6 Heroes & Deus Ex Machina

In “Post-Climapocalyptic Dystopias,” we explored films that had at their heart an “antihero.” These are characters that “may lack conventional heroic qualities and attributes, such as idealism, courage, and morality. Although antiheroes may sometimes perform actions that most of the audience considers morally correct, their reasons for doing so may not align with the audience’s morality.”[1] These characters redeem themselves, to some extent, in the end, even though they may remain flawed. In Waterworld, for example, The Mariner begins as a man concerned only with his own survival but along his journey finds himself compelled to protect, and even care for, others (although in the end he does decide to, we assume, return to his loner existence). Although we don’t learn a lot about Max before the events of Fury Road, we do understand, based on his initial reaction to Furiosa and the other women, that his first instinct is self-preservation, but like The Mariner he comes to find himself allied with the women in their shared journey of survival. And Furiosa can be viewed as an antihero as well, having been in the service of Immortan Joe prior to her rebellion against him. Personally, I find antiheroes to be some of the most interesting characters in cinematic history.

in 2009 in Syracuse, Italy; the sun god sends a

golden chariot to rescue Medea. Licensed by

I, Sailko under CC BY 2.5.

But it seems inevitable that eventually a solution to the problems presented by climate change in film would be the true hero, with the attendant characteristics of idealism, courage, and morality. In the 2010s, a series of films appeared that depicted heroes saving the world. These most often depict a world ravaged by the effects of climate change, about which they can do nothing without the intervention of heroes or even superheroes. It is no coincidence that most of these also were box-office blockbusters. Additionally, creators of these films sometimes relied on a “Deus Ex Machina” ending, which is a structural convention dating back to ancient Greece that literally means “god from the machine.” Often contrived, the plot device entailed the sudden appearance of one or more gods, who ascended from on high in a chariot or other “machine,” to intervene in, and resolve, the problems of human (also somewhat common in Shakespeare’s plays).

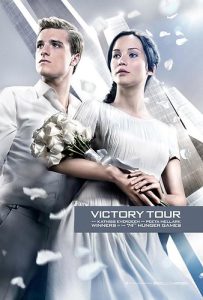

Few young adult novels have captured the post-climapocalyptic dystopia as imaginatively and horrifyingly as The Hunger Games series, by Suzanne Collins. In 2012, the first book in the series was adapted for the screen. In it, the global warming that brought about societal collapse that created the totalitarian regime of Panem is nearly forgotten history. Panem (formerly North America) is divided into 12 Districts, and each year a boy and a girl from each are selected as “tributes” and forced to compete in the Hunger Games, an elaborate televised fight to the death. When her younger sister is selected as tribute, Katniss Everdeen (Jennifer Lawrence) volunteers to take her place – cementing her status early as a hero, willing to sacrifice herself for others, in the series. With her district’s male tribute, Peeta Mellark (Josh Hutcherson), Katniss travels to the Capitol to train and compete in the Hunger Games.

Her survival (and Peeta’s) at the end of the film, however, is short-lived. The subsequent three films in the series show her evolving into, albeit reluctantly and largely symbolically at first, the leader of the rebellion: the “Mockingjay.” The rebellion leads to the eventual death of Katniss’s arch nemesis, President Snow (Donald Sutherland), the installation of a new, more benevolent President, and the end of the games.

The Hunger Games is the twenty-first highest-grossing film franchise of all time – and the first entry in the “Cli-Fi Film Franchise.” The next was a sleeper hit: Kingsman: The Secret Service (2014), directed by Matthew Vaughn – another personal favorite that was quite a surprise when I saw it originally. In the film, eco-terrorist Richmond Valentine (Samuel L. Jackson) seeks to address climate change by – reminiscent of Klaatu in The Day the Earth Stood Still – saving the earth from humans and wiping out most of humanity. He is eventually thwarted by members of the Kingsman – an elite British intelligence service named for the tailor shop in Savile Row used as a front for their operations – including veteran Kingsman Harry Hart (Colin Firth) and rookie, legacy recruit Gary “Eggsy” Unwin’s (Taron Egerton). Popular at the box office, the film received mixed reviews but spawned two sequels, Kingsman: The Golden Circle (2017) and The King’s Man (2021), and a fourth film in the franchise is apparently in the works.

Even more popular has proven the Marvel Cinematic Universe, a twenty-film franchise beginning in 2008 based on classic heroes from the comic books. The character Thanos, lurking in the background in several of those films, comes to the fore in Avengers: Infinity War (2018). With motives somewhat similar to Richmond Valentine’s and Klaatu’s, Thanos (Josh Brolin) fears the destruction of limited resources in the universe by its inhabitants and seeks to restrict population growth and eliminate half of all life by “restoring balance” one planet at a time. He believes he can do this using the “Infinity Stones,” six gems created when different cosmic forces were crystalized during the Big Bang. Infinity War follows Thanos across planets as he battles different groups of Avengers to take possession of all six stones. His success at the climax of this film led to an ending that was shocking and even controversial to many Marvel fans, sparking a huge wave of social media commentary and backlash (I will leave it to you to watch the film to find out why). In its sequel, Avengers: Endgame (2019) – and the related Spiderman: Far from Home in the same year – the members of the Avengers and their allies attempt to reverse Thanos’s shocking actions.

The benefit of these movies featuring heroes in the “classic,” ancient Greek or comic book vein (often as instruments of “Deus Ex Machina”) is their popularity and reach; however, they offer fairly unrealistic solutions for the problems of human-caused climate change. More nuanced, sustainable solutions that do not rely on the hope that no other bad actors, like Snow, Valentine, or Thanos, will appear and require similar heroic actions are needed. In the next module, the films address climate change through more complex, internal, psychological means – but we’ll see whether or not they offer more potentially viable solutions.

KNOWLEDGE CHECK

Video

- Antihero. Wikipedia. Retrieved February 24, 2023. ↵