10 Unprotected Categories: Defamation and other Torts

Foundations of Defamation Doctrine

What does this have to do with the freedom of speech? In short, politicians or the very wealthy can successfully use the threat of defamation lawsuits to silence criticism or discourage reporting on their activities. This was particularly the case in states with strict liability standards. Even for skilled, ethical reporters and news media, mistakes are inevitable. Under strict liability, any false statement of fact—no matter how carefully the reporter behaved—could lead to damages if a jury sympathizes with the plaintiff. To paraphrase, libel and slander torts can create a regime of “censorship by lawsuit” that could be just as damaging to the goals of free speech as the threat of criminal punishment.

As with many other areas of civil liberties law, the Court began to take these concerns more seriously in the 1960s, in reaction to legal attacks on the Civil Rights movement. Like any other set of interest groups, civil rights groups relied on the media to broadcast their message and advertise their values, events, and struggles. Such messages sometimes contained depictions of police brutality or other types of oppression in response to civil rights demonstrations or protests. Relying on the strict liability standards for libel present in several states, opponents of civil rights would comb these messages for factual errors, encourage individuals who could claim some sort of reputational harm to sue them in state court, and receive hefty awards with the blessing of all-white juries. Such awards could bankrupt smaller civil rights groups or publications, and thus served as a type of private censorship on those who wished to cover civil rights or draw attention to Jim Crow abuses.

