5 Teaching All Learners

Martina Vasil

Teaching All Learners

Every student is different, but regardless of their race, gender identity, ethnicity, social class, or ability, each should be treated with the same dignity and respect.

Research shows that it is likely that your future students will have a very different background from your own. There is a an increasing “demographic gap” between teachers (who tend to be White, female, middle class, and monolingual) and students (who tend to be students of color, low-income, and multilingual/limited English proficient).

While it may be difficult to be fully prepared to teach every learner who enters your classroom, you can do your very best to educate yourself and prepare yourself to teach students who come from a different background, heritage, and social identity from you. Understanding intersectionality and having a “critical consciousness” mindset are the best way music teachers—and all teachers—can be stepping up to ensure the comfort and safety of students. Being critically conscious means being aware of intersectionality and how certain identities are likely to face more challenges than others, depending on the context.

As a teacher, it is your responsibility to ensure every student feels safe, respected, and seen. Students likewise need to be educated on being kind and respectful to their peers.

Tips for Teaching All Learners

- Use Universal Design for Learning when crafting learning experiences.

- Understand that there are different kinds of learners: visual, aural/auditory, and tactile-kinesthetic.

- In a classroom, you will likely have 30% visual learners, 25% auditory, 15% tactile-kinesthetic, and 30% with a mixed modality.

- For students who best learn visually, small changes like incorporating technology, using a pictorial representation of the content, and using pictures in place of text can be beneficial.

- For the music classroom specifically, try using a listening map or printing/displaying the iconic or traditional staff notation for them.

- Show understanding and appreciation of differences and other cultures.

- Diversify your course materials (i.e., include a variety of genres and composers).

- Plan program music from different cultures.

- Introduce students to new sounds from different cultures.

- Ensure students from different cultures feel included.

- Do more with underrepresented creators.

- Acknowledge and take time to educate yourself on the proper adoption of customs, practices, or ideas of those who are typically less dominant in society. Research the history, cultural contexts, and performance practices of music written in multiple countries. Study the intent of educational, cultural, and musical outcomes of different pieces.

- Cultivate an inclusive, safe environment; maintain a respectful and supportive atmosphere for learning.

- Share sources of support with students.

- Be mindful of your language. For example, avoid gender-biased language such as “boys and girls.” Try “musicians” or “students” instead.

- Build rapport with your students; get to know them.

- Examine your own intersectionality and possible biases.

- Engage your classes in activities such as open conversations, where students take note of who and what is around them, and learn to simply be observant and be ready to learn from each other. That can make such a huge difference.

- Foster a growth mindset in students through providing specific, constructive feedback.

- Check out this podcast episode from Leading Equity about Individualistic vs collective cultures and the impact that can have on the classroom.

Culturally Relevant/Responsive Pedagogy (CRP)

Teachers must understand that each student’s backgrounds and experiences are different. Teacher should try to incorporate diverse values, experiences, and perspectives in curriculum.

With CRP, teachers focus on WHO they are teaching rather than WHAT is being taught.

- To help students develop academically

- To help students read, write, speak, and problem solve

- To support cultural competence at home and in the classroom

- To build on skills brought from the student’s culture

- To develop a critical consciousness

- To help students recognize, critique, and change social inequities

Remember that CRP is not limited to just race; each student will have different experiences regardless of race.

Example of Using CRP in General Music

- Use nursery rhymes and songs from different cultures (e.g., a Chinese rhyme about ladybugs).

- Use different cultural music to practice rhythms and melodies.

- Have a “cultures around the world” day; spend a day to go around class and experience many cultures.

- Use student-preferred music in the classroom. For example, this Fortnite Emote movement lesson that connects to student’s lives and love of playing video games.

Multi-Language Learners

It is important to realize that all children are inextricably connected to the language and culture of their home. It is important that you support and help them preserve their home-language usage. Also know that when MLLs first enter schools, they are experiencing quite a culture shock and may not want to talk to teachers and appear withdrawn. Be patient and kind. They are listening and practicing English in their minds. It does not mean they have a learning disability or lack of social skills. Imagine how you would feel going to school in a country where you did not know the language.

There are many ways children can show understanding beyond responding in English verbally or in written text. Children CAN and WILL learn English eventually even when they still use their home language. It is important to have various strategies to help multi-language learners understand the content you are teaching to help them learn.

First and foremost, show respect for your multi-language students and immediately involve them in meaningful, active music making experiences. There are plenty of opportunities to engage in music without using English, such as playing an instrument or moving their bodies (with you modeling nonverbally).

Get involved with MLL students. Research shows that teachers interact differently and less with MLL students. Don’t do that. Make the effort to get to know them and communicate with them. It’s quite easy to translate using Google on your phone or watch and make the time to connect with the student before and after classes when possible (or during lunch, recess, or car duty). Find out as much as you can about them and find ways to assist them. Learn a few phrases in their home language.

Don’t force MLLs to speak English in front of their peers.

