Main Body

1 Chapter 1 – Critical Reading

Elizabeth Browning

When you are eager to start on the coursework in a major that will prepare you for your chosen career, getting excited about an introductory college writing course can be difficult. However, regardless of your field of study, honing your writing, reading, and critical-thinking skills will give you a more solid foundation for success, both academically and professionally. In this chapter, you will learn about the concept of critical reading and why it is an important skill to have—not just in college but in everyday life. The same skills used for reading a textbook chapter or academic journal article are the same ones used for successfully reading an expense report, project proposal, or other professional document you may encounter in the career world.

This chapter will also cover reading, note-taking, and writing strategies, which are necessary skills for college students who often use reading assignments or research sources as the springboard for writing a paper, completing discussion questions, or preparing for class discussion.

1. What expectations should you have?

3. Why do you read critically?

4. How do you read critically?

4.1 Preparing for a reading assignment.

4.2 Establishing your purpose.

4.4 While you read.

4.5 After you read.

5. Now what?

1. What expectations should you have?

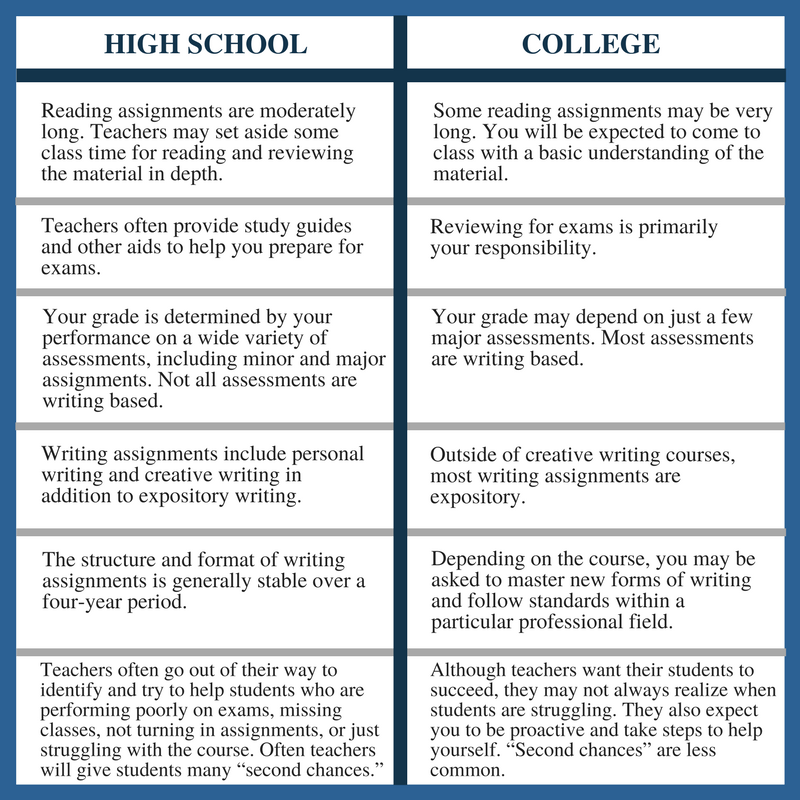

In college, academic expectations change from what you may have experienced in high school. The quantity of work expected of you increases, and the quality of the work also changes. You must do more than just understand course material and summarize it on an exam. You will be expected to engage seriously with new ideas by reflecting on them, analyzing them, critiquing them, making connections, drawing conclusions, or finding new ways of thinking about them. Educationally, you are moving into deeper waters. Learning the basics of critical reading and writing will help you swim.

Figure 1.1 “High School versus College Assignments” summarizes other major differences between high school and college assignments.

2. What is critical reading?

Reading critically does not simply mean being moved, affected, informed, influenced, and persuaded by a piece of writing. It refers to analyzing and understanding the overall composition of the writing as well as how the writing has achieved its effect on the audience. This level of understanding begins with thinking critically about the texts you are reading. In this case, “critically” does not mean that you are looking for what is wrong with a work (although during your critical process, you may well do that). Instead, thinking critically means approaching a work as if you were a critic or commentator whose job it is to analyze a text beyond its surface.

