25

The Death Penalty is Suspended: Furman v. Georgia

Since the 1970s, the constitutionality of the death penalty has been the preeminent issue in Eighth Amendment jurisprudence. As we will see in these materials, however, the question is not only whether the death penalty is constitutional overall (while there has been a persistent level of abolitionist sentiment dating back to the Founding, the answer has been and remains, “yes”), but also when and whether the application of the death penalty creates constitutional problems. On the application question, the Court has frequently intervened, regulating criminal procedure rules in death penalty cases in ways they do not do otherwise. This distinction between capital and non-capital Eighth Amendment jurisprudence is captured by the phrase “death is different,” a remark the justices sometimes make when referring to the gravity and finality of a death sentence.

Unsurprisingly, there were few challenges to the death penalty at the Supreme Court prior to the incorporation of the Eighth Amendment, and such challenges as did arise generally involved whether a particular mode of the death penalty—such as a firing squad or the introduction of the electric chair—was constitutional (the Court upheld both of these particular challenges).

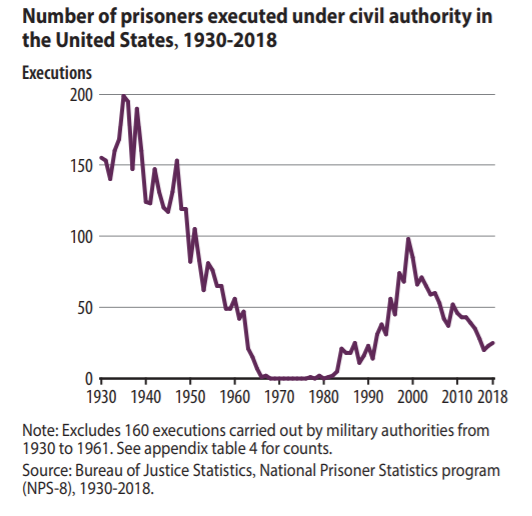

The roots of Furman v. Georgia (1972), a landmark decision in which a majority of the Court suspended the death penalty, lie in the criminal justice politics of the 1950s and 1960s. During this time period, the pendulum of public views on criminal justice and procedure swung in a liberal direction, including increasing disenchantment with the death penalty. While the death penalty remained legal in most states, there was a dramatic drop in both death sentences and executions throughout the country, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1

At the same time, public support for the death penalty dipped to an all-time low during this time period, with opposition to the death penalty briefly outpolling support—something that had never happened before and has not happened since. The increasing rarity of and relative lack of support for the death penalty as the country entered the 1970s partially explains the willingness of five justices to put a halt to all death penalties in the United States in 1972.

Challenges to the death penalty from two litigants from Georgia and one litigant from Texas were consolidated into Furman. Furman’s particular case arose from a challenge to Georgia’s death penalty framework. Furman had been burglarizing a house when he was confronted by a member of the household. During his attempt to escape, he dropped his gun, which discharged and killed a resident of the home. Furman was convicted of felony murder and sentenced to death.

Two important points merit mentioning before we turn to the case materials. First, the Court was unusually splintered in this case. The Court’s decision to overturn Furman’s death sentence was supported by a two-sentence per curiam opinion with no additional rationale offered. This opinion was followed by nine separate opinions: five concurrences and four dissents. The lack of consensus suggested the opinion was vulnerable to being overturned at a later date.

Second, though there were five votes for halting all death penalty sentences temporarily, only two justices—Justice Brennan and Justice Marshall—argued that the death penalty was per se or always unconstitutional. The other three concurrences found fault with the application of the death penalty in the states where the challenges took place, suggesting that their support for the death penalty could be regained should those and other states undergo procedural reforms.

Furman v. Georgia

408 U.S. 238 (1972)

Facts: Furman was stealing items from someone’s home when he was discovered. While fleeing, he tripped and fell, causing the gun he was carrying to go off, killing a resident of the home. He was convicted of felony murder and sentenced to death.

Question: Did Furman’s death sentence violate the Eighth Amendment?

Vote: Yes, 5-4

Concurring opinion: Justice Douglas

Concurring opinion: Justice Brennan

Concurring opinion: Justice Stewart

Concurring opinion: Justice White

Concurring opinion: Justice Marshall

Dissenting opinion: Justice Burger

Dissenting opinion: Justice Blackmun

Dissenting opinion: Justice Powell

Dissenting opinion: Justice Rehnquist

PER CURIAM.

Petitioner … was convicted of murder in Georgia, and was sentenced to death …

The Court holds that the imposition and carrying out of the death penalty in these cases constitute cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. The judgment in each case is therefore reversed insofar as it leaves undisturbed the death sentence imposed, and the cases are remanded for further proceedings.

JUSTICE DOUGLAS, concurring.

… It has been assumed in our decisions that punishment by death is not cruel, unless the manner of execution can be said to be inhuman and barbarous. It is also said in our opinions that the proscription of cruel and unusual punishments “is not fastened to the obsolete, but may acquire meaning as public opinion becomes enlightened by a humane justice.” Weems v. United States. A like statement was made in Trop v. Dulles, that the Eighth Amendment “must draw its meaning from the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.”

The generality of a law inflicting capital punishment is one thing. What may be said of the validity of a law on the books and what may be done with the law in its application do, or may, lead to quite different conclusions.

It would seem to be incontestable that the death penalty inflicted on one defendant is “unusual” if it discriminates against him by reason of his race, religion, wealth, social position, or class, or if it is imposed under a procedure that gives room for the play of such prejudices.

There is evidence that the provision of the English Bill of Rights of 1689, from which the language of the Eighth Amendment was taken, was concerned primarily with selective or irregular application of harsh penalties, and that its aim was to forbid arbitrary and discriminatory penalties of a severe nature…

The words “cruel and unusual” certainly include penalties that are barbaric. But the words, at least when read in light of the English proscription against selective and irregular use of penalties, suggest that it is “cruel and unusual” to apply the death penalty — or any other penalty — selectively to minorities whose numbers are few, who are outcasts of society, and who are unpopular, but whom society is willing to see suffer though it would not countenance general application of the same penalty across the board…

There is increasing recognition of the fact that the basic theme of equal protection is implicit in “cruel and unusual” punishments…” The President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice recently concluded:

Finally, there is evidence that the imposition of the death sentence and the exercise of dispensing power by the courts and the executive follow discriminatory patterns. The death sentence is disproportionately imposed, and carried out on the poor, the Negro, and the members of unpopular groups.