Don’t publicly correct their pronunciation of words.

Maintain high expectations. A lack of knowledge of English does not mean a lack of understanding of music. Don’t give empty praises. Hold high expectations, which will motivate children to give effort and achieve musically.

Use peer interactions. Having students work in groups often increases motivation to learn, creates a positive learning environment, and leads to better understanding between students.

Incorporate their culture. Learning about the culture of your MLLs and bringing it into your curriculum in a respectful way is important. For example, don’t assume that all children who speak Spanish know the same songs. You may invite (but not EXPECT) MLLs to share a musical artifact or sing a song from their culture.

Use multiple forms of representation to get content across. For example, use images or hand gestures in addition to speaking the name of a musical concept.

Disabled Students

Ever since the incorporation of the “Education for All Handicapped Children Act” of 1975, it has been a requirement that educators provide equal opportunities for all students to succeed, which has led to two approaches: mainstreaming and inclusion (with inclusion being the favored approach, generally).

Mainstreaming is the practice of temporarily placing students with disabilities in a general classroom setting and being pulled out of the classroom for services. Inclusion gives disabled students a permanent place in the general classroom. Research has shown that this benefits not only disabled students, but also peers without disabilities. Inclusion places more of an emphasis on helping disabled students prepare for life and develop their social skills.

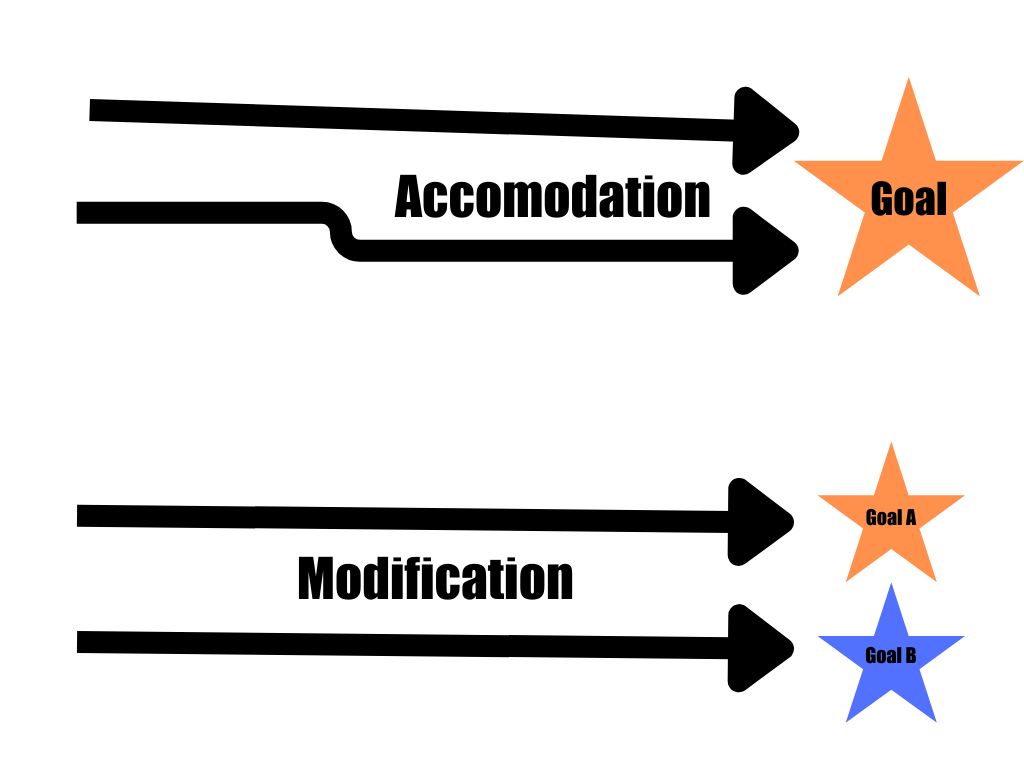

Music teachers use adaptations, or make changes in their instruction, to enhance student performance and increase participation. This can look like an accommodation or a modification in the classroom.

Accommodations are a change that helps a student work around their disability. This is reaching the same goal through different means. This might look like a teacher giving students visual cues in addition to spoken directions or allowing a non-verbal student to demonstrate an understanding of concepts using gestures rather than responding verbally.

Modifications are adjusting instruction and assessment so students are reaching different goals. This might look like a teacher allowing some students play a simpler part during an instrumental ensemble piece and only assessing them on that simpler part.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a great starting point when thinking about how to teach all learners in your classroom, whether you have students with some level of disability or not, which may include include cognitive disorders, behavioral disorders, language disorders, hearing or vision loss, or physical disabilities. In July of 2024, CAST (the organization that created UDL) released a new version, 3.0, of the CAST UDL Guidelines: https://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Adaptive Instruments and Manipulatives ensure all students have access to making music. The 3 Strings method uses colors and simplified chords to help all student learn. Discover more here: https://3strings.org/about/

Neurodivergent Students

You are likely to have neurodivergent students in your classroom (and you may be neurodivergent yourself). Types of recognized neurodivergence include dyslexia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and more. Tips for helping neurodivergent students:

- Have earplugs and noise-canceling headphones available to your students.