Tip:

A text is simply a piece of writing, or as Merriam-Webster defines it, “the main body of printed or written matter on a page.” In English classes, the term “text” is often used interchangeably with the words “reading” or “work.”

This step is essential in analyzing a text, and it requires you to consider many different aspects of a writer’s work. Do not just consider what the text says; think about what effect the author intends to produce in a reader or what effect the text has had on you as the reader. For example, does the author want to persuade, inspire, provoke humor, or simply inform his audience? Look at the process through which the writer achieves (or does not achieve) the desired effect and which rhetorical strategies he uses. These rhetorical strategies are covered in the next chapter. If you disagree with a text, what is the point of contention? If you agree with it, how do you think you can expand or build upon the argument put forth?

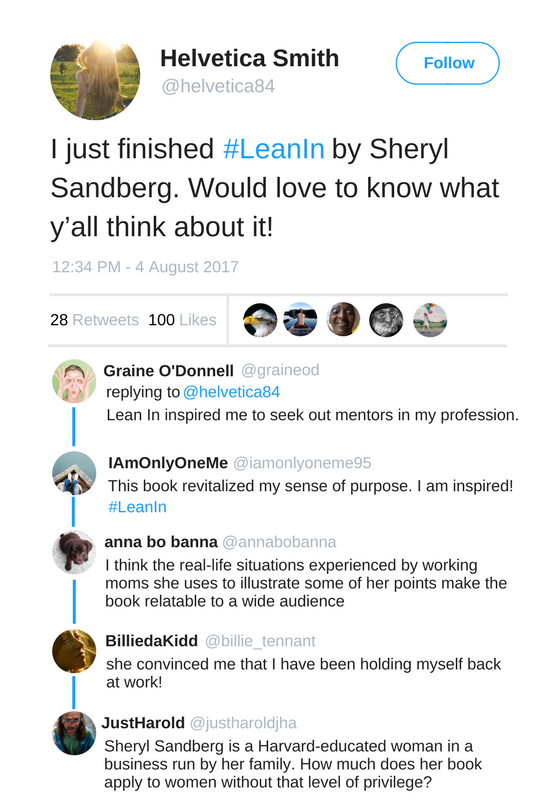

Consider this example: Which of the following tweets below are critical and which are uncritical? Figure 1.2 “Lean In Tweets”

3. Why do you read critically?

Critical reading has many uses. If applied to a work of literature, for example, it can become the foundation for a detailed textual analysis. With scholarly articles, critical reading can help you evaluate their potential reliability as future sources. Finding an error in someone else’s argument can be the point of destabilization you need to make a worthy argument of your own, illustrated in the final tweet from the previous image, for example. Critical reading can even help you hone your own argumentation skills because it requires you to think carefully about which strategies are effective for making arguments, and in this age of social media and instant publication, thinking carefully about what we say is a necessity.

4. How do you read critically?

How many times have you read a page in a book, or even just a paragraph, and by the end of it thought to yourself, “I have no idea what I just read; I can’t remember any of it”? Almost everyone has done it, and it’s particularly easy to do when you don’t care about the material, are not interested in the material, or if the material is full of difficult or new concepts. If you don’t feel engaged with a text, then you will passively read it, failing to pay attention to substance and structure. Passive reading results in zero gains; you will get nothing from what you have just read.

On the other hand, critical reading is based on active reading because you actively engage with the text, which means thinking about the text before you begin to read it, asking yourself questions as you read it as well as after you have read it, taking notes or annotating the text, summarizing what you have read, and, finally, evaluating the text. Completing these steps will help you to engage with a text, even if you don’t find it particularly interesting, which may be the case when it comes to assigned readings for some of your classes. In fact, active reading may even help you to develop an interest in the text even when you thought that you initially had none.

