1

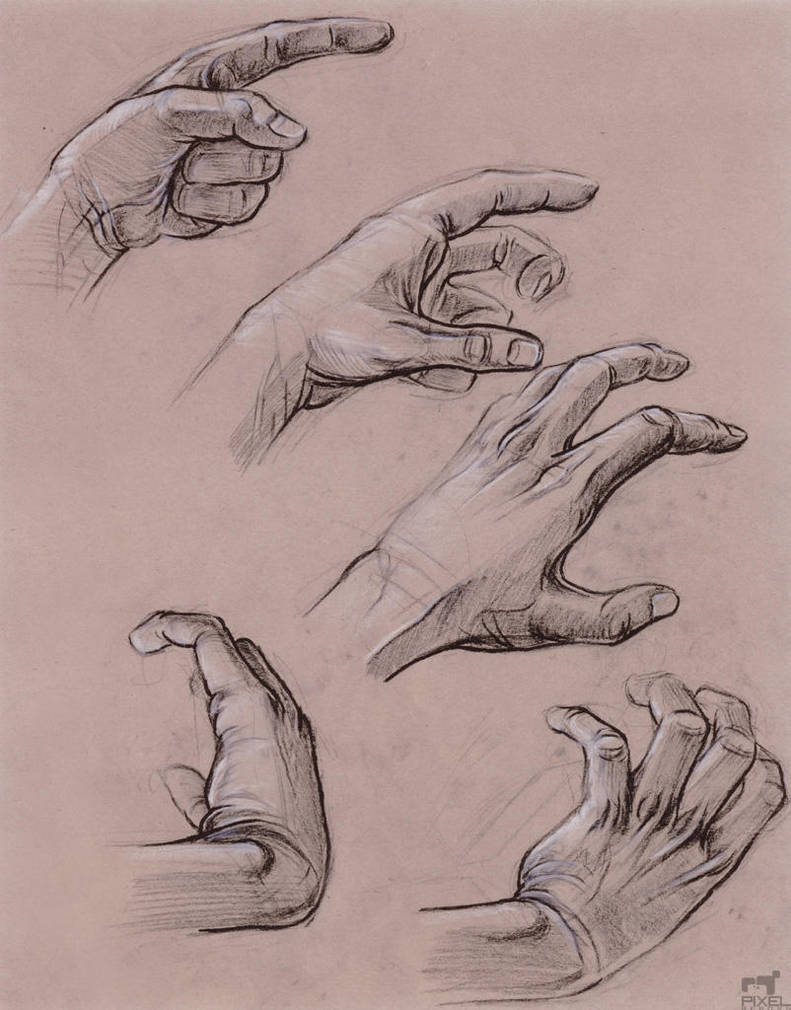

“Hand Study” by Liemn is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

This first unit will focus on some of the key elements of poetry. We will explore some common misconceptions about poetry that a lot of beginning writers have. We will read a bunch of poems by contemporary writers, as well as a few “classics.” At the end of this unit, you will have completed ten practice writing activities and one polished poem.

We will complete practice writing assignments #1, #4, and #8 in-class.

To Do List

□ Practice writing assignment 1.1: “And Still I Write”

□ Practice writing assignment 1.2: Chain poem

□ Practice writing assignment 1.3: Scar poem

□ Practice writing assignment 1.4: 10 topics

□ Practice writing assignment 1.5: Ugly poem

□ Practice writing assignment 1.6: Inspiration

□ Practice writing assignment 1.7: Inversion

□ Practice writing assignment 1.8: Line breaks

□ Practice writing assignment 1.9: 1st draft

□ Practice writing assignment 1.10: 2nd draft

□ Hand poem assignment 1.11: Final draft

An important note: Most of these initial assignments are designed to get you in the habit of putting pen to paper and to play with words. They are structured in such a way as to be as accessible to you no matter how much experience you have with reading or writing poetry. The key for these first ten days is to jump in with a sense of courage and curiosity.

Time to write, part one

Before we jump into defining poetry and figuring out how to write good poetry, let’s take a second to think about when we are going to write. (Here I’m using the “editorial we,” which really means “you.”) One of the hardest parts about writing is blocking out the time to write. Most of us don’t wake up in the morning and say, “Today’s a good day to write poetry.” We have other things to do. We are distracted by the latest tweetstorm. We want to return to the warmth of our pillows and the embrace of our sheets for just a few minutes more. But figuring out when you will fit your writing in this semester will increase your success. Rather than being reactive, let’s start to build a schedule where you can practice your writing daily.

So, go ahead and sketch out your typical weekly schedule:

| Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | |

| 6:00 | |||||||

| 8:00 | |||||||

| 10:00 | |||||||

| 12:00 | |||||||

| 2:00 | |||||||

| 4:00 | |||||||

| 6:00 | |||||||

| 8:00 | |||||||

| 10:00 | |||||||

| 12:00 | |||||||

| and later |

If you are like most DC students, this grid is now pretty full. Officially, you are supposed to spend 2 hours outside of class for every credit hour, or 6 hours per typical 3-credit hour class per week. (I know, you can stop snickering now.) What I am asking you is to find five 30-minute chunks, one per day. We will write some in class, so ideally you would pick days we don’t meet. Sometimes you won’t need this whole time; sometimes you might need a little more. What you are aiming for is to build into your schedule time to write before things start to get even more hectic.

