30

Bonnie Stewart

The idea of publics is central to scholarship. Scholarly pursuits are financed in part through public purses, and scholarship — in its idealized form, at least — contributes back to publics. Research. Knowledge. The public good. These are the returns through which scholarship justifies its place in society.

Yet scholarship has never been particularly open to the public. It operates, in increasingly-rationalized incarnations, as a carefully-managed ecosystem of gatekeeping measures: the prestige hierarchies of academic credentials and the academic publishing system comprise a powerful inside-baseball discourse. Contemporary scholars have tended to be far more accountable to the system itself than to actual publics, except in rare cases where the scope or consequence of the work — as in the cases of McLuhan or Milgram — has been rendered public by media.

Until now.

Over the past decade and more, digital networked communications have crept into scholarship. List-servs, then blogs, then social networking platforms crept into corners of scholarly practice. Twitter in particular has become a means by which many scholars create and curate public identities and share their work and that of others. But open networked scholarship is, by definition, open to those who choose to participate; the price of admission is not a degree or an accolade or a particular number of publications in the right journals. The price of admission is the willingness to engage, in public, over time, in sustained and iterative discussions over ideas and knowledge and what counts as the public good, among other things.

And that price is getting a little higher — and a little more public — all the time.

This week, I defend a dissertation on networked scholarship; an ethnography, based in extensive participant observation, document analysis, and interviews. It’s odd, this point of supposed closure. When I look back on the nearly two years in which I’ve been embedded in envisioning, conducting, and writing this research, my days look little different at the end than they did in the middle, or at the start. I am still on Twitter, watching and contributing and trying to make sense of things, much as I was on Twitter throughout the thesis process and for years before I ever even imagined this dissertation. I am still reading and learning and sharing in broader networks, though my neglected blog — spurned for months as I tried to discipline myself to the craft of publishable academic papers — might beg to differ. My study has ended, and my Research Ethics Board approval has expired. But there has been no particular sense of closure or leave-taking in the process. I have not left my ethnographic field.

Yet if there is minimal change in me, the field itself — the water in which I swim as a networked identity and a networked scholar — has altered. I have had the privilege and discomfort of researching and analyzing my small subset of participants through a period of relatively dramatic shift in Twitter as a participatory culture.

Sure, since networks are distributed rather than monolithic or centrally-controlled, the social norms and memes that constitute in-group behavior within academic Twitter (and Twitter more broadly) shift constantly. But occasionally, these shifts alter the way the platform operates as a public.

The increasingly public consequences of academic Twitter may be, in the end, among the most important things I observed during my research… even if they weren’t what I thought I was studying all along.

