Bridging the Gap by Enhancing Cognitive Ability in Nursing Education and Workplace Training through Inclusive Design

Kari Matthews

Abstract

Accessibility in education extends far beyond ramps, elevators, or braille signage. The twenty-first-century challenge is cognitive accessibility and ensuring that learning environments support the needs of students who process information differently. Adult learners in high-stakes programs such as nursing face especially steep hurdles, such as theoretical content, accelerated course schedules, and the expectation that knowledge will be applied flawlessly in patient-care settings. When instruction, digital platforms, and assessment practices fail to account for disabilities such as ADHD, dyslexia, or executive function disorders, learners experience a triple burden of academic disadvantage, professional risk, and stigma.

Accessibility in education extends far beyond ramps, elevators, or braille signage. The twenty-first-century challenge is cognitive accessibility and ensuring that learning environments support the needs of students who process information differently. Adult learners in high-stakes programs such as nursing face especially steep hurdles, such as theoretical content, accelerated course schedules, and the expectation that knowledge will be applied flawlessly in patient-care settings. When instruction, digital platforms, and assessment practices fail to account for disabilities such as ADHD, dyslexia, or executive function disorders, learners experience a triple burden of academic disadvantage, professional risk, and stigma.

This chapter examines those barriers and proposes a holistic response grounded in the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework. First, it synthesizes current scholarship on disability services, technology integration, and web accessibility to illustrate why cognitive equity remains elusive despite robust legal mandates like the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Ontario’s Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA). Second, it outlines practical strategies like multimodal representation, flexible assessment, adaptive digital tools, and policy levers that collectively build an inclusion ecosystem. Third, it presents two case studies (a community-hospital nursing orientation and an online Bachelor of Science in Nursing program) demonstrating measurable gains in learner satisfaction, retention, and clinical competence after UDL adoption. Finally, it offers implementation guidance that balances pedagogical ideals with budgetary, infrastructural, and cultural constraints.

By reframing accessibility as an innovation driver rather than mere compliance, institutions can safeguard patient safety, elevate student success, and model social responsibility. The roadmap provided empowers instructional designers, faculty, administrators, and policymakers to transform nursing education. This extends the adult workplace training into a cognitively inclusive environment where every learner can thrive.

Introduction

Nursing education occupies a unique connection of theoretical knowledge and safe practical skills. Students must assimilate pharmacological pathways, physiological hierarchies, professional ethics, and rapidly evolving evidence-based practices. They then must translate that knowledge into split-second decisions on the ward. For many adult learners, this occurs while juggling family responsibilities, shift work, and financial pressures. When a cognitive disability is layered atop these demands, the risk of disengagement, attrition, or unsafe clinical practice escalates sharply.

Nursing education occupies a unique connection of theoretical knowledge and safe practical skills. Students must assimilate pharmacological pathways, physiological hierarchies, professional ethics, and rapidly evolving evidence-based practices. They then must translate that knowledge into split-second decisions on the ward. For many adult learners, this occurs while juggling family responsibilities, shift work, and financial pressures. When a cognitive disability is layered atop these demands, the risk of disengagement, attrition, or unsafe clinical practice escalates sharply.

Legal frameworks, institutional mission statements, and accreditation standards routinely champion “equitable” or “inclusive” learning. Yet data reveals persistent gaps. Bain de Los Santos et al. (2019) found that students with disabilities at four-year universities graduated at rates up to 18 percentage points lower than their nondisabled peers, even when disability services were nominally in place. In Canada, CBC’s The National (2020) documented how pandemic-era virtual learning magnified those disparities for students with learning disabilities, citing inaccessible platforms and untrained faculty as primary culprits.

