4

Sounds Make Sense

As you may have seen in chapter one, a definition of poetry offered by poet Erica Jong is “voice music.” Galway Kinnell has said, “Poetry is the singing of what it is to be on our planet.” A major part of the craft of writing poetry is using sounds to convey meaning. As the chapter title suggests, sounds make meaning in poetry.

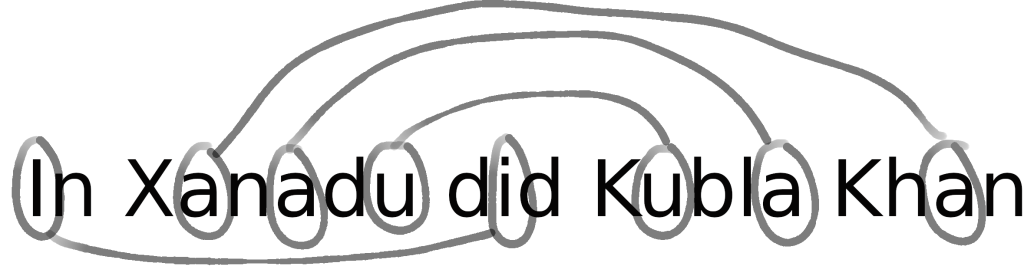

Let’s begin by contrasting two famous opening lines of poetry, one of which creates pleasant sounds or euphony and the second of which creates harsh, unpleasant sounds or cacophony. The first line is the beginning of “Kubla Khan” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, a Romantic poet of the early 19th century and a contemporary of Blake and Keats, whose work we have seen in previous chapters. The poem begins by telling how the great Asian emperor ordered the creation of a pleasure dome, or fun palace, we suppose:

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure dome decree

Where Alph the sacred river ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

To suggest the pleasures of the palace, Coleridge attempts here to create euphony, the beautiful, rhythmic “music” of poetry. There’s a lot of alliteration (”Kubla Khan,” “dome decree,” “sunless sea,” “river ran”) and some nice entwined rhyme (abaab). But it is the first line of the poem that is a true masterpiece of euphony, and the key to this is to be found in assonance, or repeated vowel sounds. Let’s look again, highlighting the assonance via our pen:

The point of this mess is that every vowel in the first line can be paired up with a similarly sounding vowel (some people have to stretch for “Xan” and “Khan,” but it’s there.) This is true craft and certainly not just blind luck! This is what it means to be a poet.

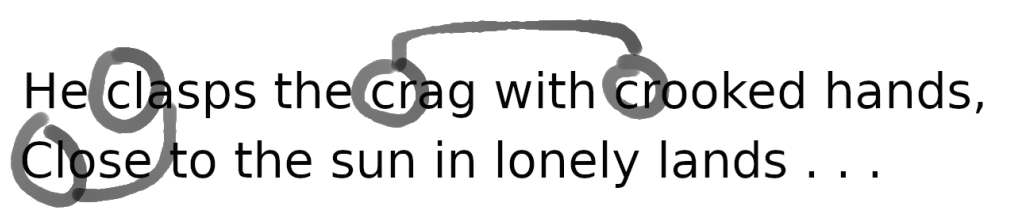

Now let’s look at a similar attempt to created cacophony in Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem “The Eagle,” which we showed you in chapter 2. Here, again, is the beginning of that poem:

He clasps the crag with crooked hands,

Close to the sun in lonely lands . . .

The repeated “cl” and “cr” sounds are harsh, grating, and contrast dramatically with the euphony of “lonely lands” at the end of line 2. This is to characterize the eagle itself, which is a tough, kingly, powerful bird in an aery world of mountain rocks and jagged peaks. But again, let’s look even more deeply at Tennyson’s craft. If you circle the “cr” and “cl” sounds, you get:

Look at the symmetry of a “cl” followed by two “cr”s closed by a final “cl.” Craft or just blind luck? Are you beginning to sense which? Let’s go further still. Tennyson could have made the first line absolutely, one-hundred per cent symmetrical if he’d only used the obvious word at the end of line one: “claws.” After all, eagles don’t have hands, do they? (rhetorical question!) So why did he choose “hands”, then delay the “cl” sound one word to the next line with “close?” If you remember the poem from chapter 2, Tennyson is attempting to personify the bird to highlight its nobility. Using “hands,” a human attribute, calls attention to the bird’s lofty position in the avian world (it’s the “king” of birds) all the more so because we as audience expect the word “claws,” due to both the symmetrical, harsh music of the poem’s opening and to good, old common sense about bird physiology. Writers often use the method of expectation and surprise. Tennyson’s opening is a perfect example.