By taking an actively critical approach to reading, you will be able to do the following:

- Stay focused while you read the text

- Understand the main idea of the text

- Understand the overall structure or organization of the text

- Retain what you have read

- Pose informed and thoughtful questions about the text

- Evaluate the effectiveness of ideas in the text

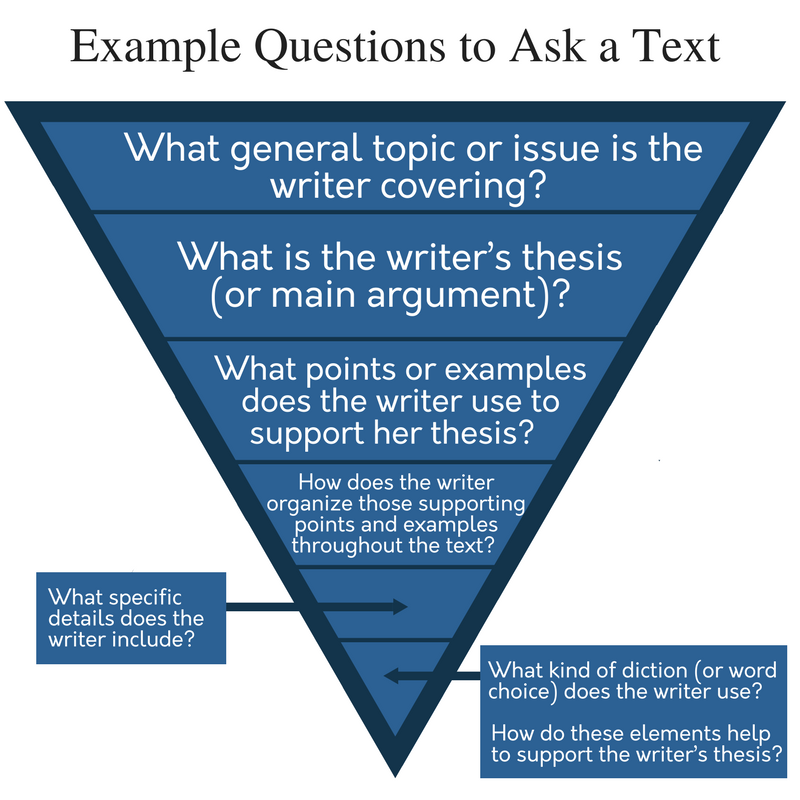

Specific questions generated by the text can guide your critical reading process. Use them when reading a text, and if asked to, use them in writing a formal analysis. When reading critically, you should begin with broad questions and then work towards more specific questions; after all, the ultimate purpose of engaging in critical reading is to turn you into an analyzer who asks questions that work to develop the purpose of the text.

Figure 1.3 “Example Questions to Ask a Text”

4.1 Preparing for a reading assignment

You need to make a plan before you read. Planning ahead is a necessary and smart step in various situations, inside or outside of the classroom. You wouldn’t want to jump into dark water head first before knowing how deep the water is, how cold it is, or what might be living below the surface. Instead, you would want to create a strategy, formulate a plan before you made that jump. The same goes for reading.

- Planning Your Reading

Have you ever stayed up all night cramming just before an exam or found yourself skimming a detailed memo from your boss five minutes before a crucial meeting? The first step in successful college reading is planning. This involves both managing your time and setting a purpose for your reading.

- Managing Your Reading Time

This step involves setting aside enough time for reading and breaking assignments into manageable chunks. If you are assigned a seventy-page chapter to read for next week’s class, try not to wait until the night before it’s due to get started. Give yourself at least a few days and tackle one section at a time.

The method for breaking up the assignment depends on the type of reading. If the text is dense and packed with unfamiliar terms and concepts, limit yourself to no more than five or ten pages in one sitting so that you can truly understand and process the information. With more user-friendly texts, you can handle longer sections—twenty to forty pages, for instance. Additionally, if you have a highly engaging reading assignment, such as a novel you cannot put down, you may be able to read lengthy passages in one sitting.

As the semester progresses, you will develop a better sense of how much time you need to allow for reading assignments in different subjects. Also consider previewing each assignment well in advance to assess its difficulty level and to determine how much reading time to set aside.

4.2 Establishing your purpose

Establishing why you read something helps you decide how to read it, which saves time and improves comprehension. This section lists some purposes for reading as well as different strategies to try at each stage of the reading process.