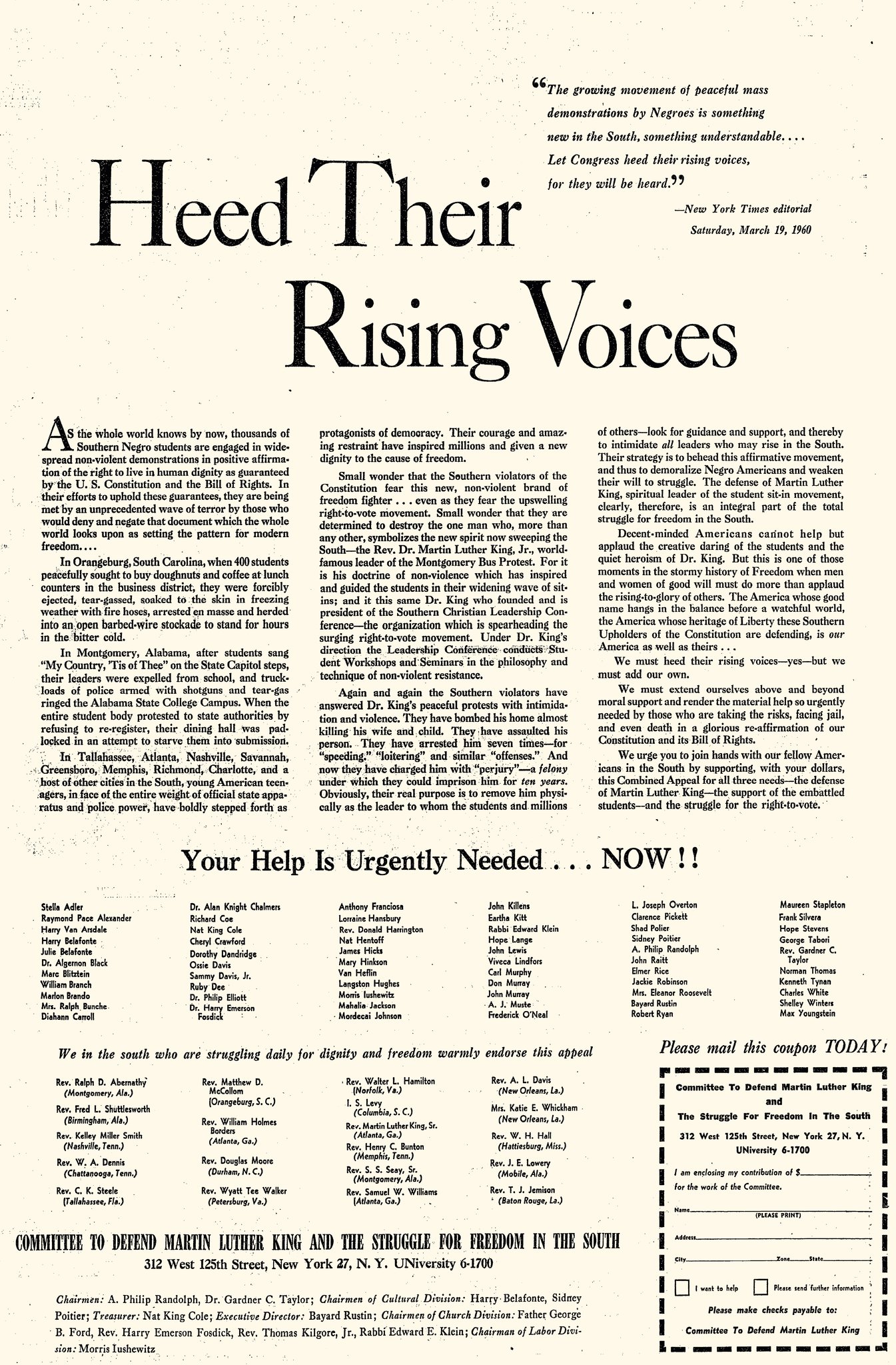

The Supreme Court addressed this practice in New York Times v. Sullivan (1964), a case that constitutionalized libel law and still stands as the foundation for defamation doctrine in the United States. The case began when the New York Times ran a full-page ad (see Figure 1, below) paid for by civil rights advocates who supported Dr. King’s efforts in Montgomery, Alabama.

The advertisement did contain factual errors. For example, the ad falsely said that a campus dining hall had been padlocked, and stated that Dr. King had been arrested seven times (when the correct number was four). In response to the advertisement, Sullivan—a city commissioner in Montgomery—sued both the activists and the New York Times for defamation, arguing that while not mentioned in the ad by name, his duties included supervision of the police. The inaccuracies in the advertisement, he claimed, therefore hurt his reputation. An Alabama jury agreed, awarding him $500,000 in damages; the state supreme court upheld the award.

Figure 1: The Advertisement in New York Times v. Sullivan

The Times appealed to the Supreme Court, which unanimously struck down Alabama’s strict liability standard and revolutionized defamation law.

New York Times v. Sullivan

376 U.S. 254 (1964)

Facts: The New York Times published an advertisement (paid for by a civil rights group) that described police action against students engaged in a civil rights demonstration. Sullivan, a Montgomery city commissioner who had supervisory power over the police, cited errors in the advertisement and sued both those who commissioned the ad and the New York Times for libel, arguing his reputation had been damaged by its contents. Under Alabama’s strict liability standard for libel, a jury awarded Sullivan $500,000. After the Alabama Supreme Court upheld the award, the Times appealed to the Supreme Court.

Question: Did Alabama’s libel law violate the First Amendment’s free speech clause?

Vote: Yes, 9-0

For the Court: Justice Brennan

Concurring opinion: Justice Black

Concurring opinion: Justice Goldberg

JUSTICE BRENNAN delivered the opinion of the Court.

We are required in this case to determine for the first time the extent to which the constitutional protections for speech and press limit a State’s power to award damages in a libel action brought by a public official against critics of his official conduct.

Respondent L. B. Sullivan is one of the three elected Commissioners of the City of Montgomery, Alabama. He testified that he was “Commissioner of Public Affairs, and the duties are supervision of the Police Department, Fire Department, Department of Cemetery and Department of Scales.”

He brought this civil libel action against the four individual petitioners, who are Negroes and Alabama clergymen, and against petitioner the New York Times Company, a New York corporation which publishes the New York Times, a daily newspaper. A jury in the Circuit Court of Montgomery County awarded him damages of $500,000, the full amount claimed, against all the petitioners, and the Supreme Court of Alabama affirmed.

