Improving Accessibility for English Language Learners in Higher Education

Melanie Nickel

Introduction

![]() The growing number of international students in Canada raises important questions about language accessibility in higher education. According to the Government of Canada Stats (2025), 997,820 international learners were studying in Canada at the end of 2024. “By the mid-twentieth century, English had become the global language of science and scholarship. The top 50 scientific journals are published in English, as are the vast majority of internationally circulated scholarly articles” (Atlbach, 2019). When exploring the accessibility of open education resources (OERs), the study by Rets et al. (2023) demonstrated that the majority of English OER texts at different educational levels and subject categories are only suitable for native speakers or English learners with advanced language proficiency. This highlights a critical gap in accessibility, as many ELL students may be excluded from fully engaging with academic content simply because it is not designed with their language needs in mind.

The growing number of international students in Canada raises important questions about language accessibility in higher education. According to the Government of Canada Stats (2025), 997,820 international learners were studying in Canada at the end of 2024. “By the mid-twentieth century, English had become the global language of science and scholarship. The top 50 scientific journals are published in English, as are the vast majority of internationally circulated scholarly articles” (Atlbach, 2019). When exploring the accessibility of open education resources (OERs), the study by Rets et al. (2023) demonstrated that the majority of English OER texts at different educational levels and subject categories are only suitable for native speakers or English learners with advanced language proficiency. This highlights a critical gap in accessibility, as many ELL students may be excluded from fully engaging with academic content simply because it is not designed with their language needs in mind.

I see this reflected in my work, where over half of the college students enrolled in our program are international students. Many of my students are English Language Learners (ELLs). These students include those international learners, newcomers to Canada, and multilingual domestic students for whom English is an additional language. Many of my learners struggle with understanding lectures, course readings, or assignments that are not available in their language. When we talk about accessibility in education, we often think of physical barriers—but language is just as important. If course materials and teaching strategies do not account for linguistic diversity, then we’re not truly offering equal access. I have seen how traditional instruction, along with digital tools that are not inclusive, can create unnecessary obstacles for ELLs.

In this chapter, I explore how I can make higher education more accessible for English Language Learners. I focus on utilizing inclusive instructional design and technology to create more effective learning experiences. I draw on frameworks like Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and culturally responsive teaching to offer practical strategies—like scaffolding, using visuals, and giving students options in how they show their learning. I also highlight digital tools, such as Microsoft Immersive Reader (Microsoft, 2016) and Grammarly (Grammarly, 2009), that can support language development and comprehension. By combining thoughtful design with accessible digital resources, I can create more equitable, inclusive spaces where ELL students are not just accommodated—but supported to succeed. The aim is to contribute toward more equitable, linguistically inclusive teaching environments in an accessible environment for students.

Barriers to Access: Challenges Faced by ELLs in Higher Education

![]() The Canadian Bureau for International Education (2024) reported that international students accounted for over 17% of all post-secondary enrollments in Canada in 2023, and Stats Canada (2024) indicated that the number of international students accounted for 21.2% of all college and university enrollments in 2022/2023. Howe et al. (2023, p. 117) noted that the “key barriers for international students were related to their English language ability, cultural differences, discrimination, homesickness, and differences in academic culture”. Students at my college must pass an English proficiency test before starting their classes. As an instructor, I would see all the students successfully in our program as competent in English, but instructors can overlook the cognitive load involved in academic language acquisition. The English language supports my students receive are to assist them in entering the program, but it is also not integrated into mainstream coursework. This lack of accessibility to students can result in them having difficulty understanding lectures, course readings, and assessments.

The Canadian Bureau for International Education (2024) reported that international students accounted for over 17% of all post-secondary enrollments in Canada in 2023, and Stats Canada (2024) indicated that the number of international students accounted for 21.2% of all college and university enrollments in 2022/2023. Howe et al. (2023, p. 117) noted that the “key barriers for international students were related to their English language ability, cultural differences, discrimination, homesickness, and differences in academic culture”. Students at my college must pass an English proficiency test before starting their classes. As an instructor, I would see all the students successfully in our program as competent in English, but instructors can overlook the cognitive load involved in academic language acquisition. The English language supports my students receive are to assist them in entering the program, but it is also not integrated into mainstream coursework. This lack of accessibility to students can result in them having difficulty understanding lectures, course readings, and assessments.

