14

Timothy S. Reilly and Darcia Narvaez

There is increasing interest in the role of virtues in the development of scientists and in the practice of science, visible in scholarship on virtue epistemology,[1] epistemic cognition,[2] and intellectual and scientific virtue.[3] However, little research has tied this burgeoning interest into a more comprehensive psychological consideration of scientific character in light of virtue theory.

This paper begins to address this gap, presenting preliminary results from a survey of scientists’ conceptions of virtue and correlating them with personality traits relevant to virtue and character. We explored the relationship between conceptions of virtue and aspects of morality and ethics. Virtue, as defined in this paper, refers to an excellent disposition that allows individuals to achieve the ends relevant to their practices. A disposition refers to a tendency to act in certain ways in relevant situations, especially with regard to a practice domain.[4] As such, we adopt the lenses of personality and moral psychology in order to examine participant perceptions of virtue in science. Virtue is differentiated from character in that virtues are particular ideal qualities while character is the realization of such qualities in an individual. Thus, a person of “high” character is closer to the ideal of virtue than a person of “low” character.

Virtue and Moral Behavior

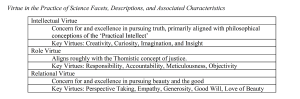

Recent research on virtues as traits has converged on a tripartite model of virtue: intellectual virtue, intrapersonal/self-regulatory virtue (e.g., self-control), and caring/interpersonal virtue.[5] But rather than discussing virtue at the abstract level of the decontextualized person, the present project explores virtue in practice, including intellectual virtue. However, in our prior work[6] we found that the caring aspect of virtue is, with scientists, perhaps better conceptualized as relational virtue, and that self-regulatory virtue, stemming from conversation with ethicists, may be better considered as role-related virtue. In addition, we assessed virtues in two ways, as general ideals for scientists (domain ideals) and as personal ideals. In sum, we examined three types of virtue (intellectual, relational, role-related) in two ways, according to the respondent’s ideals for self (personal ideals) and for the domain of science (domain ideals).

Scholars studying virtue and character are interested in the relevance of virtue traits to other aspects of moral and optimal functioning. Here we focused on (1) moral reasoning, (2) moral identity, (3) wisdom, (4) workplace climate, and (5) moral behavior. Each of these topics has received substantial attention, though these aspects of moral functioning have rarely been considered in concert with virtue ideals.

Beginning with the 1983 work of Kohlberg and his colleagues,[7] moral reasoning has been central to moral psychology for decades, though research suggests that in many cases it has only limited correspondence with moral behavior.[8] Despite its limitations, moral reasoning is associated with intellectual virtue, given its highly reflective cognitive nature. The Defining Issues Test (DIT)[9] has become a standard approach to assessing moral judgment development generally and its relation to performance in various domains. The DIT documents conceptions of fairness that develop toward greater inclusiveness with maturation and intense and diverse social experience.[10]

Moral identity, the centrality of moral concerns to the self-concept, helps bridge the gap between moral reasoning and action.[11] Moral identity is closely related to social perception, such as the chronic accessibility of constructs that guide behavior,[12] as well as to moral action.[13] Individuals with a strong moral identity are more likely to see situations in moral terms and to be strongly motivated to act in moral ways in these situations. Because moral identity concerns social values, we expect it to be most closely related to caring/interpersonal virtue ideals.

Wisdom has been a topic of research for some time, with varying conceptions emerging in the literature. We focus here on practical wisdom, adopting a definition that includes six components: (1) decision making, (2) emotional regulation, (3) pro-social orientation, (4) insight, (5) tolerance for divergent values, and (6) decisiveness.[14] We expected practical wisdom, while overlapping with intellectual and interpersonal virtue, to be most strongly associated with role-related virtue.

It is also important to consider the role of context when considering virtue because different situations call for different virtue expression. We focused our attention on three reliable aspects of ethical climate that have particular relevance to the practice of science: (1) self-interest (members of the lab are primarily interested in work for self-advancement), (2) team interest (members of the lab are interested in the good of the lab as a whole), and (3) public interest (members of the lab are interested in what is good for the field and the public).[15]

We also examined moral behavior. Whereas intellectual virtue, as commonly understood, may not relate directly to moral behavioral outcomes, intrapersonal and interpersonal virtue are presumed to be related to behavior. Two common measures of moral behavior in work contexts like that of laboratory science are organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), morally praiseworthy behavior in the organizational context, and counterproductive work behavior (CWB), which captures morally culpable behavior in the work context.[16] Using a psychological model of character, prior studies of these constructs demonstrated that greater character leads to more OCB and less CWB.[17] In addition, ethical climate moderates OCB, with a stronger ethical climate predicting more OCB.[18]

