Implementing Universal Design for Learning to Support Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students in Online Higher Education

Tayler Setten

Introduction

![]() According to the Canadian Association of the Deaf (2015a), the term deaf is a medical term that refers to people who have little or no functional hearing. Those who are considered hard-of-hearing experience hearing loss ranging from mild to severe (Canadian Association of the Deaf, 2015b). For students who are deaf or hard-of-hearing (DHH), the quality and quantity of accessibility accommodations available to them have a direct impact on their academic experience and outcomes.

According to the Canadian Association of the Deaf (2015a), the term deaf is a medical term that refers to people who have little or no functional hearing. Those who are considered hard-of-hearing experience hearing loss ranging from mild to severe (Canadian Association of the Deaf, 2015b). For students who are deaf or hard-of-hearing (DHH), the quality and quantity of accessibility accommodations available to them have a direct impact on their academic experience and outcomes.

The Canadian Hearing Society (2002) reports that fewer than 3% of DHH individuals in Canada hold university degrees. Researchers Powell et al. (2014) argue that the reason for lower graduation rates is complex, with numerous factors negatively contributing to DHH students’ overall academic performance, participation, and sense of inclusion. While the shift to digital learning has created opportunities for greater inclusion, it has also introduced new challenges. Many post-secondary institutions struggle to keep pace with technological advancements that support accessibility due to limited budgets, lack of educator training, and general burnout in the sector (Karasewich, 2024). As a result, DHH students are often limited or excluded from the digital learning experience entirely.

Currently, there remains a significant gap in the availability of accessibility accommodations on digital learning platforms for DHH students. The responsibility for inclusion often falls on educators, which is why they must understand and apply inclusive instructional strategies that benefit all students, not just those with disabilities. Frameworks such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL), along with the integration of accessible tools such as captioning, transcripts, and visual aids, are critical to creating more inclusive and equitable online learning experiences.

Understanding Accessibility Challenges in Online Post-Secondary Education Classrooms

Many of the challenges DHH students face in traditional classroom settings have persisted or worsened in online learning environments. These technological challenges include limited access to sign language interpreters, the loss of essential visual cues, poor audio quality, and the absence of transcripts or captions for lectures (Aljedaani et al., 2023). These barriers often result in lower academic performance and contribute to social isolation and communication difficulties for DHH students (Sarkar & Ghosh, 2024).

Many of the challenges DHH students face in traditional classroom settings have persisted or worsened in online learning environments. These technological challenges include limited access to sign language interpreters, the loss of essential visual cues, poor audio quality, and the absence of transcripts or captions for lectures (Aljedaani et al., 2023). These barriers often result in lower academic performance and contribute to social isolation and communication difficulties for DHH students (Sarkar & Ghosh, 2024).

One study examining the impact of technology-related challenges in deaf education during COVID-19 found that synchronous video conferencing was particularly difficult for DHH students, especially when multiple signers were involved or when real-time interpretation was unavailable (Aljedaani et al., 2023). In addition, communication delays were common, particularly during classroom discussions where students asked questions using sign language and had to wait for translation. As a result of these technological and instructional gaps, many DHH students reported feeling disengaged from their courses and resorted to playing video games during lessons due to their inability to fully access and engage with the content (Aljedaani et al., 2023).

Many accessibility guidelines in post-secondary education are guided by the Accessible Canada Act (“the Act”), a federal law that identifies, removes, and prevents barriers to access for people with disabilities. The Act was adopted in 2019 to create a barrier-free country by 2040 (About an Accessible Canada, 2025). While post-secondary institutions are not directly regulated by this law, the Act influences decision-making and has led to institution-wide accessibility plans that align with its goals. Many provinces have also adopted their own accessibility legislation, such as Ontario’s Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA), which was implemented in 2005. The AODA outlines five key standards for accessibility: customer service, employment, information and communication, transportation, and public spaces (About accessibility laws, 2025).

