28

A specialized database—often called a research, library, or subscription database—allows targeted searching on one or more specific subject areas (e.g., engineering, medicine, Latin American history, etc.), for a specific format (i.e., books, articles, conference proceedings, streaming video, images, etc.), or for a specific date range during which the information was published. Most of what specialized databases contain can not be found by open web search engines like Google or Bing.

There are several types of specialized databases. The following are a sampling of ones available through the GCC Library:

- Bibliographic – citation and/or abstract (summary) about published works

- Reference sources – subject-specific encyclopedia or dictionary sources like those found in Credo

- Full-text – details plus the complete text of the items

- Multimedia – various types of media such as Kanopy for streaming videos, ArtStor for images, or Mango Languages for language learning

- Mixed – a combination of other types, such as multimedia and full-text

Important Note about Databases vs. Open Websites

If you recall from earlier lessons about the deep web, databases are not available from the open free web. They remain behind a paywall, whether commercial or through libraries. Open websites are freely available and there is no restriction to access them. The quality is less reliable and it takes more time, skills, experience, and critical thinking to evaluate sources from the open web. The good and the bad are all thrown together, unrestricted.

There is often much confusion when it comes to databases vs open websites. Databases are expensive commodities (recall the frame/theme, Information has Value) that libraries pay handsomely so that users, such as students, scholars, and the general public may access these resources by virtue of their association with the library or the institution that supports that library. Because of the economics involved in the creation, production, dissemination, restriction, and potential usefulness of this information, this information holds particular value monetarily and otherwise.

Most databases still contain information that has been made available by a publisher in order to meet the need of the audience or users who consume this information. Publishers are the middlemen who make the product available to the consumer (recall that the Open Access movement attempts to cut out these middlemen due to unreasonable fees and charges assessed to subscribers, like libraries and individual users, who are captive to these costs). The entire ecosystem of how information as a commodity and as a means of exchange is considered part of the knowledge of the information economy, which as consumers we all participate in. This is why such information is not freely available.

Because the information in databases has been selected and reviewed by editors, and in the case of scholarly journals, by peer-reviewers who vet the pre-published sources according to the highest and most rigorous standards, such information, once published is considered much more reliable, credible, and authoritative.

While you, as an information consumer are able to access this information because you have a special status as a member of a particular library or institution, may access these databases through the internet, it is easy to confuse databases with open websites that are freely available. In reality, the internet provides access to both open websites and to databases. It’s the route by which you can get access to content, free or restricted. However, this doesn’t make them the same though, and recognizing these distinctions will help you to think critically about your sources.

Because librarians and libraries are involved in selecting databases based on criteria that reflect the user community, consider the library or librarians as gatekeepers to better, more quality information, in large part. The ability and the facility you gain (by taking classes like LIB 100!) in developing your power searching and critical thinking skills are what will set you above and apart from the rest and thus more competitive in the world of information.

When to Use Specialized Databases

Search specialized databases to uncover information that is not available through a regular web search. Specialized databases are especially helpful if you require a specific format or up-to-date, scholarly information on a specific topic.

Many databases are available both in a free version and in a subscription version. Your affiliation with a subscribing library grants you access to member-based services at no cost to you.

Tip: Free vs. Subscription?

In some cases, the data available in free and subscription versions are the same, but the subscription version provides some sort of added value or enhancement for searching or viewing items.

Database Scope

Information about the specific subject range, format, or date range a particular specialized database covers is called its scope. A specialized database may be narrow or broad in scope, depending on whether it, for instance, contains materials on one or many subject areas.

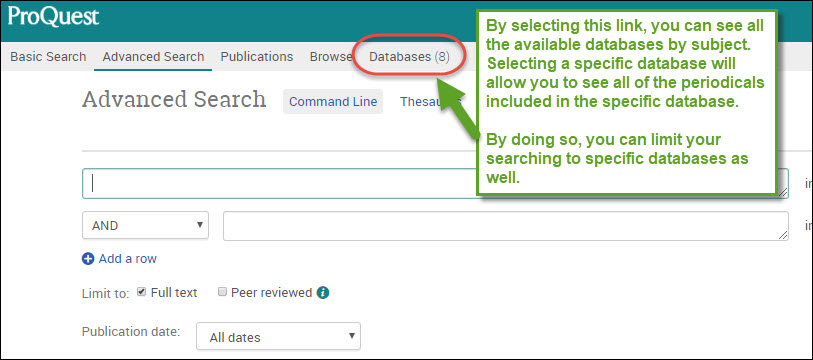

Below is a screenshot of several databases available via ProQuest. If you click on the list of databases, you will see scope information, including the date range and the subject areas covered in each.

Once you are aware of a database’s scope, you’ll be able to decide whether the database is likely to have what you want (for instance, journal articles as opposed to conference proceedings). Reading about the scope can save you time you would have otherwise wasted searching in databases that do not contain what you need.

How to Use Them

Most databases have the same advanced search function available to you. Some functions might vary. For example, the truncation or wild card symbol might be different in one database compared to another. To learn what specific functions are available to you, look for a link labeled Help, Tips, Search Tips, Search Help, etc., in each database.

