18 Free Exercise in the Past Decade

Conflicts Between the Free Exercise and Establishment Clauses

The First Amendment contains two separate clauses referencing religion. The first, which we have examined at length, protect the beliefs and sometimes actions of religious individuals from government regulation. The second clause aims to prevent religious control of the government, both to prevent religion from being corrupted by political power and to protect adherents of other faiths (or nonreligious individuals) from the dictates of a government run by a particular religious denomination.

The consensus view of the Establishment Clause is that it prohibits the establishment of official churches at the federal and later state levels. Beyond that, just as with the Free Exercise Clause, there is considerable debate over what degree of “separation” from religion governments must maintain. This debate is beyond the scope of these materials.

That said, while the two religion clauses often work in concert, they can also come into conflict with one another. Take, for example, a state program that gives vouchers to students who attend private schools. If the state extends these credits to students who attend religious schools, it could be accused of violating the Establishment Clause because tax revenue is supporting religious institutions. If, however, the state excludes religious students from the voucher program, it could also be accused of violating the neutrality that the Free Exercise Clause requires.

Justices in our earlier Free Exercise cases sometimes raised these concerns, noting that how one construes the Free Exercise clause can affect the interpretation of the Establishment Clause. To simplify somewhat, stronger protections for free exercise rights can weaken establishment restrictions on the government, and vice versa.

In line with the broader theme of this chapter–the Roberts Court’s increasing protection of religious rights, particularly when culture war issues are involved–it shouldn’t be surprising that the Court has weakened Establishment Clause limits on state governments in order to maintain a robust Free Exercise doctrine. The most recent and important of these rulings took place in 2022 when the Court heard a lawsuit from a public school’s football coach who had been fired for holding prayers on the field after games. The Court held that the school’s firing violated the Free Exercise Clause, and could not be defended by appealing to the Establishment Clause.

Kennedy v. Bremerton School District

597 U.S. ___ (2022)

Facts: Kennedy, a public high school football coach, lost his job after repeatedly offering public prayers at midfield following football games. Kennedy sued, arguing the termination was a violation of his First Amendment rights under the Free Exercise Clause. The school district countered that its firing was justified under the Establishment Clause and that as a government actor, Kennedy’s conduct put them at risk for a lawsuit.

Question: 1) Is a public school employee’s prayer during school sports activities protected speech, and 2) if so, can the public school employer prohibit it to avoid violating the Establishment Clause?

Vote: 1) No, 2) No (6-3 both)

For the Court: Justice Gorsuch

Concurring opinion: Justice Thomas

Concurring opinion: Justice Alito

Dissenting opinion: Justice Sotomayor

JUSTICE GORSUCH delivered the opinion of the Court.

Joseph Kennedy lost his job as a high school football coach because he knelt at midfield after games to offer a quiet prayer of thanks. Mr. Kennedy prayed during a period when school employees were free to speak with a friend, call for a reservation at a restaurant, check email, or attend to other personal matters. He offered his prayers quietly while his students were otherwise occupied. Still, the Bremerton School District disciplined him anyway. It did so because it thought anything less could lead a reasonable observer to conclude (mistakenly) that it endorsed Mr. Kennedy’s religious beliefs. That reasoning was misguided. Both the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment protect expressions like Mr. Kennedy’s. Nor does a proper understanding of the Amendment’s Establishment Clause require the government to single out private religious speech for special disfavor. The Constitution and the best of our traditions counsel mutual respect and tolerance, not censorship and suppression, for religious and nonreligious views alike.

I

A

Joseph Kennedy began working as a football coach at Bremerton High School in 2008 after nearly two decades of service in the Marine Corps. Like many other football players and coaches across the country, Mr. Kennedy made it a practice to give “thanks through prayer on the playing field” at the conclusion of each game. In his prayers, Mr. Kennedy sought to express gratitude for “what the players had accomplished and for the opportunity to be part of their lives through the game of football.” Mr. Kennedy offered his prayers after the players and coaches had shaken hands, by taking a knee at the 50-yard line and praying “quiet[ly]” for “approximately 30 seconds.”

Initially, Mr. Kennedy prayed on his own. But over time, some players asked whether they could pray alongside him. Mr. Kennedy responded by saying, “‘This is a free country. You can do what you want.’” The number of players who joined Mr. Kennedy eventually grew to include most of the team, at least after some games. Sometimes team members invited opposing players to join. Other times Mr. Kennedy still prayed alone. Eventually, Mr. Kennedy began incorporating short motivational speeches with his prayer when others were present. Separately, the team at times engaged in pregame or postgame prayers in the locker room. It seems this practice was a “school tradition” that predated Mr. Kennedy’s tenure. Mr. Kennedy explained that he “never told any student that it was important they participate in any religious activity.” In particular, he “never pressured or encouraged any student to join” his postgame midfield prayers…

For over seven years, no one complained to the Bremerton School District (District) about these practices.

It seems the District’s superintendent first learned of them only in September 2015, after an employee from another school commented positively on the school’s practices to Bremerton’s principal. At that point, the District reacted quickly. On September 17, the superintendent sent Mr. Kennedy a letter. In it, the superintendent identified “two problematic practices” in which Mr. Kennedy had engaged. First, Mr. Kennedy had provided “inspirational talk[s]” that included “overtly religious references” likely constituting “prayer” with the students “at midfield following the completion of . . . game[s].” Second, he had led “students and coaching staff in a prayer” in the locker-room tradition that “predated [his] involvement with the program.”

The District explained that it sought to establish “clear parameters” “going forward.” It instructed Mr. Kennedy to avoid any motivational “talks with students” that “include[d] religious expression, including prayer,” and to avoid “suggest[ing], encourag[ing] (or discourag[ing]), or supervis[ing]” any prayers of students, which students remained free to “engage in.” … In offering these directives, the District appealed to what it called a “direct tension between” the “Establishment Clause” and “a school employee’s [right to] free[ly] exercise” his religion. To resolve that “tension,” the District explained, an employee’s free exercise rights “must yield so far as necessary to avoid school endorsement of religious activities.”

…

On October 14, through counsel, Mr. Kennedy sent a letter to school officials informing them that, because of his “sincerely-held religious beliefs,” he felt “compelled” to offer a “post-game personal prayer” of thanks at midfield. He asked the District to allow him to continue that “private religious expression” alone…

On October 16, shortly before the game that day, the District responded with another letter…It forbade Mr. Kennedy from engaging in “any overt actions” that could “appea[r] to a reasonable observer to endorse . . . prayer . . . while he is on duty as a District-paid coach.” The District did so because it judged that anything less would lead it to violate the Establishment Clause.