Despite these laws, DHH students continue to report lower graduation rates from post-secondary institutions, resulting in reduced employment opportunities among deaf communities (Garberoglio et al., 2019). The mandates intended to eliminate barriers have not yet closed these gaps or created enough equitable opportunities for DHH students to succeed (Garberoglio et al., 2020). As Garberoglio et al. (2020) explain, DHH students need more than quick fixes to persistent challenges—institutions must fully embed accessibility throughout the entire post-secondary education for DHH students to thrive.

Universal Design for Learning: A Framework for Inclusive Online Education

One way to address the barriers that DHH students continue to face is by introducing frameworks that naturally enhance educational access and engagement for all learners. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) (CAST, 2024) has emerged as a critical framework that is particularly relevant to DHH students. UDL aims to provide flexible learning options to better support a diversity of learners (Levesque et al., 2024). It considers students’ backgrounds, strengths, and preferences so every individual can thrive both academically and socially (Levesque et al., 2024). UDL also helps teachers identify barriers in their curriculum during the early stages of development (Taylor & Yuknis, 2023).

One way to address the barriers that DHH students continue to face is by introducing frameworks that naturally enhance educational access and engagement for all learners. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) (CAST, 2024) has emerged as a critical framework that is particularly relevant to DHH students. UDL aims to provide flexible learning options to better support a diversity of learners (Levesque et al., 2024). It considers students’ backgrounds, strengths, and preferences so every individual can thrive both academically and socially (Levesque et al., 2024). UDL also helps teachers identify barriers in their curriculum during the early stages of development (Taylor & Yuknis, 2023).

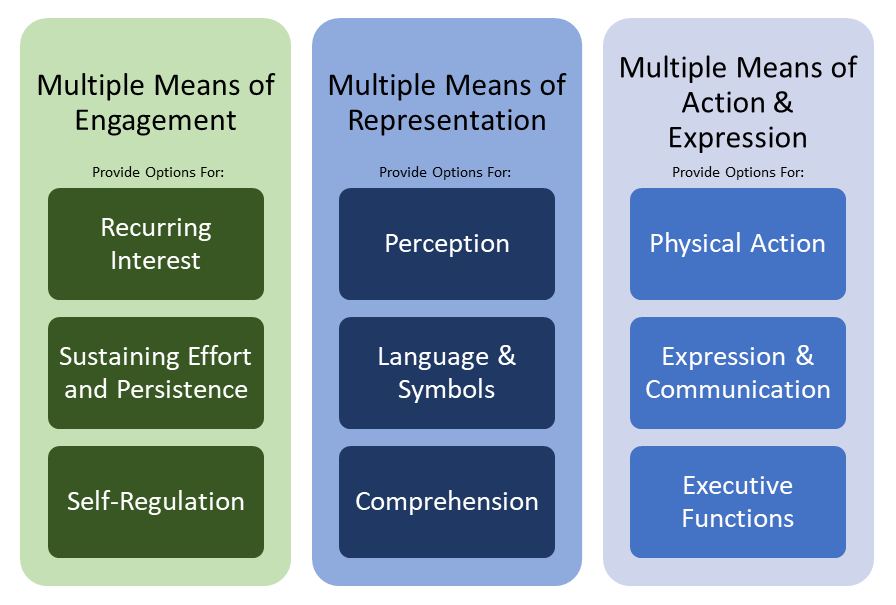

Grounded in neuroscience, UDL covers more than the physical aspects of the classroom and examines barriers within curriculum, instruction, and physical environments that influence a student’s interaction with learning (Taylor & Yuknis, 2023). UDL is guided by three main principles: multiple means of representation, multiple means of expression, and multiple means of engagement. These principles help guide educators to create inclusive learning environments that embrace the unique ways students learn, navigate, express, and engage with content (Levesque et al., 2024). UDL emphasizes building accessibility into the course design from the start, rather than adding it later. This approach is especially beneficial for DHH students and others with disabilities.