Respondent’s complaint alleged that he had been libeled by statements in a full-page advertisement that was carried in the New York Times on March 29, 1960. Entitled “Heed Their Rising Voices,” the advertisement began by stating that,

As the whole world knows by now, thousands of Southern Negro students are engaged in widespread nonviolent demonstrations in positive affirmation of the right to live in human dignity as guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

It went on to charge that,

in their efforts to uphold these guarantees, they are being met by an unprecedented wave of terror by those who would deny and negate that document which the whole world looks upon as setting the pattern for modern freedom…

… Of the 10 paragraphs of text in the advertisement, the third and a portion of the sixth were the basis of respondent’s claim of libel. They read as follows:

Third paragraph:

In Montgomery, Alabama, after students sang ‘My Country, ‘Tis of Thee’ on the State Capitol steps, their leaders were expelled from school, and truckloads of police armed with shotguns and tear-gas ringed the Alabama State College Campus. When the entire student body protested to state authorities by refusing to reregister, their dining hall was padlocked in an attempt to starve them into submission.

Sixth paragraph:

Again and again, the Southern violators have answered Dr. King’s peaceful protests with intimidation and violence. They have bombed his home, almost killing his wife and child. They have assaulted his person. They have arrested him seven times — for ‘speeding,’ ‘loitering’ and similar ‘offenses.’ And now they have charged him with ‘perjury’ — a felony under which they could imprison him for ten years…

Although neither of these statements mentions respondent by name, he contended that the word “police” in the third paragraph referred to him as the Montgomery Commissioner who supervised the Police Department, so that he was being accused of “ringing” the campus with police. He further claimed that the paragraph would be read as imputing to the police, and hence to him, the padlocking of the dining hall in order to starve the students into submission. As to the sixth paragraph, he contended that, since arrests are ordinarily made by the police, the statement “They have arrested [Dr. King] seven times” would be read as referring to him…

It is uncontroverted that some of the statements contained in the two paragraphs were not accurate descriptions of events which occurred in Montgomery…

Respondent made no effort to prove that he suffered actual pecuniary loss as a result of the alleged libel…

Alabama law denies a public officer recovery of punitive damages in a libel action brought on account of a publication concerning his official conduct unless he first makes a written demand for a public retraction and the defendant fails or refuses to comply… The Times did not publish a retraction in response to the demand, but wrote respondent a letter stating, among other things, that “we . . . are somewhat puzzled as to how you think the statements in any way reflect on you,” and “you might, if you desire, let us know in what respect you claim that the statements in the advertisement reflect on you.” Respondent filed this suit a few days later without answering the letter…

Because of the importance of the constitutional issues involved, we granted the separate petitions for certiorari of the individual petitioners and of the Times. We reverse the judgment. We hold that the rule of law applied by the Alabama courts is constitutionally deficient for failure to provide the safeguards for freedom of speech and of the press that are required by the First and Fourteenth Amendments in a libel action brought by a public official against critics of his official conduct. We further hold that, under the proper safeguards, the evidence presented in this case is constitutionally insufficient to support the judgment for respondent.

I

We may dispose at the outset of two grounds asserted to insulate the judgment of the Alabama courts from constitutional scrutiny. The first is the proposition relied on by the State Supreme Court — that “The Fourteenth Amendment is directed against State action, and not private action.” That proposition has no application to this case. Although this is a civil lawsuit between private parties, the Alabama courts have applied a state rule of law which petitioners claim to impose invalid restrictions on their constitutional freedoms of speech and press. It matters not that that law has been applied in a civil action and that it is common law only, though supplemented by statute.