If you have been reading this book with reasonable attention, you may have noticed examples of both euphony and cacophony in previous poems. Wallace Stevens’ blackbird “sits in the cedar limbs” at poem’s end, a beautiful euphonic conclusion.

From the above, we hope it is clear to you that poets purposely use sounds to create meaning, and that various sounds can imply or connote ideas. You don’t have to be an expert in linguistics to be a fair poet, but it does help to know your sounds well. By way of analogy, if you are going to become an artist who paints people, it is tremendously helpful to study anatomy. Knowing the structure of the human body, the bones, muscles, ligaments, etc. that lie under the skin, allows the painter to depict more accurately the surface features. Interestingly, comic book artists, who draw those super heroes with bulging biceps, contorted faces and the rest, need to be acutely aware of the structure of human physique.

So too, a poet must know sounds. We do not pretend to be linguists, nor to give you a complete picture here. Our purpose is to introduce you to how sounds make sense and how poets make meaning in this manner.

We break sounds into consonants and vowels. You should already know from previous study in English that alliteration is the repetition of initial consonant sounds (big, bad); that consonance is the repetition of internal consonant sounds (juggle, wiggle); and that assonance is the repetition of internal vowel sounds (dim, wit). Such techniques tend to highlight important words by calling the reader’s attention to them and by repeating sounds that the poet wants to stress.

We’ll begin with consonants. When you create alliteration and/or consonance with any of these types of sounds, you produce an effect.

Consonants such as “m,” “n,” and the final sound “ng” are called nasals, because the nasal passages are open when we make these sounds. They can create a feeling of sadness or melancholy, like a minor chord in music, when they are repeated. They can also be euphonic. A classic example is from our Eagle man Alfred, Lord Tennyson, in a long poem called The Princess: “The moan of doves in immemorial elms,/ And murmuring of innumerable bees,” he writes.

“L”s and “r”s are called liquids. They flow along beautifully, easily, and create a feeling of lightness. There’s even an old Sesame Street routine based on the euphonic qualities of the letter “l.” Ernie tells Bert how “lovely” and “lilting” the sounds of “l” words can be, and Bert, who’s a little slow, chimes in with supposedly beautiful worlds such as “light bulb” and “linoleum.”

Here’s Edgar Allan Poe, who argued that the primary purpose of poetry was “the rhythmical creation of beauty,” creating just that with liquid sounds, among other devices:

If I could dwell

Where Israfel

Hath dwelt, and he where I,

He might not sing so wildly well

A mortal melody,

While a bolder note than this might swell

From my lyre with the sky.

Abrupt consonants such a “b,” “p,” “g,” “k,” “d,” and “t” are called stops, where the air literally stops at the opening to your mouth as you say the sound. These sounds slow down the action, make the lines read in a more staccato or herky-jerky fashion. “The bumbling, big, brown bear,” is a bit overdone, but you get the picture.

Fricatives buzz. “F,” “v,” “s,” and “z” constrict the air flowing through the mouth, but unlike stops, the air continues past the mouth. Here’s D. H. Lawrence, doing the obvious in his poem “Snake”: “He sipped with his straight mouth/Softly drank through his straight gums, into his slack long body,/ Silently.” You didn’t expect “b” or “k” sounds to mimic the hissing, slithering reptile, did you?

Semivowels or glides such as “w,” “h,” and “y” produce a lot of air that flows out past your mouth. In his “Ode to the West Wind,” Percy Bysshe Shelley creates the sound of the wind in the opening lines: “Oh wild west wind/Thou breath of autumn’s being.” Very windy, indeed.

Vowels are also categorized by linguists. For our purposes, it is important to distinguish between those sounded in the front of the mouth that have a higher, shriller pitch (”i” in “pit,” “a” in “hat,” “e” in “pet”) and those sound in the back of the mouth, which take longer to say and which, for this reason, slow the pace down (”o” as in “boat,” “a” as in “late,” “e” as in “pea.”) Notice how Shelley uses long vowels to enhance the sound of the wind above.

There is beautiful music in assonance (did you catch “beau-” and “mu-” there?).

