5

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this module, participants will be able to:

- Describe the contributions of pioneers who have helped shape our understanding of anxiety, stress, and fear

- Identify and describe 3 types of exposure therapy

- Identify and describe 3 relaxation strategies

- Describe three elements associated with the process of anxiety recovery

Introduction

There are numerous approaches to treating anxiety, yet treatment options continue to evolve. More specifically, research efforts have paved the way for the use of evidence-supported interventions. One specific approach that has gained significant support and attention is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (American Psychological Association, [APA],2017; Bulter, et al., 2006). When addressing CBT, it can be helpful to think of it as an umbrella term. I say this as several contemporary “third wave” cognitive behavioral approaches have been developed (Gaudiano, 2008). For example, many of the elements utilized in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) are derived from CBT principles.

Conceptualizing outcomes associated with anxiety treatment can be challenging. For example, some practitioners would argue that anxiety can be cured while others believe the opposite to be true. The more dominant paradigm focuses on anxiety treatment as a recovery process vs a cure. The position of this module is geared towards anxiety treatment as a recovery process. It will focus on treatment strategies that target the two pathways to anxiety: cortex and amygdala-based anxiety. This module will introduce four individuals who have played an instrumental role in our understanding and treatment of fear, anxiety, and stress, provide an overview of cognitive behavioral theory and therapy, and highlight specific cognitive and behavioral interventions used to treat anxiety. **NOTE: Within this module, the use of the word anxiety will be as an umbrella term thus including, stress, fear, panic, and worry.

Contributors to Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies

There are several researchers and practitioners who have contributed to our clinical understanding of anxiety (including fear, panic, worry, and stress). Furthermore, these individuals have contributed to the development and evolution of cognitive and behavioral therapies. Because of empirical research, interventions, like theory, are tested and evolve. Highlighted below are four individuals who have played a significant role in developing theory and interventions grounded in CBT.

Dr. Clair Weekes: Dr. Weekes, an Australian physician who is known for her work in treating anxiety. She took more of a behaviorist approach which contradicted some of the work done by earlier physicians including Sigmund Freud. Dr. Weekes believed that teaching relaxation strategies to be used during anxiety, panic, and/or fear was counterproductive. She argued that people need to fully experience the negative emotion (i.e., panic, anxiety, fear) for two reasons. First, to provide evidence that a person can tolerate the discomfort and come out on the other side unharmed. Second, fully experiencing the negative emotion aids in re-wiring the nervous system. To sum up her approach to treating and recovering from anxiety, people must be willing to face and accept the anxiety experience vs fighting and avoiding the discomfort. It is the tight grip on fighting the anxiety that fuels and maintains it. Her primary theme in treatment is to float through the anxiety (Carbonell, 2018; Hoare, 2019; Weekes, 1990). Dr. Weekes approach remains a dominant paradigm in today’s treatment of anxiety. This is particularly true when treating such things as social anxiety, phobias, and agoraphobia.

Dr. Albert Ellis: In the mid 1950’s psychiatrist Dr. Ellis developed rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT). By many, he is known as the grandfather of CBT. His work was often criticized as it was not supported by empirical research/clinical trials, but rather based on experience and subjective client outcomes (DiGiuseppe, 2014). This therapeutic approach is known to be the first type, or first wave, of CBT. This approach focuses on the present and assists in managing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral challenges. Dr. Ellis (1962) argues that it is our thoughts (cognitions) that that impact our emotions and behaviors. In short, this approach focuses on unhealthy/unhelpful emotions (i.e., anxiety, guilt, depression) and maladaptive behaviors (i.e., addiction, aggression) all of which can impact life satisfaction and functioning (Ellis, 1962). You may be most familiar with Dr. Ellis’s A-B-C model where A= activating event, B = rational/irrational beliefs (not behavior) and C= emotional and/or behavioral consequences (DiGiuseppe, 2014). REBT has been supported in treating both anxiety and depression (David et al., 2018)

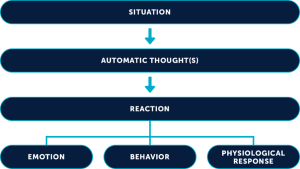

Dr. Arron Beck: Dr. Beck is known as the father of CBT. Dr. Beck argues it is the interaction of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that leads to distress. Furthermore, he believed the interpretation(s) that people attached to their experiences/situations influenced the type of behavioral and emotional reaction they have (See figure 1 cognitive model). He coined these powerful interpretations as “automatic thoughts” as they impact how people experience themselves, others, and their world. By identifying and modifying distorted and unhelpful negative automatic thoughts results in long lasting improved mental health (Beck, 2021; Cristea, 2018).

