Revision means what it looks like: RE-vision, to see again.

So great, you’re thinking. That sounds easy.

Well… it’s not. (Surprise!) Revision requires us to look at our own work again with fresh eyes. That’s tricky for a number of reasons:

- Maybe you poured your heart and soul into your paper, spending hours crafting each beautiful sentence about a treasured memory. If so, it’s going to be hard to go back and tear into that work. You might already think it’s got nothing left to change, and every fix might feel like running a stake through your heart.

- Maybe you threw together a draft the night before the rough draft deadline, and when you look at it again, you can’t even remember what you were thinking. You’d rather throw the whole thing out and start again then try to fix the paper up. Revision is going to feel like swimming with weights on your legs.

- Maybe you’ve tried to read and look for mistakes before, only to have nothing really jump out at you. Yet later, when you get the paper back with a grade, there are obvious mistakes all over. Revision can seem pointless or frightening if you’ve had that experience.

If your past experience with revision has been negative — or you have no experience with revision at all — then take a moment to consider why. What is it you don’t like about this experience? Why might you have avoided it in the past?

You’ll likely be asked to reflect on these questions after major writing assignments, so take some time to think about them now.

Reasons We Hate Revision: It’s Time Consuming

“I have rewritten — often several times — every word I have ever published. My pencils outlast their erasers.” — Vladimir Nabokov, Speak, Memory, 1966

Many writers despise the process of revision because it’s the most work-intensive piece of the process. It is painful and painstaking. In college, perhaps the most annoying part of the revision process is that it takes time.

If you’ve been in college for more than a day, you’ve figured out that everything takes time, from finding your classrooms or remembering your log-in names and passwords to reading your textbooks. Writing your papers takes time. Understanding your readings takes time. Meeting with your teachers takes time. Going to class takes time. Waiting in line at the bookstore takes time. You get it. You’re there.

In the middle of all of this, many instructors ask you to produce writing on a short timetable: sometimes, an essay will be assigned and due within two weeks. Sometimes, a paragraph is due by the next class period. Where, then, will we find time for revision?

The only way to find time is to make time: good writing requires planning ahead.

Whenever possible, build one extra day into your writing schedule. If you have a paper due next Thursday, plan to finish it no later than Tuesday night; then, reserve time — even if it’s just thirty minutes — on Wednesday to re-read the paper and revise. Of course, having more time will be better. The longer the gap between writing and revising that you can reserve, the stronger your abilities as an editor will be.

So — do you have time to revise? Sure. If we think of revision as something that’s extra, on top of the assignment, then it’s easy to leave it off. Think of it instead as part of the assignment. You’re required to write not just any paper, but a good, final draft; that means you are expected to revise every college paper before you turn it in.

Writing classes that require a first draft due date — whether for peer revision or instructor review — have this revision schedule built in, but most assignments, whether for class or work, will not be so kind. Building a habit of revision in college, where you’re expected to be spending hours each week on your classwork, will help you when you leave college and no longer have that “study time” written down on your schedule.

Reasons We Hate Revision: It’s Too Hard

As we talked about when discussing peer revision, it’s difficult to think critically about our own work. Sometimes, it’s hard to find things wrong because our work is in our own voice, filled with our own thoughts, and makes perfect sense to us. Sometimes, it’s hard to find things right with our own work because we’ve been convinced that we’re not good writers — or we feel that this particular paper isn’t good.

However, remember that you’re not the whole audience for what you’re writing — which means that your judgment, while still the most important in many ways, isn’t the final judgment.

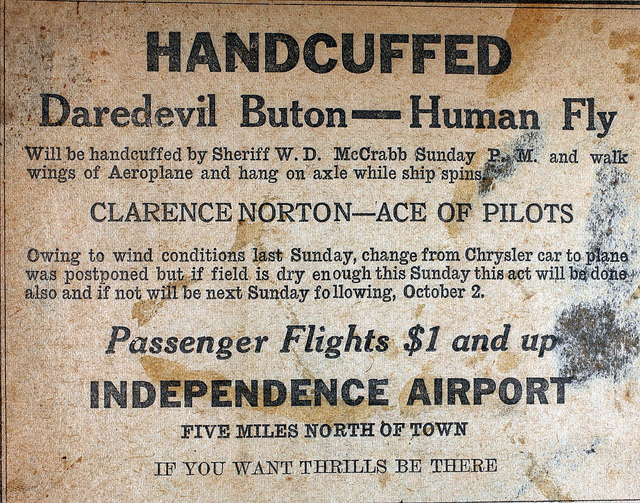

Take, for instance, this flyer, used to advertise a flight show. It was likely written by either a friend of the performer or someone who stood to make money from his performance. Therefore, that writer probably knew most of the information — time, date, location, names — by heart. In fact, it may have been Daredevil Buton himself who wrote this ad. This has clearly been revised — it mentions that last week’s show had to be canceled due to wind. That correction, you’ll see, is very small — the sign is trying to lure people in with its daring promises.

Revising our work requires us to pretend to be the person reading the flyer, not the person who’s being talked about. In his everyday life, it’s hard to believe that Mr. Buton introduced himself as Human Fly; yet here, he had to add that in to draw attention.

This is exactly what we need to do in revision. Pretend you’re an outsider. You’re just looking at the paper to hear a story, learn a lesson, figure out what a reading means. What do you find to admire? What gaps do you need to fill in?

Ask yourself: What would my instructor say while reading this? What would my classmate still need to know?

This is why time is so important for the revision process. When you read a paper you’ve just finished writing, your brain will fill in pieces that aren’t on the paper. The further away from the paper you can move, the better your ability to read it with distance.

Reasons We Hate Revision: The Results Are Disappointing

“I don’t write easily or rapidly. My first draft usually has only a few elements worth keeping. I have to find what those are and build from them and throw out what doesn’t work, or what simply is not alive.” — Susan Sontag

Some of us don’t like revising because we’ve tried it before and had less than stellar results. Students often say they don’t revise because they feel they don’t catch the right details, or they don’t revise because they don’t know where to start. Both of these are challenging situations, and both of them can be fixed by taking up a structured way of revision. The next few pages will introduce a way of thinking about revision that should help you efficiently attack any paper or piece of writing and garner some useful results.

However, it’s important to remember that the goal of revision isn’t perfection. No piece of writing is perfect. Even one that you love, a favorite from childhood or a recent inspiration, has flaws. Maybe the writer wishes they could do it again; maybe some audiences find the piece boring, too long or too short, offensive, unfunny, or otherwise bad. No piece of writing is perfect, and certainly no piece of writing produced under a high-pressure deadline is expected to be flawless.

Revision means re-seeing. Seeing again lets us improve our work; it doesn’t guarantee everything will be fixed. Just because you revise doesn’t mean you’ll get an A on every paper. It does mean that every paper will be better than it started, and that you’ll be a better writer at the end of every paper, and that’s our goal.