29

Amanda Licastro

I started writing this article on the day the Trump administration announced they were bombing Syria. A dark coincidence. The announcement came via my New York Times alerts just as I finished responding to Bonnie Stewart in regards to an article I sent her about the prejudice Canadians harbor against Muslim refugees — an article she immediately added to her keynote that evening. Bonnie and I were in correspondence because she recently Skyped into my Introduction to Digital Publishing class at Stevenson University to speak about her involvement in a Kickstarter campaign to fund refugee families on Prince Edward Island where she lives and teaches. Bonnie’s experience resonated because my students were working with Asylee Women’s Enterprise (AWE), a local nonprofit that offers resources to asylum seekers in Baltimore, Maryland. The students were building web content for AWE as our final project. My class was paired with AWE in the spring of 2016 — before Trump, before the travel ban, before the bombings — when the Director of Service Learning, Christine Moran, reached out to me to create a collaborative experiential learning opportunity for my course.

As Christine proved when recruiting me for this project, service learning is a “high impact practice” building the communication, technical, and professionalization skills employers look for in new graduates. Students would be applying the concepts of digital publishing to a real world, client-based objective. As demonstrated in the reflection letter of student Ryan Roche, “having a client to work with helps give the class a direction and helps to really show the ‘behind-the-scenes’ action that takes place in the digital publishing field.” Additionally, my 200-level Intro to Digital Publishing class partnered with a 300-level Interactive Advanced Design course in order to produce a professional product for the client. This collaboration created an interdisciplinary, team-based learning environment that involved design thinking and project-oriented learning objectives — digital pedagogy at its finest. However, this plan also involved attempting a collaboration across physical space and political divides, a complex feat that had the potential to fail on multiple fronts. In my experience, innovation involves “failing forward,” but in this case failure involved disappointing a client that was counting on the results of our experiment. Needing to produce a viable website for AWE reframed the way I think about risk in the classroom.

Digital Citizens

As a professor of digital rhetoric I frame my pedagogy as a path to cultivating “digital citizens,” or students who actively, critically, and thoughtfully participate in online spaces. Stemming from Kathleen Yancey’s call to action in “Writing in the 21st Century,” the intention is to “help our students compose often, compose well, and through these composings, become the citizen writers of our country, of our world, and the writers of our future” (1). This is why, at all levels, I ask students to compose in public spaces (for more on this see Mark Sample’s “What’s Wrong With Writing Essays”). Students write blog posts about course content, live-tweet their readings of novels, create multimodal projects, and perhaps most importantly, respond to each other’s work in these digital spaces. Options for privacy controls and anonymity are always provided, but even writing within the “public” audience of their peers helps develop audience awareness and rhetorical strategy. Low stakes assignments of this nature prepared students for the work of writing content for AWE’s website, but still the considerable stakes of composing for a client intimidated my students, and quite frankly, me.

The anxiety surrounding writing publicly was exacerbated by the fact that students were writing about and for asylum seekers in the United States in a particularly tumultuous political climate. Some students expressed feelings of inadequacy when confronted with this task, while others found the high stakes incentivizing. As student Taylor Barksdale writes in her final reflection letter:

Having a real client gave us confirmation that the work that we would be doing was indeed meaningful. I know it gave me an increased amount of motivation to turn in the best work I possibly could because the work we turned in would actually be going live on a website for the world to see. More importantly, I knew the work we were doing was for a website with the incredibly urgent goal of getting people to help asylum seekers in America.

On the other hand, one student commented “[i]n redesigning Asylee Women’s Enterprise’s website, the burden placed on students was heavy, especially for an introductory course” (anonymous evaluation). That, of course, is true. Perhaps 200-level students should not be responsible for a professional website, even when paired with an advanced course? Or perhaps I needed to provide greater oversight and stronger critique throughout the process? I know in the future I would schedule the introduction to publishing course at the same time as the advanced interactive design course so that the students could meet during class time and collaborate formally under the guidance of both professors. But these expressions of inadequacy also stem from the difficulty in balancing the technical skills of the course and the content needed to teach students about digital publishing and the politics of asylum.