Dr. Herbert Benson: Dr. Benson is known for promoting the integration of spirituality and medicine. He is the founding father of the Mind/Body Medical Institute at Mass General Hospital. While his initial work does not specifically focus on treating anxiety, he does focus on the health implications of stress which could in turn, if not treated, lead to symptoms of anxiety. Dr. Benson’s extensive research led to the development of “relaxation response.” The relaxation response is opposite that of the stress response. Our body’s, when encountered with a stressful situation, automatically trigger a stress response via the amygdala and sympathetic nervous system (SNS). Dr. Benson’s work teaches us how to dismantle unhelpful stress responses by replacing it with the relaxation’s response. The relaxation response occurs by activating the parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS). For example, to achieve the relaxations response, one could practice meditation as a form of mindfulness, and or muscle relaxation techniques. Since the development of the relaxation response, several researchers have studied this approach in treating anxiety as well as stress (Beck-Henry Institute 2022; Nakao, et al., 2001).

Figure 1: Cognitive Model

(Source: Beck Institute)

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a short-term treatment that focuses on the present rather than spending time attempting to identify the cause of symptoms and distress. This highly structured, goal oriented, skill-based psychotherapy has been effective at treating several mental health disorders including anxiety, depression, and eating disorders (American Psychological Association, [APA],2017; Bulter, et al., 2006).

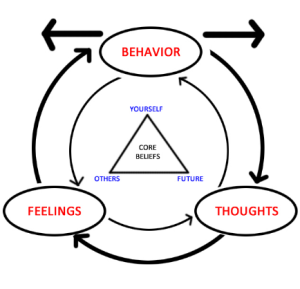

CBT is based on the premise that there is an interplay between a person’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors (See image 2). According to Beck (1964), it is how a person perceives an event rather than the situation itself that leads to distress. Thus, how a person feels is really determined by how a situation is interpreted. The underlying theory of CBT is cognitive theory. When we think of the concept of cognition, we are referring to thoughts and images. The cognitive model illustrates how a person’s thoughts and perceptions influence behaviors and feelings (Beck, 1964). Cognitions are prone to bias such as misappraisals of events and situations which can lead to anxiety and depression (Beck et al., 1979). One of the goals is to assist clients in learning how to develop more adaptive cognitions and behaviors (Fenn and Byrne, 2013). Theoretically, there are three levels of cognition that are part of the cognitive model: core beliefs, dysfunctional assumptions, and automatic negative thoughts (Beck, 1979).

Image 2: CBT Interactional Elements

(Source: Wikimedia, Depicting basic tenets of CBT)

Core beliefs, also referred to as schemas, are deeply held beliefs about oneself, others, and the world. These beliefs are formed early in life and are influenced by experiences starting in childhood such as relationships with one’s peers, teachers, and/or caregivers. Early challenging life experiences (i.e., bullying or caregiver neglect) can lead to problematic or maladaptive core beliefs. If you were abused as a child (life experience) you may struggle developing intimate relationships or fear abandonment. As a result, you may hold the belief “I cannot trust you because you will hurt me.” More specifically, problematic core beliefs might include, feeling like a failure, unlovable, boring, flawed OR hold the belief that some people are manipulative/cannot be trusted or that the world is a dangerous place. It is important to note that some core beliefs are protective while others are problematic. Healing is often about learning to discern the difference in any given moment. These beliefs can be difficult to change as they are deeply embedded within the cognitive parts of our brain (Beck, 1979).

Dysfunctional assumptions, also known as conditional beliefs, influence how a person responds to life experiences and situations. These assumptions are the product of a person’s core beliefs and influence automatic thoughts. It is believed that these assumptions are the rules in which people live by. These assumptions tend to be rigid (inflexible), not based in reality, and can result in problematic or unhelpful behaviors (i.e., avoidance behaviors, substance use). These assumptions tend to show up in statements/thoughts containing “if…then…should.” Some of these rules may enhance our lives while others are problematic thus leading to distress (Schaffner, 2021).

