quick Internet search to find the original. Other folks songs portray racist caricatures of black people, such as the “mammy” character so often see in early US films, such as Gone with the Wind. Even food products have used this harmful image (Aunt Jemima’s and Mrs. Buttersworth pancake syrup. Read more here).

Other songs provide an inaccurate and stereotyped version of what indigenous North American music sounds like (i.e., Land of the Silver Birth and The Canoe Song). See here for an extensive discussion of this topic from, Michelle McCauley, a Native American music educator.

A Sampling of Folk Songs

Dr. Ian Cicco’s dissertation examined the history of many folk songs. Songs he recommends you do not use are marked with an “x”. An explanation of why is in parentheses. These are listed in alphabetical order.

| A-Tisket, A-Tasket | |

| Angel Band | |

| Barbara Allen (adult themes) | x |

| Black Jack Davey (violent history) | x |

| Chicken on a Fencepost (n word) | x |

| Coming ‘Round the Mountain | |

| Cotton Eye Joe (tied to blackface) | x |

| Cripple Creek | |

| Cumberland Gap | |

| Dinah (mammy caricature) | x |

| Eeny Meeny Miney Mo (n-word) | x |

| Go Tell Aunt Rhody | |

| Great Big House (other verses refer to slavery, i.e., whipping and masters) | x |

| I’ve Been Working on the Railroad (n-word) | x |

| Jim Along, Josie (n-word) | x |

| Jimmy Crack Corn (Blue Tail Fly) (n-word) | x |

| Johnny on the Woodpile (n-word) | x |

| Johnson Boys | |

| Land of the Silver Birch (stereotyping indigenous music, inauthentic) | x |

| Liza Jane (ties to minstrel shows) | x |

| Love Somebody | |

| My Paddle (Canoe Song) (stereotyping indigenous music, inauthentic) | x |

| Oh, Fly Around My Pretty Little Miss | |

| Old Dan Tucker (minstrel) | x |

| Old Joe Clark | |

| On Top of Old Smokey | |

| Pick a Bale of Cotton (depicts slaves picking cotton) | x |

| Pretty Polly | |

| Shady Grove (sexual references) | x |

| Shorten-in (Shortnin’) Bread (n-word in some versions, mammy caricature) | x |

| Skip to My Lou (n-word) | x |

| Sourwood Mountain | |

| The Cuckoo | |

| The Mockingbird | |

| The Ship That Never Returned | |

| Tom Dooley (violent) | x |

| Turkey in the Straw (n word, minstrel) | x |

| Turn Your Glasses Over (had n-word) | x |

| When the Saints Go Marching In | |

| Wondrous Love |

Songs with a Questionable Past

Bookmark this webpage here for a continuously updated list of “Songs with a Questionable Past.”

Folk Songs

Folk music is “the music of the people” and thus it will be the most common type of repertoire you come across. Folk songs tend to evolve slightly over time, particularly with lyrics, but the main structure and melody/rhythm stay the same.

Resource books and websites should be clear about the origin and purpose of these songs so you can feel confident in knowing the background. Children’s playground chants, games, and songs have staying power, as do many nursery rhymes and other traditional types of music.

I argue that the new folk music of the world is popular music, since in the past 100 years, that has become the music of the people. My conviction of this was even more deeply confirmed after working with refugee and immigrant children from Ghana and the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2020. When I asked them the music they knew best and wanted to learn, it was not the traditional music of where they were born…it was popular music! I explain why popular music should be a central part of the repertoire you use in general music below.

Popular Music

There has always been popular music throughout time, but in the US, one might consider the roots of our current popular music as existing for about 100 years now (if you start in the 1920s with the rise of the popular music industry in Tin Pan Alley). One might say that popular music has become the new folk music of our time, with certain songs sustaining popularity (i.e., Queen’s “Another One Bites the Dust”, Michael Jackson’s “I Want You Back”). It is important to view popular music as a legitimate form of repertoire that is just as authentic and “quality” as music our profession typically puts on a pedestal (i.e., Western classical music).