While UDL is a powerful tool for anticipating diverse students’ needs, some argue that the framework alone is not enough, particularly for deaf students. Weber et al. (2025) claim that “multiple means” is insufficient without intentional interactions designed specifically for deaf individuals, such as signed and tactile languages. The University of Alberta (n.d.) developed a guide that builds on UDL principles with targeted strategies that address barriers DHH students face in online higher education. These inclusive teaching strategies emphasize accessibility, flexibility, and student-centred learning. Key practices include using students’ primary languages (e.g., sign language or captions), incorporating multimodal teaching methods, and providing accessible video content. Instructors are encouraged to offer diverse forms of student expression, such as signed or multimedia assignments, and to integrate Deaf culture and experiences into the curriculum. Regular self-reflection and adaptation help ensure that these accommodations truly enhance learning (University of Alberta, n.d.). These approaches contribute to more inclusive environments that benefit all students.

A case study from the Australian Disability Clearinghouse on Education and Training (ADCET) illustrates the successful application of UDL for a physically challenged student and motorized wheelchair user. With support from his parents and James Cook University, a personalized digital learning environment was developed that included assistive technologies such as Apple devices and speech-to-text tools. This allowed the student to access learning flexibly across various environments and led to his recognition by Apple Singapore for his innovative use of technology (Australian Disability Clearinghouse on Education and Training, n.d.). The case highlights the importance of accessibility, flexibility, and leveraging students’ strengths when creating inclusive learning spaces.

Tools and Technology Available to Support UDL Implementation for Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students

![]() When applying UDL principles for DHH students, it is essential to integrate assistive technologies directly into lesson planning. Captioning benefits not only DHH students but also supports hearing students and English learners by improving concentration and accommodating diverse learning styles (Yabe, 2015). A study by Kmetz Morris et al. found that nearly 100% of students considered closed captioning helpful in online courses, even though only 7% identified as DHH (Adisa et al., 2019).

When applying UDL principles for DHH students, it is essential to integrate assistive technologies directly into lesson planning. Captioning benefits not only DHH students but also supports hearing students and English learners by improving concentration and accommodating diverse learning styles (Yabe, 2015). A study by Kmetz Morris et al. found that nearly 100% of students considered closed captioning helpful in online courses, even though only 7% identified as DHH (Adisa et al., 2019).

While automatic live captioning tools are improving and benefiting all students, they are still not fully reliable. Professional captioning services remain necessary for students who require accurate, real-time language access (Taylor & Yuknis, 2023). The Canadian Audiologist tested several voice-to-text applications for use in higher education and found that Microsoft Translator for PowerPoint (Microsoft, 2025) was the most effective (Adisa et al., 2019). This tool can display live subtitles on a PowerPoint slide or mobile device, with the option to save transcripts for later use. They found the application was fairly accurate, the only drawback being that, like most voice recognition software, it did not capture sound outside of dialogue; however, it is among the most promising applications to date and is a positive indicator for the potential of future technologies (Adisa et al., 2019).

Planning for accessibility from the start, such as incorporating closed captions and assistive listening devices, ensures that all students can engage with course materials simultaneously. Additionally, making tools like text-to-speech and word prediction software available to everyone should reduce stigma and support learners who need assistance but may not qualify for formal accommodations (Taylor & Yuknis, 2023).