What are the five times per week that you can commit to writing?

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

This commitment will help you be kind to your future self. Instead of panicking and trying to dash off a poem while snarfing down a breakfast burrito, you will be able to complete your task with less anxiety and stress. And, like any other practice, the more regularly you write, the easier it will be.

Time to write, part two

Now that we have a time to write, let’s start writing. Take five minutes and jot down a list of things you know about poetry: maybe a definition, maybe some techniques, maybe some poets, maybe just your reactions to the idea of poetry. Go ahead and fill up the box below. If you need more room, switch to another piece of paper.

|

|

Practice Writing Assignment #1.1 In-class “And Still I’ll Write”

Make a list of 6 or 7 reasons you can’t write or are afraid to write or have been told are reasons you can’t write well. Or add any of the things that inner-critic whispers when you try to put things down on the page. Skip every other line.

____________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________

Now, add in the line, “And still I’ll write” between each of these statements.

Defining Poetry (or not)

Poetry is one of those things that seems to hold two opposing definitions at the same time. People have rigid ideas about what a poem should be (often based on poems they read in school), and, at the same time, people have a sense that anything can be a poem. Some things are clearly poems: Shakespearean sonnets or haiku, for instance. But other pieces of writing that some people call poems look like paragraphs or sound like stories. Some poems are book-length and others look more like artwork than words on the page. How is a writer supposed to write a poem when the definition of a poem is so open-ended?

This textbook is not designed to give you a neat definition of poetry. Scattered throughout the text are a couple of handful of quotations from more accomplished poets about poetry. As you work your way through this book, pause on each of these definitions and allow them to push and pull on your own individual ideas about poetry.

What this course aims to do is to help you write better poetry. In order to do so, let’s start by addressing a few misconceptions about what poetry is. These ideas tend to limit the choices a writer can make, and can lead the writer to making choices that take away from the power and possibility of poetry. Imagine if you thought that all ice cream had to be a single flavor like vanilla, chocolate, or strawberry. You could still have a tasty frozen treat, but if you were to open yourself up to the idea that ice cream mix flavors than you could try a whole world of ice cream flavors like rocky road, mint chocolate chip, or Cherry Garcia.

Myth #1: Poetry has to rhyme

A lot of beginning writers think poetry has to rhyme. This isn’t a requirement for poetry. In fact, although for centuries poetry did usually follow some sort of rhyme scheme, most of contemporary poetry is written in free verse, which is unrhymed. Ironically, if you see poetry that rhymes, it may not be poetry at all. The rhymed writings of Shel Silverstein, Dr. Seuss, and those “poems” you see on social media might best be characterized as verse, and not true poetry at all. What’s the difference? We’ll try to show you here. First, read this sample we found online:

Our Love For You

Love is not a thing you get a lot

but love the girl you have got…

she is always there to care for you

the thing we have is oh so true….

She is so sweet and kind

and she’s the only girl on my mind….

our love is not a game

we love each other just the same….

She is my princess and my life

I can’t wait for the day to make her my wife….

then I can be with her 24/7

and she is the girl that I take to heaven….

#I LOVE MY GIRL

(from “15 Rhyming Love Poems for Her (Girlfriend)”)

Compare that to this poem, which was written in 1915 by Amy Lowell, one of the pioneers of the imagist movement. (We’ll talk more about that movement in a little bit.) While many poets rhymed 100 years ago, this one focuses more on the concrete, specific images and particular, contextual emotions and than on a metronome-like cadence and sing-song sounds. We think this is what good poetry does.

Vernal Equinox by Amy Lowell

The scent of hyacinths, like a pale mist, lies between me and

my book;

And the South Wind, washing through the room,

Makes the candles quiver

My nerves sting at a spatter of rain on the shutter,

And I am uneasy with the thrusting of green shoots

Outside, in the night.

Why are you not here to overpower me with your tense and

urgent love?

I believe that if someone wrote me the first piece it would feel like a nice gesture found in a store-bought card. Thanks for the thought; you’re too kind. But “Vernal Equinox?” If someone wrote that for me? Whew. It is powerful, vivid, meaningful, artistic, and surprising. Notice the juxtaposition (putting things next to each other) of the “thrusting green shoots” and the speaker’s longing for their lover’s “tense and urgent love.” Look at the ways that the “candles quiver” and the speaker’s “nerves sting at a splatter of rain.” Lowell’s poem isn’t trying to rhyme above everything else; it’s trying to show and feel. If you need to have some hashtags at the end to bring it up to date, might we suggest #Mood #Angst #Longing #Love.

So, rhyme can be an important tool, but if it is most important thing about a poem—or worse—the only thing in a poem, than it is likely that the poem will feel empty or trite. Rhyme can create emphasis or surprise; it can help with flow; it can make something memorable. But in and of itself, it does not make something a poem.

