Integration of Instructional Design Strategies and Digital Teaching Resources for Dyslexia in Canadian K-12 Education

Isaac Daniel

Introduction

Dyslexia is a learning disability that affects students’ ability to read, write, and process language efficiently. Current advances in dyslexia research have revealed that it is a genetically induced neurological condition impacting several aspects of human cognition, including reading fluency, spelling, and comprehension (Roitz & Watson, 2019). The International Dyslexia Association states that “13-14% of the students have a language-based learning disability” (International Dyslexia Association, n.d.). In the Canadian K-12 system, accessibility barriers are known to hinder students with all kinds of learning disabilities from achieving academic success. Thus, many Canadian K-12 schools struggle to provide adequate support for dyslexic students (Dyslexia Canada, n.d.). Being a neurological condition indicates that dyslexia is personal in its causes and expressions, thus requiring individualized interventions. This paper examines the accessibility challenges associated with dyslexia and presents potential evidence-based solutions to enhance learning outcomes at individualized levels. By integrating instructional design strategies, specifically Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and structured literacy approaches with assistive technologies, educators can create inclusive learning environments that provide individualized solutions for dyslexic learners.

Dyslexia is a learning disability that affects students’ ability to read, write, and process language efficiently. Current advances in dyslexia research have revealed that it is a genetically induced neurological condition impacting several aspects of human cognition, including reading fluency, spelling, and comprehension (Roitz & Watson, 2019). The International Dyslexia Association states that “13-14% of the students have a language-based learning disability” (International Dyslexia Association, n.d.). In the Canadian K-12 system, accessibility barriers are known to hinder students with all kinds of learning disabilities from achieving academic success. Thus, many Canadian K-12 schools struggle to provide adequate support for dyslexic students (Dyslexia Canada, n.d.). Being a neurological condition indicates that dyslexia is personal in its causes and expressions, thus requiring individualized interventions. This paper examines the accessibility challenges associated with dyslexia and presents potential evidence-based solutions to enhance learning outcomes at individualized levels. By integrating instructional design strategies, specifically Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and structured literacy approaches with assistive technologies, educators can create inclusive learning environments that provide individualized solutions for dyslexic learners.

Accessibility Challenges for Dyslexic Students in Canadian K-12 Systems

Dyslexic students in Canada’s K-12 system face a range of accessibility challenges that can significantly impact their educational experience. Generally, the barriers to dyslexia in the Canadian K-12 system have been widely studied. The barriers were grouped into five common kinds, namely: Physical or Architectural Barriers, Informational or Communicational Barriers, Technological Barriers, Organizational Barriers, Attitudinal Barriers (Kovac, 2024). But in this chapter, I will discuss the broad categories of policy, school, and social/personal barriers to accessibility for dyslexia.

Policy Barriers

Policy has been broadly identified as a major issue for accessibility for dyslexic learners. Canadian provinces mostly recognize the issues of reading disability and the need for accessibility and have used the instrument of legislation to address it (Table 1). The main issue, however, is the differences in scope and enforcement. Accessibility has a very broad scope in the provinces, most provinces aiming to improve accessibility in public services, including education. Not all provinces have specific legislation for education and specifically for literary disabilities. Some provinces, like Ontario and Manitoba, have developed and enacted specific standards for education, while others are still in the process of doing so (Table 1).

Policy has been broadly identified as a major issue for accessibility for dyslexic learners. Canadian provinces mostly recognize the issues of reading disability and the need for accessibility and have used the instrument of legislation to address it (Table 1). The main issue, however, is the differences in scope and enforcement. Accessibility has a very broad scope in the provinces, most provinces aiming to improve accessibility in public services, including education. Not all provinces have specific legislation for education and specifically for literary disabilities. Some provinces, like Ontario and Manitoba, have developed and enacted specific standards for education, while others are still in the process of doing so (Table 1).