Automatic thoughts (AT’s) are just that. They are thoughts that happen on an unconscious level thus outside of one’s awareness. AT’s occur in response to a cue or trigger and can have a neutral, negative, or positive effect. When an experience leads to a negative effect the thoughts associated with this experience are called negative automatic thoughts (NAT’s). NAT’s are often irrational and self-defeating thus impacting how we feel and behave (Cuncic, 2020). One of the goals of CBT is develop skills in thought awareness.

Cognitive Distortions

Beyond the three types of cognitions are what cognitive-behaviorists call cognitive distortions (also known as thinking errors or biased thinking). Cognitive distortions are considered irrational and negative thinking patterns (Hartney, 2021). More specifically, they are biased perspectives that influence how we view ourselves and our world (Ackerman, 2021). These errors in thinking are so automatic and patterned that they can be difficult to bring into awareness and modify. The effects of distorted thinking can lead to and/or provoke symptoms of anxiety and depression (Ackerman, 2021). There are approximately eleven common cognitive distortions that have an influence on anxiety and depression (Beck, 1972; Mathews et al., 1997).

Click the link below for a list and description of cognitive distortions

https://www.verywellmind.com/ten-cognitive-distortions-identified-in-cbt-22412

Cognitive and Behavioral Strategies for Treating Anxiety Disorders

There are several cognitive and behavioral strategies to treat anxiety disorders. These interventions assist in the process of rewiring the brain thus having an influence on the two pathways to anxiety.

For a quick review of the pathways, check out this brief video or revisit module 3:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xgzFQZ14qyc

Cognitive restructuring

Cognitive restructuring (also known as reframing) is a structured and collaborative process where a client learns how to identify, evaluate, and modify problematic/unhelpful NAT’s (Beck et al., 1985). This process involves self-monitoring, tracking thoughts, labeling distortions, reality testing, addressing consequences (i.e., behaviors or emotions), and developing alternatives in thinking (Beck et al., 1979). Theoretically, engaging in the process of cognitive restructuring allows for the testing of one’s thinking and should result in awareness and modification of core beliefs, automatic thoughts, and cognitive distortions. Furthermore, it aims to help people manage and reduce distress through fostering functional thought habits and to experience more balanced thinking (Mills, et. al., 2018). It is cognitive restructuring that targets the cortex pathway to anxiety (Pittman, et al., 2015).

To learn more information about cognitive restructuring from a theoretical lens visit:

Option 1:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/9781118528563.wbcbt02

Option 2:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=58RytIerkmc

There are several tools used in the process of cognitive restructuring. One popular tool is a thought record. There are several variations of thought records. In general, they include situation/trigger, feelings, unhelpful thoughts/images, facts that support the unhelpful thoughts/images, facts that provide evidence against unhelpful thoughts/images, alternative more helpful/realistic and balanced view, and outcomes. These are to be completed on a daily basis and are often processed during therapy sessions. In addition to thought diaries, there are phone apps such as CBT thought diary, moodfit, worry watch, and daylio that can be used to track thoughts etc. While some of these have free features, some may have additional costs. Thus, if you plan to use these options with your clients, make sure to assess to see if they are accessible and affordable.

To see an example of a thought record template visit:

https://beckinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Thought-Record-Worksheet.pdf

To see an example of a therapist using cognitive restructuring with a client visit here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJ1eDL15_Lw

Exposure

Exposure therapy is known to be an evidence-based supported intervention to treat anxiety disorders including specific phobias, agoraphobia, social anxiety, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (Kaczkurkin, et al., 2015). During the process of exposure therapy (also known as systematic desensitization), the clinician assists the client in confronting and overcoming their fears/phobias by systematically and gradually exposing them to the trigger/stimuli that leads to feelings (and sensations) of anxiety and fear. More specifically, the trigger or stimuli could be a thought, image, object, or situation. The amygdala (our fear center) learns through experience which is why exposure therapy is so successful. Engaging in avoidance behavior is natural for those with specific fears/phobias but, avoidance has the opposite effect thus fueling and exacerbating symptoms of anxiety and fear. As a result of engaging in exposure work, it can lead to habituation. Habituation is when the original reaction towards the stimulus diminishes in intensity or even disappears (Eelen & Vervliet, 2006). While exposure therapy is successful at treating certain anxiety disorders, it is not guaranteed. It has been identified that between 10% – 30% of people do not have success with exposure therapy in that the fear returns shortly after the completion of treatment (Craske, 1999).