Accessibility: Theoretical and Pedagogical Frameworks

Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

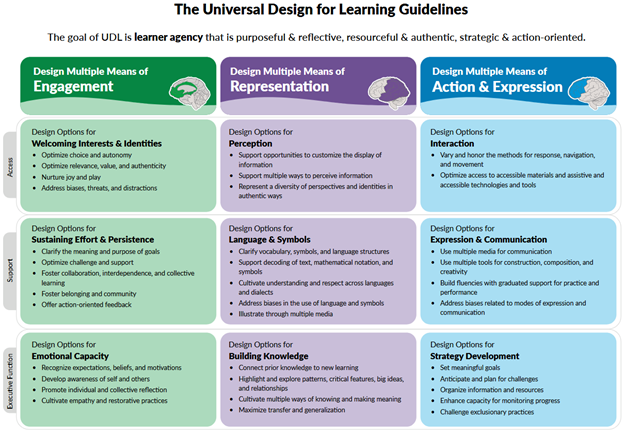

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework developed by CAST (Center for Applied Special Technology) that emphasizes providing multiple means of engagement, representation, and action & expression (CAST, 2018).

For ELL students, UDL could help instructors provide multiple means of engagement by motivating learners through choice and relevance, representation through presenting information in different formats (visual, textual, auditory), and action and expression through varied ways to demonstrate understanding. For ELLs, instructors could use visuals alongside text, offer closed captions on video content, or allow oral presentations as alternatives to essays.

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

![]() Culturally responsive pedagogy recognizes that students bring diverse cultural backgrounds and prior knowledge into the classroom. Instructors who adopt this approach incorporate students’ linguistic and cultural identities into learning, validate non-dominant forms of knowledge, and create inclusive classroom environments. For ELLs, this includes respecting their multilingual backgrounds and building on their strengths.

Culturally responsive pedagogy recognizes that students bring diverse cultural backgrounds and prior knowledge into the classroom. Instructors who adopt this approach incorporate students’ linguistic and cultural identities into learning, validate non-dominant forms of knowledge, and create inclusive classroom environments. For ELLs, this includes respecting their multilingual backgrounds and building on their strengths.

Universities should not continue to impose a single story onto a group of members who are categorized by their race, language, and other identity markers, nor should they force all members to tell the stories in the same language or the same form of a language (Kubota et al., 2023, p. 775).

I can offer technological support to allow learners to respond to questions or complete tasks in their preferred language and then translate. This can help them build confidence and fluency. As a teacher, it is my responsibility to create accessible learning environments.

Instructional Strategies for ELL Accessibility

Effective Instructional Design

Effective instructional design can make a big difference in supporting English Language Learners (ELLs) in higher education. One helpful strategy is scaffolding. Scaffolding means breaking larger tasks into smaller, more manageable steps. Instead of assigning a full essay up front, instructors might start with an outline, then a paragraph draft, and later the final version. Visual tools like graphic organizers, sentence starters, and examples can also help students stay on track. Delivering content in different ways, through video, audio, images, and text, supports students with varied language needs. Many ELLs benefit from being able to hear a lecture while reading a transcript or reviewing an infographic that explains key points. Clear and simple language in instructions also matters. Avoiding idioms, defining academic terms, and offering glossaries or word lists can make a course more accessible without lowering academic expectations. In terms of assessment, giving students options, oral presentations, group work, or visual projects, allows students to demonstrate learning in various ways. Finally, consistent feedback written in plain language and opportunities for peer collaboration, such as study groups or peer review, can build confidence and foster inclusion. These approaches do not just support ELLs—they improve the learning experience for everyone.