The Present Study

The aim of this study was to explore the nature of virtue ideals among scientists and relate those conceptions to other measures of morality and behavior. We developed a survey measure of virtue ideals for the practice of science,[19] assessing personal ideals and ideals for the domain of science. Factor analysis indicated three factors: intellectual, relational and role-related. Here we compared scores on this measure to scores on a variety of trait measures considered to be relevant to scientific virtue. Several research questions were explored. Do ideal conceptions of virtue relate to personality traits that can be considered virtuous in science and, if so, how? Do ideal virtue scores predict respondents’ self-reported moral behavior? Specific hypotheses were that (1) the intellectual virtue ideals would correspond most closely with scores on moral reasoning and wise insight, (2) role-related virtue ideals would correspond most closely with wise decisiveness and emotional regulation, and (3) relational virtue ideals would correspond most closely with communal imagination identity. We also predicted that (4) personal ideals would predict work behavior more strongly than domain ideals and that (5) personal ideals would predict work behavior over and above the effects of ethical climate.

Method

Participants and Procedure

A panel sample of 259 U.S. based laboratory scientists, recruited by Qualtrics, completed our survey. Roughly three-fifths of the scientists (n=156) worked in university settings and the rest in non-university settings (n=103). The sample was 64% male, ranging in age from 22 to 78 (M = 45.03, SD = 10.90). Participants reported being active in science for on average 21.4 years (SD=10.02); ethnicity was 51% white, 33% Asian American, and 16% other racial and ethnic backgrounds (combined percentage of African American, Native American, Hispanic/Latino, Immigrant, and Multiracial). Participants completed the survey online through Qualtrics survey software and were compensated monetarily for their time.

Measures

The Virtue Ideals in the Practice of Science (VIPS) measure was developed and validated by an interdisciplinary team of theologians, philosophers, science and technology studies scholars, and psychologists.[20] See Table 1 for a summary of the resulting constructs. The 30 items are administered in two ways, first with the following focus to elicit domain ideals for scientists generally (VIPS-DI): “How a good scientist ideally behaves within the laboratory.” The same items are administered with a focus on personal ideals (VIPS-PI): “How I would ideally behave in my scientific work.” Each item is presented with parenthetical descriptors, for example “Accountability (Holding others accountable to relevant norms and laws as appropriate)” and “Generosity (Voluntarily sharing time, resources, talents, or inventions).” The only direct mention of scientists and science is in the initial prompts for focus, and not in the items themselves. Prior analyses have indicated no significant effects of social desirability and ongoing analyses[21] indicate reliability and validity of these factors across multiple samples.

The survey also included personality and climate measures relevant to virtue and moral outcomes.

(1) For moral reasoning, we utilized a short form of the Defining Issues Test-2,[22] a measure of moral judgment development. The DIT is a multiple-choice measure where respondents rate and rank preferred types of moral reasoning (coded by personal interests, maintaining norms, or postconventional) in response to diverse hypothetical dilemmas. We used the most common score, the post-conventional score.

(2) For moral identity, we used Triune Ethics Orientation Communal Imagination,[23] which asks respondents to “Please respond to your views of how you are in SOCIAL SITUATIONS” and presents a short list of words representing a particular mindset. For Communal Imagination, the terms are “humanitarian, neighborly, inclusive, broad-minded.” The list of terms is followed by four statements regarding self-perception of those characteristics (e.g., “My friends think I have these characteristics;” “I strongly desire to be like this”) that respondents rate on a Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater affiliation with the ethical orientation.

(3) We used the San Diego Wisdom Scale (SD-WISE),[24] a Likert-type measure of wisdom with six subscales: (a) social advising (e.g., “I am good at perceiving how others are feeling”); (b) insight (e.g., “I avoid self-reflection”—reversed); (c) prosocial behavior (e.g., “I treat others the way I would like to be treated”); (d) tolerance for divergent values (tolerance; e.g., “I enjoy learning things about other cultures”); (e) decisiveness (e.g., “I usually make decisions in a timely fashion”); and (f) emotional regulation (e.g., “I have trouble thinking clearly when I am upset”—reversed).

(4) Climate measures were included to account for the influence of social context on pressures to act in prosocial and antisocial (roughly moral and immoral) ways. We measured workplace climate, specifically ethical climate, using adapted Ethical Climate subscales:[25] (a) self-interest (“In this lab people are mostly out for themselves”), (b) team interest (“The most important concern is the good of all the people in the lab,” and (c) public interest (“People in this lab have a strong sense of responsibility to the outside community.”) We also measured perceptions of social support.[26]

(5) Moral behavior was assessed with organizational citizenship behavior (OCB),[27] a measure of prosocial behavior within an organizational (typically work) context, and with counterproductive work behavior (CWB),[28] a measure of antisocial behavior within the same kind of context. Prior work suggests that these measures can be treated as measures of moral behavior.[29]

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

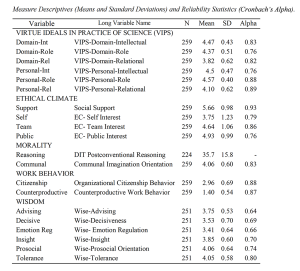

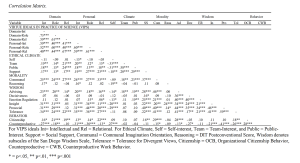

Descriptive statistics, correlations and reliability statistics (Cronbach’s alphas) for key variables were calculated including Virtue Ideals in the Practice of Science subscales: domain ideals (VIPS-DI) and personal ideals (VIPS-PI) and their three facets (intellectual, role, relational). Means, standard deviations, ranges, and alphas for measures are listed in Table 2. See Table 3 for correlations.