Why do these gaps exist? First, cognitive disabilities are often invisible. First, students may avoid self-disclosure for fear of stigma (Timmerman & Mulvihill, 2015). Second, many nursing curricula rely on didactic lectures, dense textbooks, and high-stakes multiple-choice examinations. These formats disproportionately tax memory, processing speed, and executive function. Third, digital courseware and hospital learning-management systems (LMSs) are frequently procured without rigorous accessibility vetting, thereby disregarding the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) (W3C, 2025) guidelines for keyboard navigation, screen-reader compatibility, and captioning.

The issues are more than academic. New nurses who graduate without fully mastering theoretical content may struggle with medication calculations, fail to recognize subtle clinical cues, or omit critical documentation. Patient safety, institutional liability, and regulatory compliance are crucial safety issues that could be impacted.

In this environment, the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework emerges as a proactive and strategic guide to fostering accessibility and equity. Rather than relying on individualized accommodations enacted only after a learner discloses a disability, UDL advocates by designing a curriculum that is flexible from the outset. It does this by anticipating human variations in perception, cognition, and engagement (CAST, 2018). When paired with thoughtfully selected digital tools, UDL can transform nursing education from a one-size-fits-all model into a learning ecosystem where diverse cognitive profiles are assets rather than obstacles.

This chapter proceeds in several stages. It will introduce UDL’s theoretical framework and relevance to nursing and explore the empirical literature on disability services, technology, and web accessibility. In addition, it will analyze specific cognitive barriers in nursing and adult workplace training and outline instructional design solutions and digital resources. Two case studies will illustrate this. Finally, it will discuss the implementation challenges and policy recommendations and conclude by re-emphasizing cognitive accessibility as both an ethical mandate and a strategic advantage.

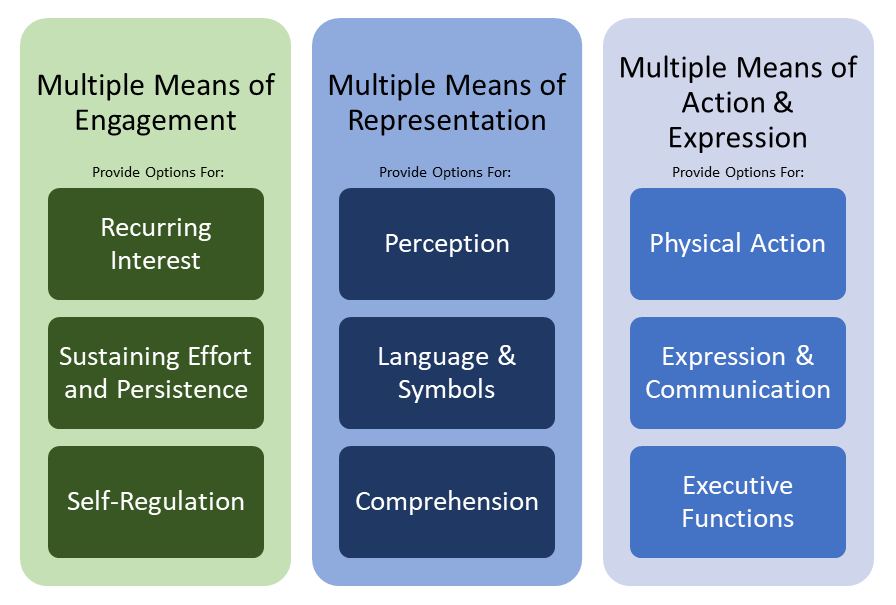

Theoretical Framework: Universal Design for Learning

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) originated in the late 1980s at the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST). It was conceptualized as an educational counterpart to universal design in architecture. Curb cuts, for instance, are intended to support wheelchair users but also assist individuals pushing strollers or carts. Similarly, UDL is based on the premise that designing curriculum with diverse learner needs in mind enhances accessibility and effectiveness for all students. Neuroscientific research on learning networks grounds the framework in three core principles (CAST, 2024):

- Multiple Means of Representation (MMR) – Learners perceive and comprehend information differently. Text, audio, video, infographics, tactile models, and captioned lectures all serve distinct cognitive strengths.