The second contention is that the constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech and of the press are inapplicable here, at least so far as the Times is concerned, because the allegedly libelous statements were published as part of a paid, “commercial” advertisement. The reliance is wholly misplaced…

The publication here was not a “commercial” advertisement … It communicated information, expressed opinion, recited grievances, protested claimed abuses, and sought financial support on behalf of a movement whose existence and objectives are matters of the highest public interest and concern. That the Times was paid for publishing the advertisement is as immaterial in this connection as is the fact that newspapers and books are sold…

II

Under Alabama law, as applied in this case, a publication is “libelous per se” if the words “tend to injure a person . . . in his reputation” or to “bring [him] into public contempt” … Once “libel per se” has been established, the defendant has no defense as to stated facts unless he can persuade the jury that they were true in all their particulars…

The question before us is whether this rule of liability, as applied to an action brought by a public official against critics of his official conduct, abridges the freedom of speech and of the press that is guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

Respondent relies heavily, as did the Alabama courts, on statements of this Court to the effect that the Constitution does not protect libelous publications… None of the cases sustained the use of libel laws to impose sanctions upon expression critical of the official conduct of public officials….

In deciding the question now, we are compelled by neither precedent nor policy to give any more weight to the epithet “libel” than we have to other “mere labels” of state law… libel can claim no talismanic immunity from constitutional limitations. It must be measured by standards that satisfy the First Amendment.

The general proposition that freedom of expression upon public questions is secured by the First Amendment has long been settled by our decisions. The constitutional safeguard, we have said, “was fashioned to assure unfettered interchange of ideas for the bringing about of political and social changes desired by the people.” …

Thus, we consider this case against the background of a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.

The present advertisement, as an expression of grievance and protest on one of the major public issues of our time, would seem clearly to qualify for the constitutional protection. The question is whether it forfeits that protection by the falsity of some of its factual statements and by its alleged defamation of respondent.

Authoritative interpretations of the First Amendment guarantees have consistently refused to recognize an exception for any test of truth — whether administered by judges, juries, or administrative officials — and especially one that puts the burden of proving truth on the speaker. The constitutional protection does not turn upon “the truth, popularity, or social utility of the ideas and beliefs which are offered.” As Madison said, “Some degree of abuse is inseparable from the proper use of everything, and in no instance is this more true than in that of the press.” …

What a State may not constitutionally bring about by means of a criminal statute is likewise beyond the reach of its civil law of libel. The fear of damage awards under a rule such as that invoked by the Alabama courts here may be markedly more inhibiting than the fear of prosecution under a criminal statute. Alabama, for example, has a criminal libel law … Presumably, a person charged with violation of this statute enjoys ordinary criminal law safeguards such as the requirements of an indictment and of proof beyond a reasonable doubt. These safeguards are not available to the defendant in a civil action. The judgment awarded in this case — without the need for any proof of actual pecuniary loss — was one thousand times greater than the maximum fine provided by the Alabama criminal statute …

And since there is no double jeopardy limitation applicable to civil lawsuits, this is not the only judgment that may be awarded against petitioners for the same publication. Whether or not a newspaper can survive a succession of such judgments, the pall of fear and timidity imposed upon those who would give voice to public criticism is an atmosphere in which the First Amendment freedoms cannot survive…

A rule compelling the critic of official conduct to guarantee the truth of all his factual assertions — and to do so on pain of libel judgments virtually unlimited in amount — leads to a comparable “self-censorship.” Allowance of the defense of truth, with the burden of proving it on the defendant, does not mean that only false speech will be deterred… Under such a rule, would-be critics of official conduct may be deterred from voicing their criticism, even though it is believed to be true and even though it is, in fact, true, because of doubt whether it can be proved in court or fear of the expense of having to do so…. The rule thus dampens the vigor and limits the variety of public debate. It is inconsistent with the First and Fourteenth Amendments. The constitutional guarantees require, we think, a federal rule that prohibits a public official from recovering damages for a defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves that the statement was made with “actual malice” — that is, with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not…