Virtue Ideals in the Practice of Science Regressions

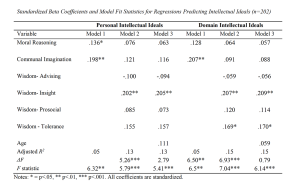

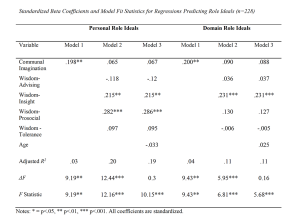

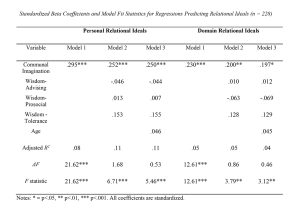

Regression models were used to test the strength of unique variance accounted for by predictors when combined. The models were constructed on each subscale of the Virtue Ideals in the Practice of Science measure (VIPS-DI, VIPS-PI) by facet (intellectual, role, relational). Based on theory and significant correlations, we set up three models to test across dependent variables. Model 1 included morality, specifically, communal imagination as the predictor (and included postconventional reasoning only for the intellectual virtue regression). Model 2 added wisdom (advising, insight, prosocial behavior, and tolerance), excluding decisiveness and emotion regulation given low correlations with the outcome variables (for relational virtue wisdom insight was excluded). The final model, Model 3, added age as a control variable to assess whether it accounted for significant variance beyond our hypothesized predictors. A regression was conducted for each dependent variable and these are presented as follows: intellectual virtue (personal, domain), role virtue (personal, domain), and relational virtue (personal, domain).

Intellectual virtue regressions are listed in Table 4. For personal ideals, Model 1 showed significant effects for post-conventional reasoning (β = .136, p < .05) and communal imagination (β = .198, p < .01). In Model 2 only wise insight (β = .202, p < .01) was a significant predictor. Age was not significantly predictive in Model 3, though wise insight (β = .205, p < .01) remained a significant predictor. Model 2 provided the best fit to the data (Adjusted R2 = .13, F(6, 195) = 5.79, p < .001). For domain ideals, Model 1 showed significant effects for only communal imagination (β = .207, p < .01). In Model 2 wise insight (β = .207, p < .01) and wise tolerance (β = .169, p < .05) were the significant predictors. Model 3 showed no significant effect of age, though wise insight (β = .209, p < .01) and wise tolerance (β = .170, p < .05) remained significant predictors. Model 2 also provided the best fit to the data for domain ideals of intellectual virtue (Adjusted R2 = .15, F(6, 195) = 7.04, p < .001).

Regression results for role virtue are presented in Table 5. For personal ideals, Model 1 included only communal imagination (β = .198, p < .01). Model 2 added wisdom (advising, insight, prosocial behavior, and tolerance), with wise insight (β = .215, p < .01) and wise prosocial behavior (β = .282, p < .001) as significant predictors. Model 3 added age, though wise insight (β = .215, p < .01) and wise prosocial behavior (β = .286, p < .001) remained as the only significant predictors. Model 2 showed the best model fit (Adjusted R2 = .20, F(5, 222) = 12.16, p < .001). For domain ideals, Model 1 included communal imagination (β = .200, p < .01) as the sole predictor. Model 2 added wisdom (advising, insight, prosocial behavior, and tolerance), with wise insight (β = .231, p < .001) the sole significant predictor. Model 3 added age, with wise insight (β = .231, p < .001) again as the sole significant predictor. Among the domain ideals models, Model 2 showed the best model fit (Adjusted R2 = .11, F(5, 222) = 6.81, p < .001). These results indicate that wise insight and prosocial behavior explained the most variance in personal ideals-role virtue ratings, and that when wisdom scales were included as predictors, they took up the variance accounted for by communal imagination. Age provided no additional variance coverage. VIPS-PI role virtue was predicted more reliably than VIPS-DI role virtue by these variables (see Table 5 to compare adjusted R2 and F).