Purposes for Reading

In college and in your profession, you will read a variety of texts to gain and use information (e.g., scholarly articles, textbooks, reviews). Some purposes for reading might include the following:

- to scan for specific information

- to skim to get an overview of the text

- to relate new content to existing knowledge

- to write something (often depends on a prompt)

- to discuss in class

- to critique an argument

- to learn something

- for general comprehension

Tip:

To skim a text means to look over a text briefly in order to get the gist or overall idea of it. When skimming, pay attention to these key parts:

●Title

●Introductory paragraph, which often contains the writer’s thesis or main idea

●Topic sentences of body paragraphs

●Conclusion paragraph

●Bold or italicized terms

Strategies differ from reader to reader. The same reader may use different strategies for different contexts because her purpose for reading changes. Ask yourself “why am I reading?” and “what am I reading?” when deciding which strategies work best.

Key Takeaways

- College-level reading and writing assignments differ from high school assignments not only in quantity but also in quality.

- Managing college reading assignments successfully requires you to plan and manage your time, set a purpose for reading, practice effective comprehension strategies, and use active reading strategies to deepen your understanding of the text.

- College writing assignments place greater emphasis on learning to think critically about a particular discipline and less emphasis on personal and creative writing.

4.3 Right before you read

Once you have established your purpose for reading, the next step is to preview the text. Previewing a text involves skimming over it and noticing what stands out so that you not only get an overall sense of the text, but you also learn the author’s main ideas before reading for details. Thus, because previewing a text helps you better understand it, you will have better success analyzing it.

Questions to ask when previewing may include the following:

- What is the title of the text? Does it give a clear indication of the text’s subject?

- Who is the author? Is the author familiar to you? Is any biographical information about the author included?

- If previewing a book, is there a summary on the back or inside the front of the book?

- What main idea emerges from the introductory paragraph? From the concluding paragraph?

- Are there any organizational elements that stand out, such as section headings, numbering, bullet points, or other types of lists?

- Are there any editorial elements that stand out, such as words in italics, bold print, or in a large font size?

- Are there any visual elements that give a sense of the subject, such as photos or illustrations?

Once you have formed a general idea about the text by previewing it, the next preparatory step for critical reading is to speculate about the author’s purpose for writing.

- What do you think the author’s aim might be in writing this text?

- What sort of questions do you think the author might raise?

Sample pre-reading guides (Word Document downloads) – K-W-L guide (https://tinyurl.com/y9pvlw9k)· Critical reading questionnaire (https://tinyurl.com/y7ak9ygk)

4.4 While you read

Improving Your Comprehension

Thus far, you have blocked out time for your reading assignments, established a purpose for reading, and previewed the text. Now comes the challenge: making sure you actually understand all the information you are expected to process. Some of your reading assignments will be fairly straightforward. Others, however, will be longer and more complex, so you will need a plan for how to handle them.

For any expository writing—that is, nonfiction, informational writing—your first comprehension goal is to identify the main points and relate any details to those main points. Because college-level texts can be challenging, you should monitor your reading comprehension. That is, you should stop periodically to assess how well you understand what you have read. Finally, you can improve comprehension by taking time to determine which strategies work best for you and putting those strategies into practice.

Identifying the Main Points

In college, you will read a wide variety of materials, including the following:

- Textbooks. These usually include summaries, glossaries, comprehension questions, and other study aids.

- Nonfiction trade books, such as a biographical book. These are less likely to include the study features found in textbooks.

- Popular magazine, newspaper, or web articles. These are usually written for the general public.

- Scholarly books and journal articles. These are written for an audience of specialists in a given field.

Regardless of what type of expository text you are assigned to read, the primary comprehension goal is to identify the main point: the most important idea that the writer wants to communicate, often stated early on in the introduction and often re-emphasized in the conclusion. Finding the main point gives you a framework to organize the details presented in the reading and to relate the reading to concepts you learned in class or through other reading assignments. After identifying the main point, find the supporting points: the details, facts, and explanations that develop and clarify the main point.

Tip:

Your instructor may use the term “main point” interchangeably with other terms, such as thesis, main argument, main focus, or core concept.