Considerations and Concerns When Implementing UDL for DHH Students

Despite its many benefits, UDL implementation faces several challenges at both the instructor and institutional levels. A common barrier is the lack of adequate training and time for educators to plan flexible and inclusive materials (Scott, 2018). In addition, many instructors lack confidence in translating UDL theory into practical teaching strategies, particularly in online learning environments (Wahyuni et al., 2025). Lastly, institutional support remains limited. For example, in the U.S., fewer than half of post-secondary institutions allocate dedicated funds or resources to support UDL integration (Roberts et al., 2011). Without large-scale institutional commitment, in the form of ongoing professional development opportunities and suitable funding, UDL remains an individual approach taken by educators, rather than an institutional one. Research has demonstrated that successful implementation of UDL relies on embedding its principles into the curriculum design process from the beginning (Nelson & Bashman, 2014). To move beyond individual efforts, institutions must prioritize educator training, outline clear accessibility policies, and enhance cross-departmental collaboration (Wahyuni et al., 2025).

Despite its many benefits, UDL implementation faces several challenges at both the instructor and institutional levels. A common barrier is the lack of adequate training and time for educators to plan flexible and inclusive materials (Scott, 2018). In addition, many instructors lack confidence in translating UDL theory into practical teaching strategies, particularly in online learning environments (Wahyuni et al., 2025). Lastly, institutional support remains limited. For example, in the U.S., fewer than half of post-secondary institutions allocate dedicated funds or resources to support UDL integration (Roberts et al., 2011). Without large-scale institutional commitment, in the form of ongoing professional development opportunities and suitable funding, UDL remains an individual approach taken by educators, rather than an institutional one. Research has demonstrated that successful implementation of UDL relies on embedding its principles into the curriculum design process from the beginning (Nelson & Bashman, 2014). To move beyond individual efforts, institutions must prioritize educator training, outline clear accessibility policies, and enhance cross-departmental collaboration (Wahyuni et al., 2025).

Conclusion

Deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH) students continue to face systemic barriers in post-secondary education, particularly in digital learning environments. Although legislation such as the Accessible Canada Act and AODA has laid important groundwork for accessibility, many institutions still fall short in creating fully inclusive learning experiences. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) offers a powerful framework to anticipate and address diverse student needs, especially when paired with intentional strategies and assistive technologies tailored to DHH learners. Integrating accessibility features such as captioning, sign language interpretation, multimodal content, and personalized accommodations from the outset ensures that DHH students can access, engage with, and contribute to course content equitably. While challenges remain, particularly related to post-secondary training, resources, and infrastructure, investing in inclusive design is not only necessary for accessibility compliance but also essential for empowering all learners. Moving forward, sustained institutional commitment and educator support are critical to closing existing gaps and advancing accessibility in digital education.

References

About accessibility laws. (2025). Government of Ontario. https://www.ontario.ca/page/about-accessibility-laws

About an Accessible Canada. (2025). Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/accessible-canada.html

Adisa, S., Chow, V., Ciechanowski, S., Verge, J. (2019). The Use of Captions In Post-Secondary Institutions. Canadian Audiologist. https://canadianaudiologist.ca/the-use-of-captions-in-post-secondary-institutions/

Ajiedaani, W., Krasniqi, R., Aljedaani, S., Mkaouer, M.W., Ludi, S., & Al-Raddah, K. (2022). If online learning works for you, what about deaf students? Emerging challenges of online learning for deaf and hearing-impaired students during COVID-19: a literature review. Universal Access in the Information Society, 22(3), pp. 1027-1046. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-022-00897-5

Australian Disability Clearinghouse on Education and Training. (n.d.) UDL Case Studies. https://www.adcet.edu.au/inclusive-teaching/universal-design-for-learning/udl-resources/udl-case-studies

Canadian Association of the Deaf (2015a). Definition of “Deaf.” https://cad-asc.ca/issues-positions/definition-of-deaf/

Canadian Association of the Deaf. (2015b). Terminology. https://cad-asc.ca/issues-positions/terminology/

CAST (2024). The UDL guidelines. https://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Deaf & Hard-of-Hearing. (n.d.) Supporting Students with Disabilities. https://alc.ext.unb.ca/modules/deaf-and-hard-of-hearing/implications-for-learning.html