Regressions for relational virtue are listed in Table 6. For personal ideals, Model 1 included only communal imagination (β = .295, p < .001). Model 2 added wisdom (advising, prosocial behavior, and tolerance), with communal imagination remaining the sole significant predictor (β = .252, p < .001). Model 3 added age, with communal imagination remaining the sole significant predictor (β = .250, p < .001). Model 1 showed the best model fit (Adjusted R2 = .08, F(5, 222) = 21.62, p < .001). For domain ideals, Model 1 included only communal imagination (β = .230, p < .001). Model 2 added wisdom (advising, prosocial behavior, and tolerance), but communal imagination was the only significant predictor (β = .200, p < .01). Model 3 added age, with communal imagination remaining the sole significant predictor (β = .197, p < .05). Model 1 showed the best fit for domain ideals (Adjusted R2 = .05, F(5, 222) = 12.61, p < .001). Across models, communal imagination predicted relational virtue explained the most variance though VIPS-PI relational virtue was predicted more reliably than VIPS-DI (see Table 6 to compare adjusted R2 and F).

Work Behavior Regression Models

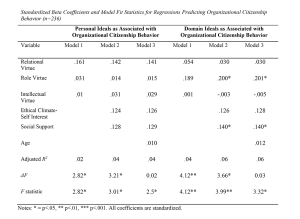

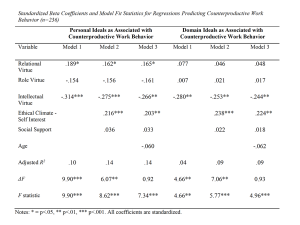

We also conducted hierarchical regressions on work behavior with citizenship behavior (OCB) and counterproductive work behavior (CWB) as dependent variables. See Tables 7 and 8.

Regressions for citizenship behavior (OCB) using VIPS scales as predictors began with Model 1, which included only VIPS personal ideals (relational, role, and intellectual). Model 2 added climate (self-interest and social support). Other ethical climate measures were excluded due to small and statistically nonsignificant correlations with CWB. Model 3 included age. Not much of the variance was accounted for in any of the models of personal ideals, and no predictors were significant.

We conducted a second regression on OCB where domain ideals (relational, role, and intellectual) were included in Model 1; none were significant. Model 2 added climate (self-interest and social support); role virtue (β = .200, p < .05) and social support (β = .140, p < .05) explained a significant amount of variance. Model 3 added age but no further variance was explained. Model 2 for domain ideals showed the best model fit (Adjusted R2 = .06, F(5, 230) = 3.99, p < .01). See Table 7.

Regressions for counterproductive work behavior (CWB) are listed in Table 8. Model 1 used VIPS scales as predictors (relational, role, and intellectual). Model 2 included climate (self-interest and social support). Other ethical climate measures were excluded due to insignificant correlations with CWB. Model 3 included age. For personal ideals, in Model 1 both intellectual virtue (β = -.314, p < .001) and relational virtue (β = .189, p < .05) were significant predictors. In Model 2, which added climate, self-interest (β = .216, p < .001), intellectual virtue (β = -.275, p < .001), and relational virtue (β = .162, p < .05) accounted for a significant amount of variance. Age added no predictive power in Model 3. Model 2 had the best model fit (Adjusted R2 = .14, F(5, 230) = 8.62, p < .001).

For domain ideals, Model 1 used VIPS scales as predictors (relational, role, and intellectual) of CWB. Only intellectual virtue was a significant predictor (β = -.280, p < .001). Model 2 added climate (self-interest, social support) and self-interest (β = .238, p < .001) accounted for significant variance with intellectual virtue (β = -.253, p < .01) remaining significant. When age was added in Model 3, no additional variance was accounted for. Model 2 for domain ideals had the best model fit (Adjusted R2 = .09, F(5, 230) = 5.77, p < .001). Domain-ideals for intellectual virtue and self-interested ethical climate accounted for a significant amount of variance in CWB. See Table 8.

Discussion

With a sample of scientists, we used a new measure, VIPS, which assesses virtue ideals and explored how ideal conceptions of virtue related to morality and behavior, using existing measures. Significant correlations between virtue ideals, personal and domain, and most measures were obtained. We conducted regression analyses, expecting that some of these relationships would prove more reliably predictive than others. The first hypothesis, that intellectual virtue would correspond with moral reasoning and wise insight, was supported, though wise tolerance for divergent values was also predictive of VIPS-DI intellectual virtue, and moral reasoning was not predictive in the best model. The prediction that role virtue would correspond most closely with decisiveness and emotional regulation was not supported. Instead, wise insight and (for VIPS-PI) prosocial behavior best predicted role virtue. Wise insight, as captured in the measure we used, corresponds largely with reflection and thoughtfulness, which may serve to mitigate problematic impulsiveness in fulfilling one’s role and ensure rigor in one’s thinking. Hypothesis 3, that relational virtue would correspond most closely with communal imagination, was supported.