Inhibitory learning theory (ILT) helps explain the issues associated with short-term or limited effectiveness of exposure treatment. Inhibitory learning theory aids in understanding the process of fear extinction. Lang et al., (1999) state that “the idea behind ILT is that the original threat association learned during fear acquisition is not erased or replaced by new learning. Rather, the conditioned stimulus becomes ambiguous with two meanings that both live in memory and compete for retrieval (retrieval competition).” Because the fear or anxiety provoking memory remains in our brain after treatment, it is often referred to as a competition of which memory will be activated when exposed to the trigger/stimuli. It is this theory that may explain why habituation does not always provide long-term management of anxiety. Here is a great example I borrowed from the International OCD Foundation. “Within the inhibitory learning framework, exposure therapy is designed to teach what “needs to be learned” to disconfirm these feared outcomes. For example, someone with obsessions about harm may predict that if they are alone with a baby for 30 minutes, they will lose control and harm the child. Thus, an exposure exercise is designed to directly disconfirm this prediction, perhaps by handling an infant while alone for 45 minutes and keeping track of whether any harmful acts are committed. To facilitate extinction learning, each exposure practice is focused on determining whether the expected negative outcome occurred (rather than waiting for anxiety to habituate)” (International OCD Foundation, n.d.).

There are four different approaches to exposure therapy: in-vivo, imaginal, flooding, and interoceptive (more recently, virtual reality which is a type of imaginal). Before jumping into the three types of exposure, I briefly want to introduce exposure and response prevention (ERP). ERP is like other types of exposure therapies, but it has an additional element which is response prevention and is exclusively used to treat obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Once exposed to a trigger/stimuli (i.e., germs on a door knob) the client makes a choice not to engage in compulsive behaviors (ritualistic handwashing) to decrease levels of distress. The commitment to not engage in the compulsion (i.e., handwashing after touching dirty doorknob) prevents reinforcing the obsession (fear of germs). Theoretically, when a client keeps engaged with the trigger/stimuli, chooses not to engage in the compulsive behavior, and when the symptoms of anxiety decrease, this is again an example of habituation.

To read more on ERP, visit the following link:

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/therapy-types/exposure-and-response-prevention

Let’s investigate three types of exposure. In-vivo (meaning in real life/time), is a when a client is gradually exposed to activating or provoking trigger or stimuli. The goal with gradual exposure is desensitization which means to reduce or eliminate the fear (stress response) response to specific trigger/stimuli (McLeod, 2021). Furthermore, a gradual approach supports small achievements which fosters confidence. As part of this exposure process, McLeod (2021) suggests three important steps. First, clients should learn how to use and implement muscle relaxation techniques (i.e., progressive muscle relaxation). Second, is to assist the client in creating a fear hierarchy. The hierarchy should begin with things that are the least provoking and end with the most provoking. For example, a person who has an extreme fear of spiders might start with looking at a picture of a spider and ending with the handling of a spider. It is during the development of the hierarchy when a client will apply the Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS) next to each trigger (See module #4 for a refresher on SUDS). Third, assist the client in working through their hierarchy. They will begin with the least anxiety provoking scenario or activity to the highest. The process of desensitization typically takes place over several sessions. However, some clinicians may modify their approach to treating specific phobias. For example, Dr. David Barlow who is the Director of the Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders at Boston University, works with clients in a shorter timeframe to desensitize them to their phobias. Access the link below to see Dr. Barlow work with a client in addressing their fear of snakes. Dr. Barlow. Fear of snakes:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKTpecooiec

Imaginal exposure therapy uses the process of guided imagery to expose a client to provoking triggers/stimuli which results in fear and anxiety. As with in-vivo therapy this is a gradual exposure process and requires the clinician to work with the client in developing a fear hierarchy. It is also important to prepare the client by first teaching skills in relaxation. There are different approaches to imaginal exposure therapy. For example, research supports the use of virtual reality (VR). A study conducted by Dr. Rosembaum (2000), used VR to desensitize those who had a fear of flying. The results indicated the intervention was successful at reducing anxiety as compared to those who did not receive VR treatment. In the end, imaginal exposure may not be as effective when compared to in-vivo as it provides an additional layer of safety given the exposure is imagined.

Flooding is the most extreme approach to treating phobias as it begins with the most provoking trigger/stimuli. This contrasts with both in-vivo and imaginal exposure therapy as they begin with the least provoking triggers/stimuli. Given that phobias are a learned fear, the process of flooding assists in unlearning that fear. This type of approach is not always feasible (i.e., filling a room with spiders).