A study of capital cases in Texas from 1924 to 1968 reached the following conclusions: “Application of the death penalty is unequal: most of those executed were poor, young, and ignorant.” …

We cannot say from facts disclosed in these records that these defendants were sentenced to death because they were black. Yet our task is not restricted to an effort to divine what motives impelled these death penalties. Rather, we deal with a system of law and of justice that leaves to the uncontrolled discretion of judges or juries the determination whether defendants committing these crimes should die or be imprisoned. Under these laws, no standards govern the selection of the penalty. People live or die, dependent on the whim of one man or of 12…

Those who wrote the Eighth Amendment knew what price their forebears had paid for a system based not on equal justice, but on discrimination. In those days, the target was not the blacks or the poor, but the dissenters, those who opposed absolutism in government, who struggled for a parliamentary regime, and who opposed governments’ recurring efforts to foist a particular religion on the people. But the tool of capital punishment was used with vengeance against the opposition and those unpopular with the regime. One cannot read this history without realizing that the desire for equality was reflected in the ban against “cruel and unusual punishments” contained in the Eighth Amendment.

In a Nation committed to equal protection of the laws there is no permissible “caste” aspect of law enforcement. Yet we know that the discretion of judges and juries in imposing the death penalty enables the penalty to be selectively applied, feeding prejudices against the accused if he is poor and despised, and lacking political clout, or if he is a member of a suspect or unpopular minority, and saving those who by social position may be in a more protected position. In ancient Hindu, law a Brahman was exempt from capital punishment, and, under that law, “[g]enerally, in the law books, punishment increased in severity as social status diminished.” We have, I fear, taken in practice the same position, partially as a result of making the death penalty…

A law that stated that anyone making more than $50,000 would be exempt from the death penalty would plainly fall, as would a law that in terms said that blacks, those who never went beyond the fifth grade in school, those who made less than $3,000 a year, or those who were unpopular or unstable should be the only people executed. A law which, in the overall view, reaches that result in practice has no more sanctity than a law which in terms provides the same…

JUSTICE BRENNAN, concurring.

… In short, this Court finally adopted the Framers’ view of the Clause as a “constitutional check” to ensure that, “when we come to punishments, no latitude ought to be left, nor dependence put on the virtue of representatives.” That, indeed, is the only view consonant with our constitutional form of government. If the judicial conclusion that a punishment is “cruel and unusual” “depend[ed] upon virtually unanimous condemnation of the penalty at issue,” then, “[l]ike no other constitutional provision, [the Clause’s] only function would be to legitimize advances already made by the other departments and opinions already the conventional wisdom.”

… Judicial enforcement of the Clause, then, cannot be evaded by invoking the obvious truth that legislatures have the power to prescribe punishments for crimes. That is precisely the reason the Clause appears in the Bill of Rights…

Ours would indeed be a simple task were we required merely to measure a challenged punishment against those that history has long condemned. That narrow and unwarranted view of the Clause, however, was left behind with the 19th century. Our task today is more complex. We know “that the words of the [Clause] are not precise, and that their scope is not static.” We know, therefore, that the Clause “must draw its meaning from the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society” …

At bottom, then, the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause prohibits the infliction of uncivilized and inhuman punishments. The State, even as it punishes, must treat its members with respect for their intrinsic worth as human beings. A punishment is “cruel and unusual,” therefore, if it does not comport with human dignity…

The primary principle is that a punishment must not be so severe as to be degrading to the dignity of human beings…

A State may not punish a person for being “mentally ill, or a leper, or . . . afflicted with a venereal disease,” or for being addicted to narcotics. To inflict punishment for having a disease is to treat the individual as a diseased thing, rather than as a sick human being. That the punishment is not severe, “in the abstract,” is irrelevant; “[e]ven one day in prison would be a cruel and unusual punishment for the crime of having a common cold.” Finally, of course, a punishment may be degrading simply by reason of its enormity. A prime example is expatriation, a “punishment more primitive than torture,” Trop v. Dulles, for it necessarily involves a denial by society of the individual’s existence as a member of the human community.

In determining whether a punishment comports with human dignity, we are aided also by a second principle inherent in the Clause — that the State must not [be] arbitrarily severe…

A third principle inherent in the Clause is that a severe punishment must not be unacceptable to contemporary society. Rejection by society, of course, is a strong indication that a severe punishment does not comport with human dignity. In applying this principle, however, we must make certain that the judicial determination is as objective as possible…

The question under this principle, then, is whether there are objective indicators from which a court can conclude that contemporary society considers a severe punishment unacceptable…

The final principle inherent in the Clause is that a severe punishment must not be excessive. A punishment is excessive under this principle if it is unnecessary: the infliction of a severe punishment by the State cannot comport with human dignity when it is nothing more than the pointless infliction of suffering…

The punishment challenged in these cases is death…

There is, first, a textual consideration raised by the Bill of Rights itself. The Fifth Amendment declares that if a particular crime is punishable by death, a person charged with that crime is entitled to certain procedural protections. We can thus infer that the Framers recognized the existence of what was then a common punishment. We cannot, however, make the further inference that they intended to exempt this particular punishment from the express prohibition of the Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause…

The question, then, is whether the deliberate infliction of death is today consistent with the command of the Clause that the State may not inflict punishments that do not comport with human dignity… I will analyze the punishment of death in terms of the principles set out above and the cumulative test to which they lead: it is a denial of human dignity for the State arbitrarily to subject a person to an unusually severe punishment that society has indicated it does not regard as acceptable, and that cannot be shown to serve any penal purpose more effectively than a significantly less drastic punishment. Under these principles and this test, death is today a “cruel and unusual” punishment…

The unusual severity of death is manifested most clearly in its finality and enormity. Death, in these respects, is in a class by itself…

Death is truly an awesome punishment. The calculated killing of a human being by the State involves, by its very nature, a denial of the executed person’s humanity…

In comparison to all other punishments today, then, the deliberate extinguishment of human life by the State is uniquely degrading to human dignity. I would not hesitate to hold, on that ground alone, that death is today a “cruel and unusual” punishment, were it not that death is a punishment of longstanding usage and acceptance in this country. I therefore turn to the second principle — that the State may not arbitrarily inflict an unusually severe punishment.