- Multiple Means of Action and Expression (MMAE) – Learners navigate learning tasks and demonstrate knowledge through varied modalities. Allowing choices such as oral exams, multimedia projects, concept maps, or simulation performance reduces executive function strain.

- Multiple Means of Engagement (MME) – Motivation, persistence, and self-regulation hinge on relevance, autonomy, and supportive challenge. Options for collaboration, real-world scenarios, and self-reflection sustain effort.

In nursing, MMR might include 3-D anatomy apps and narrated micro-lessons. MMAE may manifest as a choice between writing a care-plan analysis or recording a screencast. MME may involve connecting pathophysiological concepts to real patients the learner has cared for. These approaches strengthen emotional engagement and reinforce clinical relevance.

UDL aligns with Knowles’s andragogy, which emphasizes self-direction and experiential relevance. It also complements the principles of competency-based education, in which advancement is driven by mastery of skills rather than time spent in class. Importantly, UDL is not solely a disability framework. Research shows that nondisabled students likewise benefit from multimodal redundancy and choice (McGinty, 2018).

Critically, UDL shifts responsibility from the individual student to the learning environment. Instead of requiring a learner with dyslexia to request extended time, the instructor embeds reading alternatives (audio, summary notes) and formative checkpoints so no single high-stakes exam determines success. For nursing programs, this approach cultivates a culture of safety by mirroring clinical practice, where redundancies (e.g., barcode medication administration) are designed to catch human variability before harm occurs.

Literature Review

Disability-Service Efficacy

Data-driven analysis reveals the inconsistent effectiveness of disability services across post-secondary campuses. Bain de Los Santos et al. (2019) reported that faculty awareness and service visibility predicted utilization, yet only a limited number of eligible students registered. Chiu, Johnston, Herbert, and Niu (2019) reported improvements in grade point averages among students who accessed support services. However, persistent barriers remained, including burdensome documentation processes and cultural stigma. In the context of nursing education, researchers at Brandon University (n.d.) described instances where students chose to conceal their disabilities due to prior experiences of discrimination during clinical placements.

Data-driven analysis reveals the inconsistent effectiveness of disability services across post-secondary campuses. Bain de Los Santos et al. (2019) reported that faculty awareness and service visibility predicted utilization, yet only a limited number of eligible students registered. Chiu, Johnston, Herbert, and Niu (2019) reported improvements in grade point averages among students who accessed support services. However, persistent barriers remained, including burdensome documentation processes and cultural stigma. In the context of nursing education, researchers at Brandon University (n.d.) described instances where students chose to conceal their disabilities due to prior experiences of discrimination during clinical placements.

Technology Integration and Learner Engagement

D’Angelo (2018) conducted a synthesis of thirty empirical studies examining the relationship between educational technology and curriculum alignment. Her findings emphasize that intentional, pedagogically grounded integration of technology significantly enhances student engagement and academic achievement. D’Angelo strongly critiques the practice of implementing “tech for tech’s sake,” cautioning that without clearly defined instructional objectives, digital tools risk becoming superficial enhancements that may hinder rather than support learners. This is particularly recognized in those with cognitive processing challenges.

D’Angelo (2018) conducted a synthesis of thirty empirical studies examining the relationship between educational technology and curriculum alignment. Her findings emphasize that intentional, pedagogically grounded integration of technology significantly enhances student engagement and academic achievement. D’Angelo strongly critiques the practice of implementing “tech for tech’s sake,” cautioning that without clearly defined instructional objectives, digital tools risk becoming superficial enhancements that may hinder rather than support learners. This is particularly recognized in those with cognitive processing challenges.

