Equity in Language Instruction: Addressing the Barriers for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Learners in K-12 Education

Fay Broyt and Gabriel D'Ugo

Introduction

![]() Deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH) students face persistent and multifaceted barriers in language-rich educational contexts such as English Language Arts and French as a Second Language (FSL). The language curricula of Ontario’s K-12 public education system, particularly for English and FSL, have their roots in oral-aural communication and place a strong emphasis on auditory-based evaluation, spoken language, and listening comprehension. Children whose primary mode of communication is not spoken language face significant and persistent structural disadvantages due to these curriculum expectations (Kang & Scott, 2021; Csizér & Kontra, 2020; Olszak & Borowicz, 2025). Although there has been a legal and ethical push for inclusion with the implementation of the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) in 2005 and increased global awareness of differentiated learning, the implementation of accessible practices in language instruction remains inconsistent and insufficient to meet DHH students’ needs (Power, 2024; Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024).

Deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH) students face persistent and multifaceted barriers in language-rich educational contexts such as English Language Arts and French as a Second Language (FSL). The language curricula of Ontario’s K-12 public education system, particularly for English and FSL, have their roots in oral-aural communication and place a strong emphasis on auditory-based evaluation, spoken language, and listening comprehension. Children whose primary mode of communication is not spoken language face significant and persistent structural disadvantages due to these curriculum expectations (Kang & Scott, 2021; Csizér & Kontra, 2020; Olszak & Borowicz, 2025). Although there has been a legal and ethical push for inclusion with the implementation of the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) in 2005 and increased global awareness of differentiated learning, the implementation of accessible practices in language instruction remains inconsistent and insufficient to meet DHH students’ needs (Power, 2024; Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024).

Despite legislative mandates, many DHH students are still taught using materials and methods that were created for hearing students. This has led to such students’ disengagement, decreased motivation, and restricted access to the language acquisition opportunities that their peers enjoy (Kang & Scott, 2021; Csizér & Kontra, 2020; Dale & Neild, 2023). Focusing on English and FSL instruction, this paper critically analyzes the various, interconnected challenges that DHH children encounter in Ontario’s K-12 language learning contexts. It outlines the instructional design strategies and digital solutions that can support equity in language learning by drawing on Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles and research on accessible pedagogy and technology. To support DHH learners’ right to complete and meaningful engagement with language education, it is necessary to highlight inclusive, evidence-based approaches that address their linguistic, cultural, and emotional needs (Power, 2024; Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2025).

Barriers to Accessible Language Learning

![]() In language classrooms, DHH students encounter various interconnected obstacles in accessing, comprehending, and effectively producing language. First, and the most enduring, is the use of spoken dialogue and auditory instruction in both English and French language classes. DHH children are disadvantaged by traditional classroom methods, curriculum expectations, and assessment frameworks that frequently emphasize speaking and listening abilities rather than reading and writing (Kang & Scott, 2021; Csizér & Kontra, 2020). Currently, most instructional resources and activities are tailored to hearing students, even when schools implement differentiated learning strategies. Consequently, DHH students may feel alienated during classroom interactions (Olszak & Borowicz, 2025; Csizér & Kontra, 2020).

In language classrooms, DHH students encounter various interconnected obstacles in accessing, comprehending, and effectively producing language. First, and the most enduring, is the use of spoken dialogue and auditory instruction in both English and French language classes. DHH children are disadvantaged by traditional classroom methods, curriculum expectations, and assessment frameworks that frequently emphasize speaking and listening abilities rather than reading and writing (Kang & Scott, 2021; Csizér & Kontra, 2020). Currently, most instructional resources and activities are tailored to hearing students, even when schools implement differentiated learning strategies. Consequently, DHH students may feel alienated during classroom interactions (Olszak & Borowicz, 2025; Csizér & Kontra, 2020).