Developing legislation for dyslexia as a form of learning disability needs to be harmonised for all Canadians in every province. Though there is a general drive to develop legislation and policy to address accessibility barriers for learning disabilities, including dyslexia, the levels of focus on dyslexia vary among provinces. Likewise, the federal policy for accessibility provides a framework for provincial harmonization of accessibility legislation for Canadian provinces, addresses accessibility for all aspects of government involvement, which education is just a component (Accessible Canada Act, 2019) (Table 1). Since dyslexia attacks the literacy foundation of society, policy scope and enforcement need to cover this problem to effectively help dyslexic students. While some provinces like Ontario have begun to acknowledge the importance of specific dyslexia intervention like structured literacy, implementation remains inconsistent. This creates a patchwork of support, where access depends heavily on geography and school board priorities (Dyslexia Canada, n.d.). Specific focus on harmonizing accessibility for dyslexia as opposed to scattered policies for learning disabilities intervention, is needed to address barriers to dyslexia accessibility and boost literacy in the Canadian educational system.

Table 1.

Canadian Provinces that Have Enacted Legislation on Accessibility for Learning Disabilities Including Dyslexia. (Accessible Canada Act, 2019)

| Province | Legislation | Year Enacted | Reference |

| Ontario | Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) | 2005 | AODA – BDO Canada |

| Manitoba | The Accessibility for Manitobans Act | 2013 | Manitoba AMA – BDO Canada |

| Nova Scotia | Accessibility Act | 2017 | Nova Scotia Act – BDO Canada |

| British Columbia | Accessible British Columbia Act | 2021 | BC Act – BDO Canada |

| Saskatchewan | Accessible Saskatchewan Act | 2023 | Saskatchewan Act – BDO Canada |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | An Act Respecting Accessibility in the Province | 2021 | NL Act – BDO Canada |

| New Brunswick | Accessibility Act (standards pending) | 2024 | NB Act – BDO Canada |

| Quebec | Act to Secure Handicapped Persons in the Exercise of Their Rights | 1978 (amended 2004) | Quebec Act – BDO Canada |

Accessibility Barriers at the School Level

In school situation perspectives, accessibility barriers for dyslexic learners in Canada often present in combinations. The Ontario Human Right Commission (2017) identified limited early screening, inadequate teacher training, limited access to structured literacy, stigma and emotional impact, and inconsistent accommodations as accessibility barriers that are most prevalent in Ontario’s K-12 system.

In school situation perspectives, accessibility barriers for dyslexic learners in Canada often present in combinations. The Ontario Human Right Commission (2017) identified limited early screening, inadequate teacher training, limited access to structured literacy, stigma and emotional impact, and inconsistent accommodations as accessibility barriers that are most prevalent in Ontario’s K-12 system.

Limited early screening capacity delays diagnosis of dyslexia, but it is a direct result of many teachers lacking the skill in the diagnosis. Inadequate Teacher Training has a direct effect on early screening (Ciuffetelli and Conversano, 2021). This is a way of highlighting teacher training as a direct cause of limited capacity for early screening. This delay in diagnosis can lead to academic struggles and emotional distress, which is when most teachers recognise issues. Many general and resource teachers are also ill-equipped with the tools or training to support dyslexic learners as a result of the organizational direction of schools’ boards (Ciuffetelli and Conversano, 2021).

Limited access to modern teaching tools and technologies is another school-based accessibility barrier for dyslexic learners. Effective reading instruction for dyslexic students often requires a structured literacy approach—explicit, systematic teaching of phonics, spelling, and comprehension, and the use of technologies, which will be discussed in detail later. However, many educators in Canada are not trained in the science of reading methods (Ameline et al., 2022). There is also limited access to technologies for individualized cases. The result is limited teacher capacity to identify and support dyslexic students effectively.

Social/Personal Accessibility Barriers to Dyslexia

![]() There is also the personal and social aspect of barriers to accessibility for dyslexia. Labelling theory is pertinent in dyslexic students as labels have a complex relationship with individuals’ experiences of dyslexic people (Wissell et al., 2025). Labels like “disability” or “learning disorder” can carry negative connotations, affecting how dyslexic individuals are perceived and how they perceive themselves. Wissell et al. (2025) concluded that many adults with dyslexia reject the term “disability,” associating it with shame or inadequacy. Instead, they prefer identity-affirming terms like “dyslexic” or “learning difference,” which better reflect their lived experiences and strengths. Labels constitute a barrier to accessibility to students who face low self-esteem for not meeting literacy standards in standardized school tests.