Practice Writing Assignment #1.2 Chain poem

- Pick a noun like clock, door, window, fence, light.

- Write down another that you associate with that word. (For instance, if your first word is party, you might think of the word friends or food or politics.)

- Now, write 5 to 7 more words responding to the last word you wrote. The list will hopefully move from the first idea to the last (sometimes a long way—that’s okay.) It shouldn’t just be a list of 6 to 8 synonyms. Instead, let your imagination roam.

- Now generate a poem that uses the words (in the order they appear), one of the listed words per line. You can add words before or after the list word. You can also change tense, turn singular nouns into plural, etc.

- Don’t plan in advance how the poem will end.

- Don’t rhyme unless it’s accidental.

- Underline the list words in each line.

Sample chain poem with the words mirror, reflection, sunlight, flower, petal, dirt, scrub

objects are closer than they appear

I glance into the side-view mirror before passing

the silver truck. The reflection of

the sunlight makes me wince.

I wonder if a flower feels the same way when a bee

softly lands on a petal, worried about the sting that might follow.

Miles of salt and dirt on the rear window hides my past,

unless I scrub it clean. Instead, I keep my eyes forward.

Myth #2: Poetry can mean anything you want it to

When you ask beginners who admire poetry what they like about it, they often answer something like this: “I like poetry because you can make a poem mean anything you want it to.” That’s another misconception. Although poetry is often difficult to interpret, and ambiguity (more than one meaning) is often a plus, poems should not be mounds of silly putty that can be shaped into anything you want to make of them. Some writers also seem to think that good poetry should be an empty canvas that the reader can decide what it is really about. These approaches often end up with poems that end up being about so many things that feel like they are about nothing at all.

Here’s an example from a good high school literary magazine. (I’m not trying to dump on high school writers. But it is a good example of what I’m talking about.)

Maelstrom

Running in circles

chasing yet never defining

the pattern is infinitely stagnant

and though you see the light,

the truth never comes

for the mucky water never clears

but flows on to an

untimely life

in which all is different

You aren’t there,

no one is

and I am free.

This poem is not without merit. After all, some fairly sharp student literary magazine editors chose it to include in their yearly volume. In particular, the poem has two moments of surprise–unexpected inversions of the usual: “infinitely stagnant” plays off the cliché “infinitely changing” nicely, in a manner similar to the way “untimely life” is a fairly novel inversion of “untimely death.” Not bad. Another clever aspect of the poem is its shape. In mimicking the maelstrom, not exactly, but suggestively, the poem attempts to be, in some way, concrete.

Now, what exactly is the problem with this poem? Let’s begin with the obvious question. Take a moment to write what you think this poem is about.

Okay, did you get it? Well, there’s clearly no “it” here, and that in itself is not bad, especially in poetry. When I asked other students the same question, here’s some of what they said:

- a relationship that went bad

- depression

- the impossibility of achieving world peace

- friends who lie to you

- nuclear war

- the situation in the Middle East

- a whirlpool

- childbirth

- mental illness

The student responsible for number seven is something of a literalist. A maelstrom is “a large or violent whirlpool,” according to Webster’s. A secondary meaning, equally valid here, is “a violently confused, turbulent, or dangerously agitated state of mind, emotions, affairs, etc.” Notice how this last definition works pretty well as a metaphor for most of the first six interpretations. That’s good, but too good. If we, as readers, can’t make some specific sense out of the poem, the poet usually has not done their job. We say usually, because…well, there is that exception to every rule. We’ll look at that later.

Can you see what the problem is with a poem that generates nine disparate meanings such as the above? A writer’s business is communication. Even if the poetry isn’t strictly getting a message across, the idea is to get some idea from the poet’s brain to the readers. But whatever idea the “maelstrom” poet had is lost in these layers of potential meaning. There’s not much for the reader to grab onto here.

Poetry such as the above has been allowed to proliferate in the modern era as a backlash to poetry of a previous era, which absolutely had to mean something. The poetry of such classic writers as Alexander Pope and Ralph Waldo Emerson was more like an argument in rhyme than it was like poetry we might be more used to today. In fact, Emerson defined poetry as “meter-making argument,” to distance himself from those, like Edgar Allan Poe, who were trying to create rhythmic beauty. This doesn’t mean either poet is wrong (though they each thought they were undoubtedly correct) but that their conception of poetry is different. This shouldn’t be difficult to understand if you employ the analogy of music. There’s hip-hop, alt-folk, EDM, and classical, etc., etc., etc….At times they don’t seem to have much to do with each other, and you may like some musical genres more than others, but we have to admit that they’re all music.