Web Accessibility and the “Curb-Cut Effect”

Digital Education Strategies (2019a) introduced the term “curb-cut effect” within the context of accessible web design. This concept illustrates how features such as video captioning not only support individuals with permanent disabilities but also benefit English as a Second Language (ESL) learners, users experiencing situational limitations (e.g., nurses working in noisy clinical environments), and even contribute to improved search engine optimization. In their subsequent publication, Digital Education Strategies (2019b) reframed accessibility through a strategic lens, by positioning it as both a form of risk mitigation and an avenue for market growth. This business-oriented perspective has been widely adopted by Learning Management System (LMS) vendors and educational technology providers.

Digital Education Strategies (2019a) introduced the term “curb-cut effect” within the context of accessible web design. This concept illustrates how features such as video captioning not only support individuals with permanent disabilities but also benefit English as a Second Language (ESL) learners, users experiencing situational limitations (e.g., nurses working in noisy clinical environments), and even contribute to improved search engine optimization. In their subsequent publication, Digital Education Strategies (2019b) reframed accessibility through a strategic lens, by positioning it as both a form of risk mitigation and an avenue for market growth. This business-oriented perspective has been widely adopted by Learning Management System (LMS) vendors and educational technology providers.

Media Narratives and Pandemic Insights

A 2020 CBC segment on virtual learning and disability highlighted several critical accessibility failures within online education. These included the absence of real-time captioning, reliance on inaccessible PDF handouts, and the use of proctored testing platforms that were incompatible with screen readers. Students reported experiencing emotional exhaustion from the constant need to self-advocate and described a decline in academic performance. Collectively, these accounts point to systemic shortcomings in the design and delivery of accessible digital learning environments.

A 2020 CBC segment on virtual learning and disability highlighted several critical accessibility failures within online education. These included the absence of real-time captioning, reliance on inaccessible PDF handouts, and the use of proctored testing platforms that were incompatible with screen readers. Students reported experiencing emotional exhaustion from the constant need to self-advocate and described a decline in academic performance. Collectively, these accounts point to systemic shortcomings in the design and delivery of accessible digital learning environments.

Limitations in Current Research

Existing scholarship reveals a significant gap in large-scale, discipline-specific research exploring the application and outcomes of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) within nursing education. Much of the current literature tends to treat students with disabilities as a monolithic group, which obscures the need for more targeted, cognitive-specific instructional strategies. Additionally, return-on-investment analyses in this area rarely extend to include long-term patient care outcomes that may result from improved educational accessibility. This paper seeks to address these limitations by examining cognitive diversity within nursing cohorts and articulating the connection between inclusive educational design and clinical safety outcomes.

Existing scholarship reveals a significant gap in large-scale, discipline-specific research exploring the application and outcomes of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) within nursing education. Much of the current literature tends to treat students with disabilities as a monolithic group, which obscures the need for more targeted, cognitive-specific instructional strategies. Additionally, return-on-investment analyses in this area rarely extend to include long-term patient care outcomes that may result from improved educational accessibility. This paper seeks to address these limitations by examining cognitive diversity within nursing cohorts and articulating the connection between inclusive educational design and clinical safety outcomes.

Problem Analysis: Cognitive Barriers in Nursing Education

- Information Overload – Pharmacology textbooks can exceed one thousand pages; lecture slide decks can top one hundred slides. Students with working memory limitations often struggle to distinguish relevant information from background distractions.

- Abstract Conceptualization – Biochemical cascades, fluid and electrolyte balance, and complex pathophysiological feedback can place significant demands on a student’s cognitive processing and spatial reasoning skills. In the absence of concrete analogies or representations, conceptual gaps will widen over time.

- Attention Regulation – Lengthy monologues and traditional slide decks offer limited access pathways for learners with ADHD. The constant need to alternate focus during a hospital shift work contributes to a decline in sustained attention and concentration.

- Processing Speed – Timed dosage-calculation quizzes may disadvantage learners who need methodical steps, not mental math. Responding to a rapidly deteriorating patient requires quick thinking, assessment, recall, and troubleshooting. This limits the ability of the nurse to stop, focus, think strategically, and plan.