Garberoglio, C. L., Guerra, D. H., Sanders, G. T., Cawthon, S. W. (2020). Community-Driven Strategies for Improving Postsecondary Outcomes of deaf People. American Annals of the Deaf, 165(3), pp. 369–392. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2020.0024

Garberoglio, C. L., Palmer, J. L., Cawthon, S., & Sales, A. (2019). Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019. National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes. https://nationaldeafcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Deaf-People-and-Employment-in-the-United-States_-2019-7.26.19ENGLISHWEB.pdf

Karasewich, T.A. (2024). Accessibility in higher education. In M.E. Norris and S.M. Smith (Eds.), Leading the Way: Envisioning the Future of Higher Education. Queen’s University, eCampus Ontario. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/futureofhighereducation/chapter/accessibility-in-higher-education/

Kearney, D.B. (2022). Barriers to UDL Implementation. In Kearney, D.B. (Ed.) Universal Design for Learning (UDL) for Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility (IDEA). Creative Commons Attribution. https//www.saskoer.ca/universaldesign/

Levesque, E., Snoddon, K., Duncan, J. (2024). Universal design for learning: A pathway to independence for the deaf and hard of hearing learners. Deafness & Education, 26, pp. 299-300. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14643154.2024.2417500

Microsoft (2025). Presentation Translator for PowerPoint. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/translator/APPS/PRESENTATION-TRANSLATOR/

Nelson, L. L., & Basham, J. (2014). A Blueprint for UDL: Considering the Design of Implementation. Universal Design for Learning Implementation Network. https://simvilledev.ku.edu/sites/default/files/Video%20Resources/Open_UDL-IRN_Blueprint_V1.pdf

Powell, D., Hyde, M., & Punch, R. (2014). Inclusion in Postsecondary Institutions with Small Numbers of Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students: Highlights and Challenges. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 19(1), pp. 126–140. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/ent035

Roberts, K., Park, H., Brown, S., & Cook, B. (2011). Universal Design for Instruction in Postsecondary Education: A Systematic Review of Empirically Based Articles. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 24(1), pp. 5-15. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ941728.pdf

Sarkar, R., & Ghosh, A. (2024). Challenges faced by students with hearing impairment in higher education: A comprehensive analysis. International Journal of Speech and Audiology 5(1), pp. 6-12. https://doi.org/10.22271/27103846.2024.v5.i1a.43

Scott, L. A. (2018). Barriers With Implementing a Universal Design for Learning Framework. American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 6(4), pp. 274–286. https://doi.org/10.1352/2326-6988-6.4.274

Taylor, K., & Yuknis, C. (2023). Universal Design for Learning Supports Distance Learning for Deaf Students. American Annals of the Deaf, 168(3), pp. 41-54. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2023.a917249

The Canadian Hearing Society. (2002). Response of the Canadian Hearing Society to the Parliamentary Assistant to the Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities Discussion Paper on Adult Education Review. https://www.chs.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/chs-adult-education-discussion.pdf

University of Alberta (n.d.). Removing barriers to engagement and learning for deaf students: Multimodal teaching strategies. Centre for Teaching and Learning, University of Alberta. https://www.ualberta.ca/en/centre-for-teaching-and-learning/resources/access-community-belonging/access-and-accessibility/removing-barriers.html

Wahyuni, S., Pantiwati, Y., Sunaryo, H., In’am, A., & Bastian, A. (2025). Strategizing Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Implementation: Enhancing Inclusive Education for Students with Disabilities in Higher Education. Al-Islah Jurnal Pendidikan, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.35445/alishlah.v17i1.6630

Weber, J., Hayward, D., Skyer, M., & Snively, S. (2025). Applied deaf aesthetics toward transforming deaf higher education. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 30(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/jdsade/enae050

Yabe, M. (2015). Benefit factors: American students, International students, and deaf/hard-of-hearing students’ willingness to pay for captioned online courses. Universal Access in the Information Society, 15(4), pp. 773–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-015-0424-1