Interoceptive exposure therapy works by triggering or activating feared sensations with the goal of distress tolerance (Blakely, et al., 2018). In a nutshell it is about inducing the sensations of anxiety (i.e., dizziness, lightheadedness, shortness of breath) while learning how to reduce sensitivity to the sensations. There are numerous activities that can be implemented to activate such sensations including straw breathing, spinning in a chair, shaking head side to side etc. For more specifics on these types of activities, visit the Beck Institute website:

https://beckinstitute.org/blog/health-anxiety-and-interoceptive-exposure/

To see interoceptive exposure therapy in action, visit the following link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M2Bou5nBONA

Relaxation Strategies

The implementation of relaxation strategies can aide in both preventing and managing symptoms of anxiety. These strategies are like a fitness routine in that they need to be practiced frequently and, in many cases, daily. It is important to note that the use of relaxation strategies during challenging moments (i.e., during a panic attack) can be counterproductive. Why? Engaging in such strategies can send a false message to the amygdala indicating that a person is unable to tolerate distress. As part of the re-wiring process, we want to create a message that we are resilient and strong and can manage anxiety regardless of the pathway. This links back to the work of Dr. Weekes in “floating” through the anxiety experience.

It can be easier to chase target symptoms of anxiety and discomfort vs having to face one’s fears. The fear approach would require a person to do the exact opposite of what the amygdala (survival mode) is telling you to do (Weekes, 1990; Linsalata, 2021). A primary anxiety treatment goal is to address and eliminate any irrational fears and stress reactions (Linsalata, 2020). It is natural and common to hyperfocus on bodily sensations (i.e., rapid heart rate) and thoughts or images (imagining oneself having a panic attack on an airplane). However, in both cases, the goal is to simply notice the thoughts, images, and sensations without triggering a stress response. For example, escaping an anxious producing situation time after time simply reinforces the power of the stress response and associated symptoms (Pittman and Karle, 2015). In the end, escape only provides short-term relief. Again, the amygdala learns experientially so repeating a new and healthier strategy will change your stress response. Repeat this process over and over as it assists in re-wiring of the anxious brain.

To assist in the recovery process, there are a variety of relaxation strategies that can be used to prevent as well as aid in reducing the severity and duration of anxiety symptoms. Specifically, these strategies work to calm or diffuse the amygdala’s activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). While these strategies are important in reducing activation of the SNS (stress response- fight, flight, or freeze), they also stimulate the PSNS (rest and digest…calming effect). As a refresher, the PSNS assists in the regulation or breathing, heart-rate, and blood flow. The most useful relaxation approaches include breath work, muscle relaxation, and meditation.

Certified mental health counselor and anxiety specialist, Sheryl Ankrom (2022), outlines several breathing relaxation strategies. The most common exercises include diaphragmatic breathing, box breathing, and pursed-lip breathing. Let’s take a more in depth look at diaphragmatic breathing. This exercise is known to activate the parasympathetic nervous system (Pns) which is also true with most breath work exercises (Bourne, et al., 2004). Place one hand on the belly and breathe in slowly through your nose and exhale slowly through your mouth (recommended to slightly purse your lips on the exhale). With the hand that is on the belly, you should feel your hand go up and down with each breath. For a more comprehensive explanation of the different types of breath work exercises, visit the following link:

https://www.verywellmind.com/abdominal-breathing-2584115

The most common type of muscle relaxation is progressive muscle relaxation which was first introduced by Dr. Edmund Jacobson (1938). Constant muscle tension leaves people quite fatigued. This exercise involves intentionally and systematically tensing certain muscles groups and then relaxing. It typically begins with the feet and progresses up to the head. The process of muscle relaxation aids in developing awareness of what it feels like to experience tension as well as relaxation. Developing an awareness of tension results in a cue to relax especially when feeling stress or anxiety. Furthermore, it can assist in more readily being able to relax and manage anxiety symptoms when the amygdala has been activated (again, activation of the parasympathetic nervous system-PSNS). This approach also is useful in calming the pre-frontal cortex pathway to anxiety. Where do you tend to hold your tension? In your shoulders? back? Jaw (clenching)? Taking inventory of where a person holds their tension is the first step in the process of understanding progressive muscle relaxation. To experience the process of progressive muscle relaxation, go to the following link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1nZEdqcGVzo