When including popular music, however, you need to be mindful of the authentic ways popular musicians learn and perform music—informally (Green, 2002).

- Learning in a friendship group

- Choosing the music themselves (not by an adult or outside institution or body)

- Learning music by ear

- Co-constructing musical content

- Spending lots of time engaged in self- and peer-study

Picking a band or choral score of a popular song and reading it through is not a legitimate or authentic way to teach popular music. Popular music should be taught by ear and allow time for student to work on their own or with peer partners/groups. The teachers is a facilitator rather than director. Students should have a say in what they play and should be encouraged to make changes to a song to make it their own. They should eventually move to writing their own songs. You will learn more about this in MUS 361 Modern Band next semester.

Multicultural Music

Using multicultural music in the classroom stems from the ideals of freedom, justice, equality, equity, and human dignity as acknowledged in the U.S. Declaration of Independence and the U.N. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The purpose is to prepare students for life in an interdependent world of diversity by race, ethnicity, class, sexuality and affirm cultural differences and the pluralism of people and their communities.

To teach multicultural music, many teachers use world music pedagogy (WMP), an approach focused on:

- how the music is taught and learned within a culture

- how best the music processes can be preserved or adapted for classroom use

There is a five-step model of world music pedagogy:

- Attentive Listening. Stimulate student critical listening with specific questions; “What do you hear?” “Voices? Instruments?” “Are there any repeated phrases?”

- Enactive Listening. Invite students to listen while doing. For example, “Pat the repeating rhythmic pattern you hear in the song as we play it again.”

- Engaged Listening. Invite students to do without listening (without the recording). For example, sing a recurring pattern, practice an instrumental part, or perform several parts together vocally or on instruments.

- Creating World Music. Show students how to take the principles of a piece or style of music and apply it to a new piece of music. For example, after learning a song in call-response form, work in small group to write in the same form, or after learning a song in call-response form, work in small groups to write in the same form.

- Integrating World Music. Connect to the cultural context of the song throughout a lesson. There will be many opportunites to discuss the purpose of the music, when and why it would be played, what the musicians would wear and why, any many other connections to the country and culture the music is from.

Other Genres

Include anything else that you want! Classical, Jazz, New Age, etc.

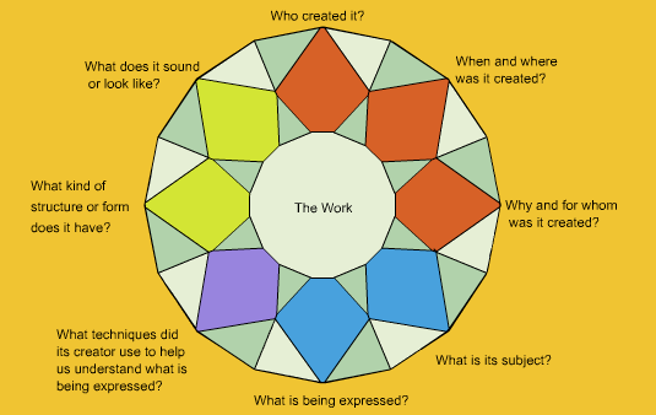

Facets Model

If you are unsure of the authenticity of a piece, the Facets Model can be useful in analyzing the music. The Facets Model was created to promote the comprehensive study of a musical work and enhancement of students’ musical understanding and performance (Barrett et al., 1997). The goal is to have students understand the context of a piece, and in turn have a deeper and more meaningful experience with the piece. Using this model, students and teachers can uncover the answers to a series of questions that will lead to cross-curricular connections and critical thinking skills.

Ask the following questions:

- who created it,

- when and where was it created,

- why and for whom was it created,

- what does it sound or look like,

- what kind of structure or form does it have,

- what is its subject,

- what is being expressed, and

- what techniques did its creator use to help us understand what is being expressed (Barrett et al., 1997, p. 252)?