B

After receiving this letter, Mr. Kennedy offered a brief prayer following the October 16 game. When he bowed his head at midfield after the game, “most [Bremerton] players were . . . engaged in the traditional singing of the school fight song to the audience.” Though Mr. Kennedy was alone when he began to pray, players from the other team and members of the community joined him before he finished his prayer…

On October 23, shortly before that evening’s game, the District wrote Mr. Kennedy again. It expressed “appreciation” for his “efforts to comply” with the District’s directives, including avoiding “on-the-job prayer with players in the . . . football program, both in the locker room prior to games as well as on the field immediately following games.” The letter also admitted that, during Mr. Kennedy’s recent October 16 postgame prayer, his students were otherwise engaged and not praying with him, and that his prayer was “fleeting.” Still, the District explained that a “reasonable observer” could think government endorsement of religion had occurred when a “District employee, on the field only by virtue of his employment with the District, still on duty” engaged in “overtly religious conduct.” …

After the October 23 game ended, Mr. Kennedy knelt at the 50-yard line, where “no one joined him,” and bowed his head for a “brief, quiet prayer.” The superintendent informed the District’s board that this prayer “moved closer to what we want,” but nevertheless remained “unconstitutional.” After the final relevant football game on October 26, Mr. Kennedy again knelt alone to offer a brief prayer as the players engaged in postgame traditions. While he was praying, other adults gathered around him on the field…

C

Shortly after the October 26 game, the District placed Mr. Kennedy on paid administrative leave and prohibited him from “participat[ing], in any capacity, in . . . football program activities.” In a letter explaining the reasons for this disciplinary action, the superintendent criticized Mr. Kennedy for engaging in “public and demonstrative religious conduct while still on duty as an assistant coach” by offering a prayer following the games on October 16, 23, and 26…

In an October 28 Q&A document provided to the public, the District admitted that it possessed “no evidence that students have been directly coerced to pray with Kennedy.” The Q&A also acknowledged that Mr. Kennedy “ha[d] complied” with the District’s instruction to refrain from his “prior practices of leading players in a pre-game prayer in the locker room or leading players in a post-game prayer immediately following games.” But the Q&A asserted that the District could not allow Mr. Kennedy to “engage in a public religious display.” Otherwise, the District would “violat[e] the . . . Establishment Clause” because “reasonable . . . students and attendees” might perceive the “district [as] endors[ing] . . . religion.”

While Mr. Kennedy received “uniformly positive evaluations” every other year of his coaching career, after the 2015 season ended in November, the District gave him a poor performance evaluation… Mr. Kennedy did not return for the next season.

II

A

After these events, Mr. Kennedy sued in federal court, alleging that the District’s actions violated the First Amendment’s Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses. He also moved for a preliminary injunction requiring the District to reinstate him. The District Court denied that motion, concluding that a “reasonable observer . . . would have seen him as . . . leading an orchestrated session of faith.”

… On appeal, the Ninth Circuit affirmed.

Following the Ninth Circuit’s ruling, Mr. Kennedy sought certiorari in this Court. The Court denied the petition…

B

After the case returned to the District Court, the parties engaged in discovery and eventually brought cross-motions for summary judgment. At the end of that process, the District Court found that the “‘sole reason’” for the District’s decision to suspend Mr. Kennedy was its perceived “risk of constitutional liability” under the Establishment Clause for his “religious conduct” after the October 16, 23, and 26 games.

The court found that reason persuasive too. Rejecting Mr. Kennedy’s free speech claim, the court concluded that because Mr. Kennedy “was hired precisely to occupy” an “influential role for student athletes,” any speech he uttered was offered in his capacity as a government employee and unprotected by the First Amendment… Alternatively, even if Mr. Kennedy’s speech qualified as private speech, the District Court reasoned, the District properly suppressed it. Had it done otherwise, the District would have invited “an Establishment Clause violation.” Turning to Mr. Kennedy’s free exercise claim, the District Court held that, even if the District’s policies restricting his religious exercise were not neutral toward religion or generally applicable, the District had a compelling interest in prohibiting his postgame prayers, because, once more, had it “allow[ed]” them it “would have violated the Establishment Clause.”

C

The Ninth Circuit affirmed…

Later, the Ninth Circuit denied a petition to rehear the case en banc over the dissents of 11 judges…

We granted certiorari.

III

Now before us, Mr. Kennedy renews his argument that the District’s conduct violated both the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment. These Clauses work in tandem. Where the Free Exercise Clause protects religious exercises, whether communicative or not, the Free Speech Clause provides overlapping protection for expressive religious activities. That the First Amendment doubly protects religious speech is no accident. It is a natural outgrowth of the framers’ distrust of government attempts to regulate religion and suppress dissent…

Under this Court’s precedents, a plaintiff bears certain burdens to demonstrate an infringement of his rights under the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses. If the plaintiff carries these burdens, the focus then shifts to the defendant to show that its actions were nonetheless justified and tailored consistent with the demands of our case law.

We begin by examining whether Mr. Kennedy has discharged his burdens, first under the Free Exercise Clause, then under the Free Speech Clause.

A

Under this Court’s precedents, a plaintiff may carry the burden of proving a free exercise violation in various ways, including by showing that a government entity has burdened his sincere religious practice pursuant to a policy that is not “neutral” or “generally applicable.” Should a plaintiff make a showing like that, this Court will find a First Amendment violation unless the government can satisfy “strict scrutiny” by demonstrating its course was justified by a compelling state interest and was narrowly tailored in pursuit of that interest.

That Mr. Kennedy has discharged his burdens is effectively undisputed. No one questions that he seeks to engage in a sincerely motivated religious exercise…

The contested exercise before us does not involve leading prayers with the team or before any other captive audience. Mr. Kennedy’s “religious beliefs do not require [him] to lead any prayer . . . involving students.” At the District’s request, he voluntarily discontinued the school tradition of locker-room prayers and his postgame religious talks to students. The District disciplined him only for his decision to persist in praying quietly without his players after three games in October 2015.

… In this case, the District’s challenged policies were neither neutral nor generally applicable. By its own admission, the District sought to restrict Mr. Kennedy’s actions at least in part because of their religious character… Prohibiting a religious practice was … the District’s unquestioned “object.”