While there are many different types and approaches to meditation, mindfulness meditation is one of the most popular types. Research has shown that mindfulness meditation is helpful in deactivating both cortex and amygdala-based anxiety (Goldin and Gross, 2010). Mindfulness meditation is about being in the present moment and doing so requires awareness, free from judgment, curiosity, and self-compassion (Brewer, 2022). In a nutshell, the practice is about noticing when your mind wonders, detach/drop the thought, and coming back to your anchor which is often a person’s breath. People often assume meditation is about NOT thinking. It is more about developing an awareness of the present moment and noticing when the mind begins to wander (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). Dr. Herbert Benson’s relaxation response (activation of the PSNS), has close ties to the work of Dr. Kabat-Zinn on mindfulness meditation (Beck-Henry Institute 2022). Both approaches work at improving health and mental health. Given the increase in popularity and demand for meditation support, there are several apps as well as websites that can assist individuals with meditation options. For example, there are numerous resources online on how to meditate, guided meditations, and music for meditation. Popular apps and websites for mindfulness meditation practice include insight timer, calm, headspace, and ten percent happier.

To experience a guided meditation targeting anxiety, access the following link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O-6f5wQXSu8

Additional items to consider when treating anxiety disorders

- Safety behaviors (also known as coping behaviors) are self-protective behaviors/strategies a person engages in as a mode of protection when experiencing a threat and/or anxiety. Taking an inventory of these behaviors and addressing them as part of the treatment process is critical. It is natural to think of these behaviors as helpful and beneficial, but they can prolong and exacerbate anxiety symptoms. It may be true that these behaviors provide immediate relief, but the relief will be short-term (Myhre, n.d.). Engaging in safety behaviors tricks the brain into thinking a person cannot tolerate distress and that they need such behaviors to feel in control and to feel safe. Examples of safety behaviors include avoidance (i.e., avoidance of social situations, enclosed places, certain thoughts), checking behavior (i.e., lock on doors, locating nearest bathroom, monitoring blood pressure), constant reassurance from others, and use of safety aids (i.e., always having food nearby, rescue medication such as Xanax, water bottle).

- Psychoeducation is an important element of CBT. It involves educating the client on many elements related to their anxiety and anxiety diagnosis. For example, explaining the two pathways to anxiety from a neuroscience perspective can be helpful. That is, the role of the brain in activating a stress response. Or you may provide a client with skill building around the use of mindfulness meditation as a method for relaxation. Consider assisting a client who struggles with social anxiety, and you provide social skills training. What other types of psychoeducation can you imagine providing your client that relates to treating anxiety?

- Understanding the Solution. Author, podcaster, and anxiety expert, Drew Linsalata eloquently identifies several solutions or processes to assist those struggling with anxiety. I want to note that the foundation of his approach to anxiety recovery is based on the work of Dr. Claire Weekes and Dr. Aaron Beck. In Mr. Linsalata’s Book (2020), “The Anxious Truth” he outlines several steps for successful anxiety recovery. Most of these step’s aid in re-wiring the anxious brain such as with the process of neuroplasticity. Here is a brief overview of these steps:

- Surrender– While this may not feel comfortable, it is important to stop resisting/fighting the fear, panic, and anxiety. It is natural to want to feel safe but not surrendering will keep a person feeling stuck in the cycle of always dealing with fear, panic, and anxiety.

- Do the opposite- When a person feels as if nothing is helping their anxiety, have them evaluate what strategies are being used. Although this may sound counterproductive but doing the opposite of what you are doing is often what is needed. For example, take an inventory of any safety behaviors (i.e., avoidance, use of safety aids) you engage in. The motivation for utilizing safety behaviors is to feel safe and comfortable. In a nutshell, doing the opposite also means doing nothing.

- Change your focus– Individuals who get caught up in a cycle of anxiety are hyperalert, hypersensitive and often hyperfocus on their thoughts and bodily sensations. Such as the saying, “what we resist, persists.” Day to day, this focus can be disruptive and time-consuming. Mr. Lisalata (2020, p. 146) calls this as having an “anxiety-based inward focus” thus being consistently stuck in one’s own head/mind. It is natural to fall into these cognitive and behavioral processes as it is the body’s way of scanning for possible threats. Develop skills that aid in focusing outward.

- Stop avoiding- Simply put, this means leaning into fear, panic, and anxiety vs running from it. Engaging in avoidance makes the symptoms worse and, in many cases, can exacerbate symptoms. Learn how to be present with the uncomfortable thoughts, images, bodily sensations etc. This is where exposure therapy can be extremely helpful as it works with people to stay present with the fear, anxiety, and discomfort. This suggestion is exactly what Dr. Clair Weekes proposed in her early work in treating people with anxiety disorders.