III

We hold today that the Constitution delimits a State’s power to award damages for libel in actions brought by public officials against critics of their official conduct. Since this is such an action, the rule requiring proof of actual malice is applicable. While Alabama law apparently requires proof of actual malice for an award of punitive damages, where general damages are concerned malice is “presumed.” Such a presumption is inconsistent with the federal rule… “

… Applying these standards, we consider that the proof presented to show actual malice lacks the convincing clarity which the constitutional standard demands, and hence that it would not constitutionally sustain the judgment for respondent under the proper rule of law… As to the Times, we similarly conclude that the facts do not support a finding of actual malice…

The statement does not indicate malice at the time of the publication; even if the advertisement was not “substantially correct” — although respondent’s own proofs tend to show that it was — that opinion was at least a reasonable one, and there was no evidence to impeach the witness’ good faith in holding it…

Finally, there is evidence that the Times published the advertisement without checking its accuracy against the news stories in the Times’ own files. The mere presence of the stories in the files does not, of course, establish that the Times “knew” the advertisement was false, since the state of mind required for actual malice would have to be brought home to the persons in the Times’ organization having responsibility for the publication of the advertisement. With respect to the failure of those persons to make the check, the record shows that they relied upon their knowledge of the good reputation of many of those whose names were listed as sponsors of the advertisement… We think the evidence against the Times supports, at most, a finding of negligence in failing to discover the misstatements, and is constitutionally insufficient to show the recklessness that is required for a finding of actual malice…

We also think the evidence was constitutionally defective in another respect: it was incapable of supporting the jury’s finding that the allegedly libelous statements were made “of and concerning” respondent …

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama is reversed, and the case is remanded to that court for further proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.

JUSTICE BLACK, with whom JUSTICE DOUGLAS joins, concurring.

I base my vote to reverse on the belief that the First and Fourteenth Amendments not merely “delimit” a State’s power to award damages to “public officials against critics of their official conduct,” but completely prohibit a State from exercising such a power. The Court goes on to hold that a State can subject such critics to damages if “actual malice” can be proved against them. “Malice,” even as defined by the Court, is an elusive, abstract concept, hard to prove and hard to disprove… Unlike the Court, therefore, I vote to reverse exclusively on the ground that the Times and the individual defendants had an absolute, unconditional constitutional right to publish in the Times advertisement their criticisms of the Montgomery agencies and officials…

The half-million-dollar verdict does give dramatic proof, however, that state libel laws threaten the very existence of an American press virile enough to publish unpopular views on public affairs and bold enough to criticize the conduct of public officials. The factual background of this case emphasizes the imminence and enormity of that threat. One of the acute and highly emotional issues in this country arises out of efforts of many people, even including some public officials, to continue state-commanded segregation of races in the public schools and other public places despite our several holdings that such a state practice is forbidden by the Fourteenth Amendment. Montgomery is one of the localities in which widespread hostility to desegregation has been manifested. This hostility has sometimes extended itself to persons who favor desegregation, particularly to so-called “outside agitators,” a term which can be made to fit papers like the Times, which is published in New York. The scarcity of testimony to show that Commissioner Sullivan suffered any actual damages at all suggests that these feelings of hostility had at least as much to do with rendition of this half-million-dollar verdict as did an appraisal of damages. Viewed realistically, this record lends support to an inference that, instead of being damaged, Commissioner Sullivan’s political, social, and financial prestige has likely been enhanced by the Times’ publication. Moreover, a second half-million-dollar libel verdict against the Times based on the same advertisement has already been awarded to another Commissioner. There, a jury again gave the full amount claimed. There is no reason to believe that there are not more such huge verdicts lurking just around the corner for the Times or any other newspaper or broadcaster which might dare to criticize public officials. In fact, briefs before us show that, in Alabama, there are now pending eleven libel suits by local and state officials against the Times seeking $5,600,000, and five such suits against the Columbia Broadcasting System seeking $1,700,000. Moreover, this technique for harassing and punishing a free press — now that it has been shown to be possible — is by no means limited to cases with racial overtones; it can be used in other fields where public feelings may make, local as well as out-of-state, newspapers easy prey for libel verdict seekers.