Our second set of hypotheses concerned behavior. We found that virtue ideals ratings did in fact predict moral behavior, but that, with counterproductive work behavior (CWB), a measure of immoral behavior, personal ideals (VIPS-PI) were better predictors than domain ideals (VIPS-DI) when climate factors were taken into account. The hypothesis, that personal ideals would predict moral and immoral behavior more strongly than domain ideals, found partial support, as VIPS-PI did better predict lower levels of CWB. However, VIPS-PI did not predict citizenship behavior (OCB). Finally, we found support for our hypothesis that VIPS measures would predict CWB and OCB even when accounting for ethical climate, specifically intellectual virtue. We speculate that intellectual virtue endorsement reflects more intellectual advancement (since it was correlated with advanced moral reasoning). The fact that the variance explained by virtue ideals was small, especially for citizenship behavior, points to the complexities of moral behavior. Rest[30] explained the gap between moral reasoning and action with a four-process model where all processes must be enacted for moral behavior to ensue: perception and sensitivity to situation, judgment and decision making, motivation in the moment, and action skills (effectiveness and perseverance). Thus, having a set of ideals does not guarantee that one will or is able to act on them.

Taken as a whole, this study provides preliminary evidence for the usefulness of the two subscales of VIPS measures as assessments of virtue ideals in science. This sets the stage for future research that might extend their use to examine the relevance of the VIPS measures as they relate not just to moral behavior in the laboratory but other aspects of virtuous science, such as creativity, collaboration with international colleagues, ethical use of research materials, and treatment of research subjects, among other possibilities. Further, this study provides a starting point for the consideration of virtue in other practices, as the measure could be used in other domains, an important approach for grounding the study of virtue in particular contexts or domains.

Finally, the study provides evidence that consideration of personal scientific ideals may be important in understanding antisocial and unethical behavior in science, as such behavior constitutes counterproductive work behavior. This is to say that those who hold themselves to a higher personal standard are less likely to give themselves license to engage in misuse of an employer’s equipment and funds, intentionally fail to follow through on project timelines, miss work without cause, and/or demean others in the workplace. The study results suggest that researchers move beyond separating intellectual virtue and moral virtue to instead recognizing the ways that moral and intellectual virtue may be intertwined in scientific practice.

The present study has important limitations to consider. First, there was considerable diversity among the roles and experiences of laboratory scientists surveyed. As such, while the measure demonstrated reliability in the present sample, it may be helpful for future research to target scientists in particular roles to examine whether these findings hold across roles or whether they might pertain only to particular roles. For example, perhaps the findings apply more to scientists who continue to work at a lab bench than to those who supervise others’ research. Second, it was a self-report, cross-sectional study of volunteers. A random sampling of scientists would be preferable. In addition, most effects were quite small. Unmeasured but measurable factors may better account for much of the variation in VIPS scores and in reported work behavior. Future research could examine what additional factors might be important. It would also be interesting to study how perceptions change across time and experience in a particular laboratory. The present study cannot tease out causality. Are virtue ideals causes of other outcomes and/or do (and which) contextual features support or undermine virtue ideals? Such questions may be the seeds for future longitudinal work.

Conclusion

The present study provides evidence for the validity of virtues-in-science measures, considered both as ideals for the domain of science and as personal ideals. These two facets related to ratings of virtue ideals that were consistently predicted by measures of moral reasoning, wisdom, and moral imagination. Further, the study demonstrates that virtue ideals predict moral behavior, specifically greater organizational citizenship behavior and lower counterproductive work behavior.

TIMOTHY S. REILLY is Assistant Professor of Psychology at Ave Maria University and a former postdoctoral fellow with the Developing Virtues in the Practice of Science project. His work emerges from the intersections of developmental and learning sciences, with a special focus on the pursuit of a good life. Toward this end he has researched purpose, life design, entrepreneurship, psychological well-being, and virtue in adolescence and adulthood.

DARCIA NARVAEZ is Professor of Psychology at the University of Notre Dame; she focuses on moral development and flourishing from an interdisciplinary perspective. She is co-PI on the project Developing Virtues in the Practice of Science, supported by a grant from the Templeton Religion Trust. Dr. Narvaez’s current research explores how early life experience and societal culture interact to influence virtuous character in children and adults. She integrates neurobiological, clinical, developmental and education sciences in her theories and research about moral development. She publishes extensively on moral development, parenting and education. She is a fellow of the American Psychological Association and the American Educational Research Association. Her dozens of books and articles include Indigenous Sustainable Wisdom: First Nation Know-how for Global Flourishing (with Four Arrows, E. Halton, B. Collier, and G. Enderle); Embodied Morality: Protectionism, Engagement and Imagination; and Basic Needs, Wellbeing and Morality: Fulfilling Human Potential. Neurobiology and the Development of Human Morality: Evolution, Culture and Wisdom won the 2015 William James Book Award from the American Psychological Association and the 2017 Expanded Reason Award. She is on the boards of Attachment Parenting International and the Journal of Human Lactation. She writes a popular blog for Psychology Today (“Moral Landscapes”).