Additional questions that can be asked are:

- how and to whom is it transmitted,

- who performs, dances, listens to, and values it,

- what does it mean within historical/cultural contexts,

- what is its function for individuals and groups,

- what does it mean to individuals and groups,

- how do differences in performance or interpretation change its meaning, and

- how does it change through different interpretations or versions?

Other Tips from Mr. McDowell

Most of the music Mr. McDowell chooses is connected to his curriculum and serves as a way for the students to experience a musical element, identify a musical element, or understand the function of a musical element. If he cannot find music that fits his needs, he creates the music himself or he alters a piece of music.

Examples of Mr. McDowell Creating Music for His Curriculum

Example 1: Mr. McDowell’s first grade concert focuses on Do, Re, and Mi. He writes all the music in either Do pentatonic or La pentatonic and the songs or the Orff instruments use many different versions of Do, Re, Mi.

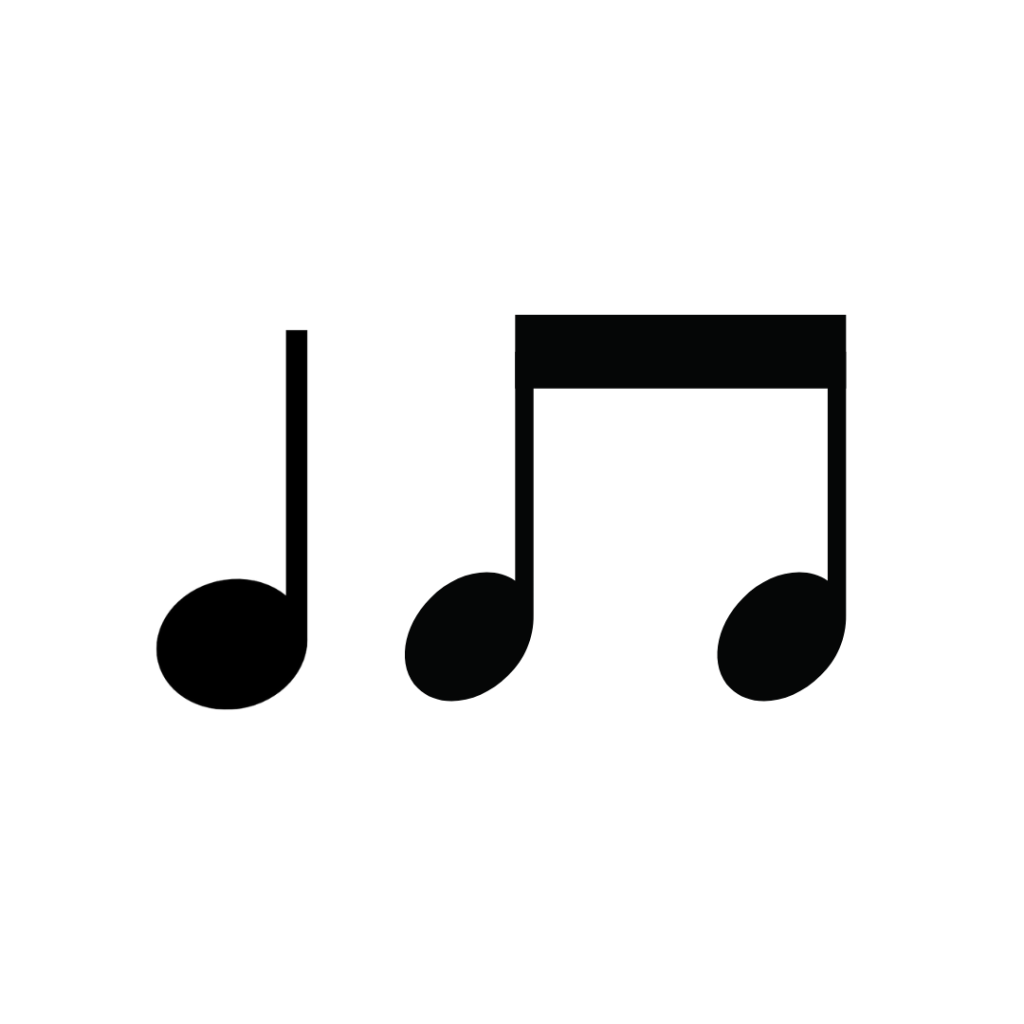

Example 2: Mr. McDowell teaches a lesson that leads the students to identify the rhythmic pattern of:

This is a repetitive pattern used in “High Hopes” by Panic at the Disco. He found a folk song that also uses this pattern but it expands upon it by adding other quarter notes, half notes, and quarter rests. The original song also used sixteenth notes but the grade he teaches has not learned how to identify these notes yet. In response, he changed these notes to a single quarter note and altered the lyrics to match the new rhythm.

Tips

- Choose music that teaches through experience and not long spoken explanations.

- Choose music that leads the learners to discovery.

- If you do not know if a song is appropriate for your students, pick a different song until you can remove all doubt.

Recommended Sources

Folk Songs:

- Anything by the New England Dancing Masters is golden. You can find many videos of the repertoire on YouTube: https://dancingmasters.com/shop/

- Music for Children American Versions. There are three volumes. Don’t get this confused with the British versions that are often used in Orff level training. https://www.musicmotion.com/9285-music-for-children-american-edition-vols-1-3-spiral-paperbacks

Popular Music:

- https://musicwill.org/

- Spencer Hale’s YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/@SpencerCHale

- Dr. Jill Reese Ukulele YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/drjillreese

- The Ukulele Lady on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@theukulelelady8732

- Dr. Vasil and Franklin Willis have many lessons specifically on popular music in elementary music. You will experience most of Dr. Vasil’s materials in this class or next semester.

MultiCultural Music

- https://folkways.si.edu/course-resources

- These folk dances are in three volumes and are AMAZING to use. You must purchase the actual CD to get the dance directions. It won’t be helpful to just get the mp3. Many teachers also have posted the dances on YouTube: https://www.amazon.com/Shenanigans-Folk-Dances-Terra-Australis/dp/B01MF5SAF4/ref=sr_1_2?qid=1691741147&refinements=p_32%3ASHENANIGANS&s=music&sr=1-2

Other Great Sources

- Orff Volumes I, II, IV, and sometimes III by Carl Orff

- Spielbuch für Xylophon I, II, and III by Gunild Keetman

- Discovering Keetman by Jane Frazee

- Intery Mintery by Doug Goodkin

- Now’s the Time: Teaching Jazz to All Ages by Doug Goodkin

- The Book of Canons by John Feierabend

- All books by the New England Dancing Masters

- Folk Songs North America Sings by Richard Johnston

- https://www.mamalisa.com for international folk music

- Homespun: Folk Songs of Rural America by Shirley McRae

- Jim Solomon books for drumming

- Hands to Hands: Hand Clapping Songs and Games from Around the World by Aimee Curtis Pfitzner

- Hands to Hands, Too! Hand Clapping Songs and Games from the USA and Canada by Aimee Curtis Pfitzner

- Countless notes from KOSA workshops and other Orff workshops

Supplementary Sources

- MusicPlay Online has a variety of good materials to use to get you started: https://musicplayonline.com/

- Quaver is being used in a lot of schools so it may be unavoidable. It has some good supplementary materials although many pieces inspired from “world music” are not properly credited or explained: https://www.quavered.com/login/

References

Barrett, J., McCoy, C., & Veblen, K. K. (1997). Sound ways of knowing: Music in the interdisciplinary curriculum. Schirmer Books.

Campbell, P. S. (2004). Teaching music globally. Oxford University Press.

Cicco, I. (2022). A historical perspective from folklorist Henry Glassie: Roots of folk songs in music education. Journal of Historical Research in Music Education, 44(1), 93–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536600621100

Green, L. (2002). How popular musicians learn: A way ahead for music education. Ashgate Publishing Group.