Because I teach students from a wide range of political backgrounds, I avoid revealing my political leanings in the classroom. Certainly, topics covered in my courses are inherently political — we talk about gender, race, sexuality, ability, and the freedom of information — but these are offered as launching points for discussion and debate. The invitation to work with AWE demanded I engage in the political directly. It felt imperative to ensure students had the space to grapple with this complex issue, while still producing content that offered support for the asylum seekers. Therefore, for the first time in my teaching history, I shared my personal immigration story with the class. As someone who rarely reveals personal information to my students, I took this risk in order to open a safe and confidential space for my students to share their stories. Although I acknowledge that, as Sam Hamilton argues, “taking risks as a instructor pales in comparison to taking risks as just about anything else (most notably taking risks as a student),” I felt the need to offer them a piece of myself — to demonstrate my personal connection to this issue — in return for their willingness to work toward a shared outcome.

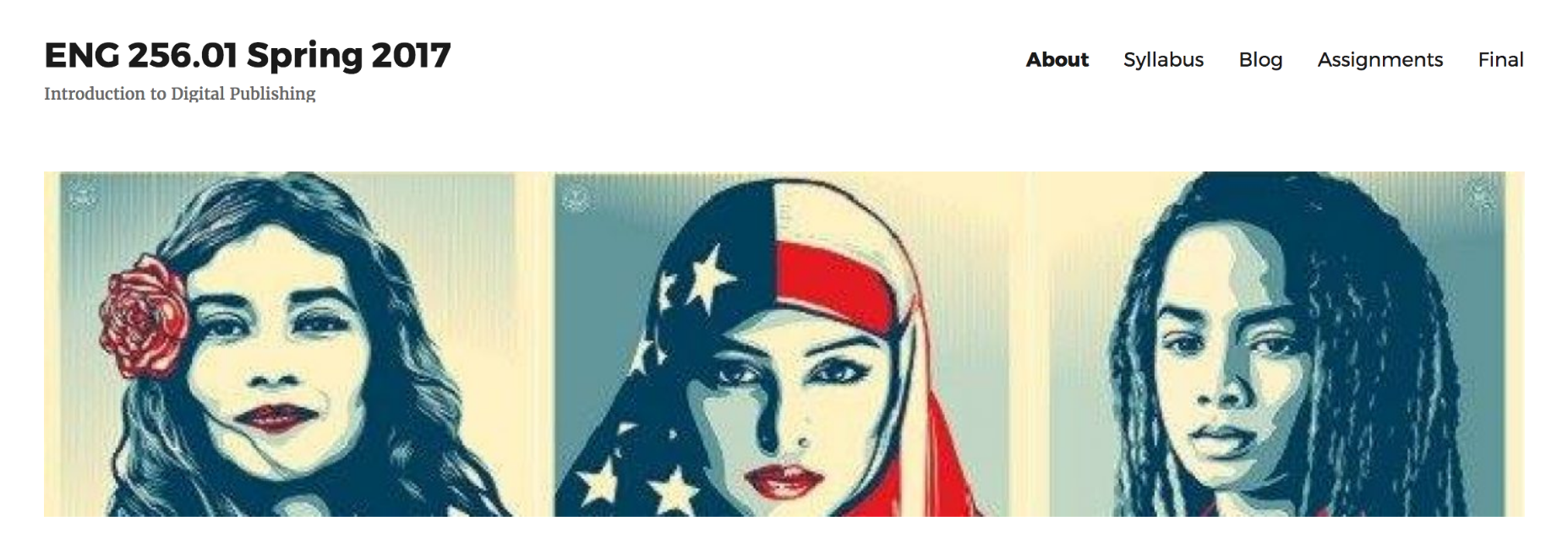

Participating in this service learning course led me to reflect on the political rhetoric — both acknowledged and inferred — of my class materials. In this case, the success of the course was contingent on the students actively participating in public, digital citizenship. The students needed to be aware that the goal of this course was to aide asylum seekers in the United States. To emphasize this point, I used visual rhetoric in the header for our course site:

The imagery not only unveiled my politics, it also welcomed students to engage in a specific form of citizenship. Much like Amy J. Wan proposes in “In the Name of Citizenship,” this course gave me an opportunity to question “what kinds of citizens” I was hoping to cultivate (29). I was asking students to share their stories; to connect to people and a cause that may be outside of their own experience. I was requesting not only empathy, but vulnerability. In highlighting the political nature of this course, I realized that empathy and vulnerability are often unspoken requirements we summon from our students — not only in service learning courses, but also in the undefined demands of our writing assignments. As Maha Bali writes in “Critical Digital Citizenship: Promoting Empathy and Social Justice Online,” the aim is to “help young people become more empathetic critical digital citizens.” This course forced me to make my intentions transparent, and to offer anyone who was not interested in participating the opportunity to drop the course. Bali’s question from “On Whose Terms Are We (Digital) Citizens?,” namely, “Do we recognize that sometimes, in our zeal to help students question, we may also be hampering their capacity to truly listen to the ‘other’ with an open mind?” replays in my mind. I did not want to discourage conservative students from taking this course when their views would be welcomed and valued. Despite having a right-leaning student body at Stevenson University, no one who registered for this course dropped.

High Stakes Learning

What started as a fairly typical service learning initiative quickly became a matter of life or death. Once Trump announced the travel ban, AWE extended their services to men and children, opening their doors to an influx of families fleeing from over 15 countries around the world. AWE provides legal counsel, housing, transportation services, hot meals, English courses, wellness activities, clothing and food donations, and above all a community center for their clients. The website the students created for AWE needed to present all of these important resources in a way that addressed an audience of asylum seekers, volunteers, and donors. Students faced the challenge of crafting content that was narrative and informative, well-researched yet approachable, and all with language simple enough to be translated by a web-based tool. Additionally, I was mindful that everything we created would be maintained by the overworked AWE staff. In order to accomplish these goals, I wanted to teach students rhetorical analysis, information architecture, editing, multimodal composition, social media writing, and somehow provide enough context to break down the stereotypes associated with refugees and asylum seekers.

It was important for the students to understand that AWE addresses the needs of asylum seekers, not refugees. Both my students and I learned about the significance of this distinction through our interactions with AWE and through the research students did to develop the content for the site. Yes, we have a refugee crisis. However, when refugees arrive to the US they are provided with resources to sustain their basic needs for up to six months. Certainly that is not enough, but because they are pre-vetted and approved they are welcomed into our country with somewhere to live and a caseworker to facilitate the process. Asylum seekers often flee from their homes with no warning, and therefore have no plan if and when they cross the border. Take, for example, the woman who was a business owner in good standing in her community who gave birth to a child with a disability and was accused of witchcraft and denied medical services for her at-risk newborn. Or the lawyer who provided counsel to citizens in support of the opposing political party whose 13-year-old daughter was kidnapped as revenge. These are professionals forced to leave their homes and businesses to come to the US with practically nothing and only a slim hope of proving they qualify for asylum through a grueling process that typically drags on for years.

During my visit to AWE, the lunchroom was filled with quiet young mothers and their less quiet babies. The women picked at plates of donated noodles, occasionally leaving to participate in a yoga class or use one of two computers to look for work. An infant slouched in a high chair that was too big, a puppy nipped at toddler pulling its tail, and a baby was passed from an elderly male volunteer to Tiffany who fed the baby a goldfish cracker as she continued to tell me about their need for “trendier” clothing donations. The place embodied the adage that it takes a village to raise a child. I felt ill-equipped to help. In an attempt to turn my feeling of inadequacy into action, I harnessed the spirit of that room and rallied my community of my female friends — many of whom have young children — to gather clothing and collected donations from colleagues at Stevenson. Similarly, as my students began visiting the center, they were inspired to give their time outside of our final project. For example, RISE, our women’s group on campus, organized a drive to collect feminine hygiene products to donate. These are small steps, but the first in what I hope to be an ongoing mission to sustain this partnership.