Some texts make the task of identifying the main point relatively easy. Textbooks, for instance, include the aforementioned features as well as headings and subheadings intended to make it easier for students to identify core concepts as well as the hierarchy of concepts (working from broad ideas to more focused ideas). Graphic features, such as sidebars, diagrams, and charts, help students understand complex information and distinguish between essential and inessential points. When assigned a textbook reading, be sure to use available comprehension aids to help you identify the main points.

Trade books and popular articles may not be written specifically for an educational purpose; nevertheless, they also include features that can help you identify the main ideas. These features include the following:

- Trade books. Many trade books include an introduction that presents the writer’s main ideas and purpose for writing. Reading chapter titles (and any subtitles within the chapter) provides a broad sense of what is covered. Reading the beginning and ending paragraphs of a chapter closely can also help comprehension because these paragraphs often sum up the main ideas presented.

- Popular articles. Reading headings and introductory paragraphs carefully is crucial. In magazine articles, these features–along with the closing paragraphs–present the main concepts. Hard news articles in newspapers present the gist of the news story in the lead paragraph, while subsequent paragraphs present increasingly general bits of information.

At the far end of the reading difficulty scale are scholarly books and journal articles. Because these texts are written for a specialized, highly educated audience, the authors presume their readers are already familiar with the topic. The language and writing style are sophisticated and sometimes dense.

When you read scholarly books and journal articles, you should apply the same strategies discussed earlier. The introduction usually presents the writer’s thesis, the idea or hypothesis the writer is trying to prove. Headings and subheadings can reveal how the writer has organized support for his or her thesis. If the text contains neither headings nor subheadings, however, then topic sentences of paragraphs can reveal the writer’s sense of organization. Additionally, academic journal articles often include a summary at the beginning, called an abstract, and electronic databases include summaries of articles, too.