- Examine your reactions- Cognitive behavioral therapists argue that it’s not so much how you feel that is problematic when you experience anxiety, but rather how you react. Breaking it down further, how you react to anxiety takes place at three stages: before exposure to a trigger/stimuli (i.e., anticipatory anxiety), during, and after. Assess the cognitive and behavioral reactions a person experiences at each stage. How might these reactions keep a person stuck in the same anxious feedback loop?

- Learn new skills- The key to managing/solving anxiety is not only learning how a person reacts, but also learning new skills. Linsalata (2020, p. 200) clearly states, “these skills are not prevention or escape measures…..these are tools you will use to maintain a state of non-reaction, even at the height of panic….Remaining physically relaxed and mentally calm while anxiety and panic rage around you will help it all to end sooner, but it will not make it end immediately.” Skills that are helpful in the recovery process include mindfulness meditation, breath work, and relaxation techniques (i.e., progressive muscle relaxation). Do any of these suggestions around relaxation ring a bell? This is exactly what Dr. Herbert Benson, whom you read about at the onset of this chapter, proposed based on his research related to the relaxation response.

- Persistence and patience- Change takes time and so does the process of anxiety recovery. It is common for anxiety sufferers to want immediate results, but the recovery process takes time, persistence, patience, and self-compassion.

Here is a great video that discusses rewiring the anxious brain:

Conclusion

This chapter provided an overview of cognitive behavioral approaches to the treatment and recovery of anxiety disorders. CBT in general has been deemed highly successful in treating various mental health disorders. While CBT related theories, models, and concepts have been around for centuries, they continue to evolve. Just like testing out a recipe, interventions used to treat anxiety disorders are rigorously tested in clinical trials. It is through these trials where evidence-supported interventions are “re-packaged” and used in real world settings. One of the goals is to make supported interventions more assessable.

Learning Activities

- Identify and describe the three types of cognition associated with CBT.

- Discuss your understanding of the link between habituation and inhibitory learning theory as they both relate to the treatment of anxiety.

- You are working with an adult male client who has a diagnosis of panic disorder. As part of the conversation, you explain to your client various steps associated with “understanding the solution” to managing his anxiety. Identify and describe three concepts associated with understanding the solution to treating anxiety as outlined by anxiety expert Drew Linsalata.

- You are giving an in-service training at a local mental health agency. You are discussing treatment options for treating specific phobias. As part of your training, you review the four types of exposure therapy. Identify and briefly describe each type of exposure therapy. Last, how would you explain the rationale for using exposure therapy as a supported intervention?

References

Ackerman, A. (June 12, 2021). Cognitive Distortions: When Your Brain Lies to You. https://positivepsychology.com/cognitive-distortions/

American Psychological Association [APA], (2017). What is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/patients-and-families/cognitive-behavioral#

Ankrom, S. (Feb. 14th, 2022). 8 Deep Breathing Exercises for Anxiety. https://www.verywellmind.com/abdominal-breathing-2584115

Beck., J. & Fleming, S. (2021). Editorial: A Brief History of Aaron T. Beck, MD, and Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Clinical Psychology in Europe. https://cpe.psychopen.eu/index.php/cpe/article/view/6701/6701.html

Beck, A. T., & Emery, G. & Greenberg, R. (1985). Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive perspective. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Beck, A. T., Rush, J., Shaw, B., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guildford Press

Beck, Aaron T. (1972). Depression; Causes and Treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Beck, J. S. (1964) Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond, New York: Guildford Press.

Benson-Henry Institute (2022). Abou. Dr. Herbert Benson. https://bensonhenryinstitute.org/about-us-dr-herbert-benson/

Benson-Henry Institute (2022). Historic Conversation Between Pioneers of Mind-Body/Integrative Medicine https://bensonhenryinstitute.org/historic-conversation-between-pioneers-of-mind-bodyintegrative-medicine/

Blakey, S.M. & Abramowitz, J.S. (2018). Interoceptive Exposure: An Overlooked Modality in the Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of OCD. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 25, 145-155

Butler, A. C., Chapman, J. E., Forman, E. M., & Beck, A. T. (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev. 26, 17–31.

Bourne, E. J., A. Browstein, and L. Garano. (2004). Natural Relief for Anxiety: Complementary Strategies for Easing Fear, Panic, and Worry. New Harbinger.