When techniques of assonance, alliteration and consonance are combined, poets work musical wonders. Here are some:

Like a fading piece of cloth

I am a failure

No longer do I cover tables filled with food and laughter

My seams are frayed my hems falling my strength no longer able

To hold the hot and cold–Nikki Giovanni, “Quilts”

You turn the kitchen

tap’s metallic stream

into tropical drink,

extra sugar whirlpooling

to the pitcher-bottom

like gypsum sand.–Marcus Jackson, “Ode to Kool-Aid”

From socks to shirts

the selves we shed

lift off the line

as if they own

a life apart

from the one we offer.–Ruth Moose, “Laundry”

Down valley a smoke haze

Three days heat, after five days rain

Pitch glows on the fir-cones

Across rocks and meadows

Swarms of new flies.–Gary Snyder, “Mid-August at Sourdough Mountain Lookout”

I’m going to wrinkle this word,

I’m going to twist it,

yes, it

is too smooth,

as if a large dog or a large lake

had passed its tongue or water over it, over it,

for years. Years.–Pablo Neruda (tr. Kudinoff & Young), “Verb”

[…]And us–we–

stood inside the storm

like the whale

The well carried the ill

till none was well–Kevin Young, “Catechism” from Ardency: A Chronicle of the Amistad Rebels

Onomatopoeia is the technique in which these sounds are most clearly used to enhance meaning. An onomatopoeic word sounds like what it is.

“Bang” uses the hard “b” and “g” and the short “a” to created a harsh noise.

“Whisper” uses the semivowel “w,” the softly buzzing “s,” and the liquid “r” to flow like the sotto voce technique it describes.

In this light, consider “buzz,” “clang,” “howl,” “bark,” “crash,” and numerous others.

Rhyme, which includes many forms, had been out of fashion in twentieth-century writing despite Robert Frost’s witty observation that writing poetry without rhyme is like playing tennis with the net down. But in the centuries before pen, paper and Gutenberg, a main function of rhyme was mnemonic, or as a memory device. Think about it. You probably have memorized the words to a number of your favorite songs. The melody and rhyme and, of course, repetition of the song on the air waves and on your playlist makes it fairly easy to memorize without even trying that hard. You probably even know the words to some songs you don’t like but have heard a million times: rhyme and repetition can be a pretty strong combination.

Over the centuries, with advances such as pen and paper, movable type, laptop computers, Google, wikipedia, etc. it’s not as important to memorize anything anymore, and rhyme has been more associated with light verse and television commercial songs (“jingles”) than with serious imaginative literature. In criticizing Edgar Allen Poe’s penchant for internal and external rhyme, 19th-century poet and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson actually anticipated this trend when he dubbed Poe “The Jingle Man.”

But literary movements are often cyclical: what goes around comes around. Compare what happened in art after the invention of photography in the 19th century. Movements such as impressionism, Fauvism, cubism, dada, expressionism, surrealism and abstract expressionism led to more and more abstract works, or what we call non-representational art (work that does not depict actual things we can identify). Non-representational paintings were all the rage until a swing back to representation has become evident in the work of many painters.

So too, rhyme is back in favor among some poets, often associated with the “new formalist” school. But it is rhyme with a twist. The heavy, “jingly” type of rhyme of the past is still not completely acceptable, except in rare, sometimes comic, instances. More preferable to contemporary poets is off-rhyme, or consonance, sometimes combined with a few exact rhymes here and there. This is not to say that poets haven’t used off-rhyme for centuries to soften the effect produced by other lines that rhyme exactly, or even to skew things just a bit to suggest that the world doesn’t always rhyme. Look at how, in 1890, Emily Dickinson begins with exact rhyme in this powerful poem about isolation and forced loneliness, then moves to off-rhyme in subsequent stanzas:

The Soul selects her own Society–

Then–shuts the Door–

To her divine Majority–

Present no more–Unmoved–she notes the Chariots–pausing–

At her low Gate–

Unmoved–an Emperor be kneeling

Upon her Mat–I’ve known her–from an ample nation–

Choose one–

Then–close the Valves of her attention–

Like Stone–

As an aside notice two things:

- This is the only poem (except for haiku) that we’ve included so far without a title, and

- Dickinson closes on the word “Stone” which leaves that word, with its strong open “o” vowel sound ringing in the reader’s ear to suggest the finality of the persona’s decision to isolate herself. The technique is similar to holding a note on a musical instrument after the song ends.

Take a look at Terrance Hayes’ poem, “American Sonnet for My Past and Future Assassin [“Inside me is a black-eyed animal”]”. He is playing around with the form of the classic sonnet by creating an American version (instead of the Italian or Shakespearean styles). Note the ways that he creates echoes of rhymes in some of the lines with assonance, consonance, and alliteration: animal/shell and bird/black. And then he follows these pairs up with the word “held,” which pulls together the el-sound of “shell” and the d-sound of “bird.”