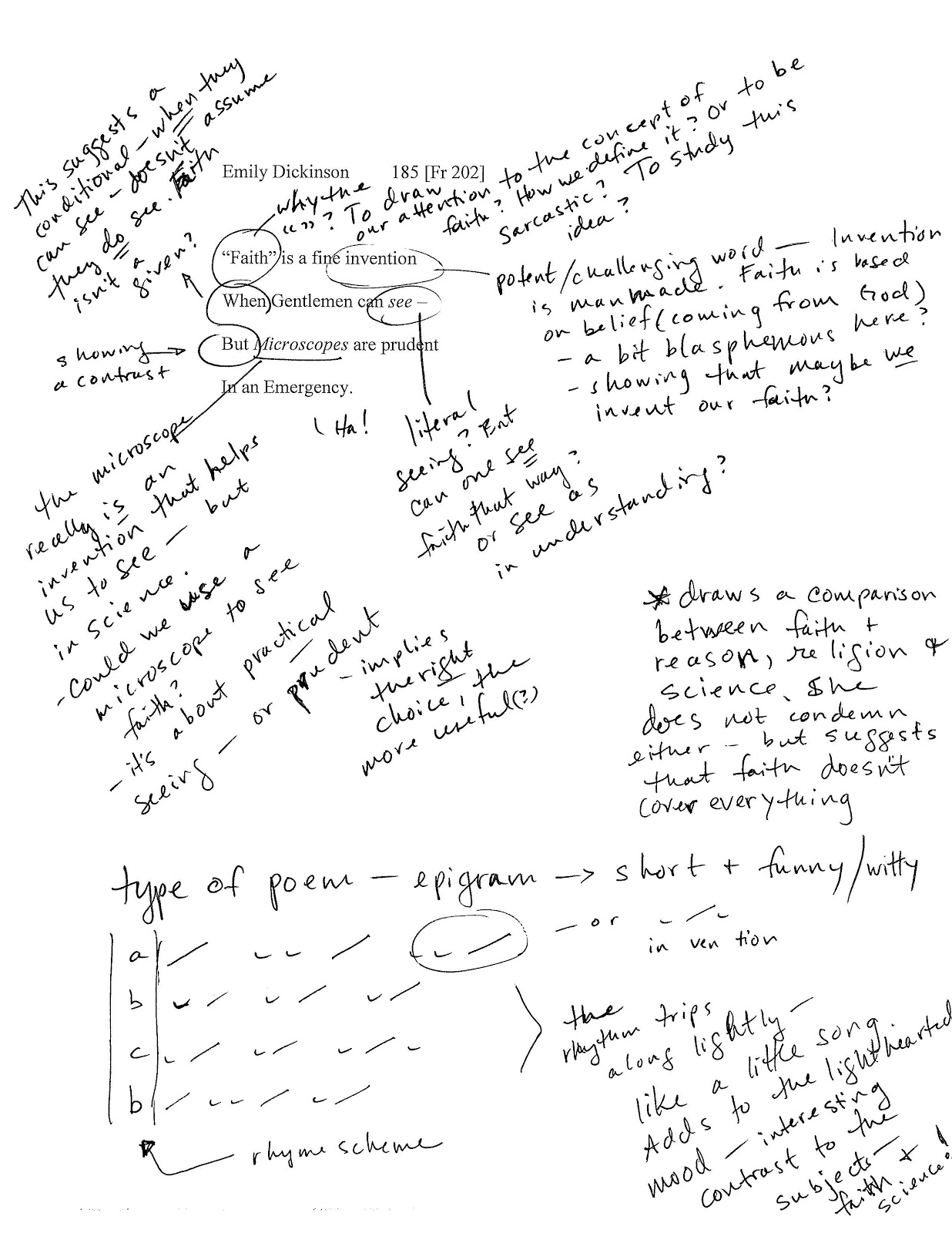

Annotating a text means that you actively engage with it by taking notes as you read, usually by marking the text in some way (underlining, highlighting, using symbols such as asterisks) as well as by writing down brief summaries, thoughts, or questions in the margins of the page. If you are working with a textbook and prefer not to write in it, annotations can be made on sticky notes or on a separate sheet of paper. Regardless of what method you choose, annotating not only directs your focus, but it also helps you retain that information. Furthermore, annotating helps you to recall where important points are in the text if you must return to it for a writing assignment or class discussion.

Tip:

Annotations should not consist of JUST symbols, highlighting, or underlining. Successful and thorough annotations should combine those visual elements with notes in the margin and written summaries; otherwise, you may not remember why you highlighted that word or sentence in the first place.

How to Annotate:

- Underline, highlight, or mark sections of the text that seem important, interesting, or confusing.

- Be selective about which sections to mark; if you end up highlighting most of a page or even most of a paragraph, nothing will stand out, and you will have defeated the purpose of annotating.

- Use symbols to represent your thoughts.

- Asterisks or stars might go next to an important sentence or idea.

- Question marks might indicate a point or section that you find confusing or questionable in some way.

- Exclamation marks might go next to a point that you find surprising.

- Abbreviations can represent your thoughts in the same way symbols can

- For example, you may write “Def.” or “Bkgnd” in the margins to label a section that provides definition or background info for an idea or concept.

- Think of typical terms that you would use to summarize or describe sections or ideas in a text, and come up with abbreviations that make sense to you.

- Write down questions that you have as you read.

- Identify transitional phrases or words that connect ideas or sections of the text.

- Mark words that are unfamiliar to you or keep a running list of those words in your notebook.

- Mark key terms or main ideas in topic sentences.

- Identify key concepts pertaining to the course discipline (i.e.–look for literary devices, such as irony, climax, or metaphor, when reading a short story in an English class).

- Identify the thesis statement in the text (if it is explicitly stated).

Links to sample annotated texts – Journal article (https://tinyurl.com/ybfz7uke) · Book chapter excerpt (https://tinyurl.com/yd7pj379)