Bibliography

- Aquino, Karl, and Americus Reed. “The Self-Importance of Moral Identity.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83.6 (2002):1423–40.

- Baehr, Jason S. The Inquiring Mind: On Intellectual Virtues and Virtue Epistemology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Bargh, John A., Wendy J. Lombardi, and E. Tory Higgins. “Automaticity of Chronically Accessible Constructs in Person X Situation Effects on Person Perception: It’s Just a Matter of Time.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55.4 (1988): 599–605.

- Blasi, Augusto. “Bridging Moral Cognition and Moral Action: A Critical Review of the Literature.” Psychological Bulletin 88 (1980): 1–45.

- Chinn, Clark A., Ronald W. Rinehart and Luke A. Buckland. “Epistemic Cognition and Evaluating Information: Applying the AIR model of Epistemic Cognition.” In Processing Inaccurate Information: Theoretical and Applied Perspectives from Cognitive Science and the Educational Sciences, edited by David Rapp and Jason Braasch, 425–53. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014.

- Cohen, Taya R., and A.T. Panter. “Character Traits in the Workplace.” In Character: New Directions from Philosophy, Psychology, and Theology, edited by Christian B. Miller, R. Michael Furr, Angela Knobel, and William Fleeson, 150–63. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Cohen, Taya R., A.T. Panter, Nazli Turan, Lily Morse, and Yeonjeong Kim. “Moral Character in the Workplace.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 107.5 (2014): 943–63.

- Cullen, John B., Bart Victor, and James W. Bronson. “The Ethical Climate Questionnaire: An Assessment of its Development and Validity.” Psychological Reports 73.2 (1993): 667–74.

- Fox, Suzy, Paul E. Spector, Angeline Goh, Kari Bruursema, and Stacy R. Kessler. “The Deviant Citizen: Measuring Potential Positive Relations Between Counterproductive Work Behaviour and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 85.1 (2012): 199–220.

- Gresalfi, Melissa Sommerfeld. “Taking up Opportunities to Learn: Constructing Dispositions in Mathematics Classrooms.” The Journal of the Learning Sciences 18.3 (2009): 327–69.

- Hicks, Daniel J. and Thomas A. Stapleford. “The Virtues of Scientific Practice: MacIntyre, Virtue Ethics, and the Historiography of Science.” Isis 107.3 (2016): 449–72.

- Kohlberg, Lawrence, Charles Levine, and Alexandra Hewer. “Moral Stages: A Current Formulation and a Response to Critics.” Contributions to Human Development 10 (1983): 174.

- Lapsley, Daniel K. “Moral Stage Theory.” In Handbook of Moral Development, edited by Melanie Killen and Judith Smetana, 37–66. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2006.

- McGrath, Robert E., Michael J. Greenberg, and Ashley Hall-Simmonds. “Scarecrow, Tin Woodsman, and Cowardly Lion: The Three-Factor Model of Virtue.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 13.4 (2017): 373–92.

- Narvaez, Darcia. “Triune Ethics: The Neurobiological Roots of Our Multiple Moralities.” New Ideas in Psychology 26 (2008): 95–119.

- ——. Neurobiology and the Development of Human Morality: Evolution, Culture and Wisdom. New York: W.W. Norton, 2014.

- Narvaez, Darcia, and Patrick L. Hill. “The Relation of Multicultural Experiences to Moral Judgment and Mindsets.” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 3.1 (2010): 43–55.

- Narvaez, Darcia, and James R. Rest. “The Four Components of Acting Morally.” In Moral Behavior and Moral Development: An Introduction, edited by William Kurtines and Jacob Gewirtz, 385–400. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995.

- Narvaez, Darcia, Daniel K. Lapsley, Scott Hagele, and Benjamin Lasky. “Moral Chronicity and Social Information Processing: Tests of a Social Cognitive Approach to the Moral Personality.” Journal of Research in Personality 40.6 (2006): 966–85.

- Narvaez, Darcia, Alexandra Thiel, Angela Kurth, and Kallie Renfus. “Past Moral Action and Ethical Orientation.” In Embodied Morality: Protectionism, Engagement and Imagination, edited by Darcia Narvaez, 99–118. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2016.

- Park, Daeum, Eli Tsukayama, Geoffrey P. Goodwin, Sarah Patrick, and Angela L. Duckworth. “A Tripartite Taxonomy of Character: Evidence for Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, and Intellectual Competencies in Children.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 48 (2017): 16–27.

- Reilly, Timothy, Xiao Liu, and Darcia Narvaez. Virtue in the Practice of Science: A Three Wave Validation Study, manuscript in preparation, 2019.