Second, the lack of sufficient visual aids greatly contributes to these difficulties. DHH students might struggle to follow or participate in real time when instructional materials such as videos and multimedia presentations are used without proper captioning or sign language interpretation (Chen et al., 2025; Talaván, 2019; Gehret & Elliot, 2025). Moreover, automated captioning tools can misrepresent spoken content and lead to misunderstandings or false information (Talaván, 2019; Gehret & Elliot, 2025). These technical issues directly impair DHH students’ language understanding and engagement, leading to frustration and less effective instruction (Talaván, 2019).

Third, DHH students are frequently at a disadvantage in terms of assessment. Standardized language tests typically rely on verbal understanding and auditory comprehension, particularly in oral-heavy courses such as FSL. DHH children may not always be able to access these skills due to their limited or no exposure to spoken language (Dale & Neild, 2023; Kang & Scott, 2021). Consequently, these tests do not fairly represent their language skills or learning potential. Instead, they may impact the students’ self-esteem, reinforce poor academic self-perceptions, or even result in unjustified exclusion from crucial educational opportunities (Kang & Scott, 2021; Olszak & Borowicz, 2025).

The fourth gap is educators’ professional development (PD). Many educators have expressed a lack of readiness to modify resources or implement inclusive teaching practices that cater to DHH students’ requirements (Power, 2024; Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024). Limited professional development can cause teachers to fall back on tried-and-true, auditory-based teaching methods or depend on resources that are not easily accessible (Power, 2024; Gehret & Elliot, 2025). The lack of tailored services such as captioning software, assistive technology, and classroom management strategies further contributes to the disconnect between the educator and DHH students.

The fifth gap includes structural and cultural obstacles. DHH learners are diverse, with different levels of hearing loss, various linguistic backgrounds (such as spoken languages, American Sign Language, ASL; Langue des signes Québécoise, LSQ), and access to assistive technology (Dale & Neild, 2023). However, classroom instruction and resource distribution typically employ the one-size-fits-all approach, often ignoring the differentiated support needed for effective engagement of all students (Dale & Neild, 2023; Csizér & Kontra, 2020). For instance, students have reported feeling excluded from group activities and classroom discussions and unable to properly express their language talents due to the lack of relevant accommodations (such as real-time captioning, sign language interpretation, visual aids, extended processing time, or alternative oral participation formats), leading to feelings of alienation and disconnect from their classroom and school communities (Csizér & Kontra, 2020).

Finally, Ontario’s requirements for FSL education from grades 4 to 9 further complicate access for DHH students. They are required to learn oral French by speaking and listening, which exacerbates existing disparities and lowers academic motivation. They must also learn a second spoken language in a way not compatible with their primary communication style; this could result in program withdrawal if there is insufficient visual scaffolding or alternative assessments (Olszak & Borowicz, 2025; Kang & Scott, 2021). Furthermore, DHH students are often exempt from FSL due to a lack of suitable accommodations, which restricts their future academic, social, and career options (Kang & Scott, 2021; Olszak & Borowicz, 2025).