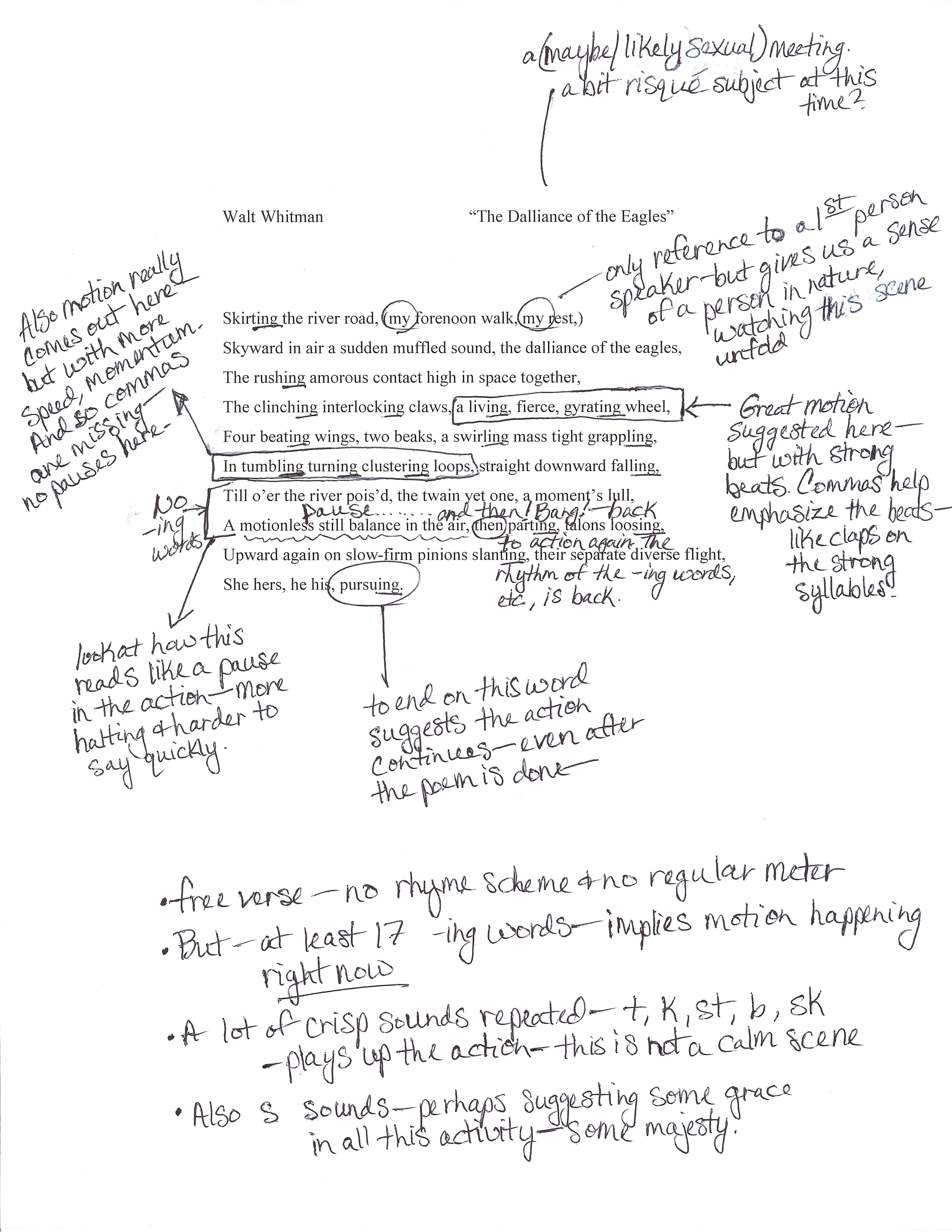

Figure 1.4 Sample Annotated Emily Dickinson Poem

Sample Annotated Emily Dickinson Poem

Figure 1.5 Sample Annotated Walt Whitman Poem “The Dalliance of the Eagles”

Sample Annotated Walt Whitman Poem “The Dalliance of the Eagles”

For three different but equally helpful videos on how to read actively and annotate a text, click on one of the links below:

“How to Annotate” (https://youtu.be/muZcJXlfCWs, transcript here)

“5 Active Reading Strategies” (https://youtu.be/JL0pqJeE4_w, transcript here)

“10 Active Reading Strategies” (https://youtu.be/5j8H3F8EMNI, transcript here)

4.5 After you read

Once you’ve finished reading, take time to review your initial reactions from your first preview of the text. Were any of your earlier questions answered within the text? Was the author’s purpose similar to what you had speculated it would be?

The following steps will help you process what you have read so that you can move onto the next step of analyzing the text.