There is also the personal and social aspect of barriers to accessibility for dyslexia. Labelling theory is pertinent in dyslexic students as labels have a complex relationship with individuals’ experiences of dyslexic people (Wissell et al., 2025). Labels like “disability” or “learning disorder” can carry negative connotations, affecting how dyslexic individuals are perceived and how they perceive themselves. Wissell et al. (2025) concluded that many adults with dyslexia reject the term “disability,” associating it with shame or inadequacy. Instead, they prefer identity-affirming terms like “dyslexic” or “learning difference,” which better reflect their lived experiences and strengths. Labels constitute a barrier to accessibility to students who face low self-esteem for not meeting literacy standards in standardized school tests.

Peer issues also contribute to social and personal barriers to dyslexia accessibility. Reading difficulties subtly reinforce exclusion rather than fostering inclusion when learners begin to have that sense of not meeting up with peers. Riddick (2001) argues that traditional literacy standards can transform reading difficulties into disabilities. In that sense, peer issues also become an accessibility barrier that may lead to dyslexic learners avoiding accessibility interventions to avoid being tagged (Leseyane et al., 2018). In other words, peer issues snowball into personal barriers and accessibility barriers, underscoring the necessity of personalized accessibility interventions for individual dyslexic students.

Addressing these three broad groups of accessibility barrier require wholistic approaches to support dyslexic students. The next part of the paper will focus on integrated approaches encompassing instructional strategies and assistive technologies to enhance accessibility for dyslexia in schools.

Instructional Strategies for Dyslexia

Instructional strategies provide a way to deal with barriers to accessibility for dyslexia at the policy, school, and social/personal levels. Instructional strategies targeted at dyslexia are designed to enhance reading skills and foster comprehension. Notable methods of instructional strategies include: Universal Design for Learning (UDL), Structured Literacy Approaches, and Assistive Technologies.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

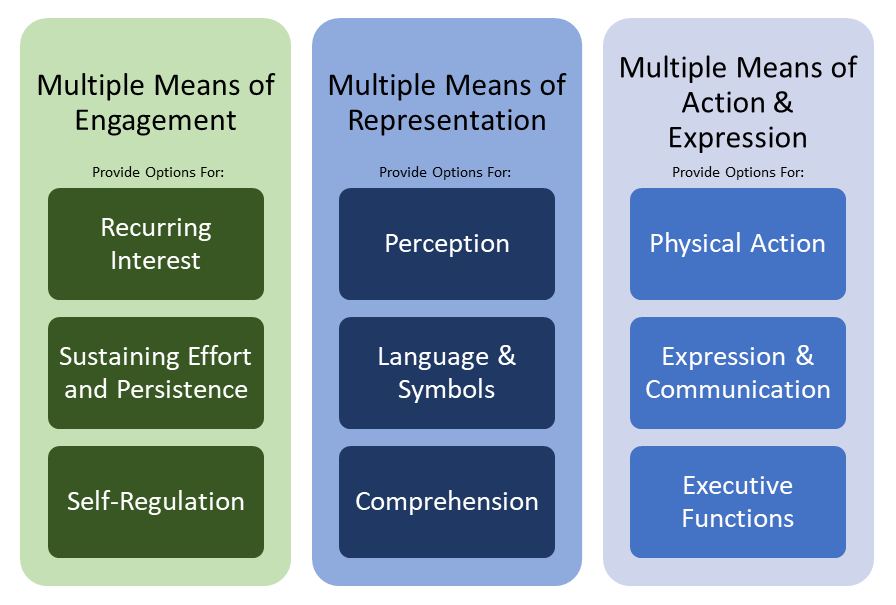

The Universal Design for Learning (UDL) was developed by David Rose of Harvard and the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) (Meyer et al., 2014). The idea was inspired by universal design movements in architecture and product design that called for design to be usable by all people to the greatest extent possible. Researchers at CAST used the work of Vygotsky and Bloom in adapting this principle into the three-part UDL framework. The features of UDL that are relevant to dyslexia are highlighted in Table 2.