- Executive Function and Organization – Multi-step care plans require sequencing, prioritization, and synthesis. These skills make nurses susceptible to executive function disruption.

- Stigma and Non-Disclosure – Clinical culture often reinforces expectations of resilience, frequently referred to as having “thick skin.” Within this context, some nursing students may fear that requesting accommodations could be perceived as a sign of incompetence. This concern may contribute to stigma, increase the risk of clinical placement rejections, and expose learners to judgment from peers and supervisors.

Digital learning environments can intensify accessibility barriers, particularly when instructional videos lack captions or when required readings are presented as scanned PDFs, which are often incompatible with screen readers. These challenges are further exacerbated when course policies, such as strict deadlines for discussion posts, fail to accommodate learners with variable processing speeds. Such barriers are not isolated technical oversights: rather, they reflect systemic design flaws that span content delivery, pedagogical strategy, and assessment practices.

Instructional Design Solutions and Digital Resources

Scaffolding and Chunking

Structuring instructional modules into 10–15-minute micro-lessons with clearly defined learning outcomes can effectively reduce cognitive load and enhance learner focus. Embedding “pause and predict” prompts within video content helps activate prior knowledge and maintain engagement throughout the lesson. In the context of medication calculations, instructional strategies should emphasize step-by-step demonstrations of mathematical processes. Visualizing each stage of dosage calculation, rather than presenting only the final answer, supports deeper comprehension and skill retention, particularly for learners with cognitive processing differences.

Structuring instructional modules into 10–15-minute micro-lessons with clearly defined learning outcomes can effectively reduce cognitive load and enhance learner focus. Embedding “pause and predict” prompts within video content helps activate prior knowledge and maintain engagement throughout the lesson. In the context of medication calculations, instructional strategies should emphasize step-by-step demonstrations of mathematical processes. Visualizing each stage of dosage calculation, rather than presenting only the final answer, supports deeper comprehension and skill retention, particularly for learners with cognitive processing differences.

Multimodal Representation

- 3-D Anatomy Apps – Tools such as Complete Anatomy (3D4Medical Ltd., 2025) allow rotation and layering of organ systems, benefiting spatial learners.

- Interactive Timelines – Mapping disease progression enhances temporal reasoning.

- Captioned/Narrated Slides – Berman’s (2014) advocacy stresses that captions aid retention for everyone; nursing jargon is spelled out, assisting ESL learners and dyslexic readers.

Flexible Assessment

Options include:

- Recording a screencast that walks through a pharmacokinetic diagram.

- Building a concept map linking lab values to interventions.

- Performing a high-fidelity simulation scored via a rubric.

- Emphasizing clinical reasoning over syntactic accuracy helps to reduce potential bias towards students with dyslexia.

Adaptive Learning Technologies

Adaptive learning platforms that dynamically adjust quiz difficulty based on student performance can offer personalized practice by targeting areas of weakness. For nursing students, this individualized approach enhances skill development and knowledge retention. Additionally, virtual simulations that feature branching scenarios offer learners the opportunity to explore multiple decision pathways. When incorrect choices result in immediate, explanatory feedback, students benefit from repeated, low-stakes practice in a safe and supportive environment. This structure promotes deeper clinical reasoning and enhances the transfer of theoretical knowledge to practice.

Adaptive learning platforms that dynamically adjust quiz difficulty based on student performance can offer personalized practice by targeting areas of weakness. For nursing students, this individualized approach enhances skill development and knowledge retention. Additionally, virtual simulations that feature branching scenarios offer learners the opportunity to explore multiple decision pathways. When incorrect choices result in immediate, explanatory feedback, students benefit from repeated, low-stakes practice in a safe and supportive environment. This structure promotes deeper clinical reasoning and enhances the transfer of theoretical knowledge to practice.