Example: Academic Search Complete

Academic Search Complete is a general article database available through most academic and large public libraries that is often recommended for undergraduate research projects. As a general or multidisciplinary database, it covers many different subject areas. Academic Search Complete is similar to ProQuest in terms of functionality (how it works and what options you have). Although it contains fewer sources, it may contain more relevant sources than ProQuest depending on the topic. When searching one, consider searching the other to make sure you cover your bases.

Movie: Academic Search Complete – The Basics

Keyword Searching

Although keyword search principles apply (as described in Precision Searching), you may want to use fewer search terms since the optimal number of terms is related to database size. Search engines like Google and Bing work best with more search terms since they index billions of web pages and additional terms help narrow the results. Each scholarly database indexes a fraction of that number, so you are less likely to be overwhelmed by results even with one or two keywords than you would be with a search engine.

Databases are better searched by beginning with only a few general search terms, reviewing your results, and if necessary, limiting them in some logical way. Use quotation marks around phrases to increase the relevance of your results. (See Limiting Your Search below.)

Limiting Your Search

Many databases allow you to choose which areas (called fields) of items to search for your search term(s), based on what you think will turn up documents that are most helpful.

For instance, you may think the items most likely to help you are those whose titles contain your search term(s). In that case, your search would not show you any records for items whose titles do not have your term(s). Or maybe you would want to see only records for items whose abstracts contain the term(s).

When this feature is available, directing your search to particular fields, you are said to be able to “limit” your search. Most search engines, on the open web and in databases, will default to searching anywhere or full text of a record. While this type of search will maximize your search results, your total results may not be the most relevant and to find the most relevant sources you may need to sift through more than you are willing to spend the time doing. Other fields that may be searched besides anywhere or in full text include searching in the citation and abstract or the document title, both of which will yield fewer results that are more relevant.

Subject Heading Searching

One precision searching technique may be helpful in databases that allow it, and that’s subject heading searching. Subject heading searching can be much more precise than keyword searching because you are sure to retrieve only your intended concept.

Subject searching is helpful in situations such as:

- There are multiple terms for the same topic you’re interested in (example: cats and felines).

- There are multiple meanings for the same word (example: cookie the food and cookie the computer term).

- There are terms used by professionals and terms used by the general public, including slang or shortened terms (example: flu and influenza).

Here’s how it works:

Database creators work with a defined list of subject headings, which is sometimes called a controlled vocabulary. That means the creators have defined which subject terms are acceptable and assigned only those words to the items it contains. The resulting list of terms is often referred to as a thesaurus. When done thoroughly, a thesaurus will not only list acceptable subject headings, but will also indicate related terms, broader terms, and narrower terms for a concept.

Tip: Finding Useful Subject Headings

Try this strategy to find useful subject headings. Remember it by thinking of the letters KISS:

- Keyword-search your topic.

- Identify a relevant item from the results.

- Select subject terms relevant to your topic from that item’s subject heading.

- Search using these subject terms. (Some resources will allow you to simply click on those subject terms to perform a search. Others may require you to copy/paste a subject term[s] into a search box and choose a subject field.)

Records and Fields

A database is made up of records that represent sources. By selecting an item from your results list, you are selecting the record for that source. Each record contains multiple fields containing various identifiable parts of the source such as the title of the article, the author(s), the summary/abstract, the volume/issue, page numbers, subject headings associated with the source. and of course, the fulltext of the body of the source.

Each record describes an item that can be retrieved and gives you enough information so that, hopefully, you can decide whether it should meet your information need. The descriptions are in categories that provide different types of information about the item. These categories are called “fields.” Some fields may be empty of information for some items, and the fields that are available depend on the type of database.

Example: Database Fields

A bibliographic database describes items such as articles, books, conference papers, etc. Common fields found in bibliographic database records are:

- Author.

- Title (of book, article, etc.).

- Source title (journal title, conference name, etc.).

- Date.

- Volume/issue.

- Pages.

- Abstract.

- Descriptive or subject terms.

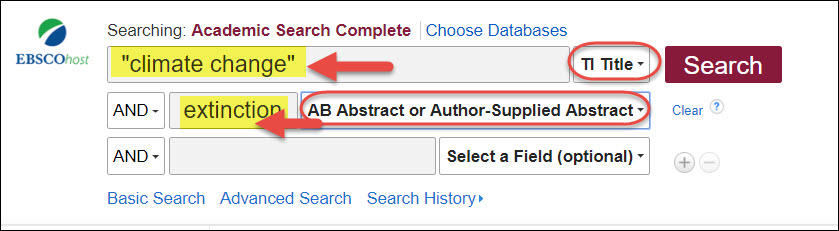

Note the search in the first image below. Both concepts are being searched anywhere or fulltext. Click on the image to see the number of results this search retrieves.

By separating your concepts, you may designate different fields for each concept. Click on the image below to see the number of results this search strategy/statement retrieves.

In contrast, a product database record might contain the following fields:

- Product Name.

- Product Code number.

- Color.

- Price.

- Amount in Stock.