To return to our discussion of meaning in poetry, in the twentieth century many poets rebelled from the concept of a poem being a forum for ideas, and decided that a poem, in the famous words of poet Archibald MacLeish “should not mean, but be.” In other words a poem did not have to have a specific meaning. It should exist as an artistic entity like a sculpture of a torso or a postmodern building downtown, but it does not have to have a meaning. Good idea, if applied within reason. But in less-skilled hands, what a riot of worthless words Archibald’s pronouncement has helped to unleash. Ironically, the poem, “Ars Poetica” in which MacLeish coined his famous phrase, is something of an argument: “A Poem should be palpable and mute/as a globed fruit…” he begins. Sounds like it has meaning to me. What’s the point then, of not mean, but be, if even Archy can’t do it?

A group of writers called the imagists has a similar idea. The Pulitzer Prize winning poet, editor, and translator Amy Lowell wrote a preface in Some Imagist Poets that spelled out the principles of this movement. Imagists strove to use “the exact word, not the nearly-exact, nor the merely decorative word.” They emphasized writing about “modern life” and not relying on the topics and ideas of the past. Additionally, Lowell described a couple of other principles that we find pretty timely today:

- “…we believe that poetry should render particulars exactly and not deal in vague generalities, however magnificent and sonorous.”

- “Finally, most of us believe that concentration is of the very essence of poetry.”

In terms of the last point, Lowell is using “concentration” to mean the paring down the language to its most potent level (think of concentrated orange juice) rather than the mental effort to pay attention (although the Imagists would advocate for close observation).

“There should be no ideas but things,” William Carlos Williams said in 1927, summing up the imagist primary methodology. In other words, don’t state your ideas, put things in your poem that will make ideas come across. In still other words, the most quoted words in creative writing courses from the Redwood forests to the New York island, SHOW, DON’T TELL. You’ll hear us recite this one again (and again, and again…). Williams was suggesting that poets paint pictures with words, create vivid, lively images that readers can see, smell, taste, touch, feel. And there’s nothing wrong with that. In fact, it’s the way to go, the only way for beginning writers to go, as far as we’re concerned. In creative writing, it’s what separates the professional writer from the amateur. SHOW, DON’T TELL. Show the sweat dripping from your protagonist’s forehead; don’t say “it was hot.” Show the bruises on his face, the welts, the purple-brown raccoon mask surrounding his eyes; don’t say “he was in a fight.”

We’ll return to this idea often. For now, since the problem with our maelstrom poet is not primarily an absence of images, why doesn’t the poem add up to a rich, evocative experience? With all respect to MacLeish, a poem does usually need to mean something, anything, and if it means too little or too much (as in the case of our example), the aesthetic experience tends to be compromised. What our maelstrom poet needs more than anything is a layer of meaning, literal or otherwise, that everyone can agree on. The poem, like a human body, needs a skeleton. Like a sub-atomic particle, it needs a nucleus. Like a skyscraper, it needs a framework. Around that skeleton, nucleus or framework, the poet can build on any images, meanings, metaphors, whatever. But there has to be some central core of meaning.

Practice Writing Assignment #1.3 Scar poem

Scan your body for a scar or mark. Write a short poem (5-10 lines) that begins with that image or the event that is connected to it. Don’t worry about having a “deep” meaning. Instead, focus on the showing us that moment or the result of that moment.

Myth #3: Poems don’t need titles

Now, this might not be a myth at the same level as the previous two, but I do see it a lot. Maybe new writers never get around to creating a title. Maybe they think “Assignment #1” is good enough. But like the other myths, this belief (or practice) misses out on some prime real estate of a poem.

Let’s return to our maelstrom poem. You might say that the maelstrom is the skeleton, and, to some degree, it is. But a maelstrom of what? Water? Emotions? The reader just doesn’t know. Say that someone wants to argue that the poem is about a flushing toilet. Can we really refute this concept? “Running in circles,” “mucky water” flows on. Eesh.

Try this exercise. Come up with a title for the poem.

Here’s some of mine:

- “Lonely Night, January 27, 2003.”

- “Senate Debates”

- “CDC Advice about COVID-19”

- “Turmoil in the Ukraine”

- “Toilet Bowl”

They all work, sort of, don’t they? That’s a problem. The poem is so vague, almost an attempt to disguise rather than divulge meaning, that it can be interpreted in any way a reader wants.

The title is a place to steer the reader to where you want them to go. Or, to create some expectations that you can either fulfill or push back against. It can signal the tradition of the poem or connect it to another poem. It is the first thing the reader will see, so don’t give up that opportunity. Think of the title as the first line of the poem.

If you don’t give your poem a title, the convention is to use the first line of the poem as the title. This is what we do with Emily Dickinson poems, and what we did with “Maelstrom.” But it’s your poem. You should get to name it.

Myth #4: If you want to write about personal matters in a poem, disguise them through metaphors

Sometimes writers want to explore something very private and personal but don’t want to reveal any details. They end up writing poems that feel like the “Maelstrom” poem. Or, they use elaborate metaphors that leave the readers scratching their heads. While using powerful, emotional events as the start of a poem can be effective, you need to make sure that you want to go there. Obscuring the details obscures the emotion. Without something concrete to hold on to, we can’t latch on to the poem, and then we are just left with “murky waters.”