The tenets of UDL are multiple means of representation, which emphasize varied presentation of information (visuals, audio, interactive media) to accommodate diverse learning styles. UDL also involves using multiple means of action and expression to present class content, which encourages varied learners to express their knowledge (writing, speaking, multimedia projects). Multiple means of engagement focus on sparking motivation through personalized interests and culturally responsive content.

Structured Literacy

Structured literacy is an instructional strategy specifically developed for dyslexia. It is a label developed by the International Dyslexia Association (IDA, 2019) to better prepare teachers for literacy instruction. Structure literacy is an instructional model that focuses on building and developing the foundational literacy skills of phonemic awareness, letter-sound correspondences, syllables, morphology, syntax, and semantics using explicit, systematic judgments (Table 2). Structured literacy has therefore become the base for dyslexia accessibility intervention.

Structured literacy is an instructional strategy specifically developed for dyslexia. It is a label developed by the International Dyslexia Association (IDA, 2019) to better prepare teachers for literacy instruction. Structure literacy is an instructional model that focuses on building and developing the foundational literacy skills of phonemic awareness, letter-sound correspondences, syllables, morphology, syntax, and semantics using explicit, systematic judgments (Table 2). Structured literacy has therefore become the base for dyslexia accessibility intervention.

Structured literacy is, by implication, term science of reading. It goes beyond the cue method of reading that helps learners to use clues like pictures to read words instead of analyzing texts and how it sounds. It involves word-level decoding ability (i.e., word recognition) and listening (language) comprehension ability (Gough and Tunmer, 1986). The use of structured literacy helps educators to engage the spectrum of dyslexia in learners with decoding or comprehension, depending onthe learner’s individual accessibility needs. Thus, enabling personalized accessibility interventions.

Assistive Technologies and Digital Teaching and Learning Resources

While structured literacy is typically paper-based accessibility, digital resources involved in dyslexia use digital resources accessibility. The use of assistive technologies is usually digital resources that have proffered solutions to dyslexia. Digital resources can be divided into computer software and, more recently, artificial intelligence, including robotics (Fung et al., 2025). Smith and Hartingh (2020) highlighted the most common software assistive technology tools for enhancing accessibility for dyslexia, they are: text-to-speech and speech-to-text apps, NaturalReader (NaturalSoft, n.d.), and Google Read & Write (Texthelp, 2023). There are other digital tools like dyslexia-friendly fonts and formatting tools like Open Dyslexic (n.d.) font and BeeLine Reader (2017) for improved readability. Moreover, interactive learning platforms have been developed as adaptive learning tools such as MindMeister (MeisterLabs, 2025) and BookShare (Beneficient Technology, 2024) to support dyslexic students. And finally, there are audiobooks and digital library resources like Learning Ally (2025), which provide accessible reading materials.

While structured literacy is typically paper-based accessibility, digital resources involved in dyslexia use digital resources accessibility. The use of assistive technologies is usually digital resources that have proffered solutions to dyslexia. Digital resources can be divided into computer software and, more recently, artificial intelligence, including robotics (Fung et al., 2025). Smith and Hartingh (2020) highlighted the most common software assistive technology tools for enhancing accessibility for dyslexia, they are: text-to-speech and speech-to-text apps, NaturalReader (NaturalSoft, n.d.), and Google Read & Write (Texthelp, 2023). There are other digital tools like dyslexia-friendly fonts and formatting tools like Open Dyslexic (n.d.) font and BeeLine Reader (2017) for improved readability. Moreover, interactive learning platforms have been developed as adaptive learning tools such as MindMeister (MeisterLabs, 2025) and BookShare (Beneficient Technology, 2024) to support dyslexic students. And finally, there are audiobooks and digital library resources like Learning Ally (2025), which provide accessible reading materials.

Paudel et al. (2024) reviewed both traditional assistive software (like text-to-speech and speech-to-text tools) and innovative interventions incorporating mobile apps, augmented reality, and other digital solutions. The review concluded on the evolving role of highly computerized interventions like augmented reality in inclusive education above the traditional assistive technologies. The most recent dyslexia accessibility experiment with artificial intelligence and robotics tools (Fung et al., 2025).

Table 2.