Collaborative & Reflective Tools

Collaborative tools such as Google Workspace (n.d.) facilitate peer editing through tracked changes, promoting accountability and shared learning. Platforms like VoiceThread enhance asynchronous interaction by allowing students to contribute through text, audio, or video, thereby supporting diverse communication preferences. Additionally, multimodal self-reflection journals, whether typed, voice-recorded, or image-based, foster metacognitive awareness, a critical component of lifelong learning and professional growth.

Collaborative tools such as Google Workspace (n.d.) facilitate peer editing through tracked changes, promoting accountability and shared learning. Platforms like VoiceThread enhance asynchronous interaction by allowing students to contribute through text, audio, or video, thereby supporting diverse communication preferences. Additionally, multimodal self-reflection journals, whether typed, voice-recorded, or image-based, foster metacognitive awareness, a critical component of lifelong learning and professional growth.

Case Studies

Community Hospital Digital Orientation

Following an AODA compliance audit, it was discovered that many orientation videos lacked closed captions and that most quizzes were set to time out after thirty minutes without the ability to pause. This created significant accessibility barriers. In response, the hospital recognized the urgent need to enhance content accessibility and partnered with an instructional design team to ensure that all learning materials were inclusive and supportive of diverse staff and learner needs. Revisions such as these should include:

Following an AODA compliance audit, it was discovered that many orientation videos lacked closed captions and that most quizzes were set to time out after thirty minutes without the ability to pause. This created significant accessibility barriers. In response, the hospital recognized the urgent need to enhance content accessibility and partnered with an instructional design team to ensure that all learning materials were inclusive and supportive of diverse staff and learner needs. Revisions such as these should include:

- WCAG-compliant HTML5 modules with alt-text and keyboard navigation.

- Captions plus downloadable transcripts in plain language.

- Branching decision trees simulating a code-blue response.

- Learner satisfaction

- Improved retention among new nurses.

- Zero AODA violations in the follow-up audit.

Online BSN Program Redesign

A private university transitioned its core Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BScN) curriculum to a Learning Management System (LMS) grounded in Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles. Key enhancements that should be implemented during this migration include:

A private university transitioned its core Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BScN) curriculum to a Learning Management System (LMS) grounded in Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles. Key enhancements that should be implemented during this migration include:

- Weekly “choose your path” activities: discussion board, infographic creation, or case study reflection.

- Gamified pharmacology quizzes using spaced repetition flashcards.

- Optional live “ask me anything” sessions recorded and captioned.

- Outcome data are revealed and examined

- Pharmacology exam scores increased.

- Accommodation requests for extended test time dropped.

- Students citing a disability in exit surveys increased, indicating greater disclosure comfort.

Implementation Challenges

- Budgetary Constraints – High-fidelity simulation and AR/VR require significant upfront investment that leadership may refuse without return-on-investment data.

- Faculty Workload – Redesigning a course for UDL can require up to one hundred hours to create. Release time and stipends serve as effective strategies to reduce burnout by offering both time and financial recognition.

- Legacy Infrastructure – Older LMSs may lack built-in accessibility checkers, necessitating third-party tools.

- Digital Divide – Rural learners or night-shift nurses may have limited bandwidth; therefore, offline accommodations are needed.

- Cultural Resistance – Some clinicians mistakenly equate accommodations with lowered standards and expectations, rather than recognizing them as tools for equitable access. Evidence-based professional development workshops can reframe accessibility as safety and quality.

Policy Recommendations

- Mandatory WCAG Audits – Annual third-party evaluations flag issues before litigation or compliance fines.

- Accessibility Champions – Designate faculty liaisons in each program to mentor peers and liaise with IT.

- UDL-Aligned Curriculum Approval – New courses must document how they meet MMR, MMAE, and MME.

- Accreditation Criteria – Professional bodies (e.g., College of Nurses of Ontario, Canadian Nursing Association) should require evidence of accessible design.

- Performance Incentives – Base departmental funding on the ability to demonstrate accessibility improvements.