The outstanding characteristic of our present practice of punishing criminals by death is the infrequency with which we resort to it. The evidence is conclusive that death is not the ordinary punishment for any crime.

There has been a steady decline in the infliction of this punishment in every decade since the 1930’s, the earliest period for which accurate statistics are available. In the 1930’s, executions averaged 167 per year; in the 1940’s, the average was 128; in the 1950’s, it was 72; and in the years 1960-1962, it was 48. There have been a total of 46 executions since then, 36 of them in 1963-1964. Yet our population and the number of capital crimes committed have increased greatly over the past four decades. The contemporary rarity of the infliction of this punishment is thus the end result of a long-continued decline…

When a country of over 200 million people inflicts an unusually severe punishment no more than 50 times a year, the inference is strong that the punishment is not being regularly and fairly applied. To dispel it would indeed require a clear showing of nonarbitrary infliction…

When the rate of infliction is at this low level, it is highly implausible that only the worst criminals or the criminals who commit the worst crimes are selected for this punishment… Furthermore, our procedures in death cases, rather than resulting in the selection of “extreme” cases for this punishment, actually sanction an arbitrary selection… In other words, our procedures are not constructed to guard against the totally capricious selection of criminals for the punishment of death…

The States’ primary claim is that … the threat of death prevents the commission of capital crimes because it deters potential criminals who would not be deterred by the threat of imprisonment. The argument is not based upon evidence that the threat of death is a superior deterrent…

The concern, then, is with a particular type of potential criminal, the rational person who will commit a capital crime knowing that the punishment is long-term imprisonment, which may well be for the rest of his life, but will not commit the crime knowing that the punishment is death. On the face of it, the assumption that such persons exist is implausible…

There is, however, another aspect to the argument that the punishment of death is necessary for the protection of society. The infliction of death, the States urge, serves to manifest the community’s outrage at the commission of the crime. It is, they say, a concrete public expression of moral indignation that inculcates respect for the law and helps assure a more peaceful community. Moreover, we are told, not only does the punishment of death exert this widespread moralizing influence upon community values, it also satisfies the popular demand for grievous condemnation of abhorrent crimes, and thus prevents disorder, lynching, and attempts by private citizens to take the law into their own hands.

The question, however, is not whether death serves these supposed purposes of punishment, but whether death serves them more effectively than imprisonment. There is no evidence whatever that utilization of imprisonment, rather than death, encourages private blood feuds and other disorders. Surely if there were such a danger, the execution of a handful of criminals each year would not prevent it… If capital crimes require the punishment of death in order to provide moral reinforcement for the basic values of the community, those values can only be undermined when death is so rarely inflicted upon the criminals who commit the crimes. Furthermore, it is certainly doubtful that the infliction of death by the State does, in fact, strengthen the community’s moral code; if the deliberate extinguishment of human life has any effect at all, it more likely tends to lower our respect for life and brutalize our values. That, after all, is why we no longer carry out public executions.

There is, then, no substantial reason to believe that the punishment of death, as currently administered, is necessary for the protection of society. The only other purpose suggested, one that is independent of protection for society, is retribution. Shortly stated, retribution in this context means that criminals are put to death because they deserve it.

… The claim must be that, for capital crimes, death alone comports with society’s notion of proper punishment. As administered today, however, the punishment of death cannot be justified as a necessary means of exacting retribution from criminals. When the overwhelming number of criminals who commit capital crimes go to prison, it cannot be concluded that death serves the purpose of retribution more effectively than imprisonment. The asserted public belief that murderers and rapists deserve to die is flatly inconsistent with the execution of a random few…

JUSTICE STEWART, concurring.

… at least two of my Brothers have concluded that the infliction of the death penalty is constitutionally impermissible in all circumstances under the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. Their case is a strong one. But I find it unnecessary to reach the ultimate question they would decide…

… I would say only that I cannot agree that retribution is a constitutionally impermissible ingredient in the imposition of punishment. The instinct for retribution is part of the nature of man, and channeling that instinct in the administration of criminal justice serves an important purpose in promoting the stability of a society governed by law. When people begin to believe that organized society is unwilling or unable to impose upon criminal offenders the punishment they “deserve,” then there are sown the seeds of anarchy — of self-help, vigilante justice, and lynch law…

Instead, the death sentences now before us are the product of a legal system that brings them, I believe, within the very core of the Eighth Amendment’s guarantee against cruel and unusual punishments… In the first place, it is clear that these sentences are “cruel” in the sense that they excessively go beyond, not in degree but in kind, the punishments that the state legislatures have determined to be necessary. In the second place, it is equally clear that these sentences are “unusual” in the sense that the penalty of death is infrequently imposed for murder, and that its imposition for rape is extraordinarily rare. But I do not rest my conclusion upon these two propositions alone.

These death sentences are cruel and unusual in the same way that being struck by lightning is cruel and unusual. For, of all the people convicted of rapes and murders in 1967 and 1968, many just as reprehensible as these, the petitioners are among a capriciously selected random handful upon whom the sentence of death has in fact been imposed. My concurring Brothers have demonstrated that, if any basis can be discerned for the selection of these few to be sentenced to die, it is the constitutionally impermissible basis of race. But racial discrimination has not been proved and I put it to one side. I simply conclude that the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments cannot tolerate the infliction of a sentence of death under legal systems that permit this unique penalty to be so wantonly and so freakishly imposed…

JUSTICE WHITE, concurring.