Effective instructional design can make a big difference in supporting English Language Learners (ELLs) in higher education. One helpful strategy is scaffolding. Scaffolding means breaking larger tasks into smaller, more manageable steps. Instead of assigning a full essay up front, instructors might start with an outline, then a paragraph draft, and later the final version. Visual tools like graphic organizers, sentence starters, and examples can also help students stay on track. Delivering content in different ways, through video, audio, images, and text, supports students with varied language needs. Many ELLs benefit from being able to hear a lecture while reading a transcript or reviewing an infographic that explains key points. Clear and simple language in instructions also matters. Avoiding idioms, defining academic terms, and offering glossaries or word lists can make a course more accessible without lowering academic expectations. In terms of assessment, giving students options, oral presentations, group work, or visual projects, allows students to demonstrate learning in various ways. Finally, consistent feedback written in plain language and opportunities for peer collaboration, such as study groups or peer review, can build confidence and foster inclusion. These approaches do not just support ELLs—they improve the learning experience for everyone.

Challenging Deficit Thinking: Building Knowledge for ELL Support

“Teacher attitudes appear to represent an equally complex consideration for the delivery of services to second language learners. One issue relates to the observation that educators may view second language learners from a deficit perspective” (Rodrigues, 2010, p. 132). Having educators who understand the challenges and approach them with positivity has a big impact. Institutions can support educators by providing training and guidance on working with ELL students.

“Teacher attitudes appear to represent an equally complex consideration for the delivery of services to second language learners. One issue relates to the observation that educators may view second language learners from a deficit perspective” (Rodrigues, 2010, p. 132). Having educators who understand the challenges and approach them with positivity has a big impact. Institutions can support educators by providing training and guidance on working with ELL students.

Brock et al. (2007) highlight the difficulty in identifying and addressing inappropriate teacher beliefs and stress the need for teacher education programs to take a proactive role in this area. To make these strategies work, both educators and institutions need to be involved. Teachers can take part in training on inclusive teaching, think about their own beliefs around language skills, and work with course designers to build more accessible classes. Colleges and universities should create policies that support multilingual students, offer language help within academic programs, and invest in helpful technology with training for students. Real change only happens when accessibility is built into the system—not treated as an extra. Otherwise, ELL students will continue to face barriers.

Technology for Language Access and Inclusion

Technology can have a positive impact in helping English Language Learners feel more supported in their learning. Tools like Google Translate (Google Translate, n.d.) offer quick help with unfamiliar words, while Microsoft Immersive Reader (Microsoft, 2016) goes a step further by reading text aloud, highlighting grammar, and translating into different languages. Instructors can also choose websites and resources that have those supports built in. For example, the CAST website uses the assistive technology ReadSpeaker (ReadSpeaker, n.d.) and has a button on each page to implement it. ReadSpeaker WebReader (ReadSpeaker, n.d.) is a text-to-speech tool that reads the content of web pages allowed. Within learning platforms, features like captions and transcripts for videos, discussion boards, and embedded glossaries can give students more ways to understand and process information. According to TubeBuddy (2023), YouTube’s auto-translate feature helps make content more accessible by supporting many different languages for both subtitles and dubbing. Subtitles can be automatically translated into the viewer’s preferred language, based on their settings. For dubbing, creators can upload audio tracks in various languages—such as English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, and Italian—allowing viewers to listen in the language that works best for them. These small changes in how content is delivered can help ELLs feel less overwhelmed and more confident in their learning.

Technology can have a positive impact in helping English Language Learners feel more supported in their learning. Tools like Google Translate (Google Translate, n.d.) offer quick help with unfamiliar words, while Microsoft Immersive Reader (Microsoft, 2016) goes a step further by reading text aloud, highlighting grammar, and translating into different languages. Instructors can also choose websites and resources that have those supports built in. For example, the CAST website uses the assistive technology ReadSpeaker (ReadSpeaker, n.d.) and has a button on each page to implement it. ReadSpeaker WebReader (ReadSpeaker, n.d.) is a text-to-speech tool that reads the content of web pages allowed. Within learning platforms, features like captions and transcripts for videos, discussion boards, and embedded glossaries can give students more ways to understand and process information. According to TubeBuddy (2023), YouTube’s auto-translate feature helps make content more accessible by supporting many different languages for both subtitles and dubbing. Subtitles can be automatically translated into the viewer’s preferred language, based on their settings. For dubbing, creators can upload audio tracks in various languages—such as English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, and Italian—allowing viewers to listen in the language that works best for them. These small changes in how content is delivered can help ELLs feel less overwhelmed and more confident in their learning.