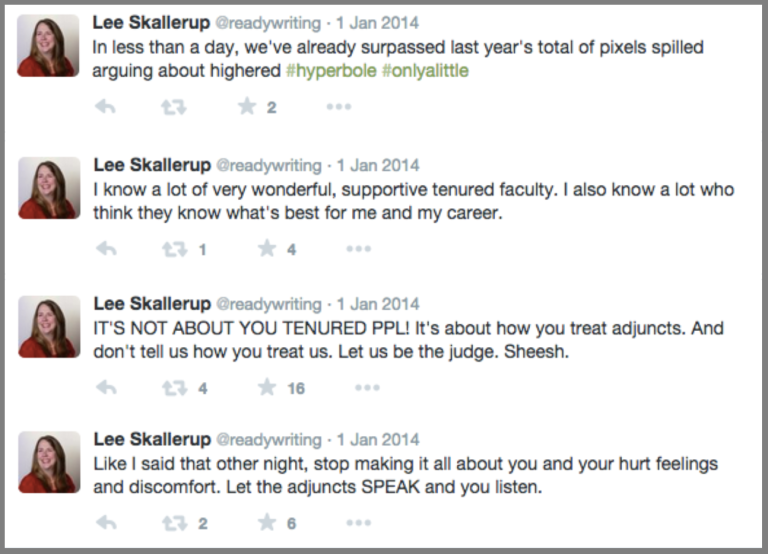

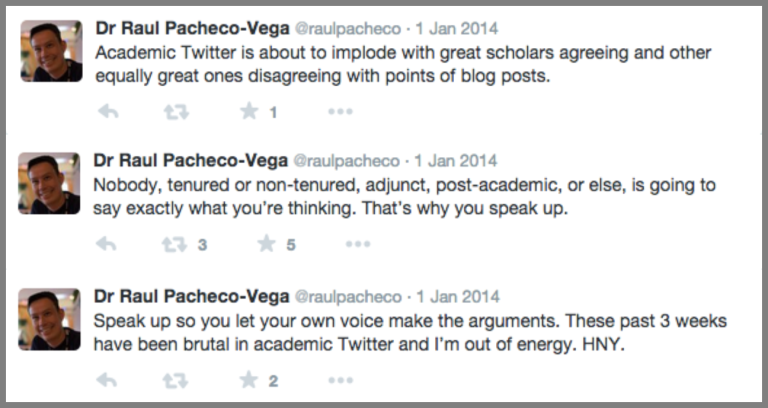

It was New Years Day, 2014, when I first realized academic Twitter was changing in front of me. I was smack in the middle of three months of daily ethnographic observation, looking at the Twitter practices of 14 highly-networked scholars from various disciplines and various parts of the globe. Since academia runs on the Christian calendar and the majority of academics are neither teaching nor grading post-Christmas, I’d expected the final week of the old year to be busy-ish but banal. I hadn’t expected my research timeline to erupt in fraught and widespread back-and-forth exchanges around adjuncts and advocacy and how tenured academics should — and should not — speak to the untenured. And I hadn’t expected that the eruption would signal a permanent shift in what it meant to be a public scholar. Looking back through my research data from that day, though, I think it did.

Commentary, response, analysis, re-tweets and further contributions spread out from initial volleys to constitute more than half the discussion in my research feed during the week leading up to New Years 2014. And I screencapped more than 50 tweets related to the debate — from a research sample of only 14 — on New Years Day alone.

I am not here for a recap of the old wounds of that week’s controversy. It scabbed over, inevitably; the key parties worked out the rancor in their own ways. The larger issues of inequity, precarity, and respect remain… unsolved. What lingers, though, is not the content of the fracas so much as its markers. A year down the road and a few dozen rodeos later, these markers are familiar as what I now think of as Call-Out Culture in action:

- the vitriol was public and sustained

- it was generated not by pre-existing factionalism but by specific public statements and responses made online

- it aligned a group perceived to have power and privilege against a group without

Specific scholars were called out by name, on record, for the implications of their words and positions, and in turn called out others; because the dispute had its origins in a public conflict between two individuals, it was difficult to engage without effectively “piling on” to a heated and highly-personalized debate. Yet the conversation was so pervasive, amplified through re-tweet and commentary, that to be present within the network almost demanded a public staking out of position, at risk of otherwise appearing oblivious or insensitive to the issue at hand.

I was a newly-fledged Twitter Researcher. I made notes.

“Speaks to an alteration of academic Twitter’s implicit social contract?” — ethnographic research note, January 1, 2014

“If one does not participate or signal, can one still belong?” — ethnographic research note, January 1, 2014

“The people on the power side don’t seem to realize they’re on the power side.” — ethnographic research note, January 1, 2014

To be an engaged and aware participant in academic Twitter at that juncture was to be embroiled — whether willingly or not — within a contested realm of speech, and one with public, ethical implications. The debate expanded and trended to the extent that silence and the refusal to engage publicly began to take on the appearance of an intentional signal, rather than the absence of a signal. Thus the calling out extended beyond those engaged in the conversation to those whose lack of engagement was seen as tacit support for the status quo.

In short, it ran like this: some people were called out in public for their speech. Some people were called out in public for their lack of speech. Some people reacted to being called out by defending their good intentions rather than owning their effects on others.

New Years 2014, in short, was a harbinger of the year to come.