The facial constitutionality of statutes requiring the imposition of the death penalty for first-degree murder, for more narrowly defined categories of murder, or for rape would present quite different issues under the Eighth Amendment than are posed by the cases before us. In joining the Court’s judgments, therefore, I do not at all intimate that the death penalty is unconstitutional per se or that there is no system of capital punishment that would comport with the Eighth Amendment…

I begin with what I consider a near truism: that the death penalty could so seldom be imposed that it would cease to be a credible deterrent or measurably to contribute to any other end of punishment in the criminal justice system… when imposition of the penalty reaches a certain degree of infrequency, it would be very doubtful that any existing general need for retribution would be measurably satisfied…

The imposition and execution of the death penalty are obviously cruel in the dictionary sense. But the penalty has not been considered cruel and unusual punishment in the constitutional sense because it was thought justified by the social ends it was deemed to serve. At the moment that it ceases realistically to further these purposes, however, the emerging question is whether its imposition in such circumstances would violate the Eighth Amendment. It is my view that it would, for its imposition would then be the pointless and needless extinction of life with only marginal contributions to any discernible social or public purposes. A penalty with such negligible returns to the State would be patently excessive and cruel and unusual punishment violative of the Eighth Amendment…

I must arrive at judgment; and I can do no more than state a conclusion based on 10 years of almost daily exposure to the facts and circumstances of hundreds and hundreds of federal and state criminal cases involving crimes for which death is the authorized penalty. That conclusion, as I have said, is that the death penalty is exacted with great infrequency even for the most atrocious crimes, and that there is no meaningful basis for distinguishing the few cases in which it is imposed from the many cases in which it is not. The short of it is that the policy of vesting sentencing authority primarily in juries — a decision largely motivated by the desire to mitigate the harshness of the law and to bring community judgment to bear on the sentence as well as guilt or innocence — has so effectively achieved its aims that capital punishment within the confines of the statutes now before us has, for all practical purposes, run its course…

JUSTICE MARSHALL, concurring.

… The criminal acts with which we are confronted are ugly, vicious, reprehensible acts. Their sheer brutality cannot and should not be minimized. But we are not called upon to condone the penalized conduct; we are asked only to examine the penalty imposed on each of the petitioners and to determine whether or not it violates the Eighth Amendment…

Perhaps the most important principle in analyzing “cruel and unusual” punishment questions is one that is reiterated again and again in the prior opinions of the Court: i.e., the cruel and unusual language “must draw its meaning from the evolving standard of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.” Thus, a penalty that was permissible at one time in our Nation’s history is not necessarily permissible today.

The fact, therefore, that the Court, or individual Justices, may have in the past expressed an opinion that the death penalty is constitutional is not now binding on us…

First, there are certain punishments that inherently involve so much physical pain and suffering that civilized people cannot tolerate them… Regardless of public sentiment with respect to imposition of one of these punishments in a particular case or at any one moment in history, the Constitution prohibits it. These are punishments that have been barred since the adoption of the Bill of Rights.

Second, there are punishments that are unusual, signifying that they were previously unknown as penalties for a given offense. If these punishments are intended to serve a humane purpose, they may be constitutionally permissible… We need not decide this question here, however, for capital punishment is certainly not a recent phenomenon.

Third, a penalty may be cruel and unusual because it is excessive and serves no valid legislative purpose… these punishments are unconstitutional even though popular sentiment may favor them…. It should also be noted that the “cruel and unusual” language of the Eighth Amendment immediately follows language that prohibits excessive bail and excessive fines. The entire thrust of the Eighth Amendment is, in short, against “that which is excessive.”

Fourth, where a punishment is not excessive and serves a valid legislative purpose, it still may be invalid if popular sentiment abhors it…

It is immediately obvious, then, that since capital punishment is not a recent phenomenon, if it violates the Constitution, it does so because it is excessive or unnecessary, or because it is abhorrent to currently existing moral values…

In order to assess whether or not death is an excessive or unnecessary penalty, it is necessary to consider the reasons why a legislature might select it as punishment for one or more offenses, and examine whether less severe penalties would satisfy the legitimate legislative wants as well as capital punishment. If they would, then the death penalty is unnecessary cruelty, and, therefore, unconstitutional…

The fact that the State may seek retribution against those who have broken its laws does not mean that retribution may then become the State’s sole end in punishing. Our jurisprudence has always accepted deterrence in general, deterrence of individual recidivism, isolation of dangerous persons, and rehabilitation as proper goals of punishment… Retaliation, vengeance, and retribution have been roundly condemned as intolerable aspirations for a government in a free society…

It is plain that the view of the Weems Court was that punishment for the sake of retribution was not permissible under the Eighth Amendment. This is the only view that the Court could have taken if the “cruel and unusual” language were to be given any meaning. Retribution surely underlies the imposition of some punishment on one who commits a criminal act. But the fact that some punishment may be imposed does not mean that any punishment is permissible. If retribution alone could serve as a justification for any particular penalty, then all penalties selected by the legislature would, by definition, be acceptable means for designating society’s moral approbation of a particular act… At times, a cry is heard that morality requires vengeance to evidence society’s abhorrence of the act. But the Eighth Amendment is our insulation from our baser selves…

The most hotly contested issue regarding capital punishment is whether it is better than life imprisonment as a deterrent to crime.

While the contrary position has been argued, it is my firm opinion that the death penalty is a more severe sanction than life imprisonment. Admittedly, there are some persons who would rather die than languish in prison for a lifetime. But, whether or not they should be able to choose death as an alternative is a far different question from that presented here…

It must be kept in mind, then, that the question to be considered is not simply whether capital punishment is a deterrent, but whether it is a better deterrent than life imprisonment.