Writing and communication tools are also helpful. Grammarly (Grammarly, 2009) and QuillBot (QuillBot, n.d.), for example, support students with grammar, clarity, and tone. It is important to let students know they should reference the use of these tools to prevent it their paper from appearing to be written by AI. Visual tools like Canva (Canva, n.d.) or Piktochart (Piktochart, n.d.) allow students to express their ideas through images and infographics. Platforms like Kahoot! (Kahoot, n.d.) and Quizlet (Quizlet, n.d.) bring vocabulary and review activities to students using gamification. It is important that these tools are easy to access and use. Course content should be compatible with screen readers, available across devices, and supported with clear instructions from instructors. These tools and platforms are not helpful if learners do not know about them or how to use them effectively.

Conclusion

English Language Learners bring diversity to higher education, sharing unique perspectives and knowledge. Those students may face barriers because of language challenges. Approaches such as Universal Design for Learning and culturally responsive teaching can help instructors think about how they design courses to better include and support multilingual students. Simple changes like breaking assignments into steps, using videos and visuals, speaking clearly, and offering different ways to show understanding can make a big difference. Digital tools like captions, translation features, and AI writing helpers give ELL students practical support. Making higher education accessible for ELLs means changing both how we teach and how institutions support those changes. When we put accessibility at the center of our teaching and technology, we take important steps toward creating a more welcoming and fair academic community.

References

Altbach, P. G. (2019, November 19). The dilemma of English-medium instruction in international higher education. World Education News & Reviews. https://wenr.wes.org/2019/11/the-dilemma-of-english-medium-instruction-in-international-higher-education

Brock, C., Moore, D., & Parks, L. (2007). Exploring pre-service teachers’ literacy practices with children from diverse backgrounds: Implications for teacher educators. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23, 898-915.

Canadian Bureau for International Education. (2024). Facts and figures [Data summary]. https://cbie.ca/facts-and-figures/

CAST. (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 3.0. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Grammarly. (2009). Grammarly [Computer software]. https://www.grammarly.com

Google. (n.d.). Google Translate [Computer software]. https://translate.google.com

Howe, E. R., Ramirez, G., & Walton, P. (2023). Experiences of international students at a Canadian university: Barriers and supports. Journal of Comparative & International Higher Education, 15(2), 115–133. https://doi.org/10.32674/jcihe.v15i2.4819

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. (2025). Statistics – Open data. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/reports-statistics/statistics-open-data.html

Kahoot!. (n.d.). Kahoot! [Game-based learning platform]. https://kahoot.com

Kubota, R., Corella, M., Lim, K., & Sah, P. K. (2021). “Your English is so good”: Linguistic experiences of racialized students and instructors of a Canadian university. Ethnicities, 23(5), 758–778. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687968211055808

Lynnfield, M. (2024). Universal Design for Learning guidelines version 3.0 [Graphic organizer]. CAST.

Microsoft. (2016). Immersive Reader [Computer software]. https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/education/products/immersive-reader

Piktochart. (n.d.). Piktochart [Visual communication software]. https://piktochart.com

QuillBot. (n.d.). QuillBot [Writing and paraphrasing tool]. https://quillbot.com

Quizlet. (n.d.). Quizlet [Study and learning tool]. https://quizlet.com

ReadSpeaker. (n.d.). ReadSpeaker [Text-to-speech software]. https://www.readspeaker.com

Rets, I., Coughlan, T., Stickler, U., & Astruc, L. (2023). Accessibility of open educational resources: How well are they suited for English learners? Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 38(1), 38–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2020.1769585

Rodriguez, D., Manner, J., & Darcy, S. (2010). Evolution of Teacher Perceptions Regarding Effective Instruction for English Language Learners. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 9(2), 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192709359423

Statistics Canada. (2024, November 20). Canadian postsecondary enrolments and graduates, 2022/2023 [Data release]. Government of Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/241120/dq241120b-eng.htm

TubeBuddy. (2023, December 13). How the YouTube translation feature makes your videos more accessible. https://www.tubebuddy.com/blog/youtube-translation-auto-dubbing/#:~:text=How%20the%20YouTube%20Translation%20Feature,French%2C%20and%20Italian%2C%20among%20others

YouTube. (n.d.). YouTube [Video-sharing platform]. https://www.youtube.com