The District’s challenged policies also fail the general applicability test. The District’s performance evaluation after the 2015 football season advised against rehiring Mr. Kennedy on the ground that he “failed to supervise student athletes after games.” But, in fact, this was a bespoke requirement specifically addressed to Mr. Kennedy’s religious exercise. The District permitted other members of the coaching staff to forgo supervising students briefly after the game to do things like visit with friends or take personal phone calls…

B

When it comes to Mr. Kennedy’s free speech claim, our precedents remind us that the First Amendment’s protections extend to “teachers and students,” neither of whom “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

Of course, none of this means the speech rights of public school employees are so boundless that they may deliver any message to anyone anytime they wish. In addition to being private citizens, teachers and coaches are also government employees paid in part to speak on the government’s behalf and convey its intended messages.

To account for the complexity associated with the interplay between free speech rights and government employment, this Court’s decisions in Pickering (1968), Garcetti (2005), and related cases suggest proceeding in two steps. The first step involves a threshold inquiry into the nature of the speech at issue. If a public employee speaks “pursuant to [his or her] official duties,” this Court has said the Free Speech Clause generally will not shield the individual from an employer’s control and discipline because that kind of speech is—for constitutional purposes at least—the government’s own speech.

At the same time and at the other end of the spectrum, when an employee “speaks as a citizen addressing a matter of public concern,” our cases indicate that the First Amendment may be implicated and courts should proceed to a second step. At this second step, our cases suggest that courts should attempt to engage in “a delicate balancing of the competing interests surrounding the speech and its consequences.” Among other things, courts at this second step have sometimes considered whether an employee’s speech interests are outweighed by “‘the interest of the State, as an employer, in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees.’”

Both sides ask us to employ at least certain aspects of this Pickering–Garcetti framework to resolve Mr. Kennedy’s free speech claim… At the first step of the Pickering–Garcetti inquiry, the parties’ disagreement thus turns out to center on one question alone: Did Mr. Kennedy offer his prayers in his capacity as a private citizen, or did they amount to government speech attributable to the District?

… it seems clear to us that Mr. Kennedy has demonstrated that his speech was private speech, not government speech. When Mr. Kennedy uttered the three prayers that resulted in his suspension, he was not engaged in speech “ordinarily within the scope” of his duties as a coach. He did not speak pursuant to government policy. He was not seeking to convey a government-created message. He was not instructing players, discussing strategy, encouraging better on-field performance, or engaged in any other speech the District paid him to produce as a coach…

The timing and circumstances of Mr. Kennedy’s prayers confirm the point. During the postgame period when these prayers occurred, coaches were free to attend briefly to personal matters—everything from checking sports scores on their phones to greeting friends and family in the stands.

We find it unlikely that Mr. Kennedy was fulfilling a responsibility imposed by his employment by praying during a period in which the District has acknowledged that its coaching staff was free to engage in all manner of private speech. That Mr. Kennedy offered his prayers when students were engaged in other activities like singing the school fight song further suggests that those prayers were not delivered as an address to the team, but instead in his capacity as a private citizen… Nor is it dispositive that Mr. Kennedy’s prayers took place “within the office” environment—here, on the field of play. Instead, what matters is whether Mr. Kennedy offered his prayers while acting within the scope of his duties as a coach. And taken together, both the substance of Mr. Kennedy’s speech and the circumstances surrounding it point to the conclusion that he did not.

In reaching its contrary conclusion, the Ninth Circuit stressed that, as a coach, Mr. Kennedy served as a role model “clothed with the mantle of one who imparts knowledge and wisdom.” … And no doubt they have a point. Teachers and coaches often serve as vital role models. But this argument commits the error of positing an “excessively broad job descriptio[n]” by treating everything teachers and coaches say in the workplace as government speech subject to government control. On this understanding, a school could fire a Muslim teacher for wearing a headscarf in the classroom or prohibit a Christian aide from praying quietly over her lunch in the cafeteria. Likewise, this argument ignores the District Court’s conclusion (and the District’s concession) that Mr. Kennedy’s actual job description left time for a private moment after the game to call home, check a text, socialize, or engage in any manner of secular activities…

IV

Whether one views the case through the lens of the Free Exercise or Free Speech Clause, at this point the burden shifts to the District. Under the Free Exercise Clause, a government entity normally must satisfy at least “strict scrutiny” …

The District, however, asks us to apply to Mr. Kennedy’s claims the more lenient second-step Pickering–Garcetti test, or alternatively intermediate scrutiny. Ultimately, however, it does not matter which standard we apply. The District cannot sustain its burden under any of them.

A

As we have seen, the District argues that its suspension of Mr. Kennedy was essential to avoid a violation of the Establishment Clause…

But how could that be? It is true that this Court and others often refer to the “Establishment Clause,” the “Free Exercise Clause,” and the “Free Speech Clause” as separate units. But the three Clauses appear in the same sentence of the same Amendment… A natural reading of that sentence would seem to suggest the Clauses have “complementary” purposes, not warring ones where one Clause is always sure to prevail.

The District arrived at a different understanding this way. It began with the premise that the Establishment Clause is offended whenever a “reasonable observer” could conclude that the government has “endorse[d]” religion… In this way, the District effectively created its own “vise between the Establishment Clause on one side and the Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses on the other,” placed itself in the middle, and then chose its preferred way out of its self-imposed trap.

To defend its approach, the District relied on Lemon and its progeny. In upholding the District’s actions, the Ninth Circuit followed the same course. And, to be sure, in Lemon this Court attempted a “grand unified theory” for assessing Establishment Clause claims. That approach called for an examination of a law’s purposes, effects, and potential for entanglement with religion. In time, the approach also came to involve estimations about whether a “reasonable observer” would consider the government’s challenged action an “endorsement” of religion.

What the District and the Ninth Circuit overlooked, however, is that the “shortcomings” associated with this “ambitiou[s],” abstract, and ahistorical approach to the Establishment Clause became so “apparent” that this Court long ago abandoned Lemon and its endorsement test offshoot… The Court has explained that these tests “invited chaos” in lower courts, led to “differing results” in materially identical cases, and created a “minefield” for legislators. This Court has since made plain, too, that the Establishment Clause does not include anything like a “modified heckler’s veto, in which . . . religious activity can be proscribed” based on “‘perceptions’” or “‘discomfort.’” An Establishment Clause violation does not automatically follow whenever a public school or other government entity “fail[s] to censor” private religious speech. Nor does the Clause “compel the government to purge from the public sphere” anything an objective observer could reasonably infer endorses or “partakes of the religious.” …

In place of Lemon and the endorsement test, this Court has instructed that the Establishment Clause must be interpreted by “‘reference to historical practices and understandings.’” “‘[T]he line’” that courts and governments “must draw between the permissible and the impermissible” has to “‘accor[d ] with history and faithfully reflec[t] the understanding of the Founding Fathers.’”