We also like this poem because it contains the line “a thousand black/Birds whipping in a storm” that reminds us of the Wallace Stevens’ poem that gave us the title of our book. It also reminds some readers of one of best Irish writers of the 20th century, W.B. Yeats. In Yeats’ poem “Easter, 1916” he writers about the turbulent times surrounding the Easter Uprising in Ireland. Hayes is also writing about challenging times and uses a similar images and oppositions. But like all great poets, Hayes creates a poem that is original and surprising even when he plays with the echoes of the past.

Finally, we’ll give you a few complete poems that are heavily dependent upon their sounds. We would recommend that you read them once just to hear the sounds, and then examine them to see how these poets created the sounds. You could even print some of them out and annotate them by circling the letters and words like we did at the top of this chapter.

This first poem builds off a report of discovery of “hobbitt-like” human remains in Flores, Indonesia. We love how Smith, a former U.S. Poet Laureate, takes the scientific article and turns it into something magical.

Next, we can’t help but share with you Anne Waldman’s “Maelstrom: One Drop Makes the Whole World Kin.” Let’s just say we have a soft spot for maelstrom poems.

In Robert Haas’ poem explores what is said and what isn’t said. Notice all of the references to things right at the end of World War II and all of the horrors of that conflict.

Hong’s poem sets up a challenge of only using words that contain the letter “a.” Notice all of the different sounds these letters can make.

A word about using sounds in your own writing, whether in poetry or prose. The tendency for novices is to use new knowledge indiscriminately, that is, without real purpose or direction. When you employ sound devices, you should not just put in a bunch of them to impress your readers that you know what alliteration, assonance and the rest are. You need to use them to produce a desired effect.

A Sounds Make Sense Poetry Writing Exercise

In the past few decades, slam poetry has taken its place as a legitimate genre of poetry. While reciting poetry is as old as poetry itself, slam poetry tries to shatter the stuffy poetry reading through competition, performance, and audience response. This newer format creates poems that are meant to be heard, and because they live more easily in performance than on the page, they usually take advantage of a wide-range of sound devices. To give you a quick introduction, take a look at the following examples–all videos of live performances of the poems. After to watch these ten examples, we’ll take a look at Joshua Bennett’s “Tamara’s Opus” a little more in-depth to see how he makes sense with sounds. But first, a playlist of poems:

Marshall Davis Jones, “Touchscreen”

So now, we’ll give you your next poetry assignment.

Exercises

Assignment # 4.0: What The _______ Said

1. Write a poem called “What the ________ Said,” modeled on Mona Van Duyn’s “What the Motorcycle Said.” Your piece would probably work best if you choose, as does Van Duyn , an inanimate object that makes particularly distinctive sounds. Various animals, however, will probably work.

2. Unless you’ve thought of a topic right away, begin by brainstorming a list of a several objects that you might want to write about. From this list, choose the one that:

a) seems most intriguing to you

b) has the most interesting sounds ( make sure you can put them on paper!)

c) will generate the best poem

3. Next , start a new brainstorming list by writing your topic on the top of a piece of paper. Then think of every sound you can that is associated with this object and write them underneath. Really rack your brain for every sound you can think of. Ask friends or parents what sounds they think your object makes. Remember, in this poem, sounds are the key. Make your object sing out! Be clever. Be creative. Go wild (within reason!).

4. When beginning your poem, make sure you stick to writing what the object says, not what a person talking about the object says. Many students who do this assignment become confused and have a person speak about the object. While this may work, notice how Van Duyn personifies the motorcycle in her poem by having it speak.

5. Notice Van Duyn’s refrain, “That’s what the motorcycle said.” It works very well both times she uses it to remind us of the speaker. You may want to use a similar refrain: “That’s what the ________ said.”

6. Be sure to characterize your object from as many angles as you can. Notice how Van Duyn shows her motorcycle moving, moving, moving “Passed . . . passed . . . passed.” Give your poem a plot if you wish. Make things happen. Show your object performing actions.

7. The very best poems will go beyond simple explorations of sound to include a theme. Note how Van Duyn suggests the joys of speed and

freedom. Notice, beyond this, how she suggests the ironies behind the

motorcycle’s rebellion.

Tips and Samples:

Actual topics have included, “What the toaster , ocean, sixth string (of a guitar), toilet (yes, however scatological), cat, ice storm, said. Number seven on the above sheet is obviously a bit harder than the rest, but remember that the whole idea of using sounds is to make sense. Your use of alliteration, assonance, rhyme, whatever, should spill over into the meaning of your poem. A famous quotation by the late University of Toronto professor Marshall McLuhan suggests that “The medium is the message.” McLuhan meant that how you say something is what it means. Consider this concept in your creation of sounds.

Media Attributions

- 46090

- kubla khan

- tennyson