The partnership between my class and AWE proved to be a learning experience for all of us. In “Developing Accounts of Instructor Learning: Recognizing the Impacts of Service-Learning Pedagogies on Writing Teachers,” the authors argue that students and instructors engaged in service learning programs experience increased community engagement, reflective practices, and and critical engagement (Leon et al.). By visiting AWE and working together to create a website for the organization, my students and I have a shared experience that will resonate far beyond the general course concepts. Student Ryan Diepold articulated this in his reflection letter:

Reading about asylum seekers and refugees only goes so far. Taking research and regurgitating it out into a research paper only goes so far. If I did not go down to Asylee Women’s Enterprise and talk with the volunteers and asylee [sic] seekers first hand, I am positive that I would not have put forth the energy and time into this project that I did.

Perhaps this is the ideal outcome for a community partnership. My students developed an awareness that the content covered in class had real world applications. However, I learned that not every teaching experiment is entirely successful, and that I need to improve the structure and balance of my course content.

Sustainability

In this course students needed to acquire basic WordPress skills and gain knowledge of universal design, while learning to write for a translingual audience and provide reliable information. Final projects included a multimodal transportation map of Baltimore, video interviews with AWE volunteers, “day-in-the-life” narratives of AWE clients, and an interactive map of information about refugees from specific countries. Students learned to install plugins, communicate directly with a client, and vet highly politicized “facts.” None of this could have been accomplished with a traditional learning management system, or without guest speakers with expertise in a variety of content areas. I wanted students to see this work as a contribution to a community project that would live on after the semester ended.

I admit to contributing to a vast digital graveyard of student artifacts in my prior teaching in the digital humanities. Since entering my first full-time faculty position, I have been working toward ending this cycle by creating long-term projects that students build upon each year. Not only does this create consistency across semesters, it also gives students a greater sense of audience and purpose. As student Brie Green puts it,

Knowing there was a cause and people counting on us, and knowing that we were creating real content that was going out into the world made the process much more meaningful than textbook work that would only be retained for the time required — ultimately ending up in a recycle bin at the end of the semester.

The goal here is to offer this service learning course every spring so that the AWE website is updated every year by a new group of students. However, annual updates are not enough. Therefore, I also worked with the chair of my department to set up an internship for an English major to help design curriculum for the English classes at AWE, and ideally update the website regularly. This internship will offer English majors interested in teaching a chance to gain valuable experience without an education degree, and put their digital publishing skills into practice. It is also a recognized contribution to my career-oriented university, and thus makes sense as a faculty career strategy as well.

Looking to the Future

Nothing ever goes as planned. My best intentions for this course were deterred by emergencies, staffing shifts, and scheduling conflicts. Many students struggled to communicate with their partners, or failed to execute grandiose technical architecture, but all of them managed to produce thoughtful — and above all useful — content for the AWE website. Although from my perspective as the instructor, the final projects represented a wide range of ability levels and effort, the director of AWE was elated with the work presented by my students. Several of the projects went above and beyond my expectations and provided AWE with resources they can surely use for years to come.

As preparation for a new year begins, I am struggling to do my own reflective revisions to this course. In her work on global digital citizenship, Maha Bali states that “in higher education, one can promote social justice and empathy that develops critical citizenship in three ways: apolitical civic engagement through community service (which research has shown promotes adult political civic engagement), simulation of authentic political contexts in a safe environment, and intercultural learning experiences” (Critical Digital Citizenship: Promoting Empathy and Social Justice Online). In the future, I would like to work on the intercultural experience of this course. How can I create the space for authentic intersectional learning? I want to incorporate more of the voices of the population we are severing into my syllabus. First, I am going to assign Americanah by the Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. But while this novel is relevant and raw, it is still fictionalized. What I hope to do is present the uncensored narratives of asylum seekers and refugees in a way that does not usurp or fetishize the stories, but rather engages the student in honest reflection and revelation.