- Rest, James R. “Morality.” In Cognitive Development, edited by John Flavell and Ellen Markham, 556–629. Manual of Child Psychology, Volume 3. New York: Wiley, 1983.

- Rest, James R., and Darcia Narvaez. Guide for Defining Issues Test-2. University of Minnesota: Center for the Study of Ethical Development, 1998.

- Rest, James R., Darcia Narvaez, Muriel Bebeau, and Stephen Thoma. Postconventional Moral Thinking: A Neo-Kohlbergian Approach. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1999.

- Rest, James R., Darcia Narvaez, Stephen J. Thoma, and Muriel J. Bebeau. “DIT2: Devising and Testing a New Instrument of Moral Judgment.” Journal of Educational Psychology 91.4 (1999): 644–59.

- Roberts, Robert C., and W. Jay Wood. Intellectual Virtues: An Essay in Regulative Epistemology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Shin, Yuhyung. “CEO Ethical Leadership, Ethical Climate, Climate Strength, and Collective Organizational Citizenship Behavior.” Journal of Business Ethics 108.3 (2012): 299–312.

- Spector, Paul E., Suzy Fox, Lisa Penney, Kari Bruursema, Angeline Goh, and Stacy Kessler. “The Dimensionality of Counterproductivity: Are All Counterproductive Behaviors Created Equal?” Journal of Vocational Behavior 68.3 (2006): 446–60.

- Thomas, Michael L., Katherine J. Bangen, Barton W. Palmer, Averria S. Martin, Julie A. Avanzino, Colin A. Depp, Danielle Glorioso, Rebecca Daly, and Dilip V. Jeste. “A New Scale for Assessing Wisdom Based on Common Domains and a Neurobiological Model: The San Diego Wisdom Scale (SD-WISE).” Journal of Psychiatric Research 108 (2017): 40–47.

- Walker, Lawrence J., Jeremy A. Frimer, and William L. Dunlop. “Varieties of Moral Personality: Beyond the Banality of Heroism.” Journal of Personality 78.3 (2010): 907–42.

- Zimet, Gregory D., Nancy W. Dahlem, Sara G. Zimet, and Gordon K. Farley. “The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.” Journal of Personality Assessment. 52.1 (1988): 30–41.

- Jason S. Baehr, The Inquiring Mind: On Intellectual Virtues and Virtue Epistemology (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011). ↵

- For example, Clark A. Chinn, Ronald W. Rinehart and Luke A. Buckland, “Epistemic Cognition and Evaluating Information: Applying the AIR Model Of Epistemic Cognition,” in Processing Inaccurate Information: Theoretical and Applied Perspectives from Cognitive Science and the Educational Sciences, edited by David Rapp and Jason Braasch (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014), 425–53. ↵

- Daniel J. Hicks and Thomas A. Stapleford, “The Virtues of Scientific Practice: Macintyre, Virtue Ethics, and the Historiography of Science,” Isis 107.3 (2016): 449–72; Robert C. Roberts and W. Jay Wood, Intellectual Virtues: An Essay in Regulative Epistemology (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007). ↵

- For example, Melissa Sommerfeld Gresalfi, "Taking Up Opportunities to Learn: Constructing Dispositions in Mathematics Classrooms," The Journal of the Learning Sciences 18.3 (2009): 327–69. ↵

- Robert E. McGrath, Michael J. Greenberg, and Ashley Hall-Simmonds, “Scarecrow, Tin Woodsman, and Cowardly Lion: The Three-Factor Model of Virtue,” The Journal of Positive Psychology 13.4 (2017): 373–92; Darcia Narvaez, “Triune Ethics: The Neurobiological Roots of Our Multiple Moralities,” New Ideas in Psychology 26 (2008): 95–119; Darcia Narvaez, Neurobiology and the Development of Human Morality: Evolution, Culture and Wisdom (New York: W.W. Norton, 2014); Daeum Park, Eli Tsukayama, Geoffrey P. Goodwin, Sarah Patrick, and Angela L. Duckworth, “A Tripartite Taxonomy of Character: Evidence for Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, and Intellectual Competencies In Children,” Contemporary Educational Psychology 48 (2017): 16–27; Willibald Ruch, “Character Strengths and Positive Outcomes in Different Life Domains,” paper presented at the Fifth World Congress on Positive Psychology, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2017. ↵

- Timothy Reilly and Darcia Narvaez, “Virtue and the Scientific Researcher: Understanding the Personality and Character of Scientists,” poster presented at the American Educational Research Association, New York, NY, 2018. ↵

- Lawrence Kohlberg, Charles Levine and Alexandra Hewer, “Moral Stages: A Current Formulation and a Response to Critics,” Contributions to Human Development 10 (1983): 174. ↵