Summary of Possible Instructional Strategies for Dyslexia Accessibility

| Strategy | Key Features | Notes on Implementation in Canadian Classrooms | Academic Sources | |

| Universal Design for Learning (UDL) | An instructional framework that calls for flexible teaching methods, multiple means of representation, action/expression, and engagement to minimize learning barriers for all students. | Some Canadian schools are beginning to incorporate UDL principles—often alongside other strategies—to foster inclusive classrooms. UDL encourages educators to design lessons that naturally accommodate diverse learner needs, including those with dyslexia, by offering varied pathways to understanding and demonstration. | Meyer et al., (2014)

CAST (2018) Al-Azawei, et al. (2016) Javed et al., 2024 |

|

| Structured Literacy | Explicit, systematic, and cumulative instruction in phonological awareness, sound–symbol association, syllable structure, morphology, syntax, and semantics. | Many Canadian districts are moving toward structured literacy; however, implementation can vary widely between school boards. Professional development remains critical. | International Dyslexia Association (2019)

Ameline et al. (2022) |

|

| Assistive Technology | Incorporates tools such as text-to-speech software, audiobooks, and speech-to-text applications to help students access content and express themselves effectively. Advances include use of artificial intelligence and robotics to proffer individualized interventions. | Digital supports are increasingly integrated in classrooms, though disparities exist between well-funded urban settings and more remote or under-resourced areas in Canada. | Stuart & Yates (2018)

Smith and Hartingh (2020) Paudel and Acharya (2024) Fung et al. (2025) |

Integration of Instructional Strategies for the Dyslexia Spectrum

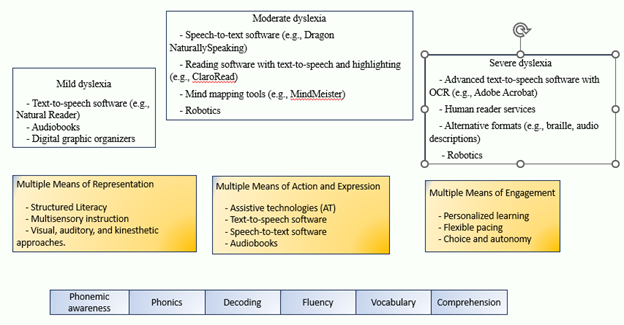

Dyslexic learners express different levels of reading and writing impairment; thus, an enhanced accessibility must take cognisance of the type and level of dyslexia of individual students. The IDA (n.d.) categorized dyslexia into mild, moderate, and severe, with a wide range of spectrum between categories that an individual can be. With the current advances in accessibility instructional strategy tools, educators have a wide range of choices of strategies to engage in order to provide effective accessibility for the wide range of dyslexia spectrum at individual levels. Thus, in this paper, a graphic chart of the intersection of the three instructional strategies is presented to enable educators’ choices of accessibility tools for different dyslexia severity (Figure 1).

Conclusion

This chapter has offered a review of barriers to accessibility for dyslexic students in the Canadian K-12 educational system and presents an intersection to enhance accessibility. The place of policy, school settings, and social/ personal barriers are highlighted as a background to underscore the potential of integrated instructional strategies and digital technology as enhancers of accessibility for personalized interventions for dyslexic students.

An intersection chart was presented as an integrated approach to enhancing accessibility for dyslexic learners. The chart is to present a visual template that educators can use to map relationships between instructional strategies at the levels of structured literacy, UDL, and assistive technologies. Educators can draw a line to connect assistive technologies to structured literacy needs associated with the severity of the dyslexic condition through UDL approaches relevant to the judgment of the educator.

The chart is not particularly software; it is more of a visual aid that gives flexibility to the educator to make choices. The chart can further be developed into a data-driven decision-making tool when it is activated by data and algorithms. Hopefully, it will provide a precision accessibility tool for personalized interventions for dyslexic learners by joining structured literacy materials with assistive digital technologies through UDL instructional approaches.