There is no more complex problem than determining the deterrent efficacy of the death penalty…

Abolitionists attempt to disprove these hypotheses by amassing statistical evidence to demonstrate that there is no correlation between criminal activity and the existence or nonexistence of a capital sanction. Almost all of the evidence involves the crime of murder…

This evidence has its problems, however. One is that there are no accurate figures for capital murders; there are only figures on homicides, and they, of course, include noncapital killings. A second problem is that certain murders undoubtedly are misinterpreted as accidental deaths or suicides, and there is no way of estimating the number of such undetected crimes. A third problem is that not all homicides are reported…

Statistics also show that the deterrent effect of capital punishment is no greater in those communities where executions take place than in other communities. In fact, there is some evidence that imposition of capital punishment may actually encourage crime, rather than deter it…

In sum, the only support for the theory that capital punishment is an effective deterrent is found in the hypotheses with which we began and the occasional stories about a specific individual being deterred from doing a contemplated criminal act…

Despite the fact that abolitionists have not proved non-deterrence beyond a reasonable doubt, they have succeeded in showing by clear and convincing evidence that capital punishment is not necessary as a deterrent to crime in our society. This is all that they must do…

Much of what must be said about the death penalty as a device to prevent recidivism is obvious — if a murderer is executed, he cannot possibly commit another offense. The fact is, however, that murderers are extremely unlikely to commit other crimes, either in prison or upon their release…

Moreover, to the extent that capital punishment is used to encourage confessions and guilty pleas, it is not being used for punishment purposes… Since life imprisonment is sufficient for bargaining purposes, the death penalty is excessive if used for the same purposes.

As for the argument that it is cheaper to execute a capital offender than to imprison him for life, even assuming that such an argument, if true, would support a capital sanction, it is simply incorrect. A disproportionate amount of money spent on prisons is attributable to death row. Condemned men are not productive members of the prison community, although they could be, and executions are expensive. Appeals are often automatic, and courts admittedly spend more time with death cases.

At trial, the selection of jurors is likely to become a costly, time-consuming problem in a capital case, and defense counsel will reasonably exhaust every possible means to save his client from execution, no matter how long the trial takes…

Since no one wants the responsibility for the execution, the condemned man is likely to be passed back and forth from doctors to custodial officials to courts like a ping-pong ball. The entire process is very costly…

There is but one conclusion that can be drawn from all of this — i.e., the death penalty is an excessive and unnecessary punishment that violates the Eighth Amendment. The statistical evidence is not convincing beyond all doubt, but it is persuasive…

While a public opinion poll obviously is of some assistance in indicating public acceptance or rejection of a specific penalty, its utility cannot be very great. This is because whether or not a punishment is cruel and unusual depends not on whether its mere mention “shocks the conscience and sense of justice of the people,” but on whether people who were fully informed as to the purposes of the penalty and its liabilities would find the penalty shocking, unjust, and unacceptable.

In other words, the question with which we must deal is not whether a substantial proportion of American citizens would today, if polled, opine that capital punishment is barbarously cruel, but whether they would find it to be so in the light of all information presently available.

This is not to suggest that, with respect to this test of unconstitutionality, people are required to act rationally; they are not. With respect to this judgment, a violation of the Eighth Amendment is totally dependent on the predictable subjective, emotional reactions of informed citizens.

It has often been noted that American citizens know almost nothing about capital punishment. Some of the conclusions arrived at in the preceding section and the supporting evidence would be critical to an informed judgment on the morality of the death penalty: e.g., that the death penalty is no more effective a deterrent than life imprisonment, that convicted murderers are rarely executed, but are usually sentenced to a term in prison…

This information would almost surely convince the average citizen that the death penalty was unwise, but a problem arises as to whether it would convince him that the penalty was morally reprehensible. This problem arises from the fact that the public’s desire for retribution, even though this is a goal that the legislature cannot constitutionally pursue as is sole justification for capital punishment, might influence the citizenry’s view of the morality of capital punishment. The solution to the problem lies in the fact that no one has ever seriously advanced retribution as a legitimate goal of our society…

But, if this information needs supplementing, I believe that the following facts would serve to convince even the most hesitant of citizens to condemn death as a sanction: capital punishment is imposed discriminatorily against certain identifiable classes of people; there is evidence that innocent people have been executed before their innocence can be proved; and the death penalty wreaks havoc with our entire criminal justice system…

CHIEF JUSTICE BURGER, with whom JUSTICE BLACKMUN, JUSTICE POWELL, and JUSTICE REHNQUIST join, dissenting.

At the outset, it is important to note that only two members of the Court, JUSTICE BRENNAN and JUSTICE MARSHALL, have concluded that the Eighth Amendment prohibits capital punishment for all crimes and under all circumstances…

If we were possessed of legislative power, I would either join with JUSTICE BRENNAN and JUSTICE MARSHALL or, at the very least, restrict the use of capital punishment to a small category of the most heinous crimes. Our constitutional inquiry, however, must be divorced from personal feelings as to the morality and efficacy of the death penalty, and be confined to the meaning and applicability of the uncertain language of the Eighth Amendment… it is essential to our role as a court that we not seize upon the enigmatic character of the guarantee as an invitation to enact our personal predilections into law.

The most persuasive analysis of Parliament’s adoption of the English Bill of Rights of 1689 — the unquestioned source of the Eighth Amendment wording — suggests that the prohibition against “cruel and unusual punishments” was included therein out of aversion to severe punishments not legally authorized and not within the jurisdiction of the courts to impose…

Counsel for petitioners properly concede that capital punishment was not impermissibly cruel at the time of the adoption of the Eighth Amendment. Not only do the records of the debates indicate that the Founding Fathers were limited in their concern to the prevention of torture, but it is also clear from the language of the Constitution itself that there was no thought whatever of the elimination of capital punishment. The opening sentence of the Fifth Amendment is a guarantee that the death penalty not be imposed “unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury.” The Double Jeopardy Clause of the Fifth Amendment is a prohibition against being “twice put in jeopardy of life” for the same offense. Similarly, the Due Process Clause commands “due process of law” before an accused can be “deprived of life, liberty, or property.” Thus, the explicit language of the Constitution affirmatively acknowledges the legal power to impose capital punishment…