Some writers mine their own experiences to create moving poetry. These poets write what is called “confessional poetry,” and some if it is pretty shocking in how vulnerable it is. Here’s an example of Olds’ confessional poetry (although she calls it “apparently personal” poetry.)

Olds’ speaker–who we really want to call Olds herself, but we know is just a part of Olds, an invention, a stand-in, or a sliver of herself–digs into the pain of loss. We know that Olds went through a divorce and held off writing about the experience for a few years. We know that she has talked about her ex-husband publicly. And so this poem feels “apparently personal.” The poem explores the pain of having her husband leave. The speaker makes the comparison between those who are separated by death “driven/against the grate of a mortal life” and those who are distanced by divorce (“the slowly shut gate/of preference.”) But it isn’t just a sense of loss. Olds writes, “my job is to eat the whole car/of my anger, part by part, some parts/ground down to steel-dust.” Pause on that image for a moment: visualize ingesting the whole engine block, bucket seats, steel-belted tires, doors, rear-view mirror, and windshield wiper of a vehicle of your anger, of the car that symbolizes the time spent with that person. That’s something.

Also, notice what happens if you take out the first clause, “When my husband left.” We don’t have anything to grab hold of. Just that little bit signals to us that this is about marriage (and we later discover) divorce. Or, if we substitute that with “when my dog ran away,” it is a different poem entirely. Olds doesn’t want to write a poem about loss in general, but about the loss of divorce, and in particular, her divorce.

And many of Olds’ earlier poems are even more starkly personal: poems about abuse, alcoholic fathers, and Electra complexes. I don’t think Sharon Olds or anyone else, probably, could write such a tell-all, bare-your-soul piece in an introductory creative writing class, and to tell you the truth, we don’t really want to encourage it. But don’t hide your people and events behind nebulous imagery that only serves to obscure the facts. No one can relate to such poems, because we haven’t really been given anything to relate to.

Practice Writing Assignment #1.4 In-class

Make a list of 10 potential topics you could write about: people, events, questions, moments of discovery, oddities, things that piss you off, etc.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

Now, pick one and write for 10 minutes. Aim for a poem that is specific and has a title.

Myth #5: Poetry needs to be pretty

Some writers think that poetry needs to explore love or the beauty of nature. Sure, there are a lot of really great love poems, and just about every poet has a piece about birds or sunsets or the rain. And those are things that are sublime and move us. Those are things that need powerful and artful language to describe, but there are a whole lot of other topics that poetry can investigate.

So, what can you write about? Just about anything. Here’s a poem by William Brewer about his home state of West Virginia in the wake of the opioid crisis.

Brewer’s poem is not pretty. It’s from a collection of poems called I Know Your Kind, which won the National Poetry Series Award. Brewer focuses on his home state of West Virginia, especially in the wake of the opioid crisis. The title of this poem is a play on the town Oceana, West Virginia, which had a high rate of Oxycontin overdoses. The images are a far cry from the John Denver (yes, I know I’m dating myself) hit “Take Me Home, Country Roads,” which begins, “Almost heaven, West Virginia.” Brewer depicts a landscape of “fog-strangled mornings,” “the pink heads of rhododendrons/lopped off by the wind,” and “poisoned trees/black like charred bones.” The speaker describes a place where faith has been replaced with the sounds of ambulances responding to overdoses: “where once there was faith,/there are sirens: red lights spinning/door to door, a record twenty-four/in one day.”

The poem has some powerful lines (“Pin oaks arm-wrestle over the house/as barrel fires spark like stars in the valley/and the day closes its jaws”), a devastating message, and even an interesting allusion to Jonah and the whale, but we would never mistake this as pretty poetry.

Jericho Brown won the Pulitzer in 2020 for his collection, The Tradition. This is one of the more haunting poems:

So far in this chapter, we’ve exposed a number of common myths about poetry:

- Poetry must rhyme.

- A good poem can be understood to mean anything the reader wants it to mean.

- It’s edgy to write poems without titles.

- If you want to write about personal matters in a poem, disguise them through metaphors.

- Poetry must be pretty.

Practice Writing Assignment #1.5 Ugly poem

Write a poem about something gross. Think about something small rather than something global. For instance, someone clipping their toenails in public rather than genocide. Focus on creating a picture that will make the reader respond with a shiver.

There are, as we all know, exceptions to every rule. We could probably go through each of these five myths and give you examples of how various great poets have broken these rules. For example, there is an entire school of poets, called the new formalists, who write poetry that rhymes, or if it doesn’t, use sound techniques and verse forms that are very close to traditional poetry. Earlier we mentioned that even a “maelstrom” poem can be successful given the right circumstances. Here’s one of the best “maelstrom” poems we’ve seen, written by former United States poet laureate Mark Strand:

We could ask a lot of questions about this poem. What, besides a person in a field, is it about? Is it metaphorical? If so, for what? But in some ways, it’s better just to feel this one. If MacLeish’s statement about a poem not meaning but being is anywhere true, Strand’s piece is an example. If you can’t tell what makes this brilliant little gesture rise above “maelstrom” don’t worry too much. Poetry is a bit like broccoli. You’ve got to develop a taste for it before you can tell good broccoli from bad. “Keeping Things Whole” is Strand’s most famous poem. An awful lot of readers of poetry think it’s a tiny masterpiece. You may need to read a lot more poetry to figure out just why, however.

