Overview

This reading will explain the value of the prewriting process in creating a usable, college-level draft of an assigned piece of writing. We’ll discuss Assignment Analysis (Writing Situation), Idea Generation, Outlining Strategies, and Drafting.

To complete this reading, you’ll need to set aside time to complete the exercises assigned on paper or on a computer. Some exercises require you to time yourself at an activity, so having a clock or timer nearby will also be useful. You’ll be asked to briefly report your experiences at the end.

Assignment Analysis: Review

In your last reading, you discovered how to analyze a given assignment. Different textbooks and instructors have different names for this. It is sometimes also called Analyzing the Rhetorical Situation or Finding the Writing Situation. These all mean the same thing, and they all ask you to do the following:

- Create a Question to work with

- Fully comprehend all parts of the assignment

- Determine your audience (primary and secondary)

- Determine the purpose of the assignment

- Narrow or broaden your topic to fit the requirements

- Fully understand formatting, research, length, and time requirements

Once you’ve completed this, you’re ready to move into the most important stage of the entire writing process: Idea Generation.

Idea Generation

Where do good ideas come from? Well, for most of us, the best ideas we’ve come up with come from existing interests. If you have little interest in writing, then it’s hard to come up with what to write about.

Sometimes, the problem is the opposite thing: Given a prompt, we can come up with too many things to talk about. Having too little or too much to write about can be difficult, and the process of generating useful ideas will help you with either of these.

To begin generating ideas for an assignment, we need to work with the question that we created in our Assignment Analysis.

Let’s look at a typical College Writing prompt to get started. This is a question taken from an in-class final exam given to Writing 121 students a few years ago:

Describe one gift that you have. Reflect on how you have used that gift to make the world a better place.

A student taking the exam generated the following question from this prompt:

What personal gift have I used to improve the world, and how have I used it?

Now, some students will just jump right in and start answering that question. There are positives to this approach: certainly, the work gets started more quickly, and sometimes, that first instinct is the best guide. However, there are some downsides, too: Writing the first thing that comes to mind may lead to more shallow writing instead of the deep reflection that college courses ask for; the first idea one thinks of may not be the best, and it might not fulfill the requirements of the assignment.

So, to avoid these problems, we need to use this question to generate multiple possible ideas to write about, so that we can later narrow down to the best idea.

The methods we’ll discuss for idea generation will be:

- Brainstorming

- Freewriting

- Think Alouds

- Cluster-mapping

- Journaling

Idea Generation: Brainstorming

The most standard and tested ways of moving ideas from your head to your paper are through Brainstorming and Freewriting. These are exercises we use to just get out our ideas. They do not require you to consider grammar, spelling, or content. That means don’t spend even a minute thinking, “Am I doing this right? Is this a dumb idea?” In this level of prewriting, there are no dumb ideas and no bad writing.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is used in academic, business, and social settings all of the time. If you’ve ever just thrown out ideas with friends about where to go for dinner or what movie to see, you’ve been brainstorming. Often, people who learn best through seeing things do well with brainstorming because it allows for list-making and drawing.

In an academic context, we use Focused Brainstorming to help generate useful ideas. The easiest way to brainstorm is the old school way:

- Get out a piece of paper (lined or plain)

- Write the question you’ll be thinking about at the top

- Set a timer for a length of time just beyond your comfort level. Five minutes is a minimum; try for 7 to 10 if you’re generating ideas for a longer work, like a research essay

- Once the timer starts, you can list, draw, connect, write, and illustrate your ideas for the full time. DO NOT stop writing! Don’t pause to keep thinking or stare into space. This is not the time to notice that your floors need to be swept or to start working on your grocery list.

- If you have trouble staying focused during this time, break the time limit down into smaller pieces at first: 3 minutes of brainstorming, followed by a break, followed by 3 more minutes. But don’t let yourself off the hook until you’ve finished the prescribed amount of time!

At the end of your timed session, you’ll probably have a page full of chaotic ideas, lists, doodles, and writing. That’s great! That’s exactly what we’re looking for. If, when the timer stops, you feel like you have more to say, then keep going. Run another timed session. The more the merrier here.

Why are we timing this? Well, one major idea behind brainstorming is that everyone will hit a “blank” after some stretch of time. Sometimes, two minutes in, we run out of steam and find we’re just doodling or repeating the same thing again and again. That’s actually OK; after a minute or so, often, that repetition and perseverance will lead to a completely new idea popping up out of nowhere. That idea is, often, a great idea to work with, and it’s coming from a place in your mind that’s deeper than the “first instinct” answer you may have started with.