Theoretical Framework: Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

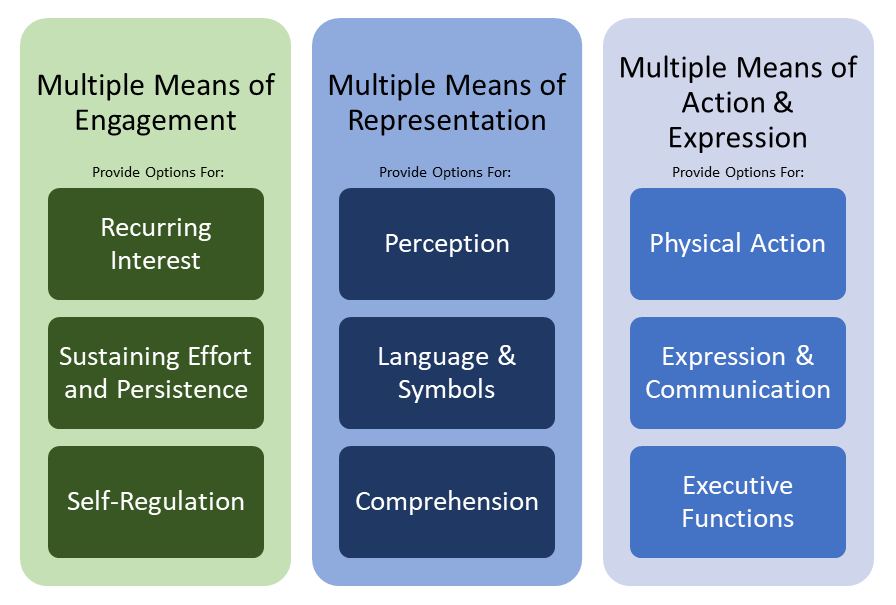

Universal Design for Learning (UDL), originally developed in the 1990s by researchers at the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST), is a flexible, research-based framework developed to reduce barriers and promote inclusive education (CAST, 2018). UDL has since been adapted to rethink language education to be more inclusive of DHH learners. Its foundation is the knowledge that every learner is unique in their approach to content engagement, information processing, and knowledge expression. According to Power (2024) and Marcus-Quinn et al. (2024), the three core principles of engagement, representation, and action/expression via multiple means enable educators to design learning experiences that intentionally address diverse learner preferences, strengths, and needs.

For DHH students, UDL application entails intentionally incorporating multimodal resources that promote visual, spatial, and kinesthetic learning while transitioning away from an auditory-centric model. For instance, educators can use visual glossaries, sign language videos, captioned media, written instructions, and other graphic supports to make content accessible (Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024; Olszak & Borowicz, 2025; Gehret & Elliot, 2025). Additionally, UDL principles encourage providing students with options for how to display their learning. To acknowledge and validate their varied communication abilities, methods such as multimedia presentations, written narratives, visual storyboards, or video reflections must be included (Chen et al., 2025; Csizér & Kontra, 2020).

However, promoting learner autonomy and emotional engagement is an important but frequently overlooked aspect of UDL. Since DHH students might feel more stressed or disengaged in inaccessible learning situations, it is important to encourage self-regulated learning and emotional awareness (Chen et al., 2025; Csizér & Kontra, 2020). Motivation, resilience, and a positive academic identity can be enhanced using resources and instructional strategies that promote self-reflection, peer review, and emotional check-ins (Chen et al., 2025; Csizér & Kontra, 2020).

Instructional Design Strategies for Inclusion

UDL implementation in language classes requires a conscious move toward visually rich, student-centered, and accessible teaching methods that meet DHH learners’ demands. Research has highlighted various evidence-based strategies that, when regularly used, can greatly increase DHH students’ success and involvement in language learning environments.

Visual Scaffolding Tools

For abstract linguistic concepts, visual aids such as mind maps, pictorial dictionaries, illustrated grammar explanations, and graphic organizers offer crucial context. These resources promote deeper comprehension and retention by helping DHH students draw connections between previously learned material, new vocabulary, and grammatical structures (Olszak & Borowicz, 2025; Gehret & Elliot, 2025). Additionally, for those who might not receive significant auditory input, visual scaffolds help make language acquisition more tangible and approachable.

For abstract linguistic concepts, visual aids such as mind maps, pictorial dictionaries, illustrated grammar explanations, and graphic organizers offer crucial context. These resources promote deeper comprehension and retention by helping DHH students draw connections between previously learned material, new vocabulary, and grammatical structures (Olszak & Borowicz, 2025; Gehret & Elliot, 2025). Additionally, for those who might not receive significant auditory input, visual scaffolds help make language acquisition more tangible and approachable.