… An analysis focused on original meaning and history, this Court has stressed, has long represented the rule rather than some “‘exception’” within the “Court’s Establishment Clause jurisprudence.” … The District and the Ninth Circuit erred by failing to heed this guidance.

B

Perhaps sensing that the primary theory it pursued below rests on a mistaken understanding of the Establishment Clause, the District offers a backup argument in this Court. It still contends that its Establishment Clause concerns trump Mr. Kennedy’s free exercise and free speech rights. But the District now seeks to supply different reasoning for that result. Now, it says, it was justified in suppressing Mr. Kennedy’s religious activity because otherwise it would have been guilty of coercing students to pray…

As it turns out, however, there is a pretty obvious reason why the Ninth Circuit did not adopt this theory in proceedings below: The evidence cannot sustain it… Members of this Court have sometimes disagreed on what exactly qualifies as impermissible coercion in light of the original meaning of the Establishment Clause. But in this case Mr. Kennedy’s private religious exercise did not come close to crossing any line one might imagine separating protected private expression from impermissible government coercion…

… Naturally, Mr. Kennedy’s proposal to pray quietly by himself on the field would have meant some people would have seen his religious exercise. Those close at hand might have heard him too. But learning how to tolerate speech or prayer of all kinds is “part of learning how to live in a pluralistic society,” a trait of character essential to “a tolerant citizenry.” This Court has long recognized as well that “secondary school students are mature enough . . . to understand that a school does not endorse,” let alone coerce them to participate in, “speech that it merely permits on a nondiscriminatory basis.” Of course, some will take offense to certain forms of speech or prayer they are sure to encounter in a society where those activities enjoy such robust constitutional protection. But “[o]ffense . . . does not equate to coercion.”

The District responds that, as a coach, Mr. Kennedy “wielded enormous authority and influence over the students,” and students might have felt compelled to pray alongside him. To support this argument, the District submits that, after Mr. Kennedy’s suspension, a few parents told District employees that their sons had “participated in the team prayers only because they did not wish to separate themselves from the team.”

This reply fails too. Not only does the District rely on hearsay to advance it. For all we can tell, the concerns the District says it heard from parents were occasioned by the locker-room prayers that predated Mr. Kennedy’s tenure or his postgame religious talks, all of which he discontinued at the District’s request. There is no indication in the record that anyone expressed any coercion concerns to the District about the quiet, postgame prayers that Mr. Kennedy asked to continue and that led to his suspension…

The absence of evidence of coercion in this record leaves the District to its final redoubt. Here, the District suggests that any visible religious conduct by a teacher or coach should be deemed—without more and as a matter of law— impermissibly coercive on students. In essence, the District asks us to adopt the view that the only acceptable government role models for students are those who eschew any visible religious expression…

Such a rule would be a sure sign that our Establishment Clause jurisprudence had gone off the rails. In the name of protecting religious liberty, the District would have us suppress it. Rather than respect the First Amendment’s double protection for religious expression, it would have us preference secular activity. Not only could schools fire teachers for praying quietly over their lunch, for wearing a yarmulke to school, or for offering a midday prayer during a break before practice. Under the District’s rule, a school would be required to do so…

… Meanwhile, this case looks very different from those in which this Court has found prayer involving public school students to be problematically coercive. In Lee, this Court held that school officials violated the Establishment Clause by “including [a] clerical membe[r]” who publicly recited prayers “as part of [an] official school graduation ceremony” because the school had “in every practical sense compelled attendance and participation in” a “religious exercise.” In Santa Fe Independent School Dist. v. Doe, the Court held that a school district violated the Establishment Clause by broadcasting a prayer “over the public address system” before each football game. The Court observed that, while students generally were not required to attend games, attendance was required for “cheerleaders, members of the band, and, of course, the team members themselves.”

None of that is true here. The prayers for which Mr. Kennedy was disciplined were not publicly broadcast or recited to a captive audience. Students were not required or expected to participate. And, in fact, none of Mr. Kennedy’s students did participate in any of the three October 2015 prayers that resulted in Mr. Kennedy’s discipline.

C

…

V

Respect for religious expressions is indispensable to life in a free and diverse Republic—whether those expressions take place in a sanctuary or on a field, and whether they manifest through the spoken word or a bowed head. Here, a government entity sought to punish an individual for engaging in a brief, quiet, personal religious observance doubly protected by the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment… The Constitution neither mandates nor tolerates that kind of discrimination…

JUSTICE THOMAS, concurring.

… First, the Court refrains from deciding whether or how public employees’ rights under the Free Exercise Clause may or may not be different from those enjoyed by the general public…

… Second, the Court also does not decide what burden a government employer must shoulder to justify restricting an employee’s religious expression because the District had no constitutional basis for reprimanding Kennedy under any possibly applicable standard of scrutiny…

JUSTICE ALITO, concurring.

The expression at issue in this case is unlike that in any of our prior cases involving the free-speech rights of public employees. Petitioner’s expression occurred while at work but during a time when a brief lull in his duties apparently gave him a few free moments to engage in private activities.

When he engaged in this expression, he acted in a purely private capacity. The Court does not decide what standard applies to such expression under the Free Speech Clause but holds only that retaliation for this expression cannot be justified based on any of the standards discussed. On that understanding, I join the opinion in full.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR, with whom JUSTICE BREYER and JUSTICE KAGAN join, dissenting.

This case is about whether a public school must permit a school official to kneel, bow his head, and say a prayer at the center of a school event. The Constitution does not authorize, let alone require, public schools to embrace this conduct. Since Engel v. Vitale (1962), this Court consistently has recognized that school officials leading prayer is constitutionally impermissible. Official-led prayer strikes at the core of our constitutional protections for the religious liberty of students and their parents, as embodied in both the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment.