Brewer, J. (2021). Unwinding anxiety: new science shows how to break the cycles of worry and fear to heal your mind. Avery publishing

Carbonell, D. (2022). Claire Weeks: Float through anxiety. Retrieved from https://www.anxietycoach.com/claire-weekes.html

David, D., Cotet, C., Matu, S., Mogoase, C., Stefan, S. (2018). 50 years of rational-emotive and cognitive-behavioral therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 74(3):304-318. doi:10.1002/jclp.22514

Craske, M. G. (1999). Anxiety disorders: Psychological approaches to theory and treatment. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Cristea, D.D., & Hofmann, S.G. (2018). Why cognitive behavioral therapy is the current gold standard of psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, Article 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00004

Cuncic, A. (Nov. 27th, 2020). Negative Automatic Thoughts and Social Anxiety. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-are-negative-automatic-thoughts-3024608

DiGiuseppe, R.A., Doyle, K.A., Dryden, W., & Backx, W. (2014). A Practitioners Guide to Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (3rd ed). Oxford University Press.

Jacobson, E. (1938) Progressive Relaxation: A Physiological and Clinical Investigation of Muscular States and Their Significance in Psychology and Medical Practice, (2nd ed.), University of Chicago Press.

Eelen, P., & Vervliet, B. (2006). Fear conditioning and clinical implications: What can we learn from the past? In M. G. Craske, D. Hermans, & D. Vansteenwegen (Eds.), Fear and learning: From basic processes to clinical implications. (pp. 17–35). Washington, DC US: American Psychological Association.

Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy. Lyle Stuart.

Fenn, K., & Byren, M. (2013). The key principles of cognitive behavioural therapy. InnovAiT, 6(9), 579-585.

Gaudiano, B. (2008). Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies: Achievements and Challenges. Evidenced-based mental health, 11 (1), 1-7.

Golding, P. R., & Gross, J. J. (2010). Effects of Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on Emotion Regulation in Social Anxiety Disorder. Emotion, 10, 83-91.

Hartney, E. (Nov. 13, 2021). 10 Cognitive Distortions Identified in CBT. https://www.verywellmind.com/ten-cognitive-distortions-identified-in-cbt-22412

Hoare, J. (2019, September 21). Face, accept, float, let time pass: Claire Weekes’ anxiety cure holds true decades on. The Sydney Morning Herald, https://www.smh.com

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. 1994. Wherever you go, there you are: mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion.

Kaczkurkin, A. N., Foa, E. B. (2015). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: an update on the empirical evidence. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 17(3):337-346. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.3/akaczkurkin

Lang, A. J., Craske, M. G., & Bjork, R. A. (1999). Implications of a new theory of disuse for the treatment of emotional disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6(1), 80-94.

Linsalata, D. (2020). The Anxious Truth. Bookmark Publishing.

Myhre, S. (n.d.). Safety Behaviors: Why we do Them and How CBT Can Help. https://www.austinanxiety.com/safety-behaviors/

Nakao, M., Fricchione, G., Myers, P., Zuttermeister, P.C., Baim, M., Mandle, M.C., etc. (2001). Anxiety is a good indicator for somatic symptom reduction through behavioral medicine intervention in a mind/body medicine clinic. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 70 (1), pp. 50-57. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11150939/

Mathews, A., Mackintosh, B., & Fulcher, E. P. (1997). Cognitive biases in anxiety and attention to threat. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 1(9), 340-345.

McLeod, S. (2021). Systematic Desensitization as a Counter-conditioning Process. https://www.simplypsychology.org/Systematic-Desensitisation.html

Mills, H., Reiss, N. & Dombeck, M. 2008. Cognitive restructuring. Mental Help Net. https://www.mentalhelp.net/articles/cognitive-restructuring-info/

Pittman, C.M., & Karle, E.M. (2015). Rewiring the anxious brain. How to use the neuroscience of fear to end anxiety, panic and worry. New harbinger publications.

Rothbaum, B. O., Hodges, L., Smith, S., Lee, J. H., & Price, L. (2000). A controlled study of virtual reality exposure therapy for the fear of flying. Journal of consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(6), 1020.

Schaffner, A. K., (June, 6, 2021). Identifying and Challenging Core Beliefs: 12 Helpful Worksheets. Positive Psychology, https://positivepsychology.com/core-beliefs-worksheets/

Weekes, C.H. (1990). Hope and help for your nerves: End anxiety now. Berkley.