In my opinion, the Federal Constitution has dealt with this deadly danger to the press in the only way possible without leaving the free press open to destruction — by granting the press an absolute immunity for criticism of the way public officials do their public duty…

An unconditional right to say what one pleases about public affairs is what I consider to be the minimum guarantee of the First Amendment.

I regret that the Court has stopped short of this holding indispensable to preserve our free press from destruction.

JUSTICE GOLDBERG, with whom JUSTICE DOUGLAS joins, concurring in the result.

… In my view, the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution afford to the citizen and to the press an absolute, unconditional privilege to criticize official conduct despite the harm which may flow from excesses and abuses. The prized American right “to speak one’s mind,” about public officials and affairs needs “breathing space to survive.” The right should not depend upon a probing by the jury of the motivation of the citizen or press. The theory of our Constitution is that every citizen may speak his mind and every newspaper express its view on matters of public concern, and may not be barred from speaking or publishing because those in control of government think that what is said or written is unwise, unfair, false, or malicious. In a democratic society, one who assumes to act for the citizens in an executive, legislative, or judicial capacity must expect that his official acts will be commented upon and criticized. Such criticism cannot, in my opinion, be muzzled or deterred by the courts at the instance of public officials under the label of libel…

It may be urged that deliberately and maliciously false statements have no conceivable value as free speech. That argument, however, is not responsive to the real issue presented by this case, which is whether that freedom of speech which all agree is constitutionally protected can be effectively safeguarded by a rule allowing the imposition of liability upon a jury’s evaluation of the speaker’s state of mind. If individual citizens may be held liable in damages for strong words, which a jury finds false and maliciously motivated, there can be little doubt that public debate and advocacy will be constrained. And if newspapers, publishing advertisements dealing with public issues, thereby risk liability, there can also be little doubt that the ability of minority groups to secure publication of their views on public affairs and to seek support for their causes will be greatly diminished…

To impose liability for critical, albeit erroneous or even malicious, comments on official conduct would effectively resurrect “the obsolete doctrine that the governed must not criticize their governors.” …

This is not to say that the Constitution protects defamatory statements directed against the private conduct of a public official or private citizen. Freedom of press and of speech insures that government will respond to the will of the people, and that changes may be obtained by peaceful means. Purely private defamation has little to do with the political ends of a self-governing society. The imposition of liability for private defamation does not abridge the freedom of public speech or any other freedom protected by the First Amendment…

Questions

1. Actual malice is a difficult test to meet, given that you normally need evidence of the defendant’s state of mind to establish that they knew they were lying or were acting recklessly. While much more protective of the media than other standards, some critics argue that it creates a toxic climate that discourages many otherwise qualified people from entering public life. Do you think the Court has struck the correct balance here?

2. Why do you think Black and Goldberg call for an absolute privilege for speech about public affairs or about public officials—that is, preventing defamation lawsuits in this way? Search for the definition of a “SLAPP” lawsuit online. How might Black and Goldberg’s standards prevent this?

3. How—if at all—does the rise of social media alter your assessment of these rules?

Sullivan was a transformative decision, immediately impacting the defamation law of multiple states. Unsurprisingly, it also drew a good deal of criticism. Some critics objected, on federalism grounds, that the Court had unjustifiably intruded on what had previously been an issue of state law. Others felt the decision did not sufficiently consider the harms that public officials could face, requiring them to run a gauntlet of false attacks as the price for entering political life.

Still other critics, echoing the concurring opinions, worried that the actual malice requirement would not achieve the ends it sought. Rich and powerful plaintiffs, the fear went, could still drag defendants into court, costing them time and money even for a case they were almost certain to win. The legal process itself could discourage media from criticizing public figures, regardless of whether damages were likely.