The Court now charts a different path, yet again paying almost exclusive attention to the Free Exercise Clause’s protection for individual religious exercise while giving short shrift to the Establishment Clause’s prohibition on state establishment of religion. To the degree the Court portrays petitioner Joseph Kennedy’s prayers as private and quiet, it misconstrues the facts. The record reveals that Kennedy had a longstanding practice of conducting demonstrative prayers on the 50-yard line of the football field. Kennedy consistently invited others to join his prayers and for years led student athletes in prayer at the same time and location. The Court ignores this history…

Today’s decision goes beyond merely misreading the record. The Court overrules Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), and calls into question decades of subsequent precedents that it deems “offshoot[s]” of that decision. In the process, the Court rejects longstanding concerns surrounding government endorsement of religion and replaces the standard for reviewing such questions with a new “history and tradition” test. In addition, while the Court reaffirms that the Establishment Clause prohibits the government from coercing participation in religious exercise, it applies a nearly toothless version of the coercion analysis…

I

As the majority tells it, Kennedy, a coach for the District’s football program, “lost his job” for “pray[ing] quietly while his students were otherwise occupied.” The record before us, however, tells a different story.

A

The District serves approximately 5,057 students and employs 332 teachers and 400 nonteaching personnel in Kitsap County, Washington. The county is home to Bahá’ís, Buddhists, Hindus, Jews, Muslims, Sikhs, Zoroastrians, and many denominations of Christians, as well as numerous residents who are religiously unaffiliated…

… District coaches had to “[a]dhere to [District] policies and administrative regulations” more generally. As relevant here, the District’s policy on “Religious-Related Activities and Practices” provided that “[s]chool staff shall neither encourage or discourage a student from engaging in non-disruptive oral or silent prayer or any other form of devotional activity” and that “[r]eligious services, programs or assemblies shall not be conducted in school facilities during school hours or in connection with any school sponsored or school related activity.”

B

In September 2015, a coach from another school’s football team informed BHS’ principal that Kennedy had asked him and his team to join Kennedy in prayer. The other team’s coach told the principal that he thought it was “‘cool’” that the District “‘would allow [its] coaches to go ahead and invite other teams’ coaches and players to pray after a game.’”

The District initiated an inquiry into whether its policy on Religious-Related Activities and Practices had been violated. It learned that, since his hiring in 2008, Kennedy had been kneeling on the 50-yard line to pray immediately after shaking hands with the opposing team. Kennedy recounted that he initially prayed alone and that he never asked any student to join him. Over time, however, a majority of the team came to join him, with the numbers varying from game to game. Kennedy’s practice evolved into postgame talks in which Kennedy would hold aloft student helmets and deliver speeches with “overtly religious references,” which Kennedy described as prayers, while the players kneeled around him. The District also learned that students had prayed in the past in the locker room prior to games, before Kennedy was hired, but that Kennedy subsequently began leading those prayers too.

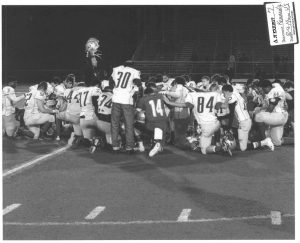

Photograph of J. Kennedy standing in a group of kneeling players.

While the District’s inquiry was pending, its athletic director attended BHS’ September 11, 2015, football game and told Kennedy that he should not be conducting prayers with players. After the game, while the athletic director watched, Kennedy led a prayer out loud, holding up a player’s helmet as the players kneeled around him. While riding the bus home with the team, Kennedy posted on Facebook that he thought he might have just been fired for praying.

On September 17, the District’s superintendent sent Kennedy a letter informing him that leading prayers with students on the field and in the locker room would likely be found to violate the Establishment Clause, exposing the District to legal liability. The District acknowledged that Kennedy had “not actively encouraged, or required, participation” but emphasized that “school staff may not indirectly encourage students to engage in religious activity” or “endors[e]” religious activity; rather, the District explained, staff “must remain neutral” “while performing their job duties.” The District instructed Kennedy that any motivational talks to students must remain secular, “so as to avoid alienation of any team member.” …

Kennedy stopped participating in locker room prayers and, after a game the following day, gave a secular speech. He returned to pray in the stadium alone after his duties were over and everyone had left the stadium, to which the District had no objection. Kennedy then hired an attorney, who, on October 14, sent a letter explaining that Kennedy was “motivated by his sincerely-held religious beliefs to pray following each football game. The letter claimed that the District had required that Kennedy “flee from students if they voluntarily choose to come to a place where he is privately praying during personal time,” referring to the 50-yard line of the football field immediately following the conclusion of a game. Kennedy requested that the District simply issue a “clarif[ication] that the prayer is [Kennedy’s] private speech” and that the District not “interfere” with students joining Kennedy in prayer. The letter further announced that Kennedy would resume his 50-yard-line prayer practice the next day after the October 16 homecoming game.

Before the homecoming game, Kennedy made multiple media appearances to publicize his plans to pray at the 50-yard line, leading to an article in the Seattle News and a local television broadcast about the upcoming homecoming game. In the wake of this media coverage, the District began receiving a large number of emails, letters, and calls, many of them threatening.

The District responded to Kennedy’s letter before the game on October 16. It emphasized that Kennedy’s letter evinced “materia[l] misunderstand[ings]” of many of the facts at issue. For instance, Kennedy’s letter asserted that he had not invited anyone to pray with him; the District noted that that might be true of Kennedy’s September 17 prayer specifically, but that Kennedy had acknowledged inviting others to join him on many previous occasions… the District pointed out that Kennedy “remain[ed] on duty” when his prayers occurred “immediately following completion of the football game, when students are still on the football field, in uniform, under the stadium lights, with the audience still in attendance, and while Mr. Kennedy is still in his District-issued and District-logoed attire.”