In the 181 years since the enactment of the Eighth Amendment, not a single decision of this Court has cast the slightest shadow of a doubt on the constitutionality of capital punishment…

Before recognizing such an instant evolution in the law, it seems fair to ask what factors have changed that capital punishment should now be “cruel” in the constitutional sense as it has not been in the past. It is apparent that there has been no change of constitutional significance in the nature of the punishment itself. Twentieth century modes of execution surely involve no greater physical suffering than the means employed at the time of the Eighth Amendment’s adoption. And although a man awaiting execution must inevitably experience extraordinary mental anguish, no one suggests that this anguish is materially different from that experienced by condemned men in 1791…

However, the inquiry cannot end here. For reasons unrelated to any change in intrinsic cruelty, the Eighth Amendment prohibition cannot fairly be limited to those punishments thought excessively cruel and barbarous at the time of the adoption of the Eighth Amendment. A punishment is inordinately cruel, in the sense we must deal with it in these cases, chiefly as perceived by the society so characterizing it…

The Court’s quiescence in this area can be attributed to the fact that, in a democratic society, legislatures, not courts, are constituted to respond to the will and consequently the moral values of the people…

Accordingly, punishments such as branding and the cutting off of ears, which were commonplace at the time of the adoption of the Constitution, passed from the penal scene without judicial intervention because they became basically offensive to the people, and the legislatures responded to this sentiment.

… I do not suggest that the validity of legislatively authorized punishments presents no justiciable issue under the Eighth Amendment, but, rather, that the primacy of the legislative role narrowly confines the scope of judicial inquiry. Whether or not provable, and whether or not true at all times, in a democracy, the legislative judgment is presumed to embody the basic standards of decency prevailing in the society. This presumption can only be negated by unambiguous and compelling evidence of legislative default.

There are no obvious indications that capital punishment offends the conscience of society to such a degree that our traditional deference to the legislative judgment must be abandoned. It is not a punishment, such as burning at the stake, that everyone would ineffably find to be repugnant to all civilized standards. Nor is it a punishment so roundly condemned that only a few aberrant legislatures have retained it on the statute books. Capital punishment is authorized by statute in 40 States, the District of Columbia, and in the federal courts for the commission of certain crimes. On four occasions in the last 11 years, Congress has added to the list of federal crimes punishable by death…

Counsel for petitioners rely on a different body of empirical evidence. They argue, in effect, that the number of cases in which the death penalty is imposed, as compared with the number of cases in which it is statutorily available, reflects a general revulsion toward the penalty that would lead to its repeal if only it were more generally and widely enforced…

It is argued that, in those capital cases where juries have recommended mercy, they have given expression to civilized values and effectively renounced the legislative authorization for capital punishment. At the same time, it is argued that, where juries have made the awesome decision to send men to their deaths, they have acted arbitrarily and without sensitivity to prevailing standards of decency. This explanation for the infrequency of imposition of capital punishment is unsupported by known facts, and is inconsistent in principle with everything this Court has ever said about the functioning of juries in capital cases…

Given the general awareness that death is no longer a routine punishment for the crimes for which it is made available, it is hardly surprising that juries have been increasingly meticulous in their imposition of the penalty. But to assume from the mere fact of relative infrequency that only a random assortment of pariahs are sentenced to death is to cast grave doubt on the basic integrity of our jury system.

It would, of course, be unrealistic to assume that juries have been perfectly consistent in choosing the cases where the death penalty is to be imposed, for no human institution performs with perfect consistency. There are doubtless prisoners on death row who would not be there had they been tried before a different jury or in a different State. In this sense, their fate has been controlled by a fortuitous circumstance. However, this element of fortuity does not stand as an indictment either of the general functioning of juries in capital cases or of the integrity of jury decisions in individual cases. There is no empirical basis for concluding that juries have generally failed to discharge in good faith the responsibility … of choosing between life and death in individual cases according to the dictates of community values.

The rate of imposition of death sentences falls far short of providing the requisite unambiguous evidence that the legislatures of 40 States and the Congress have turned their backs on current or evolving standards of decency in continuing to make the death penalty available…

Capital punishment has also been attacked as violative of the Eighth Amendment on the ground that it is not needed to achieve legitimate penal aims, and is thus “unnecessarily cruel.” As a pure policy matter, this approach has much to recommend it, but it seeks to give a dimension to the Eighth Amendment that it was never intended to have and promotes a line of inquiry that this Court has never before pursued.

The Eighth Amendment, as I have noted, was included in the Bill of Rights to guard against the use of torturous and inhuman punishments, not those of limited efficacy…

By pursuing the necessity approach, it becomes even more apparent that it involves matters outside the purview of the Eighth Amendment. Two of the several aims of punishment are generally associated with capital punishment — retribution and deterrence. It is argued that retribution can be discounted because that, after all, is what the Eighth Amendment seeks to eliminate. There is no authority suggesting that the Eighth Amendment was intended to purge the law of its retributive elements… It would be reading a great deal into the Eighth Amendment to hold that the punishments authorized by legislatures cannot constitutionally reflect a retributive purpose.