- Leave a safe space for students to distance themselves from noise.

- Allow frequent, short breaks for those who appear overwhelmed (drinks at the water fountain, short walks with an aide).

- Have small fidgets in a basket for those who need a different kind of stimulation (squishy toys, pop-its, etc.).

- Weighted vests and blankets can also be useful.

- As mentioned earlier in this book, Universal Design for Learning aids students with different learning styles and preferences (i.e., multi-sensory lessons, student-led learning, flexible assessments and providing multiple ways for a student to interact with a lesson’s material).

Recommendations for learners with autism. Autism Spectrum Disorder is a neurodevelopmental disorder that impairs a student’s social communication and interaction and presents as restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviors. I specifically delve into autism, because the chances are high that you will have a student with autism in your classroom. As of 2018, 1 in 59 children in the United States is diagnosed as being on the autism spectrum.

Studies have shown that learners with autism find school to be unpredictable and overwhelming and that they feel unwanted, unsupported, and unnoticed by their teachers. They want friends but are often bullied and isolated from their peers. Girls are less likely to be identified as on the spectrum because they often mask.

In elementary music, imitation is a primary way that teachers teach, yet autistic students cannot imitate with the same fluidity or understanding as their peers. Nonverbal students won’t be able to echo you when you sing phrases or chant a rhyme or poem.

Tips specifically for supporting autistic learners

- Be patient—learning through imitation is harder for autistic learners.

- Be flexible, no two students with autism will respond the same to teaching approaches.

- Use objects/instruments when possible. It is easier for students to perform movements when holding an object or instrument rather than copying a gesture or pantomiming. For example, if the class is pretending to row to “Row, Row, Row your Boat,” giving an autistic student rhythm sticks to hold while “rowing” is helpful.

- Repetition is helpful—over time, autistic learners will improve their fine and gross motor skills when imitating your movements and gestures.

- Mix the use of gestures with and without meaning. If you have movement to a song that don’t hold meeting, that can be hard for the student to follow or understand.

- Partner/group work can be challenging, create groups based on student interest, rather than randomly assigning students or letting them choose.

- Working with peers is preferred over direct instruction from the teacher.

- Imitate the student’s actions; they will be more social if you do. In other words, follow the child.

Recommendations for learners with ADHD from Dillon Bolon (MMME student at UK)

Teaching students with ADHD in the music classroom requires intentional strategies that balance structure, flexibility, and support. Because these students often learn best through active, hands-on experiences and short, varied tasks, teachers can enhance engagement in many ways:

- Provide accommodations in the music room, such as seating students with ADHD near the teacher, validating positive behaviors, providing enlarged text for vision needs, and encouraging eye contact during directions.

- Use movement and breaks—allowing physical movement (e.g., standing, crossing a doorway) can boost focus, memory, and processing.

- Curate a safe environments so ADHD students can “de-mask.” This reduces the mental strain of hiding symptoms and lowers risks of anxiety and depression.

- Adjust instructional strategies into brief, alternating activities.

- Teach self-regulation tools and self-care. Provide calm-down boxes, silent fidgets, or noise-reducing headphones help with under/overstimulation. Encouraging openness about ADHD fosters inclusion and reduces stigma.

References

Abril, C. (2003). No hablos inglés: Breaking the language barrier in music education. Music Educators Journal, 89(5), 38–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/3399918

de l’Etoile, S. K. (2005). Teaching music to special learners: children with

disruptive behavior disorders. Music Educators Journal, 91(5), 37–43.

https://doi.org/10.2307/3400141

Draper, A. R. (2021). Educational research for students with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Recommendations for music education. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 230, 22–46. https://doi.org/10.5406/21627223.230.02

Fitzwater, A. (2022, November 9). Neurodivergence and music: My experience. https://hub.yamaha.com/music-educators/prof-dev/teaching-tips/neurodivergence/

Hall, S. N., Spano, F. P., & Robinson, N. R. (2021). General music: A K–12 experience (2nd ed.). Kendall Hunt Publishing Company.

Hamdani, S. (2023). Self-care for people with ADHD. Adams Media Corporation.

McAllister, L.S. (2012). Positive teaching: Strategies for optimal learning with

adhd and hyperactive students. American Music Teacher, 61(4), 18–22.

Moore, P. (2009). Confronting ADHD in the music classroom. Teaching Music, 17(1), 57.

Salvador, K., & Culp, M. E. (20220). Intersections in music education: Implications of Universal Design for Learning, culturally responsive education, and trauma-informed education for K–12 praxis. Music Educators Journal, 108(3), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/00274321221087737

Scott, S. (2016). The challenges of imitation for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder with implications for general music education. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 34(2), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/8755123314548043