The District further noted that “[d]uring the time following completion of the game, until players are released to their parents or otherwise allowed to leave the event, Mr. Kennedy, like all coaches, is clearly on duty and paid to continue supervision of students.” …

On October 16, after playing of the game had concluded, Kennedy shook hands with the opposing team, and as advertised, knelt to pray while most BHS players were singing the school’s fight song. He quickly was joined by coaches and players from the opposing team. Television news cameras surrounded the group. Members of the public rushed the field to join Kennedy, jumping fences to access the field and knocking over student band members. After the game, the District received calls from Satanists who “‘intended to conduct ceremonies on the field after football games if others were allowed to.’” To secure the field and enable subsequent games to continue safely, the District was forced to make security arrangements with the local police and to post signs near the field and place robocalls to parents reiterating that the field was not open to the public…

Photograph of J. Kennedy in a prayer circle (Oct. 16, 2015)

The District sent Kennedy another letter on October 23, explaining that his conduct at the October 16 game was inconsistent with the District’s requirements for two reasons. First, it “drew [him] away from [his] work”; Kennedy had, “until recently, . . . regularly c[o]me to the locker room with the team and other coaches following the game” and had “specific responsibility for the supervision of players in the locker room following games.” Second, his conduct raised Establishment Clause concerns, because “any reasonable observer saw a District employee, on the field only by virtue of his employment with the District, still on duty, under the bright lights of the stadium, engaged in what was clearly, given [his] prior public conduct, overtly religious conduct.” …

Kennedy did not directly respond or suggest a satisfactory accommodation. Instead, his attorneys told the media that he would accept only demonstrative prayer on the 50-yard line immediately after games. During the October 23 and October 26 games, Kennedy again prayed at the 50-yard line immediately following the game, while postgame activities were still ongoing. At the October 23 game, Kennedy kneeled on the field alone with players standing nearby. At the October 26 game, Kennedy prayed surrounded by members of the public, including state representatives who attended the game to support Kennedy. The BHS players, after singing the fight song, joined Kennedy at midfield after he stood up from praying.

Photograph of J. Kennedy in prayer circle (Oct. 26, 2015)

In an October 28 letter, the District notified Kennedy that it was placing him on paid administrative leave for violating its directives at the October 16, October 23, and October 26 games… by kneeling on the field and praying immediately following the games before rejoining the players.

After the issues with Kennedy arose, several parents reached out to the District saying that their children had participated in Kennedy’s prayers solely to avoid separating themselves from the rest of the team. No BHS students appeared to pray on the field after Kennedy’s suspension…

In Kennedy’s annual review, the head coach of the varsity team recommended Kennedy not be rehired because he “failed to follow district policy,” “demonstrated a lack of cooperation with administration,” “contributed to negative relations between parents, students, community members, coaches, and the school district,” and “failed to supervise student-athletes after games due to his interactions with media and community” members.

C

Kennedy then filed suit. He contended, as relevant, that the District violated his rights under the Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses of the First Amendment…

Following discovery, the District Court granted summary judgment to the District.

The Court of Appeals affirmed, explaining that “the facts in the record utterly belie [Kennedy’s] contention that the prayer was personal and private” …

II

Properly understood, this case is not about the limits on an individual’s ability to engage in private prayer at work. This case is about whether a school district is required to allow one of its employees to incorporate a public, communicative display of the employee’s personal religious beliefs into a school event, where that display is recognizable as part of a longstanding practice of the employee ministering religion to students as the public watched. A school district is not required to permit such conduct; in fact, the Establishment Clause prohibits it from doing so.

A

… Taken together, these two Clauses (the Religion Clauses) express the view, foundational to our constitutional system, “that religious beliefs and religious expression are too precious to be either proscribed or prescribed by the State.” Instead, “preservation and transmission of religious beliefs and worship is a responsibility and a choice committed to the private sphere,” which has the “freedom to pursue that mission.”

The Establishment Clause protects this freedom by “command[ing] a separation of church and state.” At its core, this means forbidding “sponsorship, financial support, and active involvement of the sovereign in religious activity.” In the context of public schools, it means that a State cannot use “its public school system to aid any or all religious faiths or sects in the dissemination of their doctrines and ideals.”

Indeed, “[t]he Court has been particularly vigilant in monitoring compliance with the Establishment Clause in elementary and secondary schools.” The reasons motivating this vigilance inhere in the nature of schools themselves and the young people they serve. Two are relevant here.

First, government neutrality toward religion is particularly important in the public-school context given the role public schools play in our society. “‘The public school is at once the symbol of our democracy and the most pervasive means for promoting our common destiny,’” meaning that “‘[i]n no activity of the State is it more vital to keep out divisive forces than in its schools.’” Families “entrust public schools with the education of their children . . . on the understanding that the classroom will not purposely be used to advance religious views that may conflict with the private beliefs of the student and his or her family.” …

Second, schools face a higher risk of unconstitutionally “coerc[ing] . . . support or participat[ion] in religion or its exercise” than other government entities… Moreover, the State exercises that great authority over children, who are uniquely susceptible to “subtle coercive pressure.”

Given the twin Establishment Clause concerns of endorsement and coercion, it is unsurprising that the Court has consistently held integrating prayer into public school activities to be unconstitutional, including when student participation is not a formal requirement or prayer is silent. The Court also has held that incorporating a nondenominational general benediction into a graduation ceremony is unconstitutional. Finally, this Court has held that including prayers in student football games is unconstitutional, even when delivered by students rather than staff and even when students themselves initiated the prayer.

B

Under these precedents, the Establishment Clause violation at hand is clear… Kennedy was on the job as a school official “on government property” when he incorporated a public, demonstrative prayer into “government-sponsored school-related events” as a regularly scheduled feature of those events…

For students and community members at the game, Coach Kennedy was the face and the voice of the District during football games. The timing and location Kennedy selected for his prayers were “clothed in the traditional indicia of school sporting events.” Kennedy spoke from the playing field, which was accessible only to students and school employees, not to the general public. Although the football game itself had ended, the football game events had not; Kennedy himself acknowledged that his responsibilities continued until the players went home. Kennedy’s postgame responsibilities were what placed Kennedy on the 50-yard line in the first place; that was, after all, where he met the opposing team to shake hands after the game. Permitting a school coach to lead students and others he invited onto the field in prayer at a predictable time after each game could only be viewed as a postgame tradition occurring “with the approval of the school administration.”

Kennedy’s prayer practice also implicated the coercion concerns at the center of this Court’s Establishment Clause jurisprudence. This Court has previously recognized a heightened potential for coercion where school officials are involved, as their “effort[s] to monitor prayer will be perceived by the students as inducing a participation they might otherwise reject.” The reasons for fearing this pressure are self-evident. This Court has recognized that students face immense social pressure… Players recognize that gaining the coach’s approval may pay dividends small and large, from extra playing time to a stronger letter of recommendation to additional support in college athletic recruiting…

The record before the Court bears this out…

Kennedy does not defend his longstanding practice of leading the team in prayer out loud on the field as they kneeled around him. Instead, he responds, and the Court accepts, that his highly visible and demonstrative prayer at the last three games before his suspension did not violate the Establishment Clause because these prayers were quiet and thus private. This Court’s precedents, however, do not permit isolating government actions from their context in determining whether they violate the Establishment Clause…

Like the policy change in Santa Fe, Kennedy’s “changed” prayers at these last three games were a clear continuation of a “long-established tradition of sanctioning” school official involvement in student prayers. Students at the three games following Kennedy’s changed practice witnessed Kennedy kneeling at the same time and place where he had led them in prayer for years… Kennedy himself apparently anticipated that his continued prayer practice would draw student participation, requesting that the District agree that it would not “interfere” with students joining him in the future.