But again, mostly I discourage “maelstrom” poems, poems that do not seem to be about anything. Conversely, I encourage you to write specifically and vividly about real things, events, issues, people. This is not a lesson new writers learn easily, and it may be because most of the poetry you’ve read in previous courses is by writers who are long dead and who write, however universally, about archaic (old) matters. In many high schools, students read Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est.” It’s a great poem, but it’s about gas warfare in World War I, not a subject that is too close to home for many students.

So though we always encourage young writers to read the “classics” of literature, it is equally important to read writers who are living today and breathing the same air you are. That’s why, with some exceptions, most of the poems in this book will be by contemporary poets. These writers often take current events and places and turn them into the stuff of poetry. The next section of this chapter contains a bunch of poems that do just that.

In this poem, Kay draws from her own experience teaching at an international school in Jakarta, Indonesia during a terrorist attacks in January 2016. This moment leads the speaker to reflect on the 9/11 attacks and the shift she has made from student to teacher over those 15 years.

The poem might be best described as a prose poem. While it is formatted more like an essay and not broken into particular lines, it is driven by an attention on poetic techniques like simile (“they float up from their seats like tiny ghosts”), surprising language (“the sky outside the classroom is so terribly blue”) that echoes earlier images (“what is an adult if not a terrified thing,” the terror attack, and “blue skies as a sight they love”), and the breathlessness of the whole poem strung together with 34 ampersands. (If you want to play around a little, adjust the size of the browser window while you are reading the poem and see how the lines break differently.)

The first part of the poem (“After Hanif Abdurrraqib & Frank O’Hara”) is the way poets give credit for inspiration. In some ways, it’s the poetic form of an in-text citation. Kay writes about this poem: “When I got home, I read ‘USAvCuba’ by Hanif Abdurraqib and ‘The Day Lady Died’ by Frank O’Hara, and those two poems gave me the keys to unlock this one.” Take a look at these two poems and you can see how Kay uses some of the structures and ideas from them to craft her own response to a more personal experience.

Practice Writing Assignment #1.6 Inspiration

Pick something that you find beautifully made—a movie, a song, a poem, a building, a cell phone. Write a short poem that starts with “After [the thing you picked].” Then write 8-10 lines that tries to use some of the structures or ideas to craft your response.

In this next poem, Carolyn Forché gives voice to a refugee from the civil war in Syria. In the introduction to the audio version, Forché says that her poem was inspired by a conversation with a cab driver who fled his war-torn country.

The poem not only captures some of horrors of the refugee experience (“we fetched a child, not ours, from the sea, drifting face-/down in a life vest, its eyes taken by fish or the birds above us”), but it also makes the connection between the boat carrying the “thirty-one souls” and the taxi carrying the poet and the driver and the poem transporting the reader and the poet and refugee. The speaker’s and the taxi driver’s voice almost seem to merge at the end: “I will see that you arrive safely, my friend, I will get you there.”

In addition to handling weighty subjects, Forché has a way with sounds. Notice the first two lines: The repetition of s-sounds in “grey-sick of sea” and the f-sounds in “falling in our filth” both give the feeling of the small boat on the open sea. She also plays on the sounds and images of “leaflet” and “leave yes” in the line “After that, Aleppo went up in smoke, and Raqqa came under a rain/of leaflets warning everyone to go. Leave, yes, but go where?” The taxi cab driver sees the texts falling from the sky, but those words don’t offer any real direction.

Both of the poems we’ve just read, “The Boatman” and “Jakarta, January” are topical: that is, they refer to current events (or, at least, events that were current when the poems were written). These current events are the core of each poem, the skeleton we talked about when we criticized “maelstrom” for not having one. You can’t say “The Boatman” is about a high school romance, or “Jakarta, January” concerns the death of a beloved pet. These poems simply do not mean anything the reader wants them to. That’s real poetry.

Here’s a third. This one is written by Toi Derricotte, an award-winning poet originally from Michigan. Her poems have been described as “deceptively simple… deadly accurate” by fellow poet Marilyn Hacker. This poem starts with a clear image of black ants carrying their dead back to the ant hill where they will be eaten. It then pivots to an image of the speaker’s husband clearing the grass from his dead father’s gravestone.

Notice how Derricotte uses the line breaks in this poem. If we could hear Derricotte read this poem aloud, we wouldn’t hear her taking long pauses at the end of each line. Instead, the lines run through the breaks. This is called enjambment, and it creates a little tension between what the eye sees and the ear hears. One way to see how this affects the poem is to copy it over and place the line breaks at end punctuation. It is always a little surprising to see how these subtle shifts influences our emphasis and awareness.

Well. Three poems, all by masters of the craft, all with concrete images, all a little difficult for beginners to decipher perhaps, but all with profound messages that cannot be mistaken for toilet bowls.