The prompt and question that we saw before will be a good place to start practicing. Spend the next 5 minutes trying out brainstorming as a way of generating ideas. To help you time this, see the box below for links to Countdowns online. When the music stops, pencils down!

Examples

Most smartphones include a timer/stopwatch App that you may be able to use. However, on a computer, consider a few other options for timing yourself, as well. You can search for your own favorite type of music, though music without words may be easier to brainstorm by. Here are two examples:

- YouTube: Classical Music 5-minute timer

- YouTube: Electric music 5-minute timer

Exercise: Brainstorming

Question and Prompt

Prompt:

Describe one gift that you have. Reflect on how you have used that gift to make the world a better place.

Question:

What personal gift have I used to improve the world, and how have I used it?

When you’re done, review your brainstorming. Did you come up with ideas you would not have otherwise? Hang on to what you’ve done for now, and we’ll keep working with it as we go.

Idea Generation: Freewriting

Another way to get ideas out of our heads and onto paper is to try freewriting. In fact, many of us already freewrite as a way to get started on a paper, meaning we dive right in and start writing. However, Freewriting offers all the benefits of that “jump right in” strategy with none of the pressure (like worrying about spelling, grammar, and complete sentences).

To complete Focused Freewriting for an academic assignment, do the following:

- Write the question you’re answering at the top of a lined piece of paper.

- Set a timer for just longer than you’re comfortable with. Five minutes is a good minimum to start with.

- Once you’ve started the timer, start writing anything related to the question that comes to mind. Don’t worry about punctuation, spelling, or “getting the right answer.” Just write.

- If you run out of things to say, don’t stop writing. Instead, start asking yourself questions, or repeat phrases you’ve already written down. Stick with it for the full time.

- When the time is up, highlight or underline anything from the freewriting that might be useful in creating an outline or draft.

- If you have more to say, keep going! Set another timer, and write again!

At the end of a freewriting session, you’ll likely have a page of hand-written (or typed) notes that you can begin copying and working with. That’s easier than just starting your paper with a blank page. We’ll look at ways to move from that messy page to a more orderly outline in just a bit.

For now, let’s practice. Load up a 5-minute timer again, and find either a blank piece of paper or a blank document on your computer. The prompt and question in Exercise 1 will be a good place to start.

Remember, this time, focus on writing for the entire time. Brainstorming allows for doodling, bubbles, connections, and drawing; freewriting, what we’re doing right now, means you keep writing words the entire time. Ready?

Exercise: Freewriting

Prompt and question:

Prompt:

Describe one gift that you have. Reflect on how you have used that gift to make the world a better place.

Question:

What personal gift have I used to improve the world, and how have I used it?

When you’re done, compare your brainstorming and freewriting. Do they look basically the same, or did you do more drawing in the brainstorming? Did one feel easier than the other? Did you come up with anything new in the freewriting?

Though these two ideas seem almost the same, they can generate ideas in different ways. One may work for you on this assignment, while the other may generate better ideas on the next one. Sometimes, they’re better in combination: brainstorm to get big ideas (concepts) outlined, and then freewrite about the concepts to narrow your thinking.

Let’s try another way to turn ideas into writing.

Idea Generation: Think Aloud

Sometimes, putting pen to paper is the hardest part. It can feel intimidating to get started with a writing assignment by writing, particularly if writing has caused you anxiety in the past. Of course, there are other ways to get started. Some of us generate our best ideas while we’re completely away from our work — maybe you think best while you’re at the gym or in the shower; maybe you come up with great ideas when you’re mowing the lawn or playing Hungry Hungry Hippos. It’s important to pay attention to the patterns of your own ideas, so that you can begin to duplicate them as assignments come due. We tend to think that the obvious solutions — like just sitting down and thinking — will always work. That’s not always true. Sometimes, a brisk walk, a break, a snack, or a chat with a friend are actually what’s required to get the creative juices flowing.

If brainstorming and freewriting didn’t work well for you on this prompt, don’t worry, and don’t throw them away as useless. They’re tools you can save for the future. They may help you on your next assignment. Keep trying. Train your brain to respond and focus by repeating these exercises even when it’s frustrating. Just like trying to get stronger at the gym, writing and its process requires hard work and repetition to get better.

In the meantime, you can also try to generate ideas by Thinking Aloud. Though the name sounds obvious — you voice your thoughts — the process isn’t quite as simple as yelling out your ideas wherever you are. Think Alouds are best done in pairs or small groups.

- Find a willing friend, classmate, or tutor.

- Offer them the assignment handout, prompt, or other material that explains what you’re working on.

- Then, spend a few minutes talking through ideas with your partner.

- Their focus should be on prompting you to come up with more ideas, not in critiquing the ideas as they come up.