Finally, Kennedy stresses that he never formally required students to join him in his prayers. But existing precedents do not require coercion to be explicit, particularly when children are involved…

Thus, the Court has held that the Establishment Clause “will not permit” a school “to exact religious conformity from a student as the price of joining her classmates at a varsity football game.” To uphold a coach’s integration of prayer into the ceremony of a football game, in the context of an established history of the coach inviting student involvement in prayer, is to exact precisely this price from students.

C

As the Court explains, Kennedy did not “shed [his] constitutional rights . . . at the schoolhouse gate” while on duty as a coach. Tinker v. Des Moines (1969). Constitutional rights, however, are not absolutes. Rights often conflict and balancing of interests is often required to protect the separate rights at issue.

… First, as to Kennedy’s free speech claim, Kennedy “accept[ed] certain limitations” on his freedom of speech when he accepted government employment…

As the Court of Appeals below outlined, the District has a strong argument that Kennedy’s speech, formally integrated into the center of a District event, was speech in his official capacity as an employee that is not entitled to First Amendment protections at all. It is unnecessary to resolve this question, however, because, even assuming that Kennedy’s speech was in his capacity as a private citizen, the District’s responsibilities under the Establishment Clause provided “adequate justification” for restricting it.

Similarly, Kennedy’s free exercise claim must be considered in light of the fact that he is a school official and, as such, his participation in religious exercise can create Establishment Clause conflicts. Accordingly, his right to pray at any time and in any manner he wishes while exercising his professional duties is not absolute…

Here, the District’s directive prohibiting Kennedy’s demonstrative speech at the 50-yard line was narrowly tailored to avoid an Establishment Clause violation…

Because the District’s valid Establishment Clause concerns satisfy strict scrutiny, Kennedy’s free exercise claim fails as well.

III

Despite the overwhelming precedents establishing that school officials leading prayer violates the Establishment Clause, the Court today holds that Kennedy’s midfield prayer practice did not violate the Establishment Clause. This decision rests on an erroneous understanding of the Religion Clauses. It also disregards the balance this Court’s cases strike among the rights conferred by the Clauses. The Court relies on an assortment of pluralities, concurrences, and dissents by Members of the current majority to effect fundamental changes in this Court’s Religion Clauses jurisprudence, all the while proclaiming that nothing has changed at all.

A

…

First, the Court describes the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses as “work[ing] in tandem” to “provid[e] overlapping protection for expressive religious activities,” leaving religious speech “doubly protect[ed].” This narrative noticeably (and improperly) sets the Establishment Clause to the side… as this Court has explained … while our Constitution “counsel[s] mutual respect and tolerance,” the Constitution’s vision of how to achieve this end does in fact involve some “singl[ing] out” of religious speech by the government. This is consistent with “the lesson of history that was and is the inspiration for the Establishment Clause, the lesson that in the hands of government what might begin as a tolerant expression of religious views may end in a policy to indoctrinate and coerce.”

Second, the Court contends that the lower courts erred by introducing a false tension between the Free Exercise and Establishment Clauses. The Court, however, has long recognized that these two Clauses, while “express[ing] complementary values,” “often exert conflicting pressures.” …

The Court inaccurately implies that the courts below relied upon a rule that the Establishment Clause must always “prevail” over the Free Exercise Clause. In focusing almost exclusively on Kennedy’s free exercise claim, however, and declining to recognize the conflicting rights at issue, the Court substitutes one supposed blanket rule for another. The proper response where tension arises between the two Clauses is not to ignore it, which effectively silently elevates one party’s right above others…

B

For decades, the Court has recognized that, in determining whether a school has violated the Establishment Clause, “one of the relevant questions is whether an objective observer, acquainted with the text, legislative history, and implementation of the [practice], would perceive it as a state endorsement of prayer in public schools.” The Court now says for the first time that endorsement simply does not matter, and completely repudiates the test established in Lemon. Both of these moves are erroneous and, despite the Court’s assurances, novel.

Start with endorsement. The Court reserves particular criticism for the longstanding understanding that government action that appears to endorse religion violates the Establishment Clause, which it describes as an “offshoot” of Lemon and paints as a “‘modified heckler’s veto” … This is a strawman. Precedent long has recognized that endorsement concerns under the Establishment Clause, properly understood, bear no relation to a “‘heckler’s veto.’” Good News Club itself explained the difference between the two: The endorsement inquiry considers the perspective not of just any hypothetical or uninformed observer experiencing subjective discomfort, but of “‘the reasonable observer’” who is “‘aware of the history and context of the community and forum in which the religious [speech takes place].’” …

Paying heed to these precedents would not “‘purge from the public sphere’ anything an observer could reasonably infer endorses” religion… In short, the endorsement inquiry dictated by precedent is a measured, practical, and administrable one, designed to account for the competing interests present within any given community.

Despite all of this authority, the Court claims that it “long ago abandoned” both the “endorsement test” and this Court’s decision in Lemon…

The Court now goes much further, overruling Lemon entirely and in all contexts. It is wrong to do so… Lemon properly concluded that precedent generally directed consideration of whether the government action had a “secular legislative purpose,” whether its “principal or primary effect must be one that neither advances nor inhibits religion,” and whether in practice it “foster[s] ‘an excessive government entanglement with religion.’” It is true “that rigid application of the Lemon test does not solve every Establishment Clause problem,” but that does not mean that the test has no value…

C

Upon overruling one “grand unified theory,” the Court introduces another: It holds that courts must interpret whether an Establishment Clause violation has occurred mainly “by ‘reference to historical practices and understandings.’” Here again, the Court professes that nothing has changed. In fact, while the Court has long referred to historical practice as one element of the analysis in specific Establishment Clause cases, the Court has never announced this as a general test or exclusive focus…

The Court reserves any meaningful explanation of its history-and-tradition test for another day, content for now to disguise it as established law and move on. It should not escape notice, however, that the effects of the majority’s new rule could be profound. The problems with elevating history and tradition over purpose and precedent are well documented. See Dobbs (2022) (BREYER, SOTOMAYOR, and KAGAN, JJ., dissenting); New York State Rifle & Pistol Assn., Inc. v. Bruen (2022) (BREYER, J., dissenting).