But death! death! death! Don’t poets write about anything else?

As a civilization, we tend to memorialize places where great battles took place: Bunker Hill, Gettysburg, Shiloh. Lots of death. Here’s William Stafford inventing an “Un-National Monument” to celebrate a place where no battle took place. Stafford died in 1993, but we keep returning to his poetry because we admire the apparent ease and honesty of his language (but we know that he worked hard at it.)

by William Stafford

A great idea here. Stafford inverts the usual concept of the monument, then drives the point home with great phrases such as “hallowed by neglect,” suggesting that this field is ironically made holy for the very reason that people have ignored it–more often, a holy place (Jerusalem, for example) is fought over, sometimes for centuries.

Practice Writing Assignment #1.7 Inversion

Take a couple of clichés or common sayings and then switch them up in a surprising way. Then build a poem around one of those inverted lines. For instance, if you start with something like “read between the lines,” you might adapt that to “read between the lies.”

Here are two more poems about memory. First up is one from David Wright, who teaches writing at Monmouth College in Illinois. “O Dead Man of Goodwill” explores the big ideas of memory and permanence, but he doesn’t focus on big, history-making events; rather, he lingers on the small details of a purchase at a thrift shop.

Your coat smells of cinnamon

and your ties were all silk.I am your shoulders and your

pockets are mine. I boughtalso a scallop-edged green

goblet that may have beenin your mouth. At the store, I left

your felt gray hat, but still feltyour wife’s delicate ghost-hand

in this glove I found (my handsare quite small) tucked into

the sleeve of our coatwhich I wear in the 12 degree cold

to walk and hear the choir:“Whoever are earth-born, together

rich and poor.” The candlesand chalice, the incense fails

to cover over the residual livesI’ve put on and cannot shed,

old coat, your perfumesand the seasons of our skin.

Notice how Wright provides the “things” that William Carlos Williams mentioned: the coat that smells of cinnamon, the scalloped-edged green goblet, the 12 degree cold. It is through these things that he is able to explore the “ideas” of memory and permanence. The other thing we like about this poem is the use of eye rhyme–that is, words that look like they should sound the same but don’t: “green” and “been,” (although there are some places where people say these the same) and “left” and “felt,” which have the same shape and the same letters.

Next, here’s a poem by Darcy L. Brandel. This poem was originally published in a journal called Driftwood Press, which often pairs a poem with an interview with the writer. This allows us a fascinating window into the genesis and process of her piece.

Dreamscape: Sherlock

I mostly remember his body, gaunt

like an ambitious runway model hungry

for something intangiblean awkward cavity, where

his shoulder and neck should have

cradled my head but the bones

felt like shelves I could not reachwhere could I put my desire? how to

organize it or place it appropriately

when his frailty slapped me in the face

and laughed cruelly at my longingwhat a surprise to find him so hollow

beneath that stunning overcoat

a withered frame hidden by heroismdear reader, please be careful:

frail is not the same as vulnerable

and vulnerability, as you probably know

too easily fuels desireno: he was frail.

In the question and answer interview, Brandel writes, “I’m a big fan of the new Sherlock series with Benedict Cumberbatch. I love the brilliantly awkward and aloof sexiness he brings to the character. I’m interested in the complexity of desire and how desire is cultivated, how Cumberbatch’s Sherlock is both an asshole and a savior, a drug addict and a genius, an utter failure and a superhero.” When describing her process, Brandel gives hope to those of us who labor over each word–if we are open to it, sometimes ideas will come to us more easily: “I typically write poems very slowly. I plod, wring my hands, debate word choice for hours. This poem, though, came right out.”

We don’t always get the backstory of a poem, but notice that you don’t need to know that Brandel is a fan of that television show to know what the poem is about. But also see how important the title of the poem is. Without it, we would be a little lost. The title anchors the poem on a particular character (Sherlock) that then allows the poet to explore the contradictory elements within that character.

Practice Writing Assignment #1.8 Line breaks [In-class]

Take one of the poems from above and play around with the line breaks. Can you make the poem do something different by changing where the lines end?

As a student writer standing on the shoulders of thousands of years of great writers, one question that may pop up is, “How in the world can I possibly write something original?” The answer should be fairly evident in the poems presented in this chapter. Don’t rely on the mythologies of the past for your poetic efforts. Write about the here and now of the the world. Sure, you can write a poem that has a Garden of Eden motif, and many contemporary writers allude to Biblical writings, or ancient Greek myths, or other archaic literature. You can also make reference to the latest Netflix show or a tweet from the President. But when you do, keep the poem grounded in your own here and now.

Additionally, two thousand years ago there were no trains or airplanes. And as recently as fifty years ago there were no ATMs, barcodes, or microwave ovens. Twenty-five years ago there were no iPhones, self-driving cars, or cryptocurrency. And even the past few years have brought us a host of pandemics, AirPods, and Candy Crush. The world is changing all the time, and your work can reflect this newness.

Because we began with a group of negative rules, we’ll conclude with some positive ones regarding the art of writing poetry. This list, “Attributes of Poetry,” comes from an anthology entitled Poetry by Jill P. Baumgaertner.