The less esoteric but no less controversial question is whether the death penalty acts as a superior deterrent. Those favoring abolition find no evidence that it does. Those favoring retention start from the intuitive notion that capital punishment should act as the most effective deterrent, and note that there is no convincing evidence that it does not. Escape from this empirical stalemate is sought by placing the burden of proof on the States and concluding that they have failed to demonstrate that capital punishment is a more effective deterrent than life imprisonment… If it were proper to put the States to the test of demonstrating the deterrent value of capital punishment, we could just as well ask them to prove the need for life imprisonment or any other punishment. Yet I know of no convincing evidence that life imprisonment is a more effective deterrent than 20 years’ imprisonment, or even that a $10 parking ticket is a more effective deterrent than a $5 parking ticket. In fact, there are some who go so far as to challenge the notion that any punishments deter crime. If the States are unable to adduce convincing proof rebutting such assertions, does it then follow that all punishments are suspect as being “cruel and unusual” within the meaning of the Constitution? On the contrary, I submit that the questions raised by the necessity approach are beyond the pale of judicial inquiry under the Eighth Amendment…

The actual scope of the Court’s ruling … is not entirely clear. This much, however, seems apparent: if the legislatures are to continue to authorize capital punishment for some crimes, juries and judges can no longer be permitted to make the sentencing determination in the same manner they have in the past…

[The concurring opinions] suggest that capital punishment can be made to satisfy Eighth Amendment values if its rate of imposition is somehow multiplied; it seemingly follows that the flexible sentencing system created by the legislatures, and carried out by juries and judges, has yielded more mercy than the Eighth Amendment can stand. The implications of this approach are mildly ironical…

While I would not undertake to make a definitive statement as to the parameters of the Court’s ruling, it is clear that, if state legislatures and the Congress wish to maintain the availability of capital punishment, significant statutory changes will have to be made. Since the two pivotal concurring opinions turn on the assumption that the punishment of death is now meted out in a random and unpredictable manner, legislative bodies may seek to bring their laws into compliance with the Court’s ruling by providing standards for juries and judges to follow in determining the sentence in capital cases or by more narrowly defining the crimes for which the penalty is to be imposed…

Since there is no majority of the Court on the ultimate issue presented in these cases, the future of capital punishment in this country has been left in an uncertain limbo. Rather than providing a final and unambiguous answer on the basic constitutional question, the collective impact of the majority’s ruling is to demand an undetermined measure of change from the various state legislatures and the Congress…

The world-wide trend toward limiting the use of capital punishment, a phenomenon to which we have been urged to give great weight, hardly points the way to a judicial solution in this country under a written Constitution. Rather, the change has generally come about through legislative action…

JUSTICE BLACKMUN, dissenting.

Cases such as these provide for me an excruciating agony of the spirit. I yield to no one in the depth of my distaste, antipathy, and, indeed, abhorrence, for the death penalty, with all its aspects of physical distress and fear and of moral judgment exercised by finite minds. That distaste is buttressed by a belief that capital punishment serves no useful purpose that can be demonstrated…

Were I a legislator, I would vote against the death penalty for the policy reasons argued by counsel for the respective petitioners and expressed and adopted in the several opinions filed by the Justices who vote to reverse these judgments…

The several concurring opinions acknowledge, as they must, that, until today, capital punishment was accepted and assumed as not unconstitutional per se under the Eighth Amendment or the Fourteenth Amendment…

Suddenly, however, the course of decision is now the opposite way, with the Court evidently persuaded that somehow the passage of time has taken us to a place of greater maturity and outlook…

The Court has recognized, and I certainly subscribe to the proposition, that the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause “may acquire meaning as public opinion becomes enlightened by a humane justice.”

My problem, however, as I have indicated, is the suddenness of the Court’s perception of progress in the human attitude since decisions of only a short while ago…

It is comforting to relax in the thoughts perhaps the rationalizations — that this is the compassionate decision for a maturing society; that this is the moral and the “right” thing to do; that thereby we convince ourselves that we are moving down the road toward human decency; that we value life even though that life has taken another or others or has grievously scarred another or others and their families; and that we are less barbaric than we were in 1879, or in 1890, or in 1910, or in 1947, or in 1958, or in 1963, or a year ago…

This, for me, is good argument, and it makes some sense. But it is good argument and it makes sense only in a legislative and executive way, and not as a judicial expedient… The authority should not be taken over by the judiciary in the modern guise of an Eighth Amendment issue…

JUSTICE POWELL, with whom THE CHIEF JUSTICE, JUSTICE BLACKMUN, and JUSTICE REHNQUIST join, dissenting.

… Although the central theme of petitioners’ presentations in these cases is that the imposition of the death penalty is per se unconstitutional, only two of today’s opinions explicitly conclude that so sweeping a determination is mandated by the Constitution…

In terms of the constitutional role of this Court, the impact of the majority’s ruling is all the greater because the decision encroaches upon an area squarely within the historic prerogative of the legislative branch — both state and federal — to protect the citizenry through the designation of penalties for prohibitable conduct. It is the very sort of judgment that the legislative branch is competent to make, and for which the judiciary is ill-equipped…

… Nor are “cruel and unusual punishments” and “due process of law” static concepts whose meaning and scope were sealed at the time of their writing. They were designed to be dynamic and to gain meaning through application to specific circumstances, many of which were not contemplated by their authors. While flexibility in the application of these broad concepts is one of the hallmarks of our system of government, the Court is not free to read into the Constitution a meaning that is plainly at variance with its language. Both the language of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments and the history of the Eighth Amendment confirm beyond doubt that the death penalty was considered to be a constitutionally permissible punishment…

… we are not asked to consider the permissibility of any of the several methods employed in carrying out the death sentence. Nor are we asked, at least as part of the core submission in these cases, to determine whether the penalty might be a grossly excessive punishment for some specific criminal conduct. Either inquiry would call for a discriminating evaluation of particular means, or of the relationship between particular conduct and its punishment. Petitioners’ principal argument goes far beyond the traditional process of case-by-case inclusion and exclusion. Instead the argument insists on an unprecedented constitutional rule of absolute prohibition of capital punishment for any crime, regardless of its depravity and impact on society…

… where, as here, the language of the applicable provision provides great leeway, and where the underlying social policies are felt to be of vital importance, the temptation to read personal preference into the Constitution is understandably great. It is too easy to propound our subjective standards of wise policy under the rubric of more or less universally held standards of decency…

How much graver is that duty when we are not asked to pass on the constitutionality of a single penalty under the facts of a single case, but instead are urged to overturn the legislative judgments of 40 state legislatures as well as those of Congress…

The burden of seeking so sweeping a decision against such formidable obstacles is almost insuperable. Viewed from this perspective, as I believe it must be, the case against the death penalty falls far short…