Looking back over the year and more since, I now recognize that the way in which the adjunct controversy played out had its roots in changing norms around public speech and speakability. Twitter, as a platform, had already begun to shift — academic Twitter was simply catching up. Mikki Kendall’s August 2013 hashtag #SolidarityIsForWhiteWomen and Suey Park’s December 2013 #NotYourAsianSidekick, among others, had called out implicit racism, exclusion, and inequities in representation, had raised consciousness of the implications of public speech on Twitter, and had opened up the platform as a site of concentrated political action around issues of identity and speech.

Relatedly, the now-infamous firing of Justine Sacco in December 2013, framed by Jon Ronson in the New York Times as “How One Stupid Tweet Blew Up Justine Sacco’s Life,” had demonstrated the capacity of mass Twitter outrage to generate swift real-world effects.

These newly-tactical uses of Twitter were fresh and reverberating in January 2014, and their capacity to catapult small-scale tweets to extremely large publics was just beginning to have effects on the participatory culture of Twitter more broadly. I’d been watching, all of it. But I hadn’t expected it all to land on my quiet academic Twitter doorstep with quite such an immediate thud.

As Ronson’s recent NYT headline shows, the effects of tactical Twitter have been taken up predominantly in terms of victimization. One stupid tweet can ruin your life, goes the dominant narrative, and open you to pillory and career carnage. This frame, however, fails to interrogate the operations of racism, sexism, and other forms of privilege in determining what kinds of “stupid tweets” lend themselves to viral outrage, and ignores the ways in which Call-Out Culture operates to speak for those whose identity markers are regularly silenced or smeared in “stupid tweets.” As Tressie MacMillan Cottom notes, framing Sacco as a mere hapless victim of the collapse between (intended) private speech and mass publics contributes to reinforcing the sorts of casual, privileged dehumanization of others that many tactical uses of Twitter push back against:

I get why people would not like that. Being stripped of your personhood to stand in the gap for a group of people against your will is rage inducing…You are ceaselessly primed for every implication that you have become another tick mark when you were busy living and laughing and being a wholly fallible human being. It is horrible to lose a job for that. It is a privilege to have never before lost a job for that. (“Racists Getting Fired: The Sins of Whiteness on Social Media”)

I seldom stand in the gap, online. My experience of academic Twitter prior to New Year’s 2014 had been one primarily marked by the intersections of my whiteness and my gender performance and my in-network centrality and my relative obscurity everywhere else. I am not the target of “stupid tweets.” And thus, when I think about changes in academic Twitter and its tactical uses and effects over the past year, then, the question I focus on is “changes for whom?”

Tressie points that for many people, standing in the gap is nothing new. Yes, Twitter’s increasing tendency towards calling people out lends alarming scale and reach to that experience of identity reduction, and this collapse of public and private is not something to be taken lightly. But when it is framed, as in Ronson’s NYT piece, primarily as a spectre haunting unmarked bodies, threatening supposedly-innocuous white people like Justine Sacco with standing in the gap for reasons that amount to little more than schadenfreude, something is missing from the analysis. Twitter as a tactical public allows for abuses, and for defenses of power and privilege. It also allows for bodies marked by race, gender, class, queerness, disability, and intersections of these and other identity facets to publicly resist being made to stand in the gap. It forces a reckoning with the ways that casual, even ephemeral public speech can reinforce the marginalization of others. It has become a space less tolerant of speech unwilling to account for its own power relations and assumptions.

This matters for scholarship, and for the ideals of knowledge and the public good that scholarship espouses.

What has changed in the year and more since January 2014, I think, is that networks’ capacity to turn into full-scale publics at any moment has become increasingly visible. Where academic Twitter once seemed quietly parochial and collegial almost to the point of excess, it is now thrust into the messy, contested business of being truly open to the public.

What has also changed is that the conversation on adjuncts shifted a bit, in academic Twitter. Consciousness was raised. Initiatives emerged. It is a little less acceptable, now, to speak from positions that deny the experiences and voices of contingent academic employees. Does this solve the problem? It does not and it cannot. But it changes the shape of the public scholarly sphere, and makes it just a little more open to those who stand in the gap for higher ed. And this is something.