References

Accessibility Act Canada (2019). Accessibility legislation, standards, and regulations in Canada. https://www.bdo.ca/insights/accessibility-legislation-standards-and-regulations-in-canada

Al-Azawei, A., Serenelli, F., & Lundqvist, K. (2016). Universal Design for Learning: A Content Analysis of Peer-Reviewed Journal Papers from 2012 to 2015. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. 16 (3), pp. 39-56. doi: 10.14434/josotl.v16i3.19295

Ameline, J., Chyung, J., and Thompson, E. (2022). Structured Literacy and the Science of Reading. Canadian School Libraries Journal. https://journal.canadianschoollibraries.ca/structured-literacy-and-the-science-of-reading/

AODA (n.d.). Disability Barriers. https://www.aoda.ca/disability-barriers/

BeeLine Reader (2017). https://www.beelinereader.com/

Beneficent Technology (2024). Bookshare: Learn Without Limits. https://www.bookshare.org/

CAST (2018). UDL guidelines. [Web page]. https://udlguidelines.cast.org/more/research-evidence/

Ciuffetelli, P. D. and Conversano, P. (2021). Narratives of systemic barriers and accessibility: poverty, equity, diversity, inclusion, and the call for a post-pandemic new normal. Front. Educ. 6(1), 704663. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.704663.

Dyslexia Canada (n.d.). https://dyslexiacanada.org

Fung, K.Y., Fung, K.C., Lui, T.L.R., Sin, K. F., Lee, L. H., Qu, H. and Song, S. (2025). Exploring the impact of robot interaction on learning engagement: a comparative study of two multi-modal robots. Smart Learning Environment 12(12), https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-024-00362-1

Gough, P. B. and Tunmer. W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education. 7: 6 – 10.

International Dyslexia Association (IDA) (n.d.). Dyslexia Basics. https://dyslexiaida.org/dyslexia-basics/

International Dyslexia Association. (2019). Structured Literacy: An introductory guide. [Web page]. https://dyslexiaida.org/teachers/

Javed, S., Muniandy, M., Lee, C.K. (2024). Enhancing teaching and learning for pupils with dyslexia: A comprehensive review of technological and non-technological interventions. Educ Inf Technol (29), 9607–9643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-12195-5

Kovac, L. (2024, September 10). Disability barriers for students with dyslexia. [Web page]. Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act. https://aoda.ca/disability-barriers-for-students-with-dyslexia/

Learning Ally (2025). Empowering struggling readers including students with dyslexia. https://learningally.org/

Leseyane, M., Mandende, P., Makgato, M., & Cekiso, M. (2018). Dyslexic learners’ experiences with their peers and teachers in special and mainstream primary schools in North-West Province. African Journal of Disability, 7(0), 363. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v7i0.363

MeisterLabs (2025). MindMeister: Collaborative Mind Mapping. https://www.mindmeister.com/

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice. CAST Professional Publishing.

Naturalsoft Ltd (n.d.). NaturalReader. https://www.naturalreaders.com/

Ontario Human Rights Commission (2017). Right to Read. http://www.ohrc.on.ca

OpenDyslexic (n.d.). A Typeface for Dyslexia. https://opendyslexic.org/

Paudel, S., and Acharya, S. (2024). A comprehensive review of assistive technologies for children with dyslexia. arXiv:2412.13241 [cs.HC]. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.13241

Riddick, B. (2001). Dyslexia and inclusion: Time for a social model of disability perspective? International Studies in Sociology of Education, 11(3), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620210100200078

Roitsch, J., and Watson, S. (2019). An Overview of Dyslexia: Definition, Characteristics, Assessment, Identification, and Intervention. Science Journal of Education, 7(4), 81 -86. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.sjedu.20190704.11

Stuart, A., and Yates, A. (2018). Inclusive classroom strategies for raising the achievement of students with dyslexia. New Zealand Journal of Teachers’ Work. 15 (2), 100-104.

Smith, C., Hattingh, M.J. (2020). Assistive Technologies for Students with Dyslexia: A Systematic Literature Review. In: Huang, TC., Wu, TT., Barroso, J., Sandnes, F.E., Martins, P., Huang, YM. (eds) Innovative Technologies and Learning. ICITL 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (), vol 12555. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63885-6_55

Wissell, S., Hudson, J., Flower, R. L., & Goh, W. (2025). ‘I hate calling it a disability’: Exploring how labels impact adults with dyslexia through an intersectional lens. Neurodiversity, 3. https://doi.org/10.1177/27546330241308540 (Original work published 2025).