- Ask your partner to write down the ideas that s/he hears from you.

This exercise is particularly useful when you’re trying to be certain you understand an assignment; when you have to explain it to someone else, you’ll find out quickly whether you’re certain about what you’re doing!

Sometimes, it’s not practical to work in a pair. In that case, you can Think Aloud by yourself — forgetting whatever you’ve been told about the problems of talking to yourself.

To generate good writing ideas through a solo Think Aloud, do the following:

- Find a place where you’re comfortable doing an exercise that will require you to talk. (For instance: an office with the door closed, or a closed study room at school).

- Use a dictation web site, phone app, or voice recorder.

- Many smartphones come with a voice recorder installed. For instance, you can ask Siri on an iPhone to write an e-mail for you; many Android phones have Google-enabled dictation, too.

- There’s a free dictation web site at dictation.io that will let you dictate directly to a blank page and then export (send) your text back to yourself. It’s powered by Google.

- You can also purchase Digital Voice Recorders for under $20.

- Set a timer for a minimum of three minutes.

- Place the question you’re trying to answer in front of you on a piece of paper.

- Then, spend the full time trying to think out loud about your topic.

When you’ve finished, you can playback the audio or look at the transcript to see what you’ve generated.

If you decide to try these, great! Save any ideas you generate, and we’ll work with organizing them in the next steps.

Outlining Strategies

The next piece of prewriting we’ll talk about is getting those jumbled, generated ideas organized. The first strategy we can use is one that works both for generating ideas and for organizing them: Creating a Cluster Map. Then, we’ll talk about using outlines, both formal and informal, and about visual organization methods.

Cluster Mapping

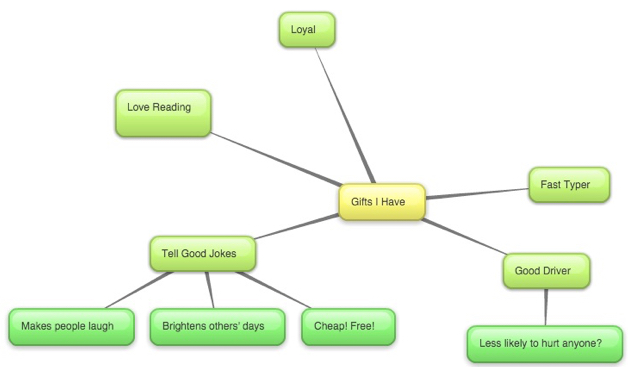

This is a picture of a cluster map completed from the prompt we were working with before. A cluster map has the major idea in the center. It is connected to another layer of bubbles that answer the central question or offer support for the central idea. Each bubble on the second layer may also be connected to more sub-bubbles, which will again provide support to their central idea. By creating a map like this, we can see which ideas are big ideas that need plenty of support and which details are just small pieces of a bigger question.

Cluster maps (also sometimes called Idea Webs or Mind Maps) can be used to generate ideas or to organize them.

To generate ideas by cluster mapping, begin by placing the topic or question in the center. Then, draw lines out to ideas/answers about that topic or question. Underneath and attached to each bubble that holds a possible answer, you can attach more details, facts, supporting points, or other illustrations about that particular idea.

To organize your existing ideas with a cluster map, take your previous prewriting (brainstorming, freewriting, or notes from Thinking Aloud) and try to put the ideas onto a web. You can draw a blank web with the question at the center and then 3 or 4 bubbles attached to it; then fit in ideas you had to those bubbles. The next level of the map is used for details and support, so you can fill those in from your prewriting or begin to come up with further ideas.

Cluster mapping can be done by hand (all you need is paper and pen!), or you can find any number of online sites that allow you to map your ideas. This graphic was done using the free mapping tool at bubbl.us.

One great way to use a cluster map is as a way to decide what topic to write about. If, after drawing a map of your ideas, you see that some have many supporting details, and others have only a few, you can easily choose which would be better to write about. In the above map, it seems more likely that the writer will be able to talk about how Telling Good Jokes helps the world than about how Being a Good Driver is useful.

Clustermapping is just one way of organizing your work.

Before we cross over into organization completely, there’s one step we have to take. After you’ve finished generating ideas but before you organize your information, you must come up with a one-sentence answer to the question you formed during the Assignment Analysis stage. This answer will be the driving force for the rest of your paper. No matter the length of your paper, strive to answer that initial question with just one sentence. Of course, there will be further details to explain — otherwise, why write an entire paper if you can answer the question in just one sentence?

This sentence, the answer to the question of the assignment, will be your Topic Sentence (for a paragraph-length assignment) or your Thesis Statement (for an essay or longer assignment).