- Summarize the text in your own words (note your impressions, reactions, and what you learned) in an outline or in a short paragraph

- Talk to someone, like a classmate, about the author’s ideas to check your comprehension

- Identify and reread difficult parts of the text

- Review your annotations

- Try to answer some of your own questions from your annotations that were raised while you were reading

- Define words on your vocabulary list and practice using them (to define words, try a learner’s dictionary, such as Merriam-Webster’s)

Critical Reading Practice Exercises

Choose any text that you have been assigned to read for one of your college courses. In your notes, complete the following tasks:

1. Follow the steps in the bulleted lists beginning under Section 3, “How do you read critically?” (For an in-class exercise, you may want to start with “Establishing Your Purpose.”)

- Before you read: Establish your purpose; preview the text.

- While you read: Identify the main point of the text; annotate the text.

- After you read: Summarize the main points of the text in two to three sentences; review your annotations.

2. Write down two to three questions about the text that you can bring up during class discussion. (Reviewing your annotations and identifying what stood out to you in the text should help you figure out what questions you want to ask.)

Tip

Students are often reluctant to seek help. They believe that doing so marks them as slow, weak, or demanding. The truth is, every learner occasionally struggles. If you are sincerely trying to keep up with the course reading but feel like you are in over your head, seek out help. Speak up in class, schedule a meeting with your instructor, or visit your university learning center for assistance. Deal with the problem as early in the semester as you can. Instructors respect students who are proactive about their own learning. Most instructors will work hard to help students who make the effort to help themselves.

Tip

To access a list of Virginia Western Community College’s learning resources, visit The Academic Link’s webpage (https://tinyurl.com/yccryaky)

5. Now what?

After you have taken the time to read a text critically, the next step, which is covered in the next chapter, is to analyze the text rhetorically to establish a clear idea of what the author wrote and how the author wrote it, as well as how effectively the author communicated the overall message of the text.

Key Takeaways

- Finding the main idea and paying attention to textual features as you read helps you figure out what you should know. Just as important, however, is being able to figure out what you do not know and developing a strategy to deal with it.

- Textbooks often include comprehension questions in the margins or at the end of a section or chapter. As you read, stop occasionally to answer these questions on paper or in your head. Use them to identify sections you may need to reread, read more carefully, or ask your instructor about later.

- Even when a text does not have built-in comprehension features, you can actively monitor your own comprehension. Try these strategies, adapting them as needed to suit different kinds of texts:

- Summarize. At the end of each section, pause to summarize the main points in a few sentences. If you have trouble doing so, revisit that section.

- Ask and answer questions. When you begin reading a section, try to identify two to three questions you should be able to answer after you finish it. Write down your questions and use them to test yourself on the reading. If you cannot answer a question, try to determine why. Is the answer buried in that section of reading but just not coming across to you, or do you expect to find the answer in another part of the reading?

- Do not read in a vacuum. Simply put, don’t rely solely on your own interpretation. Look for opportunities to discuss the reading with your classmates. Many instructors set up online discussion forums or blogs specifically for that purpose. Participating in these discussions can help you determine whether your understanding of the main points is the same as your peers’.

- Class discussions of the reading can serve as a reality check. If everyone in the class struggled with the reading, it may be exceptionally challenging. If it was easy for everyone but you, you may need to see your instructor for help.

CC Licensed Content, Shared Previously

English Composition I, Lumen Learning, CC-BY 4.0.

Rhetoric and Composition, John Barrett, et al., CC-BY-SA 3.0.

Writing for Success, CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0.

Image Credits

Figure 1.1 “High School versus College Assignments,” Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0, derivative image from “High School Versus College Assignments,” Writing for Success, CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0.

Figure 1.2 “Lean In Tweets,” Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0.

Figure 1.3 “Example Questions to Ask a Text,” Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0 .

Figure 1.4 “Sample Annotated Emily Dickinson Poem,” Kirsten DeVries and Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0.

Figure 1.5 “Sample Annotated Walt Whitman Poem ‘The Dalliance of the Eagles,’” Kirsten DeVries and Kalyca Schultz, Virginia Western Community College, CC-0.