Balancing Modalities

Numerous studies have advised rebalancing the emphasis between oral and written modalities. Accordingly, instruction should focus on reading and writing tasks that are more in line with the preferences and strengths of DHH learners rather than with speaking and listening as the sole criterion for proficiency (Kang & Scott, 2021; Gehret & Elliot, 2025). To improve understanding and produce easily accessible reference resources, written dialogue transcripts, instructional summaries, and vocabulary banks must be used (Power, 2024; Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024).

Numerous studies have advised rebalancing the emphasis between oral and written modalities. Accordingly, instruction should focus on reading and writing tasks that are more in line with the preferences and strengths of DHH learners rather than with speaking and listening as the sole criterion for proficiency (Kang & Scott, 2021; Gehret & Elliot, 2025). To improve understanding and produce easily accessible reference resources, written dialogue transcripts, instructional summaries, and vocabulary banks must be used (Power, 2024; Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024).

Student-Generated Content

Having students co-design multimedia presentations or make their own subtitles for videos (i.e., subtitles for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing or SDH) is a creative and highly successful approach. According to Talaván (2019), the active process of creating subtitles improves lexical creativity, written production, and listening comprehension (to the extent possible). It also offers authentic opportunities for project-based and collaborative learning. Seeing their identities and experiences represented in the learning process fosters students’ cultural responsiveness, digital literacy, and ownership (Talaván, 2019; Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024).

Having students co-design multimedia presentations or make their own subtitles for videos (i.e., subtitles for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing or SDH) is a creative and highly successful approach. According to Talaván (2019), the active process of creating subtitles improves lexical creativity, written production, and listening comprehension (to the extent possible). It also offers authentic opportunities for project-based and collaborative learning. Seeing their identities and experiences represented in the learning process fosters students’ cultural responsiveness, digital literacy, and ownership (Talaván, 2019; Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024).

Explicit Instruction in Learning Strategies

By explicitly teaching metacognitive practices such as self-monitoring and using comprehension checks and digital organizers, teachers may empower DHH students. Tools, including self-reflection journals, checklists, and structured peer feedback, help students not only identify when their comprehension is failing but also find the right resources (Csizér & Kontra, 2020; Olszak & Borowicz, 2025).

By explicitly teaching metacognitive practices such as self-monitoring and using comprehension checks and digital organizers, teachers may empower DHH students. Tools, including self-reflection journals, checklists, and structured peer feedback, help students not only identify when their comprehension is failing but also find the right resources (Csizér & Kontra, 2020; Olszak & Borowicz, 2025).

Collaborative and Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

![]() To encourage belonging and engagement, teachers must implement collaborative teaching strategies such as small group work, peer tutoring, and co-construction of meaning through gesture, written materials, and visual signals. This is particularly crucial for multilingual or multicultural learners, as culturally responsive techniques acknowledge and appreciate DHH students’ linguistic and cultural backgrounds (Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024; Csizér & Kontra, 2020).

To encourage belonging and engagement, teachers must implement collaborative teaching strategies such as small group work, peer tutoring, and co-construction of meaning through gesture, written materials, and visual signals. This is particularly crucial for multilingual or multicultural learners, as culturally responsive techniques acknowledge and appreciate DHH students’ linguistic and cultural backgrounds (Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024; Csizér & Kontra, 2020).

Digital Resource Solutions

An essential element in providing DHH learners with equitable language instruction is the incorporation of digital tools and accessible technologies. When carefully chosen and utilized, digital resources may turn passive learning experiences into accessible, dynamic, and captivating learning environments for every student.

Accurate Captioning and Sign Language Integration

Captioned videos are most effective when the captions are accurate, properly synchronized, and supported by sign language interpretation when available (Power, 2024; Gehret & Elliot, 2025). Although they are commonly used, automated captions need to be thoroughly examined and updated to prevent spreading false information or misconceptions (Talaván, 2019). For students who primarily use sign language, incorporating it alongside text or images in digital content ensures accessibility (Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024).