For now, it suffices to say that the Court’s history-and-tradition test offers essentially no guidance for school administrators. If even judges and Justices, with full adversarial briefing and argument tailored to precise legal issues, regularly disagree (and err) in their amateur efforts at history, how are school administrators, faculty, and staff supposed to adapt? How will school administrators exercise their responsibilities to manage school curriculum and events when the Court appears to elevate individuals’ rights to religious exercise above all else? Today’s opinion provides little in the way of answers; the Court simply sets the stage for future legal changes that will inevitably follow the Court’s choice today to upset longstanding rules.

D

Finally, the Court acknowledges that the Establishment Clause prohibits the government from coercing people to engage in religion practice, but its analysis of coercion misconstrues both the record and this Court’s precedents.

The Court claims that the District “never raised coercion concerns” simply because the District conceded that there was “‘no evidence that students [were] directly coerced to pray with Kennedy.’” The Court’s suggestion that coercion must be “direc[t]” to be cognizable under the Establishment Clause is contrary to long-established precedent. The Court repeatedly has recognized that indirect coercion may raise serious establishment concerns, and that “there are heightened concerns with protecting freedom of conscience from subtle coercive pressure in the elementary and secondary public schools.” Tellingly, none of this Court’s major cases involving school prayer concerned school practices that required students to do any more than listen silently to prayers, and some did not even formally require students to listen, instead providing that attendance was not mandatory…

Today’s Court quotes the Lee Court’s remark that enduring others’ speech is “‘part of learning how to live in a pluralistic society.’” The Lee Court, however, expressly concluded, in the very same paragraph, that “[t]his argument cannot prevail” in the school-prayer context because the notion that being subject to a “brief” prayer in school is acceptable “overlooks a fundamental dynamic of the Constitution”: its “specific prohibition on . . . state intervention in religious affairs.”…

The Court also distinguishes Santa Fe because Kennedy’s prayers “were not publicly broadcast or recited to a captive audience.” This misses the point. In Santa Fe, a student council chaplain delivered a prayer over the public-address system before each varsity football game of the season. Students were not required as a general matter to attend the games, but “cheerleaders, members of the band, and, of course, the team members themselves” were, and the Court would have found an “improper effect of coercing those present” even if it “regard[ed] every high school student’s decision to attend . . . as purely voluntary.”

Kennedy’s prayers raise precisely the same concerns. His prayers did not need to be broadcast. His actions spoke louder than his words. His prayers were intentionally, visually demonstrative to an audience aware of their history and no less captive than the audience in Santa Fe, with spectators watching and some players perhaps engaged in a song, but all waiting to rejoin their coach for a postgame talk. Moreover, Kennedy’s prayers had a greater coercive potential because they were delivered not by a student, but by their coach, who was still on active duty for postgame events.

In addition, despite the direct record evidence that students felt coerced to participate in Kennedy’s prayers, the Court nonetheless concludes that coercion was not present in any event because “Kennedy did not seek to direct any prayers to students or require anyone else to participate.” … But nowhere does the Court engage with the unique coercive power of a coach’s actions on his adolescent players.

In any event, the Court makes this assertion only by drawing a bright line between Kennedy’s years-long practice of leading student prayers, which the Court does not defend, and Kennedy’s final three prayers, which BHS students did not join, but student peers from the other teams did. As discussed above, this mode of analysis contravenes precedent by “turn[ing] a blind eye to the context in which [Kennedy’s practice] arose” … The question before the Court is not whether a coach taking a knee to pray on the field would constitute an Establishment Clause violation in any and all circumstances. It is whether permitting Kennedy to continue a demonstrative prayer practice at the center of the football field after years of inappropriately leading students in prayer in the same spot, at that same time, and in the same manner, which led students to feel compelled to join him, violates the Establishment Clause. It does…

To reiterate, the District did not argue, and neither court below held, that “any visible religious conduct by a teacher or coach should be deemed . . . impermissibly coercive on students.” Nor has anyone contended that a coach may never visibly pray on the field. The courts below simply recognized that Kennedy continued to initiate prayers visible to students, while still on duty during school events, under the exact same circumstances as his past practice of leading student prayer. It is unprecedented for the Court to hold that this conduct, taken as a whole, did not raise cognizable coercion concerns…

* * *

The Free Exercise Clause and Establishment Clause are equally integral in protecting religious freedom in our society. The first serves as “a promise from our government,” while the second erects a “backstop that disables our government from breaking it” and “start[ing] us down the path to the past, when [the right to free exercise] was routinely abridged.”

Today, the Court once again weakens the backstop. It elevates one individual’s interest in personal religious exercise, in the exact time and place of that individual’s choosing, over society’s interest in protecting the separation between church and state, eroding the protections for religious liberty for all. Today’s decision is particularly misguided because it elevates the religious rights of a school official, who voluntarily accepted public employment and the limits that public employment entails, over those of his students, who are required to attend school and who this Court has long recognized are particularly vulnerable and deserving of protection. In doing so, the Court sets us further down a perilous path in forcing States to entangle themselves with religion, with all of our rights hanging in the balance. As much as the Court protests otherwise, today’s decision is no victory for religious liberty. I respectfully dissent.

Questions

1. This case shows how framing facts impacts legal judgments. The majority opinion and Sotomayor’s dissent frame the facts and the issue quite differently. What are some of the major differences in how each opinion recites the facts? How do these differences help support their legal arguments?

2. As a matter of legal policy, how much freedom would you grant public employees–or more specifically, public school employees–to engage in religious behavior? How do Coach Kennedy’s actions fit within your preferred framework?

3. The majority opinion argues that the case is primarily about tolerating the religious expression of others when there is no coercion present. In its view, there is no Establishment Clause concern that can justify the district’s action. The dissent disagrees, being concerned that there may be indirect coercion present between the coach and his players and that Kennedy’s prayers might be viewed as an official endorsement of his religion by the school. Who do you feel has the stronger argument, and why?

It’s unclear what the majority’s “history and tradition” test will mean for Establishment Clause doctrine in the long run. What we can say is that at present, the conservative majority values the free exercise rights of school officials more than concerns over the perceived endorsement of religion by the government or indirect coercion. A stronger Free Exercise Clause thus leads to a weaker Establishment Clause.