- Learner Co-Design Panels – Include students with disabilities in tool pilots and syllabus reviews.

Conclusion

Cognitive accessibility is not an optional add-on; it is a prerequisite for ethical, effective nursing education and safe clinical practice. By embracing Universal Design for Learning and thoughtfully leveraging digital tools, educators can dismantle barriers that have long impeded adult learners with cognitive disabilities. The evidence is clear that multimodal representation enhances comprehension, flexible assessments capture authentic competence, and accessible technology benefits all users. Institutions that invest in these strategies observe higher retention, improved licensure outcomes, and reduced liability.

This roadmap offers a design rooted in empirical research, case studies, practical policy mechanisms, and operational solutions. It invites stakeholders to move beyond compliance toward genuine inclusion. Doing this will ensure alignment in nursing education across post-secondary education as well as workplace settings. An organization’s commitment to prioritizing equitable and empowered learning experiences for future clinicians reinforces the foundational ethic of care that they expect to be upheld in practice.

References

3D4Medical Ltd. (2025). Complete Anatomy. https://3d4medical.com/

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.).

Bain de Los Santos, S., Kupczynski, L., & Mundy, M. (2019). Determining academic success in students with disabilities in higher education. International Journal of Higher Education, 8(2), 16–38. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1212595.pdf

Berman, D. (2014, May 13). Web accessibility matters: Why should we care [Video]. https://youtu.be/VIRx3RJzbZg

Brandon University. (n.d.). Obstacles in nursing education: The stories of students who experience disabilities. https://www.brandonu.ca/research-connection

CBC News: The National. (2020, December 3). Students with learning disabilities face additional virtual learning challenges [Video]. https://youtu.be/zDSHHB0ckYQ

CAST. (2024). Universal Design for Learning guidelines version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Chiu, Y., Hsiao-Ying, V., Johnston, A., Herbert, J., & Niu, X. (2019). Impact of disability services on academic achievement among college students with disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 32(3), 227–245. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1236854.pdf

D’Angelo, C. (2018). The impacts of technology integration. In R. Power (Ed.), Technology and the curriculum: Summer 2018. Power Learning Solutions. https://pressbooks.pub/techandcurriculum/chapter/engagement-and-success/

Digital Education Strategies, The Chang School. (2019a). The “curb cut” effect: An accessible web benefits all. In Introduction to web accessibility: Essential accessibility for everyone. Toronto Metropolitan University. https://pressbooks.library.torontomu.ca/iwacc/chapter/curb-cuts/

Digital Education Strategies, The Chang School. (2019b). The business case for web accessibility. In Introduction to web accessibility: Essential accessibility for everyone. Toronto Metropolitan University. https://pressbooks.library.torontomu.ca/iwacc/chapter/thebusiness-case-for-web-accessibility/

D2L. (2024). Accessible education: The complete guide. https://www.d2l.com/blog/accessible-education-the-complete-guide/

Enable Education. (2025). Enhancing educational equity: Strategies for accessibility in learning. https://www.enableeducation.com/the-learning-curve/strategies-for-accessibility-inlearning

Google (n.d.). Google Workspace: How teams of all sizes connect, create, and collaborate. https://workspace.google.com/intl/en_ca/

McGinty, T. (2018). Tips for creating inclusive and accessible instruction for adult learners. PAACE Journal of Lifelong Learning, 27, 1–19.

NursingEducation.org. (2024). Resources for nursing students with disabilities. https://nursingeducation.org/resources/nursing-students-with-disabilities/

Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2016). Policy on accessible education for students with disabilities. https://www.ohrc.on.ca

Timmerman, L., & Mulvihill, T. (2015). Self-disclosure of disability among university students: A review of literature and practice. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 28(3), 361–372.

University of Guelph. (n.d.). Universal instructional design and Universal Design for Learning. https://otl.uoguelph.ca

W3C (2025). Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). [Web page]. https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/wcag/