- Daniel K. Lapsley, “Moral Stage Theory,” in Handbook of Moral Development, edited by Melanie Killen and Judith Smetana (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2006), 37–66; Lawrence J. Walker, Jeremy A. Frimer, and William L. Dunlop, “Varieties of Moral Personality: Beyond the Banality of Heroism.” Journal of Personality 78.3 (2010): 907–42. ↵

- James R. Rest and Darcia Narvaez, Guide for Defining Issues Test-2 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Center for the Study of Ethical Development, 1998). ↵

- Darcia Narvaez and Patrick L. Hill, “The Relation of Multicultural Experiences to Moral Judgment and Mindsets,” Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 3.1 (2010): 43–55; James R. Rest, Darcia Narvaez, Muriel Bebeau, and Stephen Thoma, Postconventional Moral Thinking: A Neo-Kohlbergian Approach (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1999). ↵

- Augusto Blasi, “Bridging Moral Cognition and Moral Action: A Critical Review of the Literature,” Psychological Bulletin 88 (1980): 1–45. ↵

- John A. Bargh, Wendy J. Lombardi, and E. Tory Higgins, “Automaticity of Chronically Accessible Constructs in Person X Situation Effects on Person Perception: It's Just a Matter of Time,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55.4 (1988): 599–605; Darcia Narvaez, Daniel K. Lapsley, Scott Hagele, and Benjamin Lasky, “Moral Chronicity and Social Information Processing: Tests of a Social Cognitive Approach to the Moral Personality,” Journal of Research in Personality 40.6 (2006): 966–85. ↵

- Karl Aquino and Americus Reed, “The Self-Importance of Moral Identity,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83.6 (2002):1423–40; Taya R. Cohen and A.T. Panter, “Character Traits in the Workplace,” in Character: New Directions from Philosophy, Psychology, and Theology, edited by Christian B. Miller, R. Michael Furr, Angela Knobel, and William Fleeson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 150–63. ↵

- Michael L. Thomas, Katherine J. Bangen, Barton W. Palmer, Averria S. Martin, Julie A. Avanzino, Colin A. Depp, Danielle Glorioso, Rebecca Daly, and Dilip V. Jeste, “A New Scale for Assessing Wisdom Based on Common Domains and a Neurobiological Model: The San Diego Wisdom Scale (SD-WISE),” Journal of Psychiatric Research 108 (2017): 40–47. ↵

- John B. Cullen, Bart Victor, and James W. Bronson, “The Ethical Climate Questionnaire: An Assessment of its Development and Validity,” Psychological Reports 73.2 (1993): 667–74. ↵

- E.g., Cohen and Panter, “Character Traits in the Workplace”; Taya R. Cohen, A.T. Panter, Nazli Turan, Lily Morse and Yeonjeong Kim, “Moral Character in the Workplace,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 107.5 (2014): 943–63. ↵

- Cohen and Panter, “Character Traits in the Workplace.” ↵

- Yuhyung Shin, “CEO Ethical Leadership, Ethical Climate, Climate Strength, and Collective Organizational Citizenship Behavior,” Journal of Business Ethics 108.3 (2012): 299–312. ↵

- Reilly and Narvaez, “Virtue and the Scientific Researcher.” ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Timothy Reilly, Xiao Liu, and Darcia Narvaez, Virtue in the Practice of Science: A Three Wave Validation Study (manuscript in preparation, 2019). ↵

- Rest, Narvaez, Bebeau, and Thoma, Postconventional Moral Thinking. ↵

- Darcia Narvaez, Alexandra Thiel, Angela Kurth and Kallie Renfus, “Past Moral Action and Ethical Orientation,” in Embodied Morality: Protectionism, Engagement and Imagination, edited by Darcia Narvaez (New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2016), 99–118. ↵

- Thomas, et al, “A New Scale for Assessing Wisdom Based on Common Domains and a Neurobiological Model.” ↵

- Cullen, Victor, and Bronson, “The Ethical Climate Questionnaire.” ↵

- Gregory D. Zimet, et al, “The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support,” Journal of Personality Assessment 52.1 (1988): 30–41. ↵

- Suzy Fox, et al, “The Deviant Citizen: Measuring Potential Positive Relations Between Counterproductive Work Behaviour and Organizational Citizenship Behavior,” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 85.1 (2012): 199–220. ↵

- Paul E. Spector, et al, “The Dimensionality of Counterproductivity: Are All Counterproductive Behaviors Created Equal?,” Journal of Vocational Behavior 68.3 (2006): 446–60. ↵

- Cohen and Panter, “Character Traits in the Workplace.” ↵

- James R. Rest, “Morality,” in Cognitive Development, edited by John Flavell and Ellen Markham, Manual of Child Psychology, Volume 3, edited by Paul Mussen (New York: Wiley, 1983), 556–629; Darcia Narvaez and James Rest, “The Four Components of Acting Morally,” in Moral Behavior and Moral Development: An Introduction, edited by William Kurtines and Jacob Gewirtz (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995), 385–400. ↵