Though we’ll talk again about generating good thesis statements, this is really all there is to it: Answer the question being asked in one sentence.

Outlining: Formal vs. Informal Outlines

Many student writers have worked with outlines before. Often, they’re assigned as part of the prewriting process. They can be useful; they can also be an extra hurdle. How and when you use an outline will depend on the kind of writing you’re doing and how organized you feel about your material. Creating an outline is an important skill that most writers use in some form, whether informally or formally.

Formal Outlines

Formal outlines are exactly what they sound like: Very Serious. They wear black ties to parties and never joke around. They often use Roman Numerals (I, II, III, etc.) and sometimes require complete sentences. They will always include the thesis statement/topic sentence, usually in the first two or three lines.

To create a formal outline for a writing assignment, use the prewriting strategies to generate ideas, then create a blank outline using either pen and paper or a word processor like Microsoft Word (which has built-in outline templates). Then, begin filling in your ideas in the order that best makes sense.

For each level, you’ll change the numbering system that you use and increase the indent. The further indented the idea is, the less important it is to the entire paper.

For a paragraph, you might outline first with key words or phrases at each level and then move to complete sentences once the outline is complete; for an essay, write complete sentences at each level.

Here’s an example Formal Outline for the Gifts topic:

- Thesis: The best gift I can offer to the world is the gift of laughter.

- Laughter is really the best medicine.

- Studies have shown that people who laugh heal more quickly from major trauma than those who don’t.

- I often make five or six people laugh at my workplace every day by telling jokes.

- Because I work in a hospital, this is a significant contribution.

- Being funny is harder than it seems, which is why being able to tell good jokes is my gift and hobby.

- Sometimes, people rely on crude or offensive humor, which might get a laugh quickly but doesn’t leave a lingering positive feeling.

- Other times, people have bad timing with their jokes, which can make even the best joke fall flat.

- I’ve studied comedy and have naturally good comedic timing, and I use these skills to brighten others’ days.

- Laughter is really the best medicine.

An Informal Outline may follow a similar shape as a Formal Outline. Information will often be indented to show that it’s a supporting point instead of a major point. However, Informal Outlines are created to be changed, moved, and edited on the fly. Therefore, there’s little need to worry about Roman Numerals or specific levels of indentation. Instead, an informal outline is more like a list of the points you want to make and what you think will work well to support those points.

Informal outlines will usually be written without complete sentences. Instead, plug in key words or phrases that make sense to you.

Informal outlines can be made by hand or typewritten. When they’re typed, they can be easily manipulated by copying sections and pasting them back in. This can help with overall organization.

Visual Outlining Strategies

If the thought of drawing up an outline doesn’t charm you, or if you regularly prefer to learn by moving pieces around or getting hands-on experience (called kinesthetic learning), then visual outlining might be worth a try.

There are many ways to visually outline a piece, and you can invent your own methods to make it work best for you. The idea, though, is that we can move beyond paper and pen to organize our work. This makes sense because when a paper is still in our mind, it’s more than just a flat piece of paper laying in front of someone’s eyes. It’s pictures and sounds; it’s colors and textures. Therefore, as we organize our thoughts, we can use some of that sensory detail to put our work together.

If you’ve ever used Pinterest, you know how addictive it can be to simply stick your ideas to a board — even a virtual one! That same technique can be used to create and organize an assignment, too.

One simple visual outlining strategy is to take major ideas (things that interest you, things you want to talk about, things you’re curious about, good points) from your brainstorming or freewriting and transfer them onto colored pieces of paper or, better yet, sticky notes. Then, using a bigger piece of paper, a desk, a nearby wall, or whatever works for you, move the ideas around until they begin to form a coherent paper.

The act of moving the pieces will stimulate your brain in a different way than simply writing down an outline. Plus, as you visualize the organization, you may see where there are gaps missing.

Again, there are hundreds of ways to visually organize. Just remember that it’s an option!

Review and Take-Aways

Now, we’ve moved through all of the pieces of pre-writing. We’ve analyzed, we’ve brainstormed, we’ve written freely, we’ve mapped, we’ve outlined, and we’ve visualized. It is finally time to get started with writing a draft.

By this point, you should be working from a cluster map, a visual organizer, or some kind of outline. Once you have one of these pieces beside you, the actual drafting should feel like you’re copying from one page and pasting to the other. All that’s left to do is fill in the details — and figure out how to introduce the entire topic!

We’ll dig in to introductions later. For now, start writing in the middle, where the action happens and the point is going to be made. Don’t worry about the first sentence, which is the hardest part to write. Just write down the answer to your question, then start explaining.

Congratulations! You’re drafting!

— The End —