Captioned videos are most effective when the captions are accurate, properly synchronized, and supported by sign language interpretation when available (Power, 2024; Gehret & Elliot, 2025). Although they are commonly used, automated captions need to be thoroughly examined and updated to prevent spreading false information or misconceptions (Talaván, 2019). For students who primarily use sign language, incorporating it alongside text or images in digital content ensures accessibility (Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024).

Emotion Recognition and Reflective Tools

Emerging technologies such as self-reporting interfaces and automatic emotion recognition (AER) can improve emotional regulation and self-awareness among DHH learners (Chen et al., 2025). By integrating these tools into video-based learning settings, students may monitor their progress, use prior knowledge, and seek specialized help. However, such technologies should be used keeping in mind the cultural and privacy issues and to complement, not substitute, human connection (Chen et al., 2025).

Emerging technologies such as self-reporting interfaces and automatic emotion recognition (AER) can improve emotional regulation and self-awareness among DHH learners (Chen et al., 2025). By integrating these tools into video-based learning settings, students may monitor their progress, use prior knowledge, and seek specialized help. However, such technologies should be used keeping in mind the cultural and privacy issues and to complement, not substitute, human connection (Chen et al., 2025).

Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning (CTML)

Asynchronous e-learning tutorials created using cognitive theory of multimedia learning (CTML) principles, which include breaking up the knowledge into manageable chunks, offering unambiguous visual cues, and allowing customized pacing, can improve DHH students’ comprehension (Gehret & Elliot, 2025). Signalling (highlighting important information) and tailored pacing enable them to evaluate content at their own pace while segmenting lessens cognitive overload. Platforms such as Canva for Education and EDpuzzle provide flexible environments for incorporating these ideas into flipped or blended classroom formats (Power, 2024; Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024).

Asynchronous e-learning tutorials created using cognitive theory of multimedia learning (CTML) principles, which include breaking up the knowledge into manageable chunks, offering unambiguous visual cues, and allowing customized pacing, can improve DHH students’ comprehension (Gehret & Elliot, 2025). Signalling (highlighting important information) and tailored pacing enable them to evaluate content at their own pace while segmenting lessens cognitive overload. Platforms such as Canva for Education and EDpuzzle provide flexible environments for incorporating these ideas into flipped or blended classroom formats (Power, 2024; Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024).

Subtitling Projects and Peer-Based Learning

![]() Digital literacy can be developed and inclusive classroom cultures promoted through assignments where students work together to edit and add subtitles or co-create accessible multimedia resources (Talaván, 2019). By allowing DHH students to be active participants rather than just users of accommodations, these strategies go beyond deficit-based models (Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024).

Digital literacy can be developed and inclusive classroom cultures promoted through assignments where students work together to edit and add subtitles or co-create accessible multimedia resources (Talaván, 2019). By allowing DHH students to be active participants rather than just users of accommodations, these strategies go beyond deficit-based models (Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024).

Implications for Ontario K-12 Language Programs

Fair access to language education for DHH children must become a primary concern at all levels of policy making and practice in Ontario’s education system, particularly since language instruction is fundamental and FSL is a required subject at many grade levels (Kang & Scott, 2021). Accordingly, school boards should ensure that digital solutions and accessible teaching methods are incorporated into curriculum guidelines and teachers receive ongoing professional development (Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024; Csizér & Kontra, 2020), including the following:

Fair access to language education for DHH children must become a primary concern at all levels of policy making and practice in Ontario’s education system, particularly since language instruction is fundamental and FSL is a required subject at many grade levels (Kang & Scott, 2021). Accordingly, school boards should ensure that digital solutions and accessible teaching methods are incorporated into curriculum guidelines and teachers receive ongoing professional development (Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024; Csizér & Kontra, 2020), including the following:

- Regular training for educators on UDL, accessible captioning, and the integration of sign language resources (Power, 2024; Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024)

- Investment in co-teaching models involving Deaf educators and provision of communication support professionals (CSPs) or ASL/LSQ interpreters (Dale & Neild, 2023)