One must conclude, contrary to petitioners’ submission, that the indicators most likely to reflect the public’s view — legislative bodies, state referenda and the juries which have the actual responsibility — do not support the contention that evolving standards of decency require total abolition of capital punishment. Indeed, the weight of the evidence indicates that the public generally has not accepted either the morality or the social merit of the views so passionately advocated by the articulate spokesmen for abolition…

… [we are told] … in effect, not that capital punishment presently offends our citizenry, but that the public would be offended if the penalty were enforced in a nondiscriminatory manner against a significant percentage of those charged with capital crimes, and if the public were thereby made aware of the moral issues surrounding capital punishment. Rather than merely registering the objective indicators on a judicial balance, we are asked ultimately to rest a far-reaching constitutional determination on a prediction regarding the subjective judgments of the mass of our people under hypothetical assumptions that may or may not be realistic…

Apart from the impermissibility of basing a constitutional judgment of this magnitude on such speculative assumptions, the argument suffers from other defects. If, as petitioners urge, we are to engage in speculation, it is not at all certain that the public would experience deep-felt revulsion if the States were to execute as many sentenced capital offenders this year as they executed in the mid-1930’s…

As JUSTICE MARSHALL’s opinion today demonstrates, the argument does have a more troubling aspect. It is his contention that if the average citizen were aware of the disproportionate burden of capital punishment borne by the “poor, the ignorant, and the underprivileged,” he would find the penalty “shocking to his conscience and sense of justice,” and would not stand for its further use. This argument, like the apathy rationale, calls for further speculation on the part of the Court. It also illuminates the quicksands upon which we are asked to base this decision. Indeed, the two contentions seem to require contradictory assumptions regarding the public’s moral attitude toward capital punishment…

Certainly the claim is justified that this criminal sanction falls more heavily on the relatively impoverished and underprivileged elements of society. The “have-nots” in every society always have been subject to greater pressure to commit crimes and to fewer constraints than their more affluent fellow citizens. This is, indeed, a tragic byproduct of social and economic deprivation, but it is not an argument of constitutional proportions under the Eighth or Fourteenth Amendment. The same discriminatory impact argument could be made with equal force and logic with respect to those sentenced to prison terms… The root causes of the higher incidence of criminal penalties on “minorities and the poor” will not be cured by abolishing the system of penalties…

Although not presented by any of the petitioners today, a different argument, premised on the Equal Protection Clause, might well be made. If a Negro defendant, for instance, could demonstrate that members of his race were being singled out for more severe punishment than others charged with the same offense, a constitutional violation might be established…

JUSTICE REHNQUIST, with whom THE CHIEF JUSTICE, JUSTICE BLACKMUN, and JUSTICE POWELL join, dissenting.

The Court’s judgments today strike down a penalty that our Nation’s legislators have thought necessary since our country was founded…

Rigorous attention to the limits of this Court’s authority is likewise enjoined because of the natural desire that beguiles judges along with other human beings into imposing their own views of goodness, truth, and justice upon others. Judges differ only in that they have the power, if not the authority, to enforce their desires. This is doubtless why nearly two centuries of judicial precedent from this Court counsel the sparing use of that power. The most expansive reading of the leading constitutional cases does not remotely suggest that this Court has been granted a roving commission, either by the Founding Fathers or by the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment, to strike down laws that are based upon notions of policy or morality suddenly found unacceptable by a majority of this Court…

A separate reason for deference to the legislative judgment is the consequence of human error on the part of the judiciary with respect to the constitutional issue before it. Human error there is bound to be, judges being men and women, and men and women being what they are. But an error in mistakenly sustaining the constitutionality of a particular enactment, while wrongfully depriving the individual of a right secured to him by the Constitution, nonetheless does so by simply letting stand a duly enacted law of a democratically chosen legislative body. The error resulting from a mistaken upholding of an individual’s constitutional claim against the validity of a legislative enactment is a good deal more serious. For the result in such a case is not to leave standing a law duly enacted by a representative assembly, but to impose upon the Nation the judicial fiat of a majority of a court of judges whose connection with the popular will is remote, at best…

I conclude that this decision holding unconstitutional capital punishment is not an act of judgment, but rather an act of will…

Questions

1. The concurring opinions point to how rare it was for someone to receive the death penalty at the time of the case, even for the worst of homicides. Juries had almost complete control over the sentencing process, making a death sentence unacceptably random at best or guided by racial or other prejudice at worst. To these justices, this rarity of use was a sign of unacceptable arbitrariness.

The dissenting opinions, by contrast, argue that the decreasing number of death sentences was a good thing. Rather than being taken as evidence that the death penalty was disfavored or arbitrarily assigned, it was instead viewed as juries only applying the death penalty in circumstances where they felt it absolutely required.

Which of these viewpoints do you find more convincing? What additional information would you like to know regarding this debate in order to help you decide?

2. Justice Marshall argues that retribution—or revenge, in his framing—is not a constitutional justification for the death penalty. In his words, “Retaliation, vengeance, and retribution have been roundly condemned as intolerable aspirations for a government in a free society.”

Justice Stewart—while agreeing with Marshall that the current application of the death penalty is unconstitutional—disagrees. He says “when people begin to believe that organized society is unwilling or unable to impose upon criminal offenders the punishment they ‘deserve,’ then there are sown the seeds of anarchy — of self-help, vigilante justice, and lynch law.”

Who has the better argument?

3. When it comes to deterrence, both sides agree that it’s unclear whether the death penalty deters crime relative to a life sentence. They mainly disagree regarding who should bear the burden of proof.

Justice Marshall, for example, argues that states shouldn’t be able to rely on deterrence as a penological justification if they can’t prove it works.

The dissenters respond that whether deterrence “works” is a complex empirical question that legislatures, not courts, should decide. Unless there is clear evidence that deterrence doesn’t work, states should have the latitude to make decisions.

Who do you side with on this question?

Killing someone while in the midst of committing a separate felony, such as robbery or arson. Felony murder has been designated as a capital crime in many states, even though, typically, the killer did not specifically intend the victim's death.