A good poem has the following attributes:

- Precise language that is specific rather than general

- No redundancy or wordiness

- Concrete imagery with sparing use of abstract words

- Appropriate diction that is not pretentious or archaic

- Fresh expression and the absence of clichés

- Appropriate, clear metaphors

- Rhythm and rhyme that do no wrench the rest of the poem to fit an imposed pattern

- Avoidance of sentimentality

- Something new to communicate

“Large Hand of a Pianist (Grande main de pianiste)” by Auguste Rodin is licensed under CC BY 3.0

By now you may be wondering why the chapter title suggests that this is a hands-on introduction to poetry. After all, “hands-on” implies that you get right down to business and work your way along, learning by doing. Well, we’ve tried to do a little of that with you, but, in this case, the “hands-on” is more of a pun that refers to your first poetry assignment.

We call the assignment “Hand Poem,” and that’s just what it is. You are going to write a poem about your hand. The exercise actually comes from the poet Sharon Olds, who presents it on film in a poetry series that was hosted by Bill Moyers on PBS several years back. The first video in that series, entitled “The Simple Acts of Life,” is an amazing introduction to poetry. The video contains Olds and several others reading some of the poems that appear in this book.

Olds directed this exercise at a poetry retreat in New Jersey. Her students sat under a tree with her on an early spring day, and first, she asked them to write down twelve words: four nouns (persons, places, things), four adjectives (descriptive words), and four verbs (action words). There are no rules here: any twelve words, as wild or tame as the writer wishes, will do. Then she instructed her students to write, using as many or as few of the words as they wish, a poem about their hand, seeing as, she said, “we all brought one.” And that’s the assignment. In case you’re one of those who likes rules spelled out clearly, here they are:

Practice Writing Assignment #1.9 First Draft of Hand Poem

Following the directions below, spend 20 minutes generating a first draft of the poem. After 20 minutes, upload what you have to Moodle.

Directions: The guidelines for your first poetic effort have been set forth by Sharon Olds on the video, The Power of the Word: The Simple Acts of Life.

1. Make a list of 4 nouns, 4 adjectives, and 4 verbs. Make them as ordinary or unusual as you wish.

2. From this list, write a poem in which you describe your hand, using as many or as few of the 12 words as you wish.

3. If the poem takes off on its own and turns into something else, fine. If it remains a poems about your hand, it should probably go beyond simple description unless your descriptive skills are truly remarkable.

Practice Writing Assignment #1.10 Second Draft of Hand Poem

After giving the poem at least 12 hours to breathe, return to it. Using the list of tips below, make some revisions to your poem.

Some initial poetry tips:

· Use only the best words.

· Eliminate vague adjectives: very, pretty, rather, really, good, big, small, etc.

· Eliminate excess prepositional phrases (of my….on a…..over the….)

· Use strong verbs (strut, saunter, stroll, stride, etc. for walk).

· Be vivid; paint pictures and, wherever possible, use images of sight, smell, taste, touch, sound.

· Work with sounds (alliteration, assonance, euphony, etc.)

· Think about the line breaks in the poem (and play with how the poem looks on the page.)

· Avoid clichés like the plague.

· Use language that surprises the reader with newness.

Here’s a sample of a poem that started out as a hand poem by the nonfiction writer Sejal Shah. She wrote this back when she was in high school in response to this assignment.

Grandmother by Sejal Shah

I always looked for the silver crescent

at the base of each of your sepia-stained fingernails.

Hands, sticky-sweet like the jam-filled crepes

you filled my weekend afternoons with.

A shrinking wheel fluked by red, raw spires;

glowering knuckles line with lyre string,

gyrating to smooth the dough.

You were my Sundays

and you swallowed my life.

Sometimes

I still feel your wrinklefloured hand

brush across my forehead,

prematurely whitening my eyebrows

so that briefly they match yours and

your face is once more reflected in mine.

ASSIGNMENT # 1.11: FINAL DRAFT HAND POEM

Turn in your third draft poem

A collection of poetry definitions

Poetry is…

…not the language we live in. It’s not the language of our day-to-day errand-running and obligation-fulfilling, not the language with which we are asked to justify ourselves to the outside world. It certainly isn’t the language to which commercial value has been assigned. (Tracy K. Smith)

…a revelation in words by means of the words. (Wallace Stevens)

…more a threshold than a path. (Seamus Heaney)

…ordinary language raised to the nth power. Poetry is boned with ideas, nerved and blooded with emotions, all held together by the delicate, tough skin of words. (Paul Engle)

…language at its most distilled and most powerful. (Rita Dove)

…the art of creating imaginary gardens with real toads. (Marianne Moore)

…the clear expression of mixed feelings. (W.H. Auden)

…voice music (Erica Jong)

If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me, I know that it is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that it is poetry. (Emily Dickinso

Media Attributions

- sea-outdoor-rock-silhouette-person-mountain-697531-pxhere.com is licensed under a Public Domain license

- skeleton