- Curriculum flexibility that allows DHH students to demonstrate proficiency through visual or written means, rather than relying exclusively on oral assessments (Dale & Neild, 2023; Kang & Scott, 2021)

- Exploration and, where possible, inclusion of Indigenous or regional sign languages in the curriculum to affirm all students’ cultural and linguistic identities (Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024)

- Collaboration with Deaf educators, interpreters, and DHH students to co-design and evaluate responsive programs (Power, 2024; Csizér & Kontra, 2020)

- Centralized, accessible resource databases curated by the Ministry of Education and school boards to support inclusive classroom practice (Power, 2024)

Overall, closing the accessibility gap and promoting long-term inclusion for DHH learners in Ontario’s language classrooms requires a multi-tiered strategy that integrates policy, practice, and stakeholder involvement (Kang & Scott, 2021; Power, 2024).

Conclusion

Achieving equity in language instruction for DHH students requires a shift from retrofitted accommodations to proactive, inclusive design (Power, 2024; Chen et al., 2025; Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024). Accessibility and inclusion must be prioritized from program design to achieve equity in language instruction for such students. Schools in Ontario can establish language learning environments that assist all students in gaining literacy, communication, and confidence by implementing UDL principles, utilizing digital and multimedia resources, and encouraging ongoing professional development for teachers (Marcus-Quinn et al., 2024; Gehret & Elliot, 2025).

To meet the legal and ethical requirements as well as ensure every student’s right to complete and meaningful involvement in language instruction, a sustained commitment to these approaches is required. The current teaching methods and educators’ understanding of accessibility must change through constant self-reflection, teamwork, and creativity. Every student, regardless of their hearing ability, can flourish and make a significant contribution to their communities in an educational system that is truly equitable. This is possible only when educators, administrators, and legislators actively pursue inclusive design and culturally responsive pedagogy.

References

Canva. (n.d.). Canva for education. https://www.canva.com/education/

CAST. (2018). Universal Design for Learning guidelines version 2.2. https://udlguidelines.cast.org

Chen, S., Situ, J., Cheng, H., Su, S., Kirst, D., Ming, L., Wang, Q., & Huang, Y. (2025).

Inclusive emotion technologies: Addressing the needs of d/Deaf and hard of hearing learners in video-based learning. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 9(2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1145/3711013

Csizér, K., & Kontra, E. H. (2020). Foreign language learning characteristics of deaf and severely hard-of-hearing students. The Modern Language Journal, 104(1), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12630

Dale, B. A., & Neild, R. (2023). Virtual assessment of deaf and hard of hearing students in the schools. American Annals of the Deaf, 168(3), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2023.a917248

Edpuzzle. (n.d.). Edpuzzle: Make any video your lesson. https://edpuzzle.com/

Gehret, A. U., & Elliot, L. B. (2025). Perceptions of e-learning by deaf and hard of hearing students using asynchronous multimedia tutorials. Educational Technology Research and Development. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-025-10476-z

Kang, K. Y., & Scott, J. A. (2021). The experiences of and teaching strategies for deaf and hard of hearing foreign language learners: A systematic review of the literature. American Annals of the Deaf, 165(5), 527–547. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27017300

Marcus-Quinn, A., Krejtz, K., & Duarte, C. (Eds.). (2024). Transforming media accessibility in Europe: Digital media, education and city space accessibility contexts. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-60049-4

Olszak, I., & Borowicz, A. (2025). Learning styles and strategies of D/deaf and hard of hearing students in foreign language acquisition–a research report. Frontiers in Education, 10, 1553031. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1553031

Power, R. (2024). The ALT Text: Accessible learning with technology. Power Learning Solutions. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

Talaván, N. (2019). Using subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing as an innovative pedagogical tool in the language class. International Journal of English